Definitions

Construction Manager: An individual or company employed to oversee and direct the construction elements of a project, usually the whole of the construction elements and the parties who are to perform them; a company that contracts with an owner to perform such services for a fee.

Design-Build: Method of project delivery in which one business entity or alliance (design-builder) forges a single contract with the owner, and undertakes to provide both the professional design services (architectural/engineering) and the construction.

Program: The term “program” has several meanings in architectural practice. In the context of program and project management, a program is “a group of related projects managed in a coordinated way to obtain benefits and control not available from managing them individually.” (Weaver, 2010)

Project: A project is “a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique project service or result.” (Weaver, 2010) The design of a building is a project. The construction of a building is another, different project.

Project Manager: The term project manager has become widely used to describe the person responsible for managing a project’s scope, schedule, cost, quality and resources. However, there are many different firms and companies involved in any design-construction project and the person in charge of the project within their respective company may be called a project manager.

In the context of this chapter, the project manager is the individual assigned the responsibility to manage the design-construction project on behalf of the owner. The project architect and general contractor or construction manager report to the project manager. The project manager may be an employee of the owner’s organization, an individual contracted for the project, or an employee of a project management service provider (PMSP) firm. However, the project manager is typically not the owner’s representative, also called the project sponsor. Unlike the owner’s representative, the project manager does not own the project’s outcome.

The term project manager may be confused with construction manager; the meaning has become blurred and is currently often used merely for the individual within the conventional hierarchy (see above).

Preamble

Throughout this handbook, the term “design-construction program” is used to describe the total endeavour of creating a new or renovated facility. At a minimum, this involves a design project and a construction project. These two projects, managed in harmony, constitute a design-construction program. This distinction is important as the architect is responsible for the management of the design project while the constructor is responsible for the management of the construction project. The general public as well as the architectural profession assumes that the architect protects the public interest during both design and construction.

In a complex undertaking, such as a hospital, airport or multi-use community centre, there can be additional distinct projects managed by professionals of other disciplines. These may include a land acquisition and consolidation project, a site analysis project, or a functional programming project. All these projects together, managed by their respective project manager, project architect or project engineer, form a design-construction program.

Typically, the responsibility to fill the role of program manager, the person responsible for the harmonious oversight of the many projects, is that of the client representative. However, this role may be undertaken as an additional service provided by the architect or by a project management service provider firm.

The distinction of program from project, and the further definition of individual projects within the program, form a foundation for understanding the scope of the roles and responsibilities of the architect and differentiating the architect’s responsibilities from those of the client, constructor and others. This understanding then filters to the individual contracts for delivery of design services, building construction, and the other projects needed to realize the complete endeavour.

Introduction

The design and construction industry continues to change. Social, environmental and economic forces have resulted in an evolution of project delivery methods. Multiple project delivery options are available to building owners, and each has its own functions, features, benefits and drawbacks. More than one option is available for each project, depending on the client’s needs and the project team’s ability to deliver. Project delivery methods in the construction industry have evolved in response to:

- increased owner requirements;

- transfer of project risk from the owner to designers and constructors;

- more urgent time frames;

- increased demands for higher building performance and safety;

- the desire to reduce adversarial relationships in construction to achieve higher quality outcomes through collaboration;

- economic pressures.

Project delivery is a general term describing the comprehensive process used to successfully complete the design and construction of buildings and other facilities. The term is used to include all the procedures, actions, sequences of events, obligations, interrelations, contractual relations and various forms of agreement. In this chapter, the traditional term construction project delivery is replaced with design-construction project delivery. The integration of design activities and construction activities has increased over the past decade with innovations in technology, most notably building information modeling (BIM), and innovations in process through integrated project delivery (IPD) and public-private partnerships (P3s).

Although innovative forms of project delivery are becoming mainstream, it must be noted that design activities that may be part of an integrated design-construction team as they relate to the construction, alteration and/or expansion of buildings, are the protected scope of work of architects. No one other than an architect may undertake the practice of architecture beyond the exemptions noted by the provincial acts and regulations. The practice of architecture is a protected scope under legislation, and architects remain responsible for the design, regardless of the other integrated team members and their input.

There is no “best” delivery system; each is appropriate in particular circumstances.

Types of Design-Construction Project Delivery

This section provides:

- a brief description of common delivery methods;

- a basis for comparing them;

- a general evaluation of their advantages and disadvantages.

There are several ways to discuss project delivery methods. They can be discussed in terms of the responsibilities and reporting relationships of the parties in the design-construction endeavour. The functions, features, benefits and drawbacks of each method can be compared. The method can be discussed in terms of each party’s position and influence in the supply chain of design-construction. In program and project management terms, they can be discussed as sets of relationships between projects’ life cycles that make up the total program of design and construction. To provide a comprehensive overview of this critical aspect of architectural service delivery, project delivery methods will be discussed from a variety of views.

