Definitions

Communication: The science and practice of transmitting information; the act of imparting news; information given; social dealings.

Stakeholders: Any person or group of people who may impact outcomes or be impacted by project outcomes.

Introduction

One of the greatest challenges in achieving successful project outcomes is managing the demands of project stakeholders while working to meet the owner’s requirements of scope, quality, schedule, and budget. The management of a project’s requirements and the management of its stakeholders are integrally linked. This is particularly true for complex projects that have an extensive and complicated functional program involving multiple stakeholder groups with competing interests.

As there are many stakeholders and stakeholder groups involved in projects, large and small, stakeholder engagement is best managed not solely by the client but collaboratively by all of those in a project leadership role. The client and the architect both play important and potentially different parts in engaging and communicating with stakeholders, and should discuss, in explicit terms, their desired outcomes and the role and responsibilities that each has in stakeholder management.

This chapter is intended to guide the architect in establishing and maintaining efficient and effective project management practices while managing the relationships among those who have an impact on project outcomes and/or will be impacted by project outcomes. It provides clear direction on the use of project management principles and methodologies in order to manage the project’s stakeholders. It outlines techniques for analyzing stakeholders’ interests and influences, and proposes specific processes for monitoring stakeholder engagement.

The importance of stakeholder management and the soft skills required to build relationships can best be stated in this paraphrased comment:

A client may not remember how much a project was over budget or behind schedule, but they will always remember how you made them feel.

Sean Rodrigues, FRAIC

The Rise of Stakeholder Influence in Design Projects

In 1984, Dr. F. Edward Freeman outlined a new theory in his book Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Freeman’s “Stakeholder Theory” represented a significant departure from the traditional approach to managing relationships with those that could have an impact on a business’s strategic objectives. Up to that time, the thinking of early 20th century economist Milton Friedman was widely acknowledged: the only stakeholder of concern to a business is the shareholder. Freeman’s “Stakeholder Theory” introduced the notion that anyone who could influence a business’s strategic objectives was a stakeholder. This concept has now been widely accepted in strategic, organizational and project management.

We can witness the growth in importance of stakeholder management over the past 25 years by analyzing the changes to the Project Management Institute’s A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide) from the Exposure Draft released in 1994 to the Sixth Edition published in 2017. Project management was originally conceived as sets of processes that, if executed correctly and in order, would result in project success. In the Exposure Draft, there was scant information about stakeholders. A brief mention in the Communications Management section states: “The information needs of various stakeholders should be analyzed to develop a methodical and logical view of their information needs . . . Provide all information needed for project success . . . Without wasting resources on unnecessary information . . .”. Through successive editions, the role that stakeholders’ interests and influences played in project success became increasingly important. In the 2013 Fifth Edition, a new knowledge area was added, Stakeholder Management. The role of the project manager has changed from being an expert in planning and executing structured processes to that of negotiating the sometimes mystifying world of human emotion, interests and power dynamics. The Project Management Institute now considers interpersonal skills and leadership ability to be foundational for the effective project manager.

Design projects have become increasingly complex. Site plan approval processes in major cities can now take many months or years, and can require multiple schemes to satisfy stakeholders’ interests. The rise in stakeholders’ influence has resulted from concerns for the environment, complex functional programs, the increased number of built environment specialists, branded certifications such as LEED and WELL, a drive toward risk transfer, and a desire for increased building performance through less adversarial relationships and increased collaboration.

Project Stakeholders

There are many definitions of project stakeholders; however, for the purposes of this discussion, the definition adapted from Nutt and Backoff is best suited for the project environment:

All parties who will be affected by or will affect the project’s outcome. (439)

Therefore, project stakeholders are any individuals or groups that may affect project outcomes or may be affected by project outcomes. Stakeholders include:

- Client or owner:

- owner’s representative (project sponsor or key project decision-maker);

- owner’s project manager;

- various departments in the owner’s organization responsible for financials, resources and accountability, facility operations and maintenance, etc.;

- shareholders or board of directors;

- owner’s employees or tenants (user stakeholders).

- Design team:

- principals of architecture and consulting engineering firms;

- project architect and project engineers;

- design, production and contract administration staff;

- firms’ operational staff including human resources, financial management, and technology systems;

- professional liability insurers and other support organizations;

- specialized consultants (building code, acoustics, accessibility, etc.).

