The Architect in Society

The role of the architect has evolved over centuries to cover an expanding array of tasks and responsibilities. Today the core role of the architect is usually that of the primary professional design service provider, coordinating the various stakeholders during the planning, design, and construction process of buildings. Technological and sociological changes, as well as increasing globalization, continue to affect the way architecture is practised. Architects continue to shape our built environment, as their training experience and regulated status allow them to design buildings of all types. Their work has a major impact on human activity and the planet; hence, they have a tremendous responsibility towards fellow citizens and the environment. Architects add value to the built environment; their primary contribution and impact are its design, as well as their ability to coordinate and oversee projects to completion within schedules and budgets.

The Evolving Role of the Architect

Challenges and Opportunities for Architects in the 21st Century

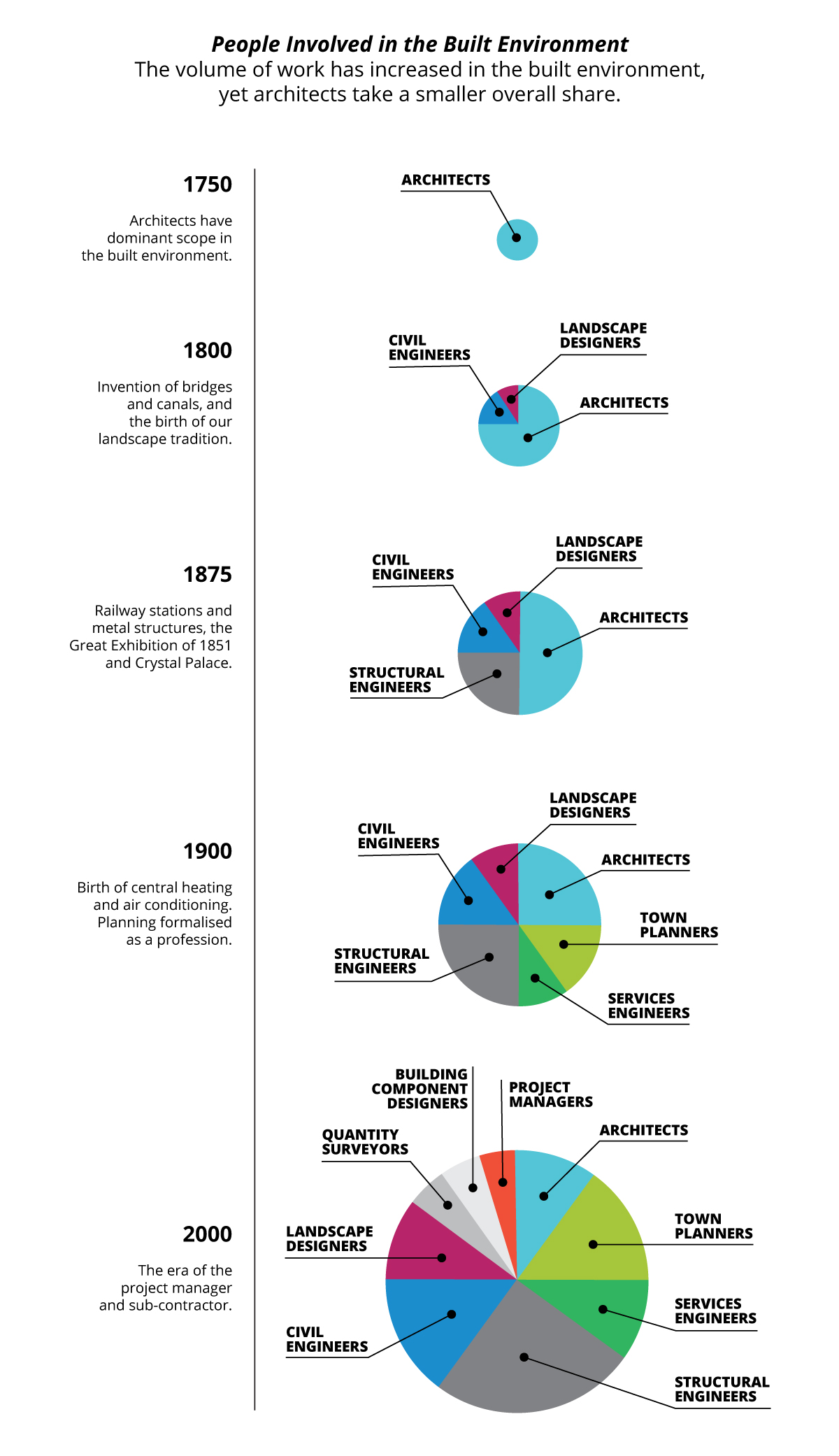

Traditionally, an architect was considered to be a professional with general knowledge of the many disciplines involved in the design, construction, maintenance and alteration of buildings. Over time, technological advancement, population redistribution, and the growth of cities have both physically changed the built environment and changed expectations for the built environment. Architects’ responsibilities have also changed as more and different disciplines introduced into the design-construction-operation supply chain are required. The architect’s role in society has evolved with these changes and continues to evolve.