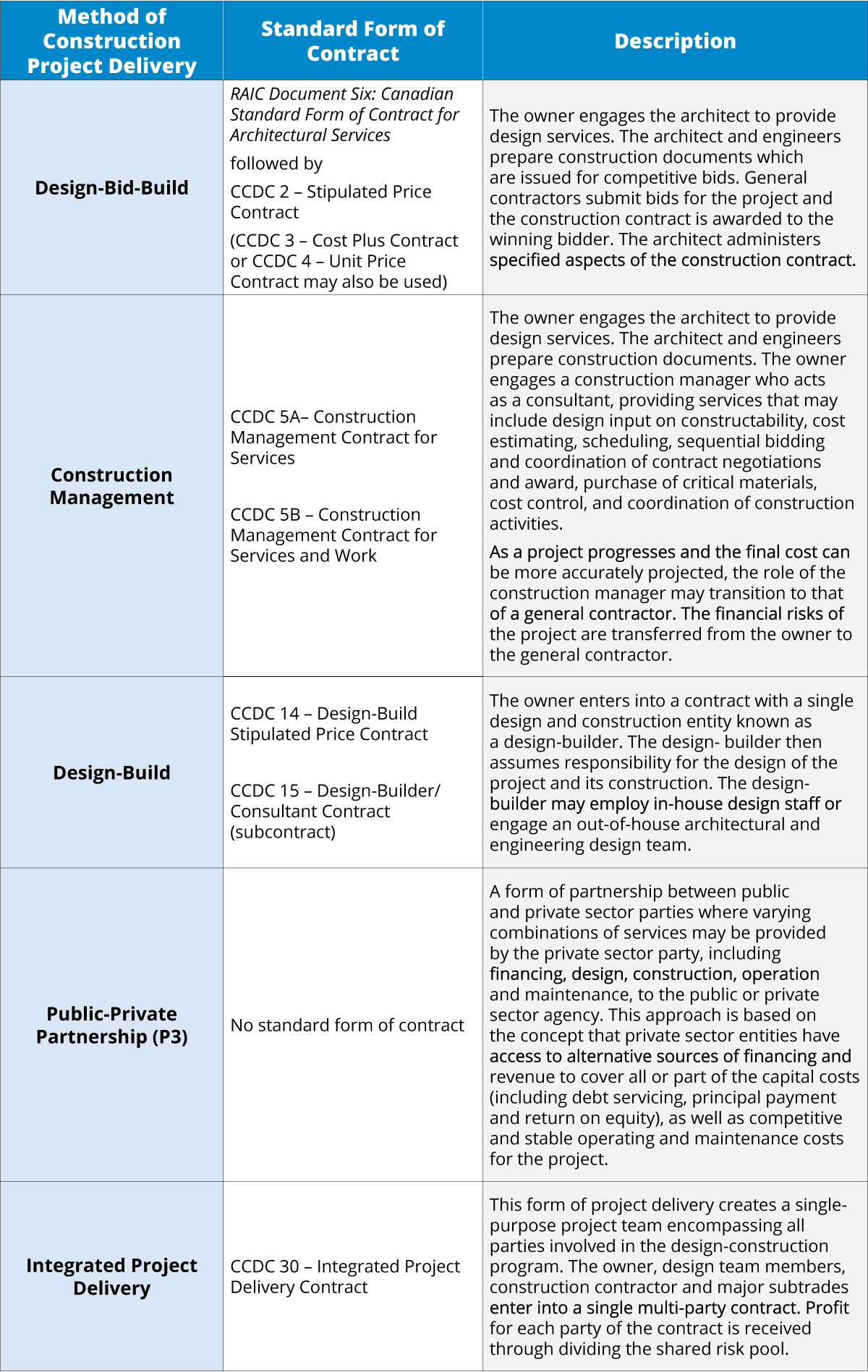

The following table provides a brief executive summary of common types of design-construction program delivery. Note that in all these delivery types, whether retained by the building’s owner directly or retained by a design-builder, the architect holds responsibility for protecting the public interest.

TABLE 1 Comparison of Project Delivery Methods

The Design Project Life Cycle and Project Delivery Methods

One way of exploring different project delivery methods is through comparing the overlap of the life cycle phases of the design project to the construction project. A life cycle is the sequence of phases, from initiation to project closure, that a project goes through to achieve the stated objective. The phases of the design project vary based on the method of project delivery.

The life cycle for the architect of a traditional design-bid-build project generally includes pre-design, schematic design, design development, construction documents, construction contract tendering, construction contract administration and general review, closing/commissioning and post-completion involvement in warranty. The constructor’s project life cycle starts with the tendering phase and ends with completed construction and the warranty period.

Design-build projects change the relationship between the design team and the constructor and move the hiring of the consolidated design and construction team to the beginning of the design-construction program.

Construction management generally includes multiple tendering phases, resulting in overlap of the design project life cycle with the construction project life cycle.

The integrated project delivery (IPD) method has project life cycles not dissimilar to design-bid-build but with different relationships between the project stakeholders.

Program and Project Responsibilities and Project Delivery Methods

Design-Bid-Build or Stipulated Price Construction Contract

Many building projects follow a long-standing method of project delivery often referred to as “design-bid-build,” in which:

- the owner engages an architect to prepare the design, drawings, and specifications;

- the architect engages engineering consultants to complete the design team or the owner engages engineering consultants separately;

- following completion of design documentation, the owner hires a contractor by competitive bidding to build the facility under a stipulated price Contract construction contract (usually CCDC 2);

- the architect administers specified aspects of the construction contract, provides general review of construction works, certifies the payment of the contractor’s invoices, and has legislated and contractual involvements at project completion and during the warranty period.

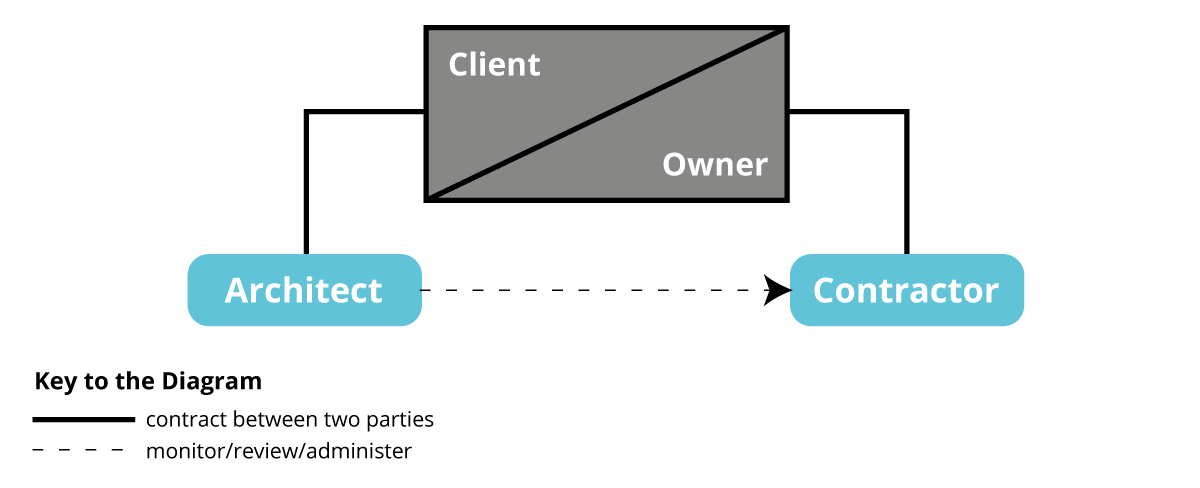

This design-bid-build form of project delivery is characterized by:

- the design project followed by the construction project;

- two independent contracts between the client/owner and architect, and the client/owner and the construction contractor

Figure 1 Design-Bid-Build

Advantages:

- widespread use and familiarity among industry stakeholders;

- thorough resolution of the program requirements and design prior to construction;

- direct professional relationship between the client/building users and the architect;

- clarity of roles and responsibilities assigned to each party;

- price of construction is known before construction begins.

Disadvantages:

- separation of the design project from the construction project, and the designers from the constructor, limits information exchange about construction costs and constructability;

- clients may expect that the project can be completed for the tendered price without inclusion of a construction contingency;

- the contractor is unknown at the time of construction document production;

- contracts, particularly for public sector projects, are awarded to the low bidder who may not be well-qualified to do the work (pre-qualification of contractors on public sector bids may not be permitted by policy or regulations).

Construction Management

Construction management is a broad term covering a variety of project delivery scenarios in which the design team is augmented with the addition of a construction manager (CM) at an early stage to advise on and oversee such elements as schedule, cost, construction method or building technology. A construction manager may be:

- an architect;

- a contractor;

- an engineer;

- a developer;

- an individual or team with specialized training in construction management.

Because this method adds a construction management consultant and the associated fee, it is more commonly used when:

- projects may be large and complex;

- time is of the essence as construction can commence prior to completion of design documentation;

- change of requirements and/or design is anticipated and rapid response is needed;

- general contractors are not prepared to assume the financial risk associated with a stipulated price contract.