- Construction team:

- general contractor, construction manager, or design-builder firm owner(s) and owners of subtrade firms;

- office staff;

- site workers;

- manufacturers and distributors of building products.

- Authorities having jurisdiction:

- municipal and conservation area planning and design review panel members;

- building department employees, including plans examiners and site inspectors;

- health and safety authorities;

- elected officials;

- federal, provincial, territorial, and First Nations departments and agencies with regulation enforcement responsibilities and authority.

- Certification agencies:

- Canada Green Building Council (CaGBC) and Green Business Certification Inc. (GBCI);

- LEED;

- BOMA.

- General public:

- neighbours;

- specific interest groups.

The list of stakeholders could be very long. Stakeholders will have varying degrees of interest in project success and/or the power or influence to affect project outcomes. Conversely, stakeholders may also have an interest, the power, or both, to negatively affect project outcomes.

Stakeholder Management Processes

The management of project stakeholders involves three processes:

- Identifying and analyzing stakeholders;

- Planning stakeholder engagement through developing strategies that respond to their interest in the project and their ability to influence project outcomes; and

- Managing and monitoring stakeholder engagement.

Stakeholder Identification and Analysis

The identification of stakeholders is pivotal to project success. A project risk of omitting to identify stakeholders at the project’s outset has the potential for a high negative impact on outcomes. However, doing this at the beginning of a project is difficult. A proactive approach that utilizes various tools and techniques will mitigate one of a project’s most significant risks: unstated stakeholder requirements. These can lead to scope creep, unforeseen costs and user dissatisfaction, among other potential consequences. Multiple tools and techniques are available, including producing a stakeholder breakdown structure. This is a structured and hierarchical representation of generic stakeholders’ roles relevant to design projects. It provides a prompt for stakeholder identification for a specific project.

The output of this process is the creation of a stakeholder register. The stakeholder register lists all stakeholders, their names and contact information, interest in the project, their ability to influence outcomes, and, as the register is further developed in the next process, the strategy for engaging each stakeholder. The register is a living document and is revised on an ongoing basis as more stakeholders are identified over the course of the project.

Brainstorming and mind mapping tools may be used to identify and categorize as many stakeholders as possible during an initial planning session. If the name of the stakeholder cannot be identified, then a placeholder should be included in the stakeholder registry, and later modified to add a specific person or people.

There can be many stakeholders involved in a project, and there are numerous approaches to managing their engagement. An architect requires both communication and interpersonal skills to motivate stakeholders to support project objectives. Put simply, stakeholder analysis involves identifying where a stakeholder is on the spectrum of project support – at the one end actively supporting the project, and at the other, actively opposing it – and then moving the stakeholder towards the desired position.

The two key factors in analyzing stakeholders are their interest in the project and their influence or power to impact project outcomes. For example, in the design of a school, teachers may have high interest in the design but low influence with a budget-focused administration. A municipal planning committee may have the power to delay a project’s approval but limited interest in the project as it does not contribute to their larger urban planning goals. A hospital vice president may have a high level of both interest and influence in the design of a renovated emergency department intended to reduce patient waiting times. A strategy to motivate each of these different stakeholders to commit to project objectives is required.

There are a host of tools available to map the interests, influence, relationships, participation, responsibilities, and requirements of project stakeholders. Two variations of a matrix that illustrate the relationship between a stakeholder and their commitment to a project are the Stakeholder Engagement Assessment Matrix (PMBOK Guide) and the Power/Interest Matrix (Johnson, et.al., 2005) . Both matrices categorize identified stakeholders based on their position on a spectrum of project commitments: actively supporting project interests on one end, to actively opposing project interests on the other. Both tools have been adapted and altered over time to meet the needs of different industries. The purpose of both tools is to aid the project team in developing strategies to manage stakeholder engagement.

