Introduction

A relevant architectural profession and a sustainable and flourishing practice allow practitioners to travel a pathway that, though it may be different for each individual, accommodates transition throughout their professional lives. This chapter discusses the growth and changing roles of the professional as they move through the different phases of their architectural career, and the role that a mentoring relationship has in supporting those transitions. Architects have a professional and ethical responsibility to pass along their body of knowledge to the next generation. By mentoring, architects can support those entering the profession. As architects become capable practitioners, they grow into the role of proprietors, or retire from practice.

Career Transitions Within the Practice of Architecture

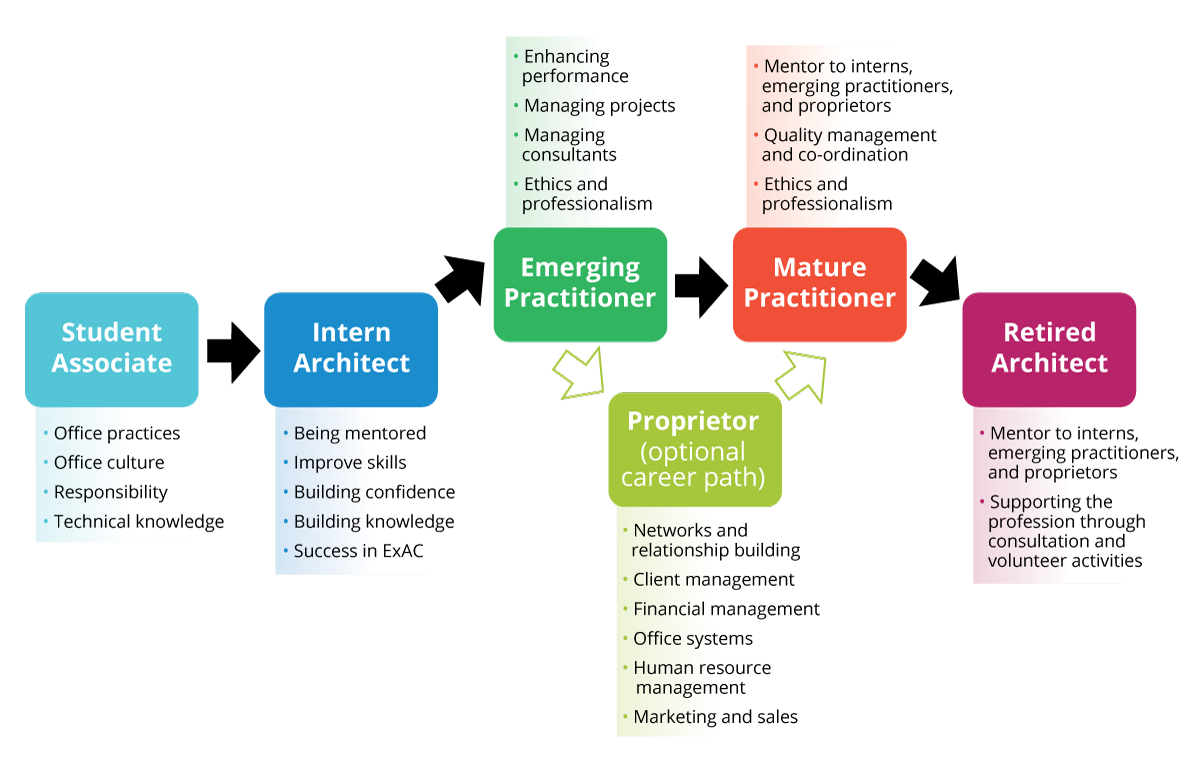

Career transitions refers to the milestones typical of an architect’s career in practice. The common transitions are student to intern, through to the emerging and then mature practitioner. Some architects may become a proprietor with firm ownership responsibilities. Ultimately an architect will transition to retirement and the

role of non-practising architect. Not all possible pathways can be explored in this chapter. Architects may transition from the role of private-sector practising architect to public-sector project manager or other variation in a career pathway.

As architecture is a lifelong commitment and the architect is always learning, evolving and improving their skills, these categories are not always linear and cannot capture all the nuances and overlap of an individual’s career. For example, a student will not always be young, and some hit their stride as mature practitioners at a very young age. Alternatively, some mature practitioners do not take up the mantle of ownership or do so quite late in their careers.