Occasionally an architect acts as the construction manager on projects, most often small-scale projects, such as house additions and renovations. Construction management is not a licensed activity in most provinces.

Construction managers can serve in different capacities with varying degrees of authority and responsibility (advisor, agent or constructor). Depending upon how the project is organized, a construction manager can:

- act as an advisor during a particular phase of the design, documentation or construction process;

- manage the construction of the project, with the owner contracting directly with each trade contractor. The construction manager may or may not assume responsibility for construction activities typically outlined in the general conditions of the specifications (for example, temporary facilities, site layout, clean-up). The fee paid to the construction manager is relative to the services to be performed.

Construction Management Contract for Services (CCDC 5A) vs. Construction Management Contract for Services and Construction (CCDC 5B)

At the beginning of a project, the construction manager will develop a construction budget. Construction will commence based on the budget, and as each tender package is released and subtrade contracts awarded, the budgeted construction cost becomes closer to an actual cost. In a CCDC 5A contract, the construction manager is paid for the services delivered based on either a fixed fee, a percentage of construction cost, or an hourly rate. The construction manager is not at risk should the actual cost of construction exceed the budget. Construction management uses an “open book” accounting system where the bids received from subtrades are known by both the owner and construction manager.

CCDC 5B is a hybrid that combines elements of CCDC 5A, fee for construction management services, with CCDC 2, a guaranteed price for construction work. A construction manager for services and construction (also known inaccurately as “at risk”) provides the owner with a construction budget and a guaranteed maximum price (GMP). It is common for a construction manager to assume financial liability for the project and become “at risk” once sufficient bid packages have been received from subtrades and the actual cost of construction can be assured. Architects and engineers who provide construction management services may decline to provide those services for construction as well, largely based upon a combination of lack of expertise and lack of appropriate insurance.

Refer to Canadian Construction Association’s A Guide to Construction Management Contracts.

Refer to CCDC 5A – Construction Management Contract for Services and CCDC 5B – Construction Management Contract for Services and Work and their guides.

Typical responsibilities of a construction manager include:

- assisting in preliminary planning relative to the design requirements for the project;

- advising on schedules, budgets and costs of various alternative methods, on material selection and availability, and on detailing during the design phase;

- advising on and arranging for services and trade contractors and suppliers to carry out the various phases of the work;

- planning, scheduling, coordinating and supervising the activities of trade contractors;

- providing technical and clerical services in the administration of the project.

Advantages:

- the construction manager has a direct contractual relationship with the owner;

- advice on constructability and cost is available to the design team during the design process;

- the opportunity exists to call bids sequentially, thus accelerating the project schedule by permitting a start on construction before all documentation has been completed (“fast track”);

- careful monitoring of costs and schedule can occur (different checks and balances apply during design and construction because the architect, trade contractors, and construction manager are independent entities).

Disadvantages:

- construction usually commences before the total costs are known, thereby introducing risk inherent in fast-tracking project work;

- added costs and time in the selection of an additional consultant;

- more complex relationships leading to the need for additional communications to clarify roles and responsibilities;

- the professional relationship between architect and owner, and architect and contractor, now includes a third party, sometimes complicating direct communication;

- less control over the final cost in an unstable construction market;

- as with some other forms of project delivery, change orders and delay claims are possible from prime or trade contractors who bid too low;

- there may be conflicts of interest if there is no independent cost consultant and the construction manager will be undertaking some of the construction work;

- the owner, as the “constructor,” is required to accept the responsibility for construction safety, unless transferred to the construction manager for services and work;

- multiple construction contracts increase administrative costs for the owner and the potential for coordination problems.

Design-Build

In design-build, the owner contracts with a single entity to provide both design and construction. The design team is retained by the design-builder rather than the owner.

The point in the program’s life cycle at which the owner hires the design-builder may vary, depending on the complexity of the project and the owner’s need to develop detailed requirements. Broadly speaking, there are two variations on design-build.

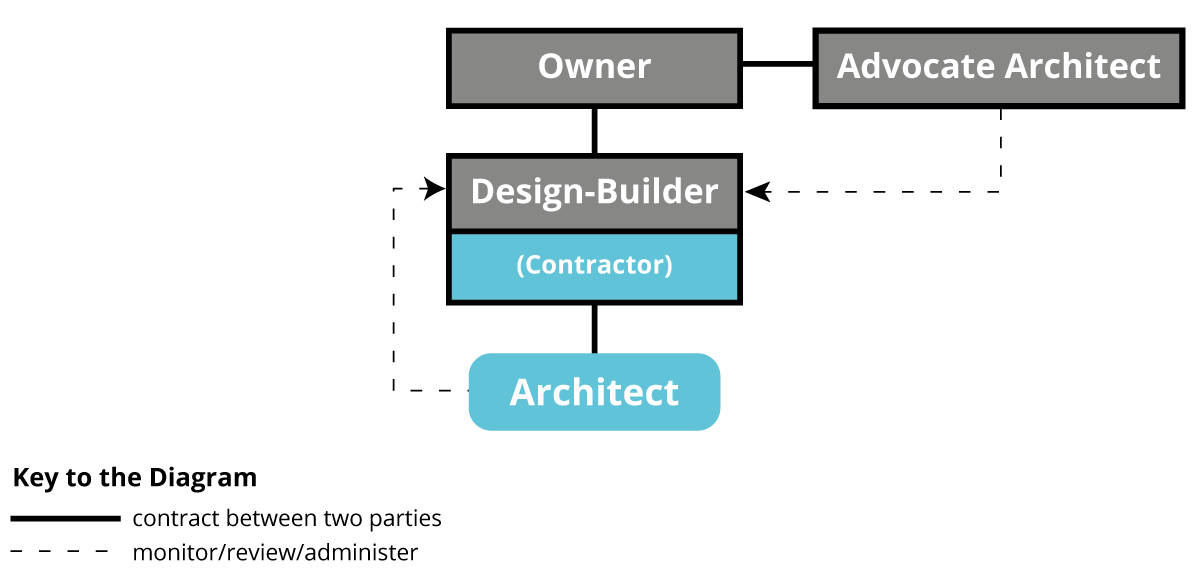

Owner, Advocate Architect and Design/Builder

The owner will engage an “advocate” architect (sometimes called a “bridging” consultant or owner’s advisor) to prepare the owner’s statement of requirements. The advocate architect may also prepare one or more conceptual design solutions as a means of testing the statement of requirements. The advocate architect provides advice to the owner in the hiring of the design-builder and throughout construction. The advocate architect acts in the interests of the owner.

The advocate architect role also frequently occurs in public-private partnerships (P3).

See Chapter 3.10 Appendix D – The Architect as Advocate Architect/Compliance Architect/Design Manager/Researcher for additional discussion.

Figure 2 Bridging

Advantages:

- the project’s statement of requirements is developed with a focus on the owner’s interests, independent of the interest of other parties;

- the owner benefits from the support of a knowledgeable and independent professional advising them in project decision-making, from design through to take-over.