Today, an architect must have the skills necessary to synthesize, integrate and coordinate various parts of a project into a composite whole. This is not only to satisfy functional and safety requirements, but also to contribute to an orderly, visually pleasing, and sustainable environment. As architects are increasingly being asked more specific questions with regards to specific subjects, there is a growing trend to specialize to meet complex issues, requirements or contexts. Areas of specialization may include aspects of planning and programming, building regulations, design, production, management, sustainability, site supervision or construction. The individual architect may thus become an expert in a specific building type, or accredited or certified in specialties such as building code, building envelope, project management, sustainable design, or heritage conservation. However, maintaining a general expertise in all aspects of the profession remains a foundation of keeping architecture healthy and enhances the credibility of the profession in the eyes of the public. The architect also maintains an ethical responsibility for passing along their knowledge and skills, through teaching, mentoring, and hiring and training the next generation of architects.

The practice of architecture is interrelated with many other design disciplines, including various types of engineering, landscape design, sociological and planning studies, and public art. In the complex task of coordinating the many specialists involved in a project, the architect develops a unique role and set of skills. A holistic view of the built environment has enabled architects to undertake a variety of strategic roles in society. These roles include acting as facilitators, collaborators, and communicators in addressing the needs of an increasing number of stakeholders, voicing their views and desires on how the built environment should be shaped and the impact it has at local and global scales.

The growth of existing areas of architectural practice and new frontiers provide exciting opportunities for architects, including:

- strategic planning and facility programming at pre-design stages;

- inclusive design;

- sustainable design;

- existing buildings (maintenance, life and fire safety upgrades, reuse, repurposing, heritage conservation);

- urban design and renewal;

- new forms of project delivery, such as integrated design processes;

- new technologies and communication tools;

- globalized practice.

Strategic Planning and Facility Programming at Pre-Design Stages

Institutional and infrastructure projects are becoming larger and more complex due to the number of stakeholders involved, and their duration now often extends for several years with phased implementation and construction. The architect can assist with the general planning of such undertakings and/or the detailed programming of a facility.

Inclusive Design

The Inclusive Design Research Centre defines inclusive design as:

“design that considers the full range of human diversity with respect to ability, language, culture, gender, age and other forms of human difference.”

Inclusive Design Research Centre - OCAD University

Historically, accessibility has been limited to accommodating persons with disabilities. Inclusive design extends the concept of accessibility to address everyone’s needs with respect to equity, functionality, safety, gender, culture and religion. The architect should be an ambassador for inclusive design so that the specific needs, values and concerns of a diverse society are reflected and integrated in its buildings. Inclusive design embraces the reality that people who use buildings come from a variety of cultural backgrounds, are dimensionally different, and present a wide range of physical and sensory abilities. Recognition of such diversity will result in building designs accommodating the widest range of inclusion.

Emerging trends in inclusive design include recognizing that wheelchairs and other mobility devices are as diverse as the people who use them and that they require more space than is usually specified in codes and standards; buildings can be designed to better accommodate persons with vision loss, as well as those with hidden disabilities such as strength or stamina limitations; and an equivalent level of life safety should be available to everyone in a building in an emergency situation.

Sustainable Development

Buildings are society’s response to population growth, urbanization and the economics of land use development in addition to the age-old function of meeting humans’ basic need for shelter. The conventional construction and operation of buildings produce greenhouse gas emissions. Buildings are contributors to climate change. Because of that contribution, architects have an opportunity as well as a responsibility to adjust their practice so that the buildings they design do not, for example:

- contribute to the heat island effect and the attendant heat stress illnesses in urban populations;

- destroy habitat for local flora and fauna;

- increase peak storm water flows and contribute to urban flooding;

- unnecessarily deplete natural resources, including potable water;

- become quickly unlivable in power outages, summer or winter.