It is also important to appreciate that there is no one correct course to or through the pathway of a life in architectural practice. Each individual has a different and personal definition of success. The correct career path is the one that leads them to that vision.

FIGURE 1 Traditional pathway through architectural practice

Student Associate

“The mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be ignited.”

Plutarch

In many jurisdictions, a student may be recognized by their provincial or territorial association of architects as an affiliate, associate or student member. The student must either be studying architecture at a Canadian school of architecture accredited by the Canadian Architectural Certification Board (CACB) or an American school of architecture accredited by the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB), or be enrolled in the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada’s (RAIC) Syllabus Program.

Students enjoy the benefits of becoming engaged in the profession, with opportunities to volunteer in their architectural association’s programs and build strong professional networks, and often enjoy reduced rates to conferences and events sponsored by the association. Students and RAIC Syllabus students may also able to log experience towards their internship experience requirements. Please refer to local licensing authorities for specific conditions and further information.

Internship

“The internship is a chance to develop the relationship between theory and practice, for each should inform the other.”

Sgroi & Ryniker, 2002

Note: The term “intern architect” is not universally recognized as an official designation in the acts regulating architectural practice across Canada nor permitted in some jurisdictions. Individuals must refer to the regulation in their jurisdiction for the proper term. In the Canadian Handbook of Practice for Architects, the term “intern” is used to denote an individual at the beginning of their pathway toward professional licensure.

An intern is an individual who has graduated with a professional degree or professional diploma in architecture, is an intern member of their provincial or territorial association, and is gathering practice experience under the supervision of an architect licensed to practice in Canada. Internship is a very important stage in one’s career. It exposes the person to the rigours and demands of the profession. It is a time when knowledge about the practice of architecture is transferred and also a time for assessing whether they want to pursue a career in architectural practice.

An intern acquiring practice experience will qualify to undertake the Examination for Architects in Canada (ExAC) after the required number of hours have been reviewed and approved. As a part of the three E process to achieve architectural licensure (education, experience, and examination), this examination tests whether the intern has attained the minimum standards of competency required to practise architecture. Passing the examination demonstrates that the intern understands their responsibility towards protecting the interests of the public and supporting the profession and has the capability to deliver architectural services with the standard of care expected of a professional architect.

Depending on the jurisdiction, a pre-licensure admissions course and/or interview before a panel of architects may also be mandatory to become a registered architect on the path to architectural licensure.

To be eligible to register for the Internship in Architecture Program (IAP) an individual must have graduated with a professional architectural degree or professional diploma from a CACB or NAAB accredited post-secondary institution or have completed the RAIC Syllabus Program. International graduates must demonstrate compliance of their education credentials through the CACB certification process, and those who graduated from an approved Canberra Accord signatory country may receive substantial equivalency status. At the internship stage, it may be required that the intern recruit a mentor to advise, support skills development, offer counselling in leadership, and help build confidence.

For the intern, a professional relationship with a supervising architect becomes an important element to their journey for licensing.

“The supervising architect is the Architect within the architectural practice or place of employment who personally supervises and directs the Intern on a daily basis … to assess the quality of work performed and regularly certify the Intern’s documented architectural experience prior to submission of each section of the CERB”.

Internship in Architecture Program, p. 7

For further information, please refer to the Internship in Architecture Program guidelines published by the Canadian Architectural Licensing Authorities or your local jurisdiction.

Emerging Practitioner

An emerging practitioner can be defined as one that is newly licensed or to whom registration has recently been issued by a licensing authority.

When starting on a career path, it is important for a newly licensed architect to consider their long-term career goals, specialization in project types or practice focus, and the type of work environment ideally suited to the architect’s capabilities, work habits and temperament. Early projects in one’s career may become an individual’s specialty later as their experience and reputation grow. The choice of whether to specialize early in a typology or seek diversity in project types and delivery methods is the choice of specialization over a career as a generalist. Neither career path is fixed and both have their benefits and drawbacks. Those benefits and drawbacks are often a reflection of the individual’s capacity to proactively respond to the cyclical swings in the economy. The scope of architectural practice requires the architect to possess a vast body of knowledge that covers many different areas. Therefore, architects are generalists by training and will find most skills are readily translatable to new challenges. With desire, proper planning and mentorship, an architect may succeed in transitioning fluidly between project types by gaining the trust of various client groups and employers.

