Introduction

In the construction industry, the term “specifications” generally means a clearly written description of the intended work of a project. Specifications are precise descriptions of products, materials, standards, equipment, services, construction systems, construction methods and processes, and workmanship. In the simplest terms, drawings show what, where and how many, while specifications show what it is, what its qualities/standards are, and how it is installed.

Specifications also describe physical and environmental conditions to be created and maintained in the work area, on site, in adjacent areas, or off site. In addition, the specifications set out procedures for contract administration required to control and monitor the quality of the work.

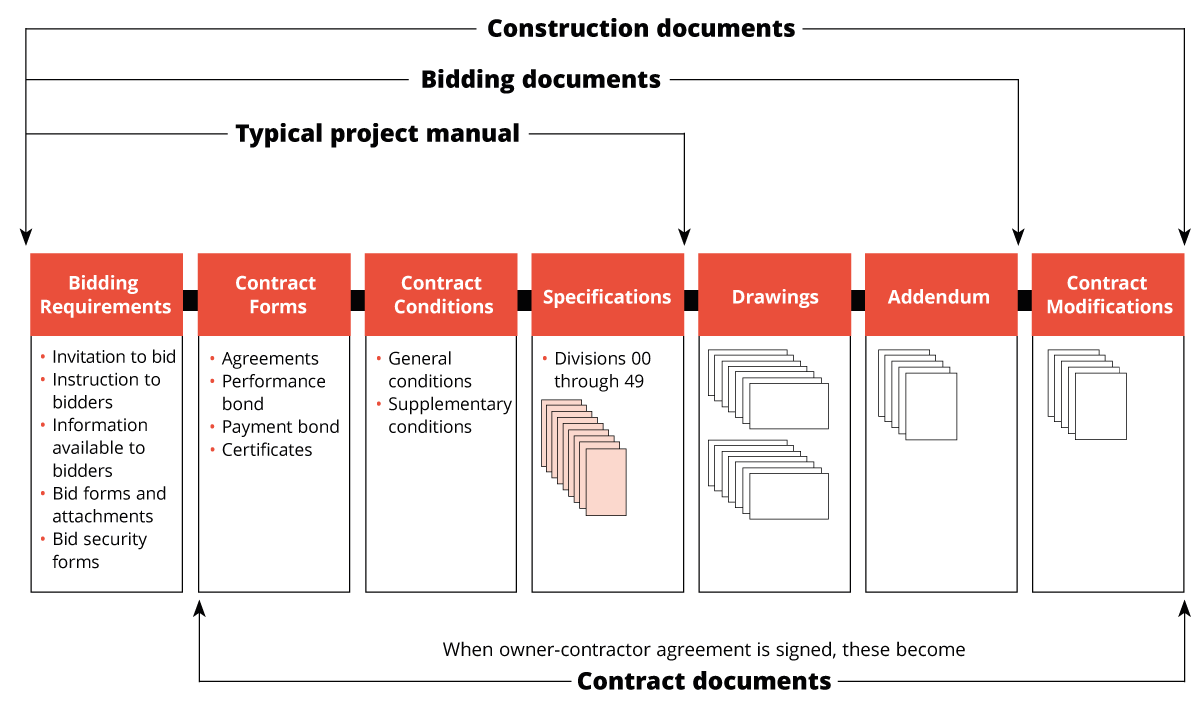

FIGURE 1 Format for Construction Documents

Purpose of Specifications

Specifications and drawings are companion documents. Specifications provide information complementary to drawings that is necessary for a complete definition of the obligations of contractors under the construction contract. They address issues that are best expressed in written form.

Specifications define the general and trade contractors’ responsibilities and obligations for products and materials used and for the procedures, general means and methods to be used in the execution of the work. They also prescribe the conditions of acceptance of the work performed.

Specifications are meant to address:

- Division 01 of most specifications: general requirements applicable to the organization and performance of construction work, including:

- roles, responsibilities and specific duties and procedures relative to contract administration;

- general contractor or construction manager’s obligations;

- contractors’ roles and responsibilities regarding construction site organization, temporary work and related requirements that will not be integrated into or form part of the completed building;

- overarching requirements governing the performance of construction work in terms of materials, products and workmanship quality requirements, sustainable development considerations, etc.