There are multiple views about what classifies as sustainable development. With interest in this area increasing at an exponential rate, and with multiple certifications for “green” building available to the building owner, a shared working definition is important to promote communication and understanding. The United Nations defines sustainable development:

“Sustainable development has been defined as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

Building enclosures and mechanical and electrical systems have unusually long service lives compared to other material goods. This means that the ability to mitigate poor performance of an existing building arises infrequently and may only be present every second human generation. This “lock-in” of wasteful performance and resulting greenhouse gas emissions or other environmental disruption may give cause for clients or the general public to demand better building performance than conventional methods provide.

The attention of the architect’s client to these matters is the key to the architect’s ability to implement climate change adaptation or mitigation measures. Many adaptation or mitigation measures are “no regrets” actions that do not involve a construction premium and therefore can be incorporated into design practice in a way that does not require the client’s direct attention. However, there are many other conditions in the interlinked systems of land use planning, transportation planning and access, development finance, and property development that require discussion with the client in the pre-design stages of a project.

It has long been known that the annual energy expended (and emissions generated) by commuters going to and from an office building can be larger than the annual energy consumption of the building itself. Conventional measures to mitigate an unfavourable location are not commonly considered because the building site is a given in the client brief. This default requires a different approach. For example, extra attention to microclimate design may push a project away from generic solutions, but in the process identify and develop latent conditions on an unfavourable site to produce a unique and valuable experience. Matching or adding facility program elements to difficult site conditions is one technique to generate added value for a site. Understanding the potential of a site from a sustainability perspective may also support more effective design solutions from other perspectives, including financing and insurance costs.

Sustainable and regenerative design presents opportunities for innovation and collaborative solutions in both design processes and outcomes. It is difficult to deny that in the years to come a foundational aspect of architectural design success will be the design response to driving factors in both the micro and macro environments.

Revitalizing Existing Buildings

For many architects, working with existing buildings comprises a significant volume of the work, ranging from minor renovations to complete makeovers, either maintaining existing occupancies or converting to new uses. These projects may extend beyond simple renovations to completely revitalize the existing building’s aesthetic and performance. Existing buildings in this context include all existing buildings, even those considered heritage (over 40 years old) but not designated as such. An existing building may not be designated, but may still be architecturally and culturally significant, necessitating care in how change is effected on the building. This presents a challenge of making function follow form, and must also consider the impact to the building design, building structure, envelope, environment and fit with the local community. With the growing need to make buildings more energy efficient and sustainable (to reduce greenhouse gases (GHGs) and capitalize on existing infrastructure and embodied energy), understanding the existing building’s technologies, past uses, and performance will inform how the building may be renovated to achieve the best balance between performance, durability, sustainability goals and satisfaction of local community interests.

An architect may undertake all aspects of the project within his or her practice, but often other specialists beyond the core disciplines of structural, mechanical and electrical will be needed to provide additional depth, and may include: cultural experts, heritage professionals, and building historians, as well as professionals with expertise in building envelope, building materials, sustainability, environment, energy modeling, building controls, building commissioning, fire protection, etc.

Urban Design and Renewal

Architects are often engaged to complete master planning studies and intensification studies, as well as other investigations into the development and/or renewal potential of properties both urban and rural. Contributing their knowledge of architectural design and implementation, and the unique spatial requirements of specific building forms and typologies, an architect’s involvement in urban design lends credibility to the physical suitability and practical feasibility of new built fabric. Architects are also trained to consider context and frontage relationships with surrounding streets, and public space resources. Furthermore, architects can provide specific advice and expertise pertaining to the renewal potential of existing buildings and structures within a larger urban framework. Being familiar with coordinating the inputs of a range of sub-consultant disciplines, architects are of great value as leaders of complex, multi-disciplinary design teams often engaged to provide urban design studies. And lastly, as they are often asked to interpret urban design guidelines in the detailed design of individual works of architecture, architects can contribute meaningfully to the authorship of urban design guidelines and other documents that seek to influence the design of our cities.

New Forms of Project Delivery

Clients and governments are constantly seeking new or varied forms of project delivery that may result in alternate forms of financing and more efficient building design and construction methods. In the face of global warming and in order to reduce energy consumption, a much higher level of building energy performance is required. This has resulted in new and evolving methods of project delivery.