Another important consideration is whether the architect wishes to have their own practice or work for already established firms. It is important to note that this ambition can arise either early or later in a career as the right combination of life events, potential clients and resources emerges. This topic is discussed further in the section “Proprietor/Partner/Director”.

A practitioner may decide to change their jurisdiction of practice. Careful research of reciprocity agreements and licensing requirements must be undertaken prior to deciding. Reciprocity agreements for both certification and licensure exist within Canada and between Canadian and international regulatory associations. Examples include the ACE-CALA Agreements between Canada and Europe and Mutual Recognition Arrangement (MRA) between the United States and Canada. From Canadian Architect: “The Canadian Architectural Licensing Authorities (CALA) and the Architects’ Council of Europe (ACE) have confirmed the ACE-CALA Mutual Recognition Agreement for the Practice of Architecture among member states in the European Union and Canada.” (See references to agreements in chapter references.)

Mature Practitioner

As the architect gains experience and matures in their role, progressing from emerging to mature practitioner, they develop a greater self-awareness of their strengths, weaknesses, and preferences. Perhaps they have joined the leadership of a firm or have become specialized in a certain role, such as designer, building science and envelope expert, contract administrator, or production lead for construction documents. Others may decide to venture into a sole proprietorship or partnership in a small firm.

With acquired experience, they will find that they are able to give solid career advice to guide interns and emerging practitioners, either formally as mentors or informally as colleagues.

As mature practitioners, architects also play important roles in related fields at the periphery of the profession, such as expert witnesses in legal construction disputes, authors of professional publications, or participants in panels and cross-disciplinary discussions of civic, educational or other related topics. These roles draw on the experience and expertise of the mature practitioner, enhancing their profile and reputation, and ultimately represent a culmination of their work and way of thinking.

“Giving back” to the profession and the community at large can be tremendously rewarding. Mature practitioners often find satisfaction in participating on municipal design review committees or as design studio guest critics; teaching; volunteering for their provincial or territorial association’s committees; or running for political office. With years of experience in capital project planning, marketing, selling, and delivering professional services, and building relationships, a mature-career architect may be a tremendous asset to any organization.

For further discussion of legal and financial aspects of succession planning, please see Chapter 3.2 – Succession Planning.

Proprietor/Partner/Director

There are several options with variations presented to an architect who desires to assume an equity or ownership position in an architectural practice. A sole proprietor is the owner of an architectural firm. The majority of architectural firms in Canada are sole proprietorships. A partnership is formed when several architects or corporations (a partnership of corporations) join as a practice. The partnership may be an even split of the firm’s equity or a proportion of ownership based on a partnership agreement. A mature practitioner may offer a partnership position to a younger architect as a means of turning the firm’s equity into retirement savings as well as to sustain the firm’s market position and younger architect’s commitment to the practice. This chapter uses the term director to describe a variety of ownership situations in which an architect has some stake or equity position in a firm, although that may or may not relate to being in a key decision-making role. The term “principal” is often used to describe the strategic decision-makers at a firm. It may apply to a sole proprietor, partner, or director.

Typically, the percentage of ownership in the firm determines the level of strategic decision-making power an architect has. It is not uncommon for large firms to offer shares in the firm as an incentive towards performance and commitment.

Although there are many advantages to working as an employee or a leader within a large practice – shared experiences, available support, exposure to project types and locations (for example, outside the country) usually unavailable for a smaller firm – an architect may decide to establish their own practice, which can also result in tremendous professional satisfaction. Each path has its risks and rewards: ultimately this centres on an architect’s business acumen, entrepreneurial skill and desire to be the decision-maker.