- Technical divisions (02 and thereafter): technical requirements specific to the various parts of the work described in the drawings, involving various trades or types of building materials, systems and technologies, structured as separate “sections” for each, including:

- the application of Division 01 requirements;

- detailed information regarding the types, performance characteristics, physical properties and technical features of base materials, construction products or systems with the associated reference standards applicable;

- requirements applicable to workmanship, work procedures, means and methods prior to, during and at completion of the work;

- where necessary and convenient, schedules, illustrations, or any additional information which is more convenient to insert within the specifications binder than to feature in the drawings.

Specifications are usually produced and presented in a standard paper-sized binder separate from the drawing set. In the case of some small projects or when aimed at work involving a single trade, specifications may be inserted among the drawings, usually in a single, all-text sheet; however, it is important that minimum standards of practice are maintained, and applicable general and technical requirements are included.

Types of Specifications

Specifications are either “prescriptive” or “performance,” or a combination of both.

Prescriptive specifications detail the expected components and applicable reference standards for a material or system and may include specific material and system options (“choose from a, b or c”) that are pre-approved for use because they are deemed to meet the prescribed criteria. Prescriptive specifications serve both to direct contractors in the selection of materials and products to use and workmanship practices to observe, and as quality control direct reference tools for architects while performing construction contract administration services.

Performance specifications describe the performance expectations of materials and systems without necessarily naming products that meet those expectations. They are generally used where the application of conventional, well-established construction industry performance standards and practices will produce the results required by a building’s intended uses or technical performance requirements. They allow more latitude and discretion for contractors in the choice of materials, products or workmanship means and methods to be used in the execution of the work. Performance specifications may allow bidders and contractors to more easily introduce innovative or more cost-effective or economical solutions, possibly procuring the client better value against costs. Performance specifications also imply that the final details of construction solutions to be incorporated in the building will be developed by contractors, systems or products manufacturers or subcontractors, with the architect and client using the submittal review process to confirm conformity to performance requirements stated in the specifications. Performance specs may require as much up-front effort as prescriptive specs to create them and will require more effort to review the contractor’s selections.

The type of specifications to develop for the building’s construction should be determined in advance to be consistent with:

- the project’s chosen delivery method and/or construction contract procurement strategies;

- the client’s and/or architect’s level of quality control over the work performed and delivered.

Some public sector clients, such as Canada’s federal government, may require as a matter of policy that all specifications be of the prescriptive type, regardless of the type of work involved. Private sector clients are usually more receptive to performance specifications and may even direct architects to use this type systematically in order to benefit as much as possible from market competition. In most project instances, notwithstanding client policies, the nature of the project will likely call for specifications to include both prescriptive and performance information.

The development and production of specifications can be approached from several perspectives and methodologies. The context of the project predicates what methods are best suited, and architects must exercise judgement in this respect.

Methods of Specifying

Contemporary construction specifications are normally prepared using either or both of the following descriptive methods:

- proprietary (describes specific products and systems by trade name);

- generic (describes materials’ and products’ physical characteristics and properties or systems, as well as workmanship and practice standards).

Project delivery methods, procurement models and client policies regarding competitive bidding will influence which method or combinations of methods are best suited to the work.

Public sector clients, such as Canada’s federal government, may require, as a matter of policy or as related to laws or regulations on commerce (for example: trade agreements), that all specifications be prepared in accordance with the generic method type regardless of the type of specifications used (prescriptive or performance). They may be compelled to disallow proprietary specifications except under highly specific circumstances, such as where:

- only one specific material will fulfill the exact requirements of the project;

- specific materials are required to match existing materials;

- the project has an unusual function or timing requirement, such as emergency repairs.

Private sector clients have more flexibility to use either method or both in combination.

The key to deciding what combinations of prescriptive or performance and generic or proprietary specifications to use may lie with considering who, among the client, the designers or the contractor, is in the most effective position to contribute to the project to achieve best value. Factors that may affect specifications type include:

- initial capital cost;

- operating cost;

- sustainability values;

- aesthetic value, etc.