New forms of project delivery result in changes to the architect’s professional relationship with clients, users and others in the construction industry. Project delivery methods such as design-build and public-private partnerships (P3s) result in the architect being engaged by a builder or a financial entity and not directly by the owner or users of the building. Other project delivery methods such as integrated project delivery can demand greater cost efficiency, and shorter timeframes for document production. This leads to the potential for increased risk and liability for the architect, therefore challenging the architect and project stakeholders to balance the risks and rewards of the changing project delivery landscape. Project delivery is evolving and architects must adapt, taking into consideration their liability in delivering services while always considering the public interest.

On the other hand, architects can play a key role in integrated design processes by skillfully addressing the various needs and objectives of multiple stakeholders, including multi-party client groups, the other professionals and experts on the design team, and the larger community. The integrated project delivery method results in changed relationships between the architect and other project stakeholders, including the owner, builder and design team. It may prompt the architect to adopt a new business model. These varied project delivery methods therefore present challenges for the practice of architecture, but also offer opportunities, including new roles such as integrators, compliance architect, or advocate architect.

See also Chapter 4.1 – Types of Design-Construction Program Delivery.

New Technologies, Communication Tools, and Processes

BIM, automation and advanced visualization are some of the technological innovations that have continued to transform architectural practice. The acronym BIM refers to both building information management and building information modeling, depending on the context and the focus of the author of a particular publication. Modeling and simulation software programs to assist architects in the analysis of lighting or thermal resistance, in the creation of three-dimensional images, or in the preparation of more accurate cost estimates have become widespread. Some of them are even accessible to anyone now, therefore increasing both the client’s requirements and expectations. Some firms who do not have access to these new technologies may outsource parts of their work. The historical role of the architect to gather, process and synthesize information, and to use presentation techniques to communicate a solution, is more and more influenced by the choice of new format options.

BIM is becoming more widespread as a tool for integrated building design and as a communication tool for coordination with consultants, constructors, and component fabricators. Some public sector organizations now require that projects be delivered using BIM.

BIM requires not only changes in a firm’s technology, but, more importantly, changes in business, operational, and project processes. The integration of design processes across the design-construction-operation supply chain requires rethinking contractual relationships, organizational culture, and a redistribution of effort with a firm.

See Chapter 5.6 – Building Information Managing for a discussion of these topics.

Globalized Practice

Architectural practices vary in size from sole practitioners to large corporations. The range of projects undertaken by practices also varies greatly. The profession includes firms with multiple offices, country-wide and internationally. Projects may be executed through multinational resource pools, or through joint-venture arrangements.

Smaller firms may form joint ventures to combine specific strengths in order to bid on larger contracts or projects requiring specific expertise. Such collaboration may be established for a sole project or put in place over longer periods on a variety of endeavours. This globalization presents new challenges to architects to adapt to different practices, cultures, political environments, regulations, building construction standards, workers’ safety codes and new markets, as well as to cope with increased competition in the Canadian market from both local and international firms.

Types of Practice or Professional Activity

Architects work in a variety of professional contexts. These include:

- private practice;

- corporations (private sector);

- government and institutions (public sector);

- education and research;

- construction and development;

- non-governmental organizations;

- formal design review panels;

- independent expert witness.

Architects may also work in a combination of these situations providing that the architect is not in a conflict of interest.

Professional Responsibility

The architect’s responsibility extends beyond the client to fellow professionals, the profession, and society in general. The amount of responsibility an architect is prepared to accept will determine how they practise architecture. The employed or salaried architect has reduced direct responsibility to his employer’s client, whereas the sole practitioner carries the entire responsibility. Architects in partnership share this responsibility. The architect’s responsibility varies depending on their role(s).

See also Chapter 1.3 – Professional Conduct and Ethics for more information on professional obligations and responsibilities.

Architects in Private Practice

“Architectural practice is the setting where ethos and circumstances lock horns, where individual and professional goals combine with budgets, deadlines, skills, organization, power, context and regulations.”

Cuff

Architects employed by a private practice may be:

- employed (salaried) architects working for other professionals;

- independent contractors providing services to other architects;

- specialist consultants in various fields, such as project management, building code, building envelope, sustainable design, conservation, and specifications.

Self-employed architects may be:

- sole proprietors;

- in partnership with other architects or engineers;

- directors or shareholders of an architectural corporation.

Self-employed architects in private practice must maintain expertise in two distinct areas:

- the performance of architectural services;

- the operation and management of a practice, including staff.

See also Chapter 3.1 – Starting and Organizing of an Architectural Practice.

The architect in private practice accepts liability for the architectural commissions which the architect undertakes.

See also Chapter 3.6 – Human Resources for a discussion of employees and independent contractors in the design professions.