Disadvantages:

- the fee for the advocate architect is in addition to that for the design-builder;

- the duration of the total project may be extended, as additional time may be required for the independent statement of requirements to be developed;

- communications between designers and the client may be restricted by the design-builder relationship;

- the architect’s requirement to act in the public interest may be more difficult to manage.

Owner and Design-Builder

The owner retains a design-builder. A separate design team working for the design-builder prepares design documentation and provides general review during the construction. The design-builder may support the owner in the development of the owner’s statement of requirements. There is a single design team working for the design-builder. Design-build projects usually have two phases:

- Phase 1: The design-builder, possibly in competition with other design-builders, provides the owner with a building design and related cost information and, throughout the design process, monitors costs to ensure the building remains within the owner’s budget. Based on the design developed, the design-builder usually proposes a stipulated maximum price, which includes a fee for managing the construction.

- Phase 2: The parties enter into a stipulated price contract for the completion of the building. It is also possible to have a cost-plus fee agreement in the design-build method of project delivery. The builder works to save costs during construction. Any savings accrue to the owner, who pays only the actual cost of construction, plus the design-builder’s fee.

Refer to CCDC 14 – Design-Build Stipulated Price Contract and to CCDC 15 – Design Services Contract Between Design-Builder and Consultant.

Advantages:

- functional program (statement of owner’s requirements) and owner’s decisions are committed early;

- cost-benefit analysis is addressed early in the design process;

- more immediate feedback is received from the contractor on design options;

- streamlined processes may increase efficiency of design production and construction;

- the team approach is reinforced.

Disadvantages:

- the responsibility for design approvals shifts from the owner to the design-builder;

- decisions by the design-builder may be based more on initial cost rather than on design or long-term value;

- the construction budget is determined before the design is complete;

- the architect’s role as leader of the design team may be reduced;

- there is a higher cost risk to the architect for preparing the proposal, which may or may not be successful;

- there is greater potential for tension between the “regulated” professional (architect) and the “unregulated” building contractor;

- there is greater potential for a lack of communication between the architect and the owner or building users;

- without an advocate architect, the owner loses the benefit of independent advice in reviewing construction costs and design options as well as independent payment certification.

Refer also to the Design-Build Practice Manual published by the Canadian Design-Build Institute.

It is not uncommon for a design-builder to expect the architect to absorb some or all pursuit design costs associated with preparing preliminary designs in competing for a project. The competition to obtain the project’s commission often involves much more work on the part of the architect than any other member of the team. As a result, the architect has more at risk than other members of the design team. When architects are engaged by a design-builder to become part of a design-construction team in competition for a project, architects should insist on being compensated for their professional services. In some jurisdictions, it may be against regulations for an architect to provide services without compensation.

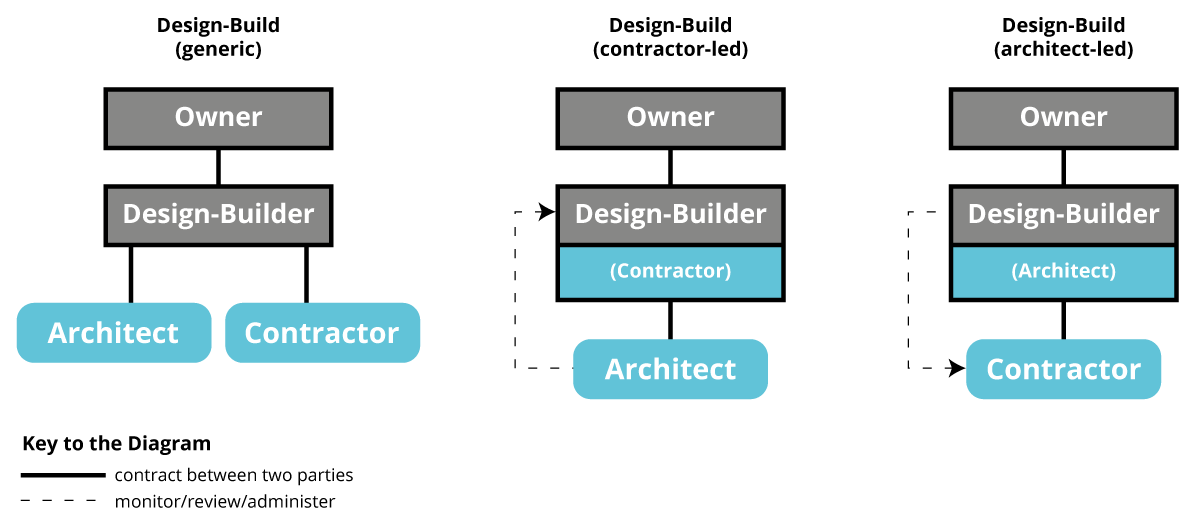

The following figure presents the contractual relationships between the owner, architect and design-builder in three different contractual scenarios.

Figure 3 Design-Build Contractual Relationships

Design-Bid-Build, Construction Management and Design-Build Compared

The three common project delivery methods place the architect in different positions in the design-construction supply chain, and therefore in different places from which to influence the primary project decision-maker, the owner.

In working with owners, design-builders or construction managers, the architect must develop strategic approaches to address the needs of the project and the key project decision-makers. For example, the design-build project delivery method changes the architect’s traditional position in the design-construction supply chain. Where the architect traditionally has a direct relationship with the owner, in the design-build delivery method the builder mediates in the owner-architect relationship. The architect must address the needs of the design-builder for speed of production and cost efficiency as well as the owner’s statement of requirements. This risk may be mitigated in architect-led design-build teams.

(Descriptive and risk comparison text and tables are excerpts from the RAIC’s A Guide to Determining the Appropriate Fees for the Services of an Architect.)