For relatively standard and straightforward projects, architects often prefer the proprietary method to embed their own product experience into construction detail designs. Materials and products are specified based on the architect’s experience of the interfaces and interactions of materials in a design, including performance and quality reliability as well as of effective technical support during the design and construction stage. This performance experience is valuable to clients, provided that it does not inappropriately restrict market-driven competition and innovation and that it does not create conditions that reduce contractors’ liabilities and responsibilities towards achieving results that conform to building elements’ fitness for purpose.

Proprietary Method

Proprietary specifications identify products by their trade names and important characteristics and, preferably, use the manufacturers’ exact catalogue names and descriptions to avoid any ambiguities.

The proprietary method of specifications may be appropriate or even necessary under various project-driven circumstances such as design considerations and client considerations.

Design considerations may include:

- compliance with governing building codes and regulations, municipal urban planning regulations and bylaws, building permit conditions, etc.;

- building durability and life cycle requirements;

- environmentally sustainable construction;

- workplace environmental performance requirements;

- heritage conservation programs, etc.;

- sole-sourced or innovative products or materials that are inherent parts of design solutions or detailing;

- product matching in existing building renovations, remodeling, or rehabilitation projects where existing materials and products are to be conserved and reused or to ensure compatibility between new and existing materials where they must be mutually integrated;

- requirements of professional practice regulations.

Client considerations may include:

- exercising authority and discretion so that material or product or system selection will be compatible with:

- pre-existing supply arrangements for specific materials or products or pre-qualified product listings;

- pre-existing building operations and maintenance procedures and practice standards, in projects that are repeat instances of existing buildings, to assure repeatability of results previously achieved.

Proprietary specifications may involve:

- restricted materials or products designations, either sole-source or within a specific list limiting list of materials, products, or manufacturers;

- “open” designation of materials or products identified as “acceptable” strictly for “indicative” purposes, as references for contractor selection and submittals for approval of products and materials contemplated. Single references are often adequate for some elements but a listing of three to five such references is usually preferable to cover minor variances between products that do not affect their suitability to contract requirements.

All products listed should be true equivalents of one another. All products listed are also to be qualified by the expression “or approved alternative” or similar wording, referring to contract procedures regarding submittal and approval of substitutions.

The wording of proprietary specifications should include provision for the review of proposed alternatives using submittal procedures consistent with Division 01 of the specifications and the construction agreement (sometimes these two documents say somewhat different things). It is important for architects to be familiar with this contractual framework so as to formulate the specifications accordingly. Specifying compliance with the unique characteristics of one product should not be done to create a proprietary specification that masquerades as a generic specification.

Generic Method

Generic specifications describe the requirements applicable to materials, products, or systems in terms of physical characteristics and properties or performance characteristics. Performance criteria may include characteristics and requirements such as appearance, strength and durability. When a detailed description of the product is accompanied by a performance statement, then the contractor is clearly responsible for the end-product. To achieve the best results, the architect should remember that performance is the prime factor. Prescriptive generic specifications require in-depth research by the architect.

Example: .1 Windows: to CAN/CSA - A440 [M90]

- Type: Projected: top projected with triple glazing

- Classification Rating

- Air Tightness: A3

- Water Tightness: B5

- Wind Load Resistance: C2

- Condensation Resistance: Temp Index [ ]

Here, the specifier chooses to describe what is needed to comply with the requirements of the project, rather than describing how it is to be built to ensure its required performance. When a component is required to comply with testing procedures, that is, in effect, a performance specification.

It is important when defining performance criteria applicable to generic descriptions to:

- ensure that the desired outcome cannot be delivered without the performance specified being achieved;

- ensure that whether the required level of performance has been achieved (i.e., wherever possible the specification should be objective, not subjective), it can be objectively field-tested, preferably in accordance with standardized test methods, and where such methods are available and relevant, they must be indicated as references applicable to quality control of the work;

- require evidence of compliance with the specification (manufacturers’ test results, calculations, records of tests, provision of samples and mock-ups, etc.);

- ensure that tests and compliance requirements are economically practicable and commensurate to the critical importance of building elements involved with respect to key building performance criteria;

- ensure where there are elements of prescriptive and performance specification that performance items can be properly integrated into the rest of the work.