Stakeholder Engagement Assessment Matrix

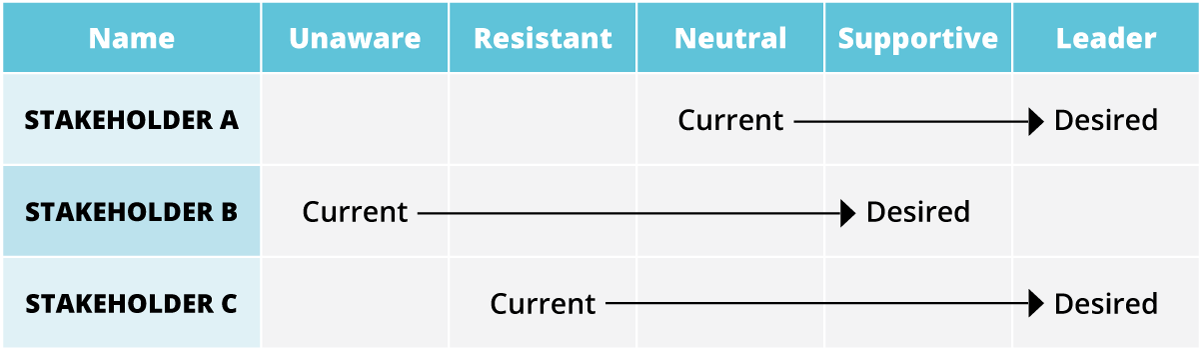

TABLE 1 Stakeholder Engagement Assessment Matrix. Project Management Institute Inc., A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 2017. Copyright and all rights reserved. Material from this publication has been reproduced with the permission of PMI.

The Stakeholder Engagement Assessment Matrix from the Project Management Institute’s A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Sixth Edition identifies the current state of the stakeholders’ attitudes towards project objectives and the project manager’s desired state. Proactive analysis of stakeholders’ attitudes permits a plan of action to be developed that will support project objectives, rather than ad hoc relationship management.

This tool may be used by a project team during an interactive session to develop strategies for getting some stakeholders onside, or at least for determining how to ensure they do not interfere with project outcomes.

Stakeholder Interest/Influence Matrix

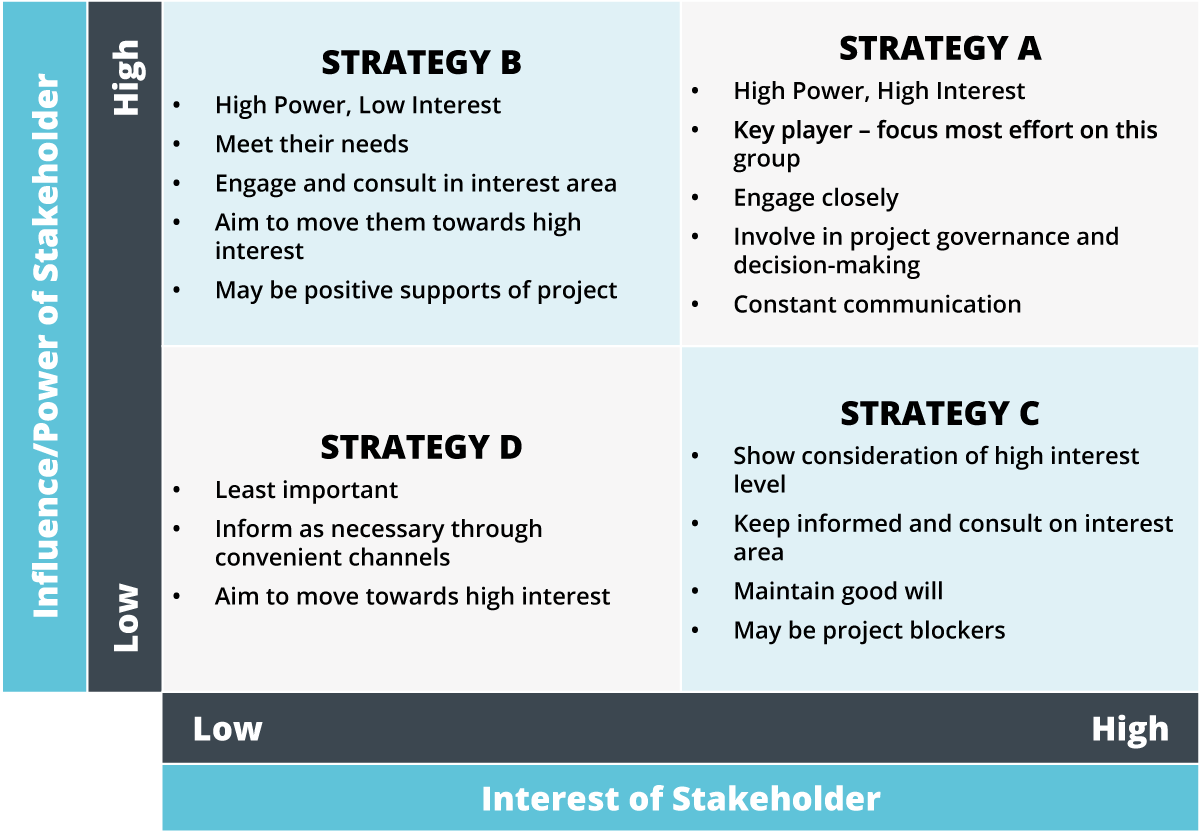

FIGURE 1 Power/Interest Matrix, (Johnson. et.al, 2005)