Managing Project Risk and the Project Delivery Method

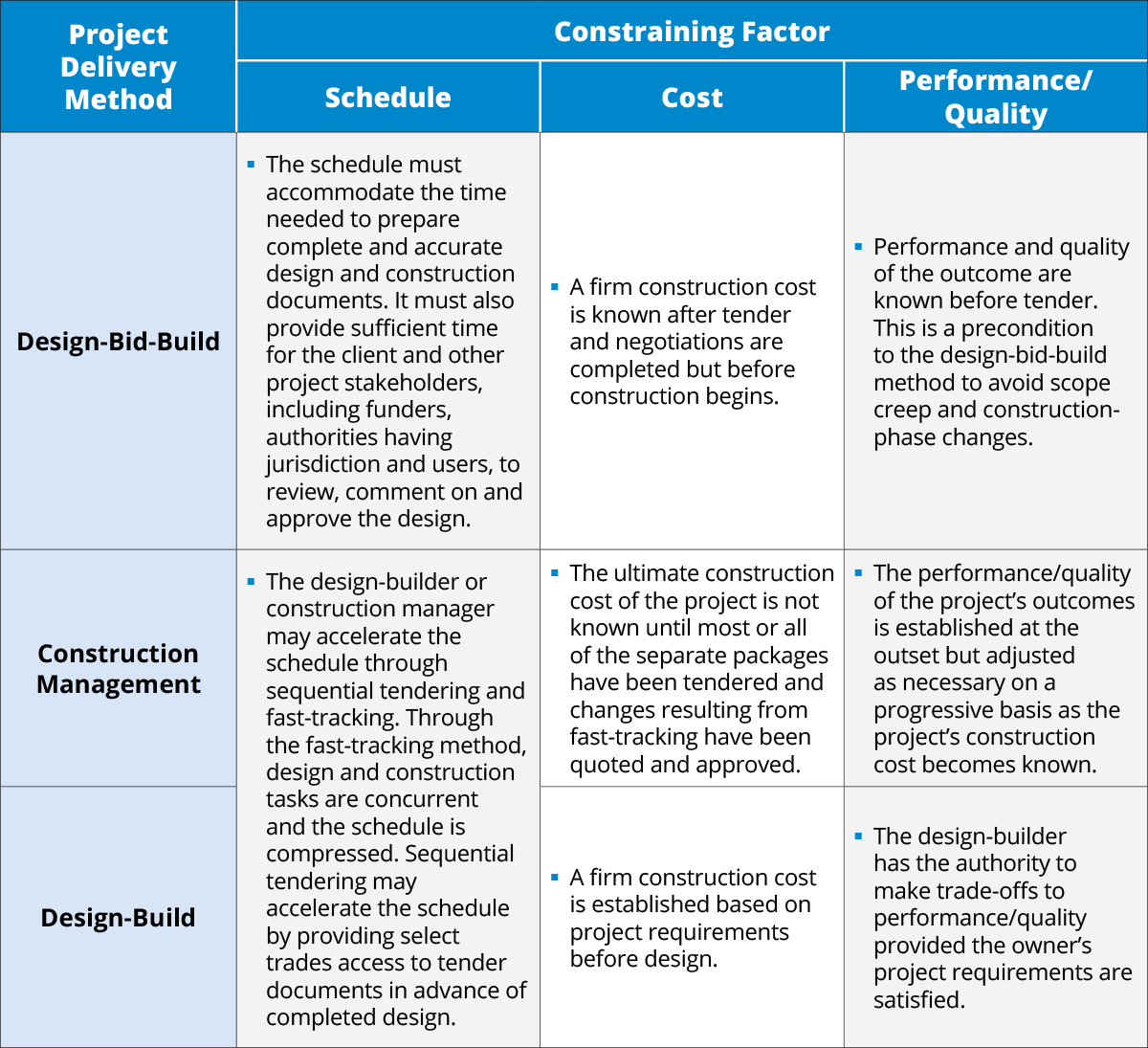

Each form of project delivery has its own benefits and drawbacks. At the risk of over-simplification, these benefits and drawbacks are compared using a traditional project triple-constraint model where the scope of the project is assumed to be fixed. The constraints are time (schedule), cost, and performance/quality.

TABLE 2 Constraining Factors in Project Delivery Methods

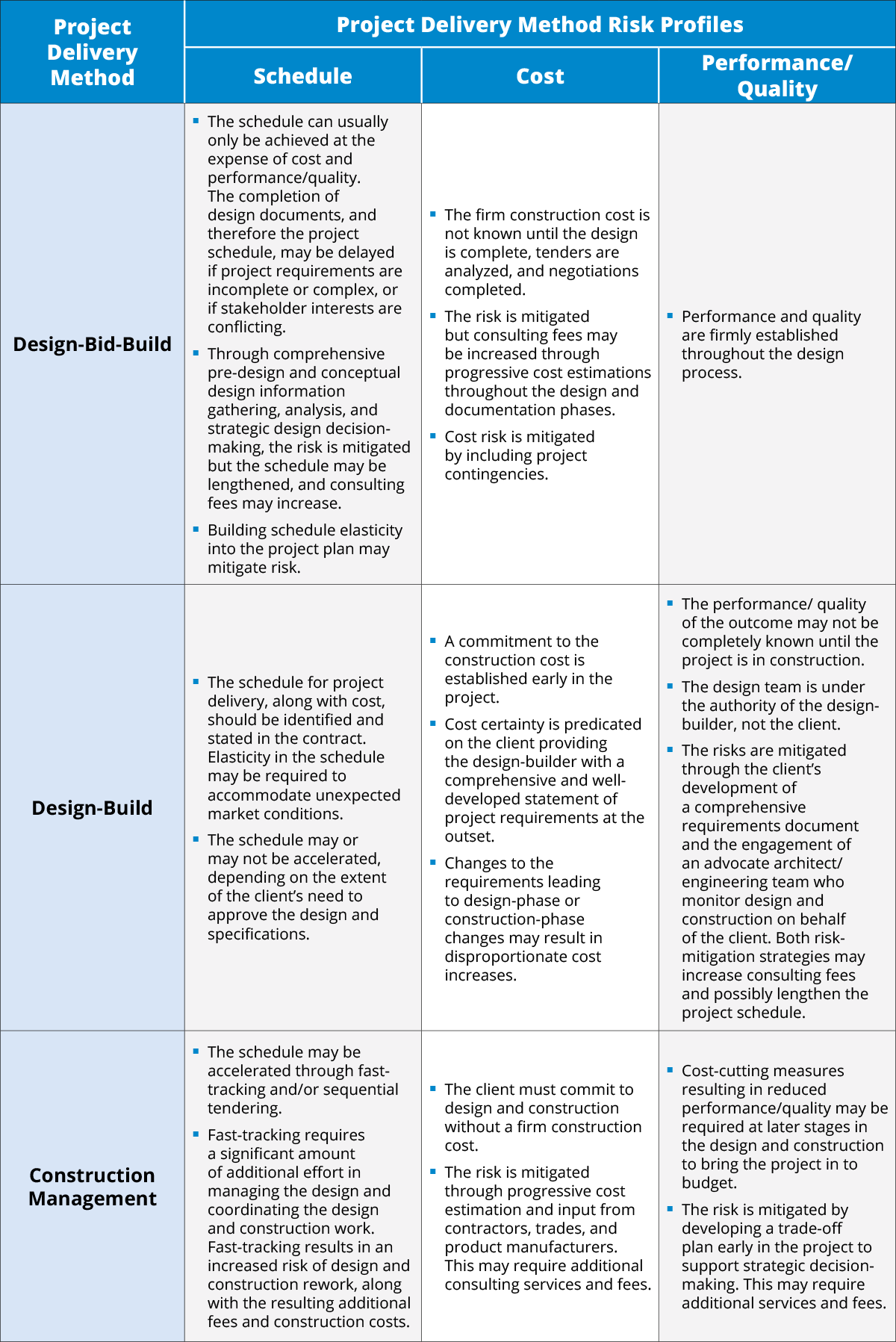

Change and uncertainty are inherent in undertaking projects. Project endeavours and risk are inseparable, and no amount of planning can remove all project risks. Again, at the possibility of over-simplification, each design/construction project delivery method has a general risk profile. To establish a fair exchange of value, the client and architect must recognize alignment of the project delivery risk profile with their respective risk sensitivities.