Reference Standards

Specifications frequently incorporate references to standards published by standards organizations and trade associations. Well-written standards allow some latitude in the means of achieving the desired result, while establishing industry-accepted standards of practice and performance. Provided they are fully familiar with the latest edition of the standards, architects may choose to incorporate some of them, by reference, into the specifications.

References include publications from standards writing bodies such as CSA, ULC, CGSB and ASTM, or appropriate trade manuals to define common criteria. Such trade manuals are produced by several national trade associations, such as:

- the Architectural Woodwork Manufacturers Association of Canada (AWMAC);

- the Canadian Roofing Contractors Association (CRCA);

- the Terrazzo Tile & Marble Association of Canada (TTMAC).

The use of such standards and manuals will reduce the volume of the specifications to a considerable degree.

Where a standard is referenced, the specifier or architect normally verifies that the number is correct, together with the date of the latest issue of the standard or code. If the standard has been amended, the specifier or architect may confirm that the amendments have not changed any significant criteria that would affect the types and uses of the product or procedure.

The globalization of trade, as well as specific bilateral or trilateral trade agreements such as between Canada, the United States and Mexico, and Canada and the EU, may give rise to confusing situations where, for example, the same product name and number manufactured by the same company, but in different countries, is actually fabricated to differing standards in the country of fabrication, then shipped to the country of the project without the architect (and often without the contractor) being made aware that the product supplied has actually been tested to a different standard than the specified standard. It is incumbent on the architect, as part of the submittal review process, to ascertain that the performance standards identified in the specifications are satisfied by the actual products supplied.

See Chapter 6.6 – Construction Contract Administration – Office and Field Functions.

See Chapter 2.5 – Standards Organizations, Certification and Testing Agencies, and Trade Associations.