It is important to note that the definition of success is ultimately personal and cannot always be quantified. Drivers for a change in role may include the desire to pursue a particular artistic direction or a passion for creating social change; the desire for a healthier work-life balance or the need to support young or aging family members; or the desire to spend time teaching and sharing knowledge with the next generation of practitioners. Another example is a sole proprietor who has ambitions to work on major projects out of their reach in terms of staffing and support, and decides to join a larger firm to do so. As such, the typical architectural career is non-linear; some architects may cycle in or out of sole proprietorship, partnership or directorship in a larger firm several times in a single career.

For more information on opening an office, please see Chapter 3.1 – Starting and Organizing an Architectural Practice.

Architect, Retired

The time may come when an architect decides to retire from the responsibilities of practice. It may be that the architect has cultivated interests and amassed the resources to pursue other activities or a new career. It may be that an architect is transitioned out of a decision-making role at a firm due to changes in ownership. An architect may find that after many years of sole proprietorship, they are unable to sell the firm and convert the firm’s equity to retirement savings. This may be a time of difficult decisions fraught with emotional upheaval. Whatever the cause of transitioning out of practice, it is essential to have a succession plan that addresses not only the financial aspects of the transition but also considers changes in life goals. (Succession planning is discussed further in this chapter. The financial aspects of succession planning are discussed in Chapter 3.2 – Succession Planning.) Additionally, there are important administrative steps to be taken in terms of relationships with professional associations, transferring of liability insurance to successors to ensure continuous coverage of legacy projects, and the housekeeping of closing out related business matters.

Depending on the jurisdiction, an architect who chooses to retire may be deemed a “Retired Member” or “Architect (Retired)” if they are in good standing and continue to pay any required annual fees. Generally, retired architects are no longer allowed to offer architectural services to the public but can keep the title “Retired Architect” and are still able to actively participate and volunteer within their association. Also, in some jurisdictions, a retired member who resigned their membership and remains in good standing can be elected as a “Life Member” by their association. Attaining this class of membership is a great honour, typically associated with a waiver of paying annual fees, amongst other benefits.

Transitions Inside and Outside of Practice

Career transitions can occur not only at points when architects change firms or pursue their desire to start their own practice but also within larger practices. It is prudent for a practice to plan in terms of internal succession planning. Individuals may be identified as having the skills to transition to more challenging roles within the firm and may be rewarded both financially and with role advancements. Such incentives help to retain key staff.

Internal transitions also occur when firms change ownership, for example when a smaller firm is bought by a larger one to enter new markets and diversify. Purchase of a firm or a merger of several firms may include architectural firms or combined architecture and engineering firms. A successful merger requires a good cultural fit between two or more organizations. Arthur Gensler warns, “Most mergers present a threat to a firm’s culture – both yours and theirs.” (Gensler, p. 21)

Succession Planning

One often overlooked aspect of retirement is succession planning. Many architectural practices cease to operate with the departure of the founder(s). Statistically, very few thrive into numerous regenerations because they did not plan for succession. Art Gensler, in his book Art’s Principles: 50 years of hard-earned lessons in building a world-class professional services firm, identifies the following roadblocks to successful succession planning:

- Ego: Leaders believe they know what’s best for the company they worked hard to establish;

- Fear of the unknown: They don’t know what to do with their lives beyond work;

- Procrastination: Leaders fail to embrace succession planning. Leaving the planning too late is often fatal to a firm.

This can be a tumultuous time for an architecture firm. A sound succession plan must address the need for finding suitable leaders and the design talent to fill the shoes of those leaving, a strategy to build and maintain trust between established clients and the incoming team, and a sound financial plan in place in order to sell one’s ownership stake upon leaving. (Many founders assume they will work forever and thus have no financial retirement plan.)

Gensler, reflecting on his own experience, advises departing leaders to undertake a “quiet transition” away from marketing and public relations, supporting the transitioning team as they become accustomed to their new responsibilities. Time should be taken as needed to allow for the new team to settle in their roles. Advising clients personally about the changes the firm is undergoing further establishes trust, as they are privy to the leadership that is being groomed and are assured that they can expect the same quality of service they have received in the past. On this topic, Gensler offers these words of wisdom:

“Ego is the main roadblock . . . It takes maturity to set aside one’s ego and think about what is best for the long-term health of the organization.”