TABLE 3 Project Delivery Methods and Risk Profiles

Public-Private Partnership

Public-private partnerships or P3s (called “alternate financing and procurement” or AFP in Ontario) are generally used for infrastructure (civil engineering works) and larger scale public buildings; however, some governments “bundle” several small buildings of the same type into one P3 contract.

P3s occur when a private sector consortium is engaged by a government or other public agency to deliver a complete capital program. The scale of a P3 project usually is significant and may include financing, design, construction, and very often facilities management and operations.

The P3 approach is controversial as it fundamentally alters the supply chain relationships in the design-construction sector. Critics of the process argue that the cost of P3 projects exceeds the cost of the same projects delivered under more traditional forms of project delivery because of the costs for financing and the hidden costs of “risk transfer” to the private sector. Instead of lump sum impacts on government budgets, P3s often divide the total cost impact over the project’s operating life, resulting in an apparently smaller annual cost. Governments and public agencies argue that these projects would not have been possible under traditional government processes using public funds. Furthermore, they argue that these projects can be delivered more quickly through P3s in response to the growing “infrastructure deficit.”

Advantages:

- uses the efficiencies and expertise of the private sector for public sector projects;

- allows projects to be financed in ways which may not be possible through public methods (such as debentures, taxation, etc.) and may not be accounted for as a capital expenditure;

- with private sectors operating the facility, life cycle costs may be reduced;

- single point responsibility;

- architects may develop long-term relationships with ongoing consortia (project entities);

- reduced time and construction schedule to deliver projects, compared with traditional public sector methods;

- design often becomes the “differentiating” quality in a proposal.

Disadvantages:

- transfers or allocates certain financial risks to the private sector;

- inappropriate transfer of business or non-insurable risk from the government to the proponent, then to the architect;

- “best value” is not always achieved, as initial capital costs sometimes become overly important;

- costly for architects and consultants to participate in pursuits, as pursuit fees may not cover costs;

- obstructions in the communication channels between the architect and the owner or building users as procurement concerns overshadow long-term building use and operation;

- building users have less control over the process and its outcomes;

- building owners have less control over the quality of the project and facility operations;

- professional liability insurers may place restrictions on coverage;

- difficult for small architectural practices to compete in this market.

Integrated Project Delivery (IPD)

The integrated project delivery (IPD) method builds on the concept that when all players in the design-construction endeavour share the same method of reward, collaboration towards higher building performance, increased value, and cost savings can be achieved. The IPD approach combines elements of other project methods but also represents innovation in the design-construction process. Rather than the adversarial approach that is created in traditional contractual relationships, the IPD involves a multi-party contract in which the owner, architect, engineers, constructor and major trades share in the rewards of the successful project.

In terms of the design-construction program described above, the integrated project delivery (IPD) method is designed to break down the envelope between the design project and the construction project. The IPD contract is a restructuring of the traditional multi-project approach to form a single project with a single project team. Its aim is to create a more harmonious and collaborative working environment that will result in buildings meeting much higher performance standards and significantly increasing value for the owner. Collaboration is promoted through executive, planning and implementation teams, each with representatives of all of the major parties. Constructive collaboration is the cornerstone to this approach.

The four major phases of the integrated project delivery approach are validation, design, implementation, and warrantee.

During the validation phase, the project management team (PMT) validates the project’s objectives, including requirements, scope, quality, cost and schedule, and a determination of the project’s feasibility is made. If the project appears unfeasible at this point, the owner may decide to abandon the project. The parties to the agreement would be compensated with costs but no profit.

The project management team coordinates the design activities and prepares for implementation of the design during the design/procurement phase. The project implementation team (PIT) is established to support the PMT. The project’s final target cost is determined, as well as the amount of the “risk pool.”

The PMT oversees construction during the construction phase. Lean construction methods are promoted in order to increase value to the owner and the team.

The warrantee phase sees the resolution of deficiencies and the final distribution of the risk pool.

Advantages:

- inefficiencies of the traditional construction methods are reduced;

- both efficiency and effectiveness of the design in terms of constructability are enhanced;

- transparency of communications between parties of the same contract;

- constructability is improved and rework for both design and construction is reduced;

- incentive for all project parties to enhance performance to maintain the schedule.

Disadvantages:

- project management and collaborative activities (meetings) require greater commitments of time and effort than traditional project delivery methods;

- the owner must be fully engaged in the project;

- negotiation and balancing of interests become important to success (check the ego at the door);

- non-collaborative and win-lose attitudes may result in additional project work and possible reduction of the amount of the risk pool remaining at project completion.

For a detailed discussion of the legal and contractual aspects of the integrated project delivery method, refer to Howard W. Ashcraft’s article in CCCL Journal 2014, Integrated Project Delivery Agreement – A Lawyer’s Perspective.

For the Canadian standard form of agreement for integrated project delivery, refer to CCDC Document 30 – Integrated Project Delivery Contract.

Collaborative Culture

“Culture … refers to a commonly shared set of values, beliefs, attitudes and knowledge. Culture can be created by both people and environment and can be transmitted from one generation to the next through family, school, social environment and other agencies.”

Verma, p. 89

The competitive and cost-obsessed culture of the design-construction industry does not easily lend itself to undertakings that require collaborative participation to succeed. Transforming a culture of competition to one of collaboration does not happen by accident or without effort and resources. The Canadian Practice Manual for BIM (CPMB) outlines a planned process for creating the type of collaborative culture needed to implement both BIM and IPD. Key elements of the planned approach are:

- making a decision to commit to the collaborative process;

- establishing and communicating the value that a collaborative has in contributing to project success;

- leading by establishing the vision and resources;

- viewing the resources applied to BIM (and collaboration) as an investment;

- developing an implementation strategy, including training;

- supporting cultural transformation with buy-in at all levels of the project organization and among all project stakeholders.

Refer to The Canadian Practice Manual for BIM, Volume 2 – Company Context, Chapter 2 – Creating Culture, Commitment and Support for additional discussion of creating cultural transformation towards collaboration.

Other Forms of Project Delivery

Other management and project delivery methods include:

- project management;

- just-in-time;

- turnkey development;

- unit rates;

- lease-back;

- cost-plus.

Project Management

Project management, when defined as a project delivery method, is an adjustment to the design-construction supply chain. In this method, an owner retains the services of a project management firm to oversee the program of planning, design and construction projects. Put simply, it is the replacement of the owner’s representative with an out-sourced firm. The project manager may work either as a consultant, advising the owner and reporting project progress, or on behalf of the owner, retaining the services of the consulting design professionals and constructor. In the former instance the project management firm is referred to as the “agent,” and in the latter as the “primary.”