There are many variations of the power/interest or influence/interest matrices. The simplest of these is a 2x2 grid with interest in the project on one axis and power to influence the project outcomes on the other. The intent of the grid is to group stakeholders so that the most efficient and effective strategies for managing their engagement can be applied. The grouping of stakeholders supports optimal and selective communication messaging through the most appropriate medium to each group. Again, the tool can be used during a team’s interactive project planning session to identify stakeholders’ communication and engagement needs.

The work of analyzing stakeholders provides an input to the stakeholder management plan that the entire project team can execute to proactively build project commitment.

Planning Stakeholder Engagement

The stakeholder engagement plan takes the analysis of stakeholder attitudes, interests and influence and describes a planned approach of how stakeholders will be engaged and communications managed. The stakeholder engagement plan is closely aligned with the communication management plan. See Chapter 5.3 – Communications Management.

A stakeholder engagement plan describes:

- realistic expectations of stakeholders;

- the resources that need to be applied to the process of managing stakeholder engagement, including human and financial resources;

- the planned interactions, including meetings, retreats, social events and one-on-one opportunities built into the project schedule;

- information needs of each stakeholder, including:

- content of communications, such as project updates on completed scope, budget and schedule status, and achieved target;

- frequency of communication;

- mode of communication, including technology.

Managing and Monitoring Stakeholder Engagement

Maintaining stakeholder engagement is an ongoing process throughout the life cycle of the design, construction and operational program. Many traditional architectural practices are in place for managing stakeholder engagement, including regular meetings with client representatives, user information gathering sessions, construction project kick-off meetings and routine site meetings. Maintaining stakeholder engagement requires executing the project’s stakeholder engagement plan and the communication plan, and routinely monitoring communications to ensure that the intended audiences are receiving, through the most accessible and appropriate technologies, the crafted messages when needed, in the format required, while employing interpersonal skills and political awareness. Again, see Chapter 5.3 – Communications Management.

Project Politics and Political Awareness

“Everything would be going fantastic if we could just eliminate the politics!” This is an often-heard refrain from those trying to move a project ahead in the face of opposition or indifference but who have limited power to do so. Politics is neither good nor bad but simply the way that people influence others in order to achieve their objectives. Project politics is an inevitable circumstance that the project architect must address and use to their advantage. In the broadest terms, bad politics focus on “I” while good politics focus on “we.”

The subject of politics will exist in the architectural office, the design team, the client organization, and the general public. Political awareness, like the interpersonal skills of leadership, negotiation and conflict management, is required of the project architect to build commitment to project objectives. At the heart of political influence is building networks. The architect does this by:

- motivating and rewarding design team members for their performance;

- building a bank account of influence by supporting their network;

- exercising informal power;

- developing strategies for acquiring, using and maintaining power.

For a comprehensive discussion of political awareness and the strategies and tools for influencing others in a project environment, the reader is advised to refer to Vijay Verma’s The Art of Positive Politics: A Key to Delivering Successful Projects.

References

Johnson, G., Scholes, K. and Whittington, R., Exploring Corporate Strategy: Text and Cases, 7th edition, London: Prentice Hall, 2005.

Nguyen, Giang Thi. Key Stakeholders’ Impacts on the Implementation Phase of International Development Projects: Case Studies, 2010, accessed July 14, 2020 from https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:292139/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

Nutt, P.C., and R.W. Backoff. Strategic Management of Public and Third Sector Organizations: A Handbook for Leaders. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1992.

Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Sixth Edition. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2017.

Trentim, Mario Henrique. Managing Stakeholders as Clients. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2013.

Verma, Vijay. The Art of Positive Politics: A Key to Delivering Successful Projects. Oshawa, ON: Multi-Media Publications Inc., 2018.

Verma, Vijay. The Human Aspects of Project Management, Volume One: Organizing Projects for Success. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 1995.