Succession planning is not exclusively for the older architect retiring from practice. Substantial changes in personal and family goals, a changed role in practice, or a desire to change one’s career path all require a plan. In these situations, a mentor who has experienced these transitions can be invaluable to the architect. Resiliency, mentoring, job shadowing and a business continuity plan are key elements of a successful transition.

For further discussion of legal and financial aspects of succession planning, please see Chapter 3.2 – Succession Planning.

Career Transitions Outside the Practice of Architecture

Though it is beyond the scope of this chapter and best addressed by a career coach, an architect may decide for personal or professional reasons to leave the field of architecture entirely. As a generalist, the architect’s training is by its very nature broad and liberal, and an architect’s skills can translate readily to benefit a wide variety of unrelated fields that demand creativity, complex problem solving and rigour.

However, there are important legal and ethical issues to address upon leaving a career in architecture and transitioning to another. These include maintaining or transferring the liability associated with legacy projects. Each architect must review their situation with their provincial or territorial regulator to identify the specifics of their membership and areas of concern.

Mentorship and Supervision (or Management)

Role Descriptions

A discussion of roles and responsibilities in a mentoring relationship requires a common language. The terms “supervisor,” “mentor,” and “coach” are often used interchangeably both within architectural practice and in general parlance; however, these terms each have a different meaning and refer to different types of relationships. It is important that we understand how they are different and how they apply to architectural practice.

Supervisor

The term “supervisor” describes a role in a reporting relationship. A supervisor interacts with those being supervised on a regular basis, and knows the work assigned to each individual and the capabilities of the individual assigned the task. The supervisor may be the sole proprietor, a project architect, project manager or job captain. This term is often used interchangeably with “manager.” In many cases this relationship will be project-based, although in many larger firms this is not always the case.

Mentor

In architectural practice, there are two contexts in which the term “mentor” is used. The first instance is during internship. The Internship in Architecture Program requires that each intern, the mentee, recruit a member of the profession to provide guidance during their learning and practice experience. The mentor may not be the intern’s direct supervisor. The second instance refers to a more informal relationship that may be ongoing or intended for a specific event or transition. An emerging practitioner, emerging proprietor or retiring architect may be a mentee in a relationship with a mentor who can support them through a career transition.

Coach

Unlike a mentor, a coach in a professional context is focused on the development of a specific skill or a performance improvement. In architectural practice, “coaching” generally occurs within the context of either the supervisor or mentor relationship rather than as a separate dedicated relationship.

|

Mentor |

Supervisor/Manager |

Coach |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

TABLE 1 Relationships between mentors, supervisors or coaches and who they support.

Supervision/Management

Supervision is a subset of practice management. As a person who supervises (or manages) the work of another, the supervisor has direct oversight of the work being completed. The supervisor/supervised relationship is very important in architectural practice as often the supervisor is a registered professional, and thus may be legally responsible for work completed by the supervisee. This, however, is not the only reason that the supervisory relationship is important in architectural practice.

Delivering professional services involves developing relationships with other people. It relies on the intelligence, creativity, and care of talented individuals to complete great work. Architecture, like many other professions, is only as good as the people that perform it. It is therefore imperative that the architectural practice attract and retain the best and most talented interns and architects. The practice then must work diligently to help them grow and reach their maximum potential. One of the most effective ways to retain and develop staff is through the supervisor or manager’s role.

Ultimately, if the person’s role becomes misaligned with their goals, it can lead to staff searching for other opportunities. This is both expensive and unproductive for the firm.

Best Practices

Given the importance of supervision as one transitions into roles that require the management of others, the manager should strive to become effective at building relationships. Resources to support the development of managerial skills and capabilities can be obtained thorough continuing education opportunities offered by many universities, colleges, and professional associations. This section explores some high-level strategies and general behaviours that can be effective in architectural practice.

Most importantly, as a manager, a relationship with the people being supervised is critical. This requires a solid understanding of employees’ capabilities, goals, and desires for learning, growth, and advancement. Without understanding each person’s goals and priorities, a manager will struggle to assist in their professional growth or may assign tasks that are not appropriately challenging and rewarding.

One of the most highly recognized techniques for developing this professional relationship is the one-on-one meeting. This is a regularly scheduled meeting between supervisor and supervisee, where the primary focus is the communication and trust development between the two parties. This meeting has been shown to be very effective across a broad range of workplaces, and particularly in professional services firms.