MasterFormat

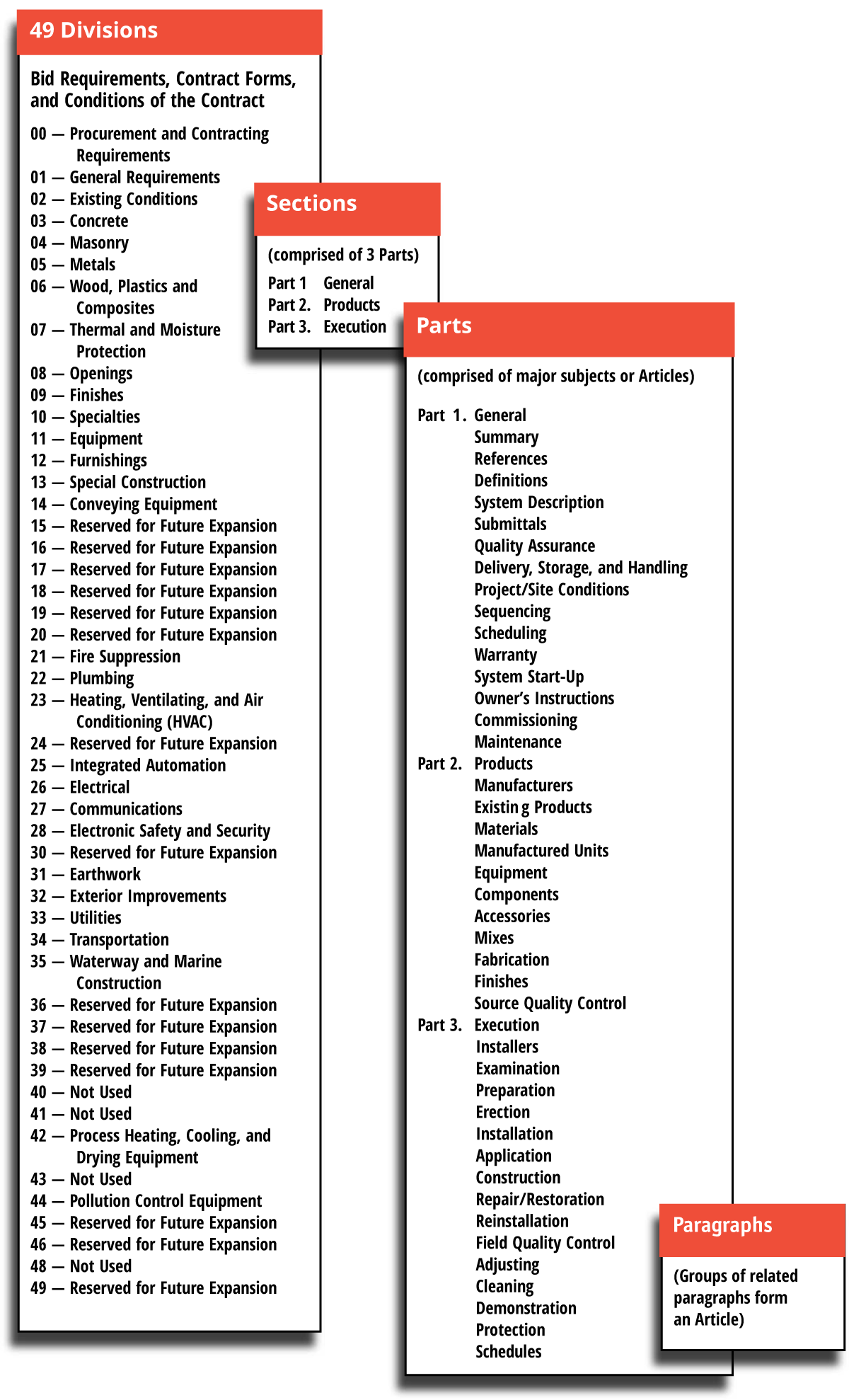

MasterFormat™ is a system of numbers and titles for organizing construction information into a regular standard order or sequence. It is organized into a 48-division specification format, using a six-digit section numbering system. Each section is, in turn, organized according to a three-part format for articles titled: General, Products and Execution. In addition to the 48 divisions and their groups of sections, MasterFormat contains what has become known as the Series 00 of documents, which incorporates an organizational structure for documentary information for the project manual.

The primary purpose of the MasterFormat system is to provide a method to:

- organize information contained in project specifications;

- retrieve all files, costs, product literature, references and parts of project specifications from a single unified system.

Of the manuals for this purpose, MasterFormat Numbers & Titles is one of the most widely used. Since 1978, MasterFormat has been produced jointly by the Construction Specifications Institute (U.S.A.) and Construction Specifications Canada. Initially conceived in 1963, it has been almost unanimously accepted by the construction industry in the United States and Canada.

Under Division 00 “Procurement and Contracting Requirements,” the following is included:

- bidding information, forms and requirements;

- contract forms and bond requirements;

- general and supplementary conditions of the contract.

Under Division 01 “General Requirements,” the following is included:

- general requirements;

- summary description of the work;

- price and payment procedures;

- administrative requirements;

- quality requirements;

- temporary facilities and controls;

- product requirements;

- execution and closeout requirements;

- performance requirements;

- life cycle activities.

Architects should address Division 01 requirements early in the development of construction documents, as a number of issues addressed in the various sections directly affect the scope and organization of the construction drawings and specifications by setting the overarching context under which construction work is to be organized, executed and monitored.

The designation system for the headings for these groupings has been included to standardize the titles, and to allow for the storage, search, edit and retrieval of the various elements. Titles and terminology should be fixed and used in the sequence shown. Any number of additional entries may be inserted by decimal expansion, if required.

FIGURE 2: Diagram Illustrating the Framework of the MasterFormat System

Note that some titles will be unnecessary under certain methods of construction procurement. For example, bidding information will not be required when the owner is the builder.

The MasterFormat system:

- provides a flexible system within a standard framework for fixed sections;

- is adaptable to computer word-processing software;

- allows the user to decide whether to use fixed or flexible section titles;

- allows each subject or component to be easily located with the designated six-digit number through use of the guide.

Using standard titles and numbers results in a higher degree of uniformity within construction specifications. The section titles, given in the index, should be used for either a fixed or a flexible system, using the wording and sequence proposed.