Architects Employed in a Corporation other than an Architectural Practice (Private Sector)

Many corporations that do not practise architecture employ architects as members of their staff. For example, many large corporations employ architects in their real estate, design, construction, and facilities management divisions. The architect working for a corporation must nevertheless comply with the provincial or territorial requirements for practice and the use of the professional seal. Some of these architects may provide a full range of professional services for their employer, the corporation. Alternatively, they may simply manage the design and construction by selecting architects and consultants, and by coordinating the provision of architectural services as a representative of the corporation.

Frequently, corporate architects provide services in:

- site selection;

- project planning;

- programming;

- consultant selection;

- contract negotiations;

- construction contract administration;

- facilities management and maintenance.

Architects in Government and Institutions (Public Sector)

The architect can also serve society as a civil servant, that is, as an employee of the government, either at the federal, provincial/territorial or municipal level, or for a public institution. Public sector employees are not generally required to purchase a professional insurance, but they are nonetheless fully accountable and personally liable for their work.

Often, universities and hospitals require in-house expertise for the management and expansion of their buildings and physical assets. Architects in government and institutions can exert influence and develop policies related to the built environment. Opportunities within the public sector may include positions at a technical, managerial or policy level. All levels of government construct and fund building projects as well as regulate the built environment.

Architects can play a variety of roles within government. Architects in these roles may require an advanced skill set in stakeholder management and engagement, negotiation, and interpersonal relationship building. Communication skills become paramount when dealing with a wide range of stakeholders, such as the general public, government officials, other architects, developers’ contractors, other branches within their department, civil servants in other departments or jurisdictions, deputy ministers, Treasury Board representatives, politicians and the media.

Because many decisions regarding the built environment are made in the political arena, some architects choose to run for office for:

- various levels of government;

- school boards;

- professional or business associations.

Architects employed in government and institutions may be required to maintain “professional” registration with a provincial or territorial association of architects. In addition to working in a different context, the lapse or absence of a professional license can create a distance between the government “professional” and fellow architects and can lead to a lack of currency and knowledge of the profession. Conversely, the lack of familiarity with government operations from architects in private practice may lead to misunderstandings when delivering services in this context.

Federal

At the federal level, architects work as:

- employees of Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC), Department of National Defence (DND), Defence Construction Canada (DCC), and several other federal government departments;

- conservation architects within the Federal Heritage Building Review Office (FHBRO) and Parks Canada Agency, the guardians of national historic sites and buildings;

- researchers within federal government agencies such as the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) and the Institute for Research in Construction (IRC) of the National Research Council (NRC);

- technical representatives and policy developers or other officials related to the built environment and building codes.

Provincial/Territorial

At the provincial/territorial level, architects work as:

- employees of various provincial/territorial government ministries, crown corporations, and agencies related to the built environment (for example, education, public works and government services, housing, planning, tourism, health, building codes and regulations, culture and heritage);

- researchers and technicians;

- policy developers for the provincial/territorial government.

Municipal

At the municipal level, architects may work as:

- building inspectors and plans examiners;

- administrators and designers within municipal departments of planning and development, specializing in areas such as land-use planning and zoning, urban design, and heritage conservation.

Architects in Education and Research

Architects may pursue a career in academia as faculty members at the university schools of architecture, the community college schools of design and construction, or as researchers in a variety of settings. The university schools of architecture in Canada have faculty on a full-time, visiting or adjunct (part-time) basis. See also “List: Canadian University Schools of Architecture with Accredited Programs” in Chapter 1.5 – Admission to the Profession.

Some architects who teach also undertake research. Many architects also teach at the various community colleges, technical institutions, and cégeps (collèges d’enseignement général et professionnel in Québec), which train architectural technicians, technologists, and other students who study design and the construction industry. Practising architects may also be invited as mentors, tutors and/or jurors by architectural schools to comment and help students with their projects (critiques).

Architects may be involved in both pure and applied research. Opportunities exist in various government agencies and universities, and with manufacturers of building products and certain specialized institutes of research.

Architects in Construction and Development

Increasingly, those with architectural training are selecting careers directly in the construction industry or in real estate development. As designers, planners and managers, they can contribute significant skills to this sector of the economy. Typical careers include:

- developer;

- construction manager;

- contractor;

- design-builder;

- real estate agent.