The main difference between “project management” and “construction management” is that under project management the project manager acting as the primary has a contract with a client and in turn employs the architectural and engineering consultants, whereas under construction management the owner engages the architectural and engineering consultants, and at the same time or shortly afterwards engages the services of a construction manager.

The project manager (PM) is usually hired by an owner during the pre-design phase to manage the entire project and engage all the disciplines required, including the architect and the consulting engineers. The typical project management project may have the same three phases (design-bid-build) as traditional project delivery, or it may use sequential tendering to achieve earlier completion.

Advantages:

- transfer of project management risks from the owner to the project management firm;

- as in construction management, the design team may receive constructability and construction cost information during design.

Disadvantages:

- this arrangement is NOT permitted by provincial regulation in several jurisdictions where the architect must be engaged directly by the owner;

- unless the architect can maintain a direct link with the owner, the owner’s ability to control construction quality is reduced because efficiencies or cost reductions implemented by the PM that affect quality may not be discussed directly with the owner.

Just-in-Time

This approach combines aspects of fast-tracking, partnering, systems architecture and strong incentives for repeat work. Large projects are broken into small work packages. Small teams of architects and contractors program, plan, demolish and construct these areas on an hourly basis driven primarily by schedule, where time is the most critical factor.

Turnkey Development

Turnkey is generally described as a project delivery method that includes various real estate functions as well as design and construction.

These functions may include site acquisition, entitlements, construction and/or long-term financing or other functions. This method may be carried out under design-build or developer proposal methods.

Unit Rates

Use of this method is limited primarily to heavy civil engineering work – such as roads and site preparation – where the contractor is paid for measured quantities at quoted unit rates. The method could be appropriate for the cost of repetitive units or identical buildings. The architect should ensure that unit rates are applied only to the design and documentation phases. The bidding and contract negotiations phase, as well as the contract administration phase, require full services.

Lease-back

Under this method, the project is financed, constructed and owned by the builder, and the building is “leased back” to the owner.

Cost-plus

In the cost-plus method, the contractor is compensated for the actual costs of the work, plus a fee. The fee is based on:

- an agreed-upon fixed sum; or

- a percentage of the cost of the work.

Often called “time and materials,” this method is appropriate for small, complicated projects in which time is a factor or total costs are initially difficult to determine. A variation of cost-plus is “cost plus to a maximum upset price” or guaranteed upset price. The cost-plus method normally uses the CCDC 3 – Cost Plus Contract. It is now frequently replaced by the construction management delivery method, which includes many of the advantages and few of the disadvantages.

Advantages:

- costs are based on actual quantities and mark-ups with no “unknown factor”;

- suitable when time frame is more important than construction costs (saves time because a formal tender call is not required);

- flexible in response to unknowns at the start of construction;

- suitable where extraordinary quality is required;

- construction may begin before the design is complete.

Disadvantages:

- no incentive to avoid cost overruns;

- often not permitted on publicly funded projects;

- total cost is unknown until project completion.

Contractors

Each type of project delivery has variations which can be organized to suit the requirements of the project and the involvement of the contractor. Selecting the contractor best suited to the project delivery is an important decision.

Pre-qualification of Contractors

The purpose of pre-qualification is to ensure that the selected contractor is capable of delivering the quality and value specific to the project requirements. The client, through pre-determined criteria, eliminates candidates who cannot demonstrate that they have the necessary financial capacity, technical expertise, managerial ability and relevant experience for the project at hand. Pre-qualification is rarely used for public projects, where the opportunity to be considered the contractor must be open to all. See also Chapter 6.5 – Construction Procurement.

CCDC 11 – Contractor’s Qualification Statement is the standard document used for pre-qualification.

Multiple Contracts

There may be a variety of reasons to have multiple contracts for one project, such as:

- two or more general contractors are working on the same site;

- there is a need for sequential tendering for different parts of the project;

- the owner may be undertaking some of the work with their own forces, concurrent with a general contractor.

Some provinces have legislation which defines the owner as the “constructor” when there are multiple contracts. This has the effect of making the owner responsible for safety at the construction site. The owner may engage one of several contractors to be the prime contractor. The prime contractor is then responsible for construction site safety. The other contractors and subtrades on the site are required to take direction and follow the instructions of the prime contractor.

Sequential tendering is sometimes required for different parts or phases of a project; in this instance, separate bid packages are issued for these parts, usually in the same sequence as required for construction (such as site work, foundations, structural shell, etc.). Sequential tendering requires additional administrative work on the part of the architect to conduct multiple tenders and administer multiple contracts.

Types of Construction Contracts

Standard Forms of Contract

The construction industry has recognized the advantages of jointly preparing standard forms of contract. Many of the documents are developed and endorsed by the Canadian Construction Documents Committee (CCDC).

See Chapter 2.1 – The Construction Industry for the composition and role of this committee.

The Canadian Construction Documents Committee (CCDC) publishes standard contract forms, including:

- CCDC 2 – Stipulated Price Contract;

- CCDC 3 – Cost Plus Contract;

- CCDC 4 – Unit Price Contract;

- CCDC 5A – Construction Management Contract for Services;

- CCDC 5B – Construction Management Contract for Services and Construction;

- CCDC 14 – Design-Build Stipulated Price Contract.

The forms, which are available in both English and French, are subdivided into three parts:

- agreement between owner and contractor;

- definitions;

- general conditions.

The use of CCDC standard contract forms is recommended. Because each document is reviewed periodically by the CCDC and revised as required, the architect should obtain and complete the latest edition when preparing construction contracts for the client’s use and execution.

See “Appendix A – List: Canadian Construction Documents Committee Contract Agreement Forms and Guides” and “Appendix B – List: Canadian Construction Association Contract Form and Guides” at the end of Chapter 2.1 – The Construction Industry.

Stipulated Price Contract:

CCDC 2 – Stipulated Price Contract and CCDC 20 – A Guide to the Use of CCDC 2

This is the most common type of fixed-price contract. The stipulated price is established through bidding – either open bidding or an invitation for bids from pre-qualified bidders. The successful contractor is paid a fixed price for the completed construction. The fixed price or time for construction can only be adjusted by change orders.

The contractor is required to perform work called for in the contract, regardless of what it actually costs. Thus, the contractor must take great care when pricing such work, taking into account potential cost increases caused by inflation, material shortages, or difficulties in meeting performance requirements.

A stipulated price contract can produce maximum profit for the contractor, who also assumes maximum risk, including the risk of unexpected additional costs such as those that might result from inflation or material shortages. This type of contract should be used when the construction costs are reasonably predictable and when full documentation is available.

Design-Build Stipulated Price Contract:

CCDC 14 – Design-Build Stipulated Price Contract

In the design-build stipulated price contract, the owner deals with one single business entity, which arranges to provide both design services and construction of the project under one contract package. Prices established before the design is completed may cause disagreement over the scope of the work or the details of construction intended for inclusion in the stipulated price.