The 48 divisions are titles only, contain no text, and are listed in the table of contents of the specification as a means to search for information contained in sections which are grouped and listed under the heading of that division.

Example:

Division 04. Masonry: Section 04 21 13 — Brick Masonry

Every practising architect should use MasterFormat for producing project specifications and as a basis for an office technical library, for organizing:

- office files of product literature;

- cost data;

- reference material;

- samples.

SectionFormat

The three-part Section Format™ for construction specifications is also produced jointly by the Construction Specifications Institute (U.S.A.) and Construction Specifications Canada. Its primary purpose is to provide a uniform approach for organizing articles and paragraphs within the project specification sections to produce a consistent appearance and completeness, and to facilitate understanding and communication.

Sections, grouped together according to a collection of related work under one of the 48 identified divisions, can be combined and written to suit the project for which they are produced.

Each section is divided into three parts:

Part 1 – General:

This part covers those subjects which:

- relate to the work in general;

- provide a general description of the system, where applicable;

- identify references to standards;

- define the administrative and technical requirements specific to a particular section.

The indications provided in Part 1 are extensions and provide precision to the specifications sections featured under Division 01 and thus rely on these sections to be part of the specifications binder.

Part 2 – Products:

This part defines the acceptable equipment, materials, fixtures, mixes and fabrications, that is, “product” items to be incorporated into the work.

Part 3 – Execution:

This part describes the way items covered by Part 2 are to be incorporated into the work.

The architect should use the three-part SectionFormat as a guide in writing specifications sections for every project, except for:

- simple outline specifications;

- short specifications for minor projects.

The architect should maintain the established order and sequence of articles even if the three-part format is not used.

Master Specification Systems

Master specifications are template specification sections, published as stand-alone documents or as collections of specifications. They are usually grouped, numbered and titled by “Divisions” (numbered 02 to 48) under the MasterFormat standard nomenclature or “elements” (labeled A to G) under the Uniformat standard nomenclature. The sections are also usually formatted in accordance with the Construction Specifications Institute (U.S.A.) and Construction Specifications Canada standard three-part information structure respectively covering specifications relative to:

- General requirements as specifically relevant and applicable to the work described;

- Product/materials specifications describing the physical characteristics and properties of the prime and related accessory materials and products to be incorporated in the finished work as well as, where relevant, requirements applicable to fabrication procedures, usually all with references to relevant standards;

- Execution specifying requirements relative to means, methods and procedures to be used in the performance of the work and covering preparatory work, execution or installation methods and post-completion activities.

Master specifications collections also usually include specifications covering the general requirements applicable to the work covered under and complementary to construction contract agreement forms and general conditions. These are featured in what is commonly grouped under “Division 01” specifications under the MasterFormat standard nomenclature or “Element Z” under the Uniformat nomenclature. They are usually developed and organized for compatibility with specific standard contract documents and presented as such. Where and when used under other contract documents than those indicated, they may need to be edited so as to be adequately adapted to the overall contractual framework governing their application and interpretation.

Master specification section templates usually cover a wide range of applications commonly used in the building construction industry or available from the construction materials and products market for each of the specific types of work, materials, products or systems addressed in the various sections. The template provides blanks to fill in and/or options to select from. The more elaborate master specification sections also usually include annotations and commentaries to guide the editing process towards the final document, covering:

- the technical or contractual context for which the section is most appropriate to use, as a whole or for some of its contents;

- criteria to consider for editorial selection of various options or alternatives available from the template;

- correlation to be made between section contents and those of other contract documents (drawings, other specification sections, etc.).

Many sources are available to architects and specialized specifications writers for section templates.

The most wide-ranging, prominent, and commonly used general-scope master specifications in Canada is the Canadian National Master Construction Specification, more commonly known as the National Master Specification (NMS), currently developed and maintained by the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and required as the specifications basis for all federal government projects.

The National Master Specification (NMS) is the most comprehensive master specification in Canada serving as an easy-to-use framework for writing construction project specifications. The NMS is a reference document containing approximately 780 master specifications in both English and French. Each section is designed to be edited from the original master to produce a project-specific document. It is intended for use by the federal government, other public organizations, and the private sector in the preparation of construction and renovation contract documents.