Many developers have their own in-house staff to plan and coordinate consultants in the provision of design services for projects, and many building contractors are involved in design-build work, employing architects directly. The following skill sets can be especially marketable to builders and developers:

- marketing;

- economic feasibility studies;

- conceptual problem-solving;

- design;

- building code compliance;

- construction planning;

- estimating and review of project budgets;

- construction contract administration.

Architects sometimes lead the development and building process; in fact, the number of architect-led design- build firms, particularly in the United States, is growing.

Architects must confirm with the provincial or territorial associations of architects that their services and roles within a design-build firm comply with provincial or territorial regulations.

Architects in Non-Governmental Organizations

Architects may work for non-governmental organizations (NGO) involved in emergency relief, cooperation and development (ex.: Architecture Sans Frontières), as well as advocacy groups related to, among others, professional practice (ex.: Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC), provincial or territorial associations of architects), sustainable design (ex.: Green Building Council, BREEAM, Passive House), or heritage conservation (ex.: ICOMOS, APTi, National Trust for Canada, Ontario Heritage Trust, Heritage Toronto, Action patrimoine, Héritage Montréal, Association québécoise pour le patrimoine industriel (AQPI), etc.).

Architects involved in these organizations may develop new regulations, policies, frameworks, best practices, or new design guidelines coming from various sources (health, environmental sensitivities, legal, research), as well as training courses, public awareness programs and site visits. These activities provide opportunities for sharing knowledge and experience, shaping the profession, networking, and having a positive impact in society.

Architects in Formal Design Review Panels

Architects may be involved in a formal role in various public design review panels or advisory committees on city planning and heritage conservation. Similarly, architects may be invited to act as jurors for architectural competitions or awards (ex.: Governor General’s Medals in Architecture, Canadian Architect Awards of Excellence, award programs led by provincial or territorial associations of architects).

Architects as Independent Expert Witness

Architects may also function in a capacity of expert witness in situations where building or project failure has resulted in mediation, arbitration or litigation. The increasing complexity of building technologies, rising expectations on the part of many stakeholders in the design/construction/operation industries, and growing attitudes toward risk aversion and transfer have resulted in opportunities for architects with specialized skills to provide clarity in dispute resolution processes.

See also Chapter 3.10 – Other Services Provided by an Architect, Appendix A – Architect as Expert Witness for a detailed description of this scope of practice.

Other Roles for Architects

An architectural education is often valuable for other fields of endeavour. Architects look beyond architecture for careers related to design, planning, and construction, and as specialist consultants. New career opportunities are also available to architects willing to pursue studies in related professions and become specialists with a multi-discipline background. Some examples include:

- architect/engineer;

- architect/planner/urban designer;

- architect/lawyer;

- architect/business administrator;

- architect/facilities planner;

- computational designer;

- data specialist;

- digital practice information manager;

- BIM model manager;

- integration manager;

- sustainability consultant;

- energy modeler;

- client representative or project manager;

- designer of virtual environments for computers;

- mediator/arbitrator;

- forensic investigator.

Refer to the RAIC website’s Becoming an Architect for a list of some of the non-traditional jobs for architects (https://raic.org/raic/becoming-architect).

References

Cuff, Dana. Architecture: The Story of Practice. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 1991.

Lewis, Roger K. Architect? A Candid Guide to the Profession. Revised Edition, Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 1998.

“Livre blanc pour une politique québécoise de l’architecture.” Ordre des architectes du Québec, March 2019, www.oaq.com/fileadmin/Fichiers/Publications_OAQ/Memoires_Prises_position/LIV-PQA-20180410.pdf.

“Référentiel de compétences lié à l’exercice de la profession d’architecte au Québec.” Ordre des architectes du Québec 2017, https://www.oaq.com/fileadmin/user_upload/OAQ_RCOMP_2018_VFINALE.pdf, accessed April 20, 2020.

“What Is Inclusive Design.” Inclusive Design Research Centre – OCAD University, https://idrc.ocadu.ca/about- the-idrc/49-resources/online-resources/articles-and-papers/443-whatisinclusivedesign, accessed April 20, 2020.

Royal Institute of British Architects. Guide to Using the RIBA Plan of Work 2013, London: RIBA Publishing, 2013.

“Toolkit for Building Projects: From Concept to Construction.” Northwest Territories Association of Architects, 2014, http://nwtaa.ca/data/uploads/NWTAA_Toolkit-for-Building-Projects_WEB.pdf, accessed September 11, 2020.

Farrell, Terry. “The Farrell Review of Architecture and the Built Environment.” The Farrell Review, 2017, www.farrellreview.co.uk/download, accessed April 15, 2020.