Another important element of supervision is feedback. In architectural practice, much work relies on judgement informed by experience. There is often more than one “correct” answer to a problem, and many ways to approach a design challenge. Because of the bespoke nature of architectural work, it is critical to give the team members regular, constructive feedback on their performance. People require constructive feedback. Even corrective feedback is valuable if delivered thoughtfully, constructively, and respectfully. If feedback is not provided, there cannot be a reasonable expectation of performance improvement. Clear expectations, achievable goals, positive reinforcement for a job well done, and rewards when team members have exceeded expectations promote stronger team unity and improved performance.

A supervisor also has the responsibility to support employees’ development into professionals. The supervisor is not primarily responsible for professional development, as that lies with the individual team member, but to the fullest extent possible the supervisor should assist with this process, sometimes in the role of coach.

Where feedback is about giving timely direction on performance, coaching can be a longer-term commitment to helping develop a skill of a team member. An example of this might be assisting in developing an employee’s skills in client relationship management, particularly if the employee struggles with relationship building. The supervisor helps the team member to develop a plan for expanding their skill set and to look for opportunities to practise in a safe, non-threatening environment, such as an internal presentation to other people in the firm. As coaching can be a significant investment by the supervisor, it is advisable to set clear goals and timelines around the development effort, and to monitor progress carefully. While it is an investment, helping team members reach their potential can pay significant dividends for the firm.

Another way to help team members develop is through delegation of responsibilities. Delegation can be challenging as it requires the supervisor to “let go” of certain responsibilities and trust that training and support have provided the employee with the skill set needed to execute the tasks proficiently. Delegating work to the team can help them grow as professionals and can free the supervisor for other high-value tasks.

Ultimately, as a manager/supervisor, your role is to help the firm attract and retain the most talented professionals and to deliver results for the practice. Effective supervision is critical to the ongoing success of an architectural practice.

Mentorship for Licensure

Most architectural professionals first encounter mentorship within the context of their jurisdiction’s internship in architecture program. The purpose of these programs is to “provide interns with a structured transition between formal education and architectural registration” (AIA: Mentoring Essentials for IDP Supervisors and Mentors, p.2). In most jurisdictions, it is advised that the mentor be from a different practice than the mentee. This is to avoid the mentor being placed in a situation where there is a real or perceived conflict of interest between the needs and desires of the intern and that of the practice. It also allows the mentor to observe the internship from the “outside” and give objective advice on professional development to the intern. If it is unavoidable that the mentor and mentee are from the same practice, it is strongly advised that the mentor is not also the mentee’s supervisor. The two roles are very different, and in some instances these roles might conflict.

Usually, the mentor is a practising architect, although there are some jurisdictions where retired practitioners are allowed.

In the context of an internship, the mentoring relationship is focused on the development of the intern towards a specific goal: licensure. As such, this relationship is generally structured around periodic one-on-one meetings where mentor and mentee will review the intern’s activities from the given period and discuss areas for development. It is advisable that these meetings be scheduled regularly in advance, rather than requested on an as-needed basis, to ensure the momentum of development continues. It is the mentee’s responsibility to set up and run these meetings. The mentor’s role is that of an advisor: someone who gives an appraisal of the intern’s progress and helps them formulate a vision for their future development within the internship program.

Mentorship for Practising Professionals

While mentorship is a fundamental component of the many jurisdictions’ professional accreditation process in Canada, mentorship continues to be valuable throughout our professional careers.

A mentor is someone who primarily is guiding your professional growth. This relationship is about the longer term and broader goals. In architectural practice this is usually a relationship with a more experienced colleague. It is generally recommended that the mentor be from outside the mentee’s organization, but in some rare instances this is neither possible nor desirable. Face-to-face meetings with a mentor might happen every couple of months, and phone calls or email exchanges could happen more frequently if desired by both parties. There are different types of mentors, but generally the relationship forms around developing one aspect of the professional skill set. Throughout one’s career, one might have several different mentors at different times, each focusing on different aspects of professional development.