The prime contract is between the owner and the design-builder, where the design-builder could be a contractor, an architect, a broker, or a joint venture between a contractor and an architect.

The architect should contact the respective provincial or territorial association to verify regulations concerning the architect’s role as a design-builder, and for joint venture restrictions. The design-builder’s consultants are the only consultants recognized in the contract, although the owner may also appoint an advocate architect or other consultants to represent the owner’s interests.

A second contract (CCDC 15 – Design-Builder/Consultant Contract) is between the project’s design-builder and the architect.

Cost Plus Contract (percentage or fixed fee):

CCDC 3 – Cost Plus Contract and CCDC 43 – A Guide to the Use of CCDC 3

In a cost-plus contract, the contractor is compensated for the actual costs of the work, plus a fee based upon either an agreed-upon fixed sum or a percentage of the costs. Often called time and materials, this method is appropriate for small, complex projects in which total costs are initially difficult to determine.

A cost-plus contract is one of the simplest types of cost-reimbursement contracts. It has the following features:

- the owner reimburses the contractor for the allowable costs incurred in the course of construction;

- costs are paid regardless of the progress of the work and no matter how far the task is from completion;

- work may cease when the construction costs equal the funds provided for under the contract.

Guaranteed Maximum Price Contract:

CCDC 3 – Cost Plus Contract with Guaranteed Maximum Price Option

In this type of contract, the contractor is compensated for the actual costs, plus a fee with an agreed-upon maximum price. This is sometimes called an upset price contract. The contractor bears all costs beyond the pre-determined maximum. If the actual costs are below the maximum, the contractor may share the savings with the owner, depending on the terms of the contract. The guaranteed maximum price can be adjusted only by a change order.

Unit Price Contract: CCDC 4 – Unit Price Contract

In a unit price contract, the contractor is paid a pre-determined price for each unit or quantity of work or material used in the project’s construction. The unit price can be derived through bidding or negotiation. The actual quantities involved are generally verified by independent inspection; for example, by a clerk of the works or a quantity surveyor.

Unit prices form the basis for payment of the contract price. Quantities in the schedule of prices are estimated. The contract price is:

- the final sum of the product of each unit price stated in the schedule of prices, multiplied by:

- the actual quantity of each item that is incorporated in or made necessary by the work; plus

- lump sums and allowances, if any, stated in the schedule of prices.

Currently, CCDC 4 – Unit Price Contract has limited use in Canada for building construction. It is used primarily for civil engineering work.

Other Types of Contracts

Other types of construction contracts include:

- government or “in-house” contracts;

- contracts with economic price adjustment;

- incentive-based contracts;

- standing offer contracts;

- purchase order contracts;

- oral contracts.

Government or “In-house” Contracts

Various federal, provincial and municipal governments have their own forms of contract which include different general conditions. These documents are printed forms, and normally are not amended.

In some instances, a public body or large corporation will choose to prepare its own forms of contract for construction. The architect required to administer these documents should review these contracts prior to providing a proposal for contract administration services.

See Chapter 3.8 – Risk Management and Professional Liability for the pitfalls in the use of non-standard contracts.

Contracts with Economic Price Adjustment

Some fixed-price contracts contain economic price adjustment clauses that protect the contractor and the client against wide fluctuations in labour or material costs when market conditions are unstable. These clauses may provide for adjustment of the contract price for increases or decreases from an agreed-upon level measured against the following:

- published or established prices of specific items;

- specified costs of labour and material actually experienced during performance;

- specified labour or material cost standards or indices, such as the consumer price index.

Incentive-based Contracts

Incentive-based contracts are also known as incentive contracts, cost-plus-incentive-fee contracts, and cost-plus-award-fee contracts.

The contractor and the owner’s contracting officer agree on:

- target cost;

- target profit;

- target fee;

- incentive formula for determining the final fee.

The formula provides for an adjustment in the fee, based on any difference between the target cost and the total allowable cost of performing the contract. The award amount paid varies according to the client’s evaluation of the contractor’s performance in such areas as:

- quality;

- completion time;

- ingenuity;

- cost-effective management.

Standing Offer Contracts

Government or institutional clients may retain one or more consulting firms, or construction companies pre-qualified by proposal call, to provide professional or construction services on an as and when requested basis (sometimes referred to as being “on retainer” or “on call”). Occasions arise when consulting or construction services are required to augment existing resources within a professional and technical services branch of government. Such a situation can encompass:

- peak workload relief;

- project review to ensure a higher degree of performance;

- situations where in-house expertise is not available.

Purchase Order Contracts

Authorized officials (public or private) may purchase design and construction services not exceeding a stated amount using purchase orders. The use of purchase orders is usually restricted to:

- small transactions;

- one delivery and one payment;

- off-the-shelf items;

- small repairs.

A purchase order may refer back to the conditions of a standard form of agreement such as RAIC Document Six.

Oral Contracts

“A verbal contract isn’t worth the paper it’s written on.”

Samuel Goldwyn, movie producer

Oral contracts should never be used. All agreements should be in writing and may be required in some jurisdictions. Written client-architect agreements are a regulatory requirement in several jurisdictions in Canada.

References

Allison, Markku, et al. Integrated Project Delivery: An Action Guide for Leaders. Integrated Project Delivery Alliance, 2019.

American Institute of Architects (AIA). Handbook on Project Delivery. The AIA California Council, 1996.

Ashcraft, Howard W., Jr. “Integrated Project Delivery Agreement—A Lawyer’s Perspective.” Journal of the Canadian College of Construction Lawyers, 2014, pp. 105-156.

Dickinson, John K., and Paul Woodard, eds. Canadian Practice Manual for BIM. buildingSMART Canada, 2016.

Dorsey, Robert W. Project Delivery Systems for Building Construction. Associated General Contractors (AGC) of America, 1997.

Fisk, Edward R., and Wayne D. Reynolds. Construction Project Administration, 10th Edition. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2014.

Gould, Frederick E. Managing the Construction Process: Estimating, Scheduling, and Project

Control, 4th Edition. Boston, MA: Prentice Hall, 2012.

Kerzner, Harold. Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling, and

Controlling, 12th Edition. John Wiley and Sons, 2017.

Lewis, James P. The Project Manager’s Desk Reference: A Comprehensive Guide to Project Planning, Scheduling, Evaluation, Control Systems, 3rd Edition. McGraw Hill, 2007.

Moore, Dale. “Selecting the Best Project Delivery System.” Project Management Institute. September 7, 2000. https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/selecting-best-project-delivery-system-8910, accessed March 30, 2020.

Pierce, David R., Jr. Project Scheduling and Management for Construction, Second Edition.

R.S. Means, 1998.

Verma, Vijay K. “Managing the Project Team.” The Human Aspects of Project Management, Volume Three. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute 1997.

Weaver, Patrick. “Understanding programs and projects—oh, there’s a difference!” Project Management Institute, February 24, 2010. https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/understanding-difference-programs-versus-projects-6896, accessed March 30, 2020.