An example of a mentor/mentee relationship that varies from the obvious younger apprentice learning from the older journeyman, is the digital native employee supporting the learning of the senior principal in building information modeling, new processes in integrated practice, and the use of ever evolving software applications.

As a rule, the mentor/mentee relationship should be initiated by the mentee. The mentee should carefully consider which skills they wish to develop, and then actively seek out a mentor who has specific knowledge of these skills. If the mentee does not know of someone appropriate, the supervisor or other practice leader may be able to provide guidance. When making the request of the mentor, it is generally recommended that the mentee make the parameters of the mentorship explicit. This means being specific about both what they hope to gain from the mentorship as well as the anticipated time commitment from the mentor. As mentor candidates are often senior professionals, they may have many responsibilities to their own firm, and their time is at a premium. One approach that can be effective is setting an “expiry” date on the mentorship – a timeframe within which it would be reasonable to achieve the development one is seeking. In this way, the mentor is not being asked for an indefinite commitment and may be more likely to accept the role.

The benefits of effective mentorship to the mentee are obvious, but there are benefits for both the mentor and the mentee’s practice as well. For the mentor, they have an opportunity to share their professional knowledge and contribute to the future of architectural practice. Through this relationship, they may also gain a better understanding of the challenges faced by younger staff at their own firm. Mentors get a chance to develop their leadership skills, which may assist them in making their own transition to practice leadership. Another aspect that cannot be overlooked is that it is often an honour to be asked by an up-and-coming architect to be their mentor – it means your work as a professional is respected by them and you are looked up to for advice.

Firms benefit from the mentees gaining a broader understanding of the profession outside of their particular practice and developing their professional network. Working with an external mentor also provides the opportunity for the mentee to bring new ideas around professional practice to the firm.

|

Benefits for the mentor |

Benefits for the mentee |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Benefits for both |

|---|

|

TABLE 2 Mentor/mentee relationship benefits.

Mentorship provides significant value to all parties throughout all phases of a professional career, and it is advised that practising professionals seek out opportunities to mentor and be mentored. This sharing of knowledge can only strengthen our professional practice as a whole.

References

Mentoring Essentials for IDP Supervisors and Mentors. American Institute of Architects, November 2012.

“Mentorship and Sponsorship.” American Institute of Architects, 2019, http://content.aia.org/sites/default/files/2019-06/AIA_Guides_for_Equitable_Practice_06_Mentorship_Sponsorship.pdf, accessed April 21, 2020.

“Internship in Architecture Program.” Canadian Architectural Licensing Authorities, 4th Edition, January 2012, https://raic.org/sites/raic.org/files/pub_resources/documents/iap_e.pdf, accessed April 21, 2020.

Drucker, Peter. The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done. Harper Collins, 2015.

Gensler, Art and Lindenmayer, Michael. Art’s Principles: 50 years of hard-earned lessons in building a world-class professional services firm. Wilson Lafferty, 2015.

Gingras, Pierre-Paul, Bourdeau, Laurent. Rencontre avec un mentor. Montréal: JFD Éditions, 2013.

“Mentoring and essential skills.” Employment and Social Development Canada, https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/essential-skills/tools/mentoring.html, accessed April 21, 2020.

Horstman, Mark. The Effective Manager. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2016.

“Canada.” National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB), https://www.ncarb.org/advance-your-career/international-practice/canada, accessed April 21, 2020.

“Intern Architect.” Ontario Association of Architects, https://oaa.on.ca/registration-licensing/intern-architect, accessed September 11, 2020.

Sgroi, C.A., Ryniker, M. “Preparing for the Real World: A Prelude to a Fieldwork Experience.” Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 13(1), 2002, 187-200.

Stone, D. Mastering the Business of Architecture. Ontario Association of Architects, Toronto, 2004.

Verma, V.J. The Human Aspect of Project Management, Volume Two, Human Resource Skills for the Project Manager. Newtown Square, Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute, 1996.

Verma, V.J. The Human Aspect of Project Management, Volume Three, Managing the Project Team. Newtown Square, Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute, 1996.

Zachary, Louis. The Mentor’s Guide: Facilitating Effective Learning Relationships. 2nd Edition. San Francisco: Jose-Boss, 2013.