NMS is based on the requirements of the National Building Code of Canada (NBC) and does not necessarily include all possible regional or municipal variations concerning products, methods, materials, systems, assemblies or accessories, their availability, or their method of construction. NMS is not structured to list or describe every product, material, system, assembly, or accessory required for an individual project and does not provide details for the entire execution of the required work. Execution statements should be restricted to text that describes what is required to achieve the quality of workmanship rather than describing how to construct, which could be misinterpreted as providing installation instructions (NMS User’s Guide, National Research Council Canada, 2017).

NMS is a nationally supported master specifications that is widespread in the construction industry.

Regardless of the source, the architect assumes responsibility for the specifications issued from the architectural practice.

NMS is a library of construction specification sections, written in contract specification format. Produced by the federal government in consultation with the private sector, it is the most widely used master specification in Canada. The NMS Secretariat, which is part of Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC), is responsible for the NMS. All data are stored electronically and organized into sections following MasterFormat.

NMS could be termed a “deletion” master. It allows for the fast deletion of inapplicable portions of the specifications, and the reduction of errors and editing time.

NMS is flexible and suitable for:

- large, medium or small projects;

- new or renovation construction;

- private or public (government) work;

- varying bid or contract arrangements.

It does not restrict the designer from:

- specifying any products;

- using any design concepts;

- employing any construction techniques.

Furthermore, NMS uses text that is clear, precise and detailed enough to convey the desired meaning. NMS also:

- incorporates the accumulated expertise of Canada’s foremost authorities on specifications, documents and construction technology;

- is reviewed by industry to ensure it represents current trade practices and construction technology;

- is regularly updated to incorporate the latest recommendations, use of products and construction changes, as well as standard and code revisions;

- is undergoing “green” revisions to ensure the incorporation of environmentally sustainable construction practices.

The Canadian Master Specification (CMS) is a master specification library, privately published and maintained by NBS Canada, and is similar in form, presentation and content to NMS.

Oriented to medium-sized and larger construction projects, the CMS includes the most common MasterFormat® Divisions from 00 through 48 and covers approximately 600 sections. This specification conforms to national format documents and is updated on an ongoing basis to ensure its currency. It is written to allow for performance, prescriptive, and proprietary specification methods.

A number of government clients (federal, provincial or municipal agencies, departments and Crown corporations) as well as other public sector institutions and organizations (hospitals, universities, colleges, etc.) and private corporations may also impose the use of their own standard master specifications sets. The range of building elements covered varies with the types of work the entity is most commonly and/or most likely to contract for under a limited number of types of projects.

These specifications templates usually allow for much less, if any, editorial licence from architects or engineers, as they represent the codification of that entity’s policy-based technical requirements and preferences from which designs are not usually permitted to deviate except in special circumstances. These section templates are also developed to suit the entity’s standard construction contract documents, including general conditions and general requirements. When tasked to work from such standard specifications, architects should familiarize themselves as early as possible with the embedded limitations to detailed design development they may create, to ensure that drawings are consistent within them.

Industry-sourced master or “model” specifications include:

- technical guides, recommended or best practice guides, narrow-scope model specifications that are developed, published and more or less regularly updated by various:

- major trade associations such as roofers, painters, architectural metals fabricators, etc.;

- major base construction materials supplier associations such as for concrete, masonry products, wood, metals, etc.;

- major construction products or pre-engineered building elements systems manufacturers, such as steel or concrete structural systems, windows and glazing systems, drywall systems, floor finishing systems, doors and hardware, exterior cladding systems and various other specialties;

- product-specific proprietary specification section templates that are also routinely made available by construction materials, products or systems manufacturers in support of their marketing efforts to facilitate their choice by architects for inclusion in their designs.

These model specifications can usually be relied on to align and be consistent with the other technical documents published by these organizations. Where architects rely on such documentation for design guidance, it follows that such model specifications can be relied on as source material to insert, in whole or in part, into the construction specification documents. Some circumspection is required from architects in using such source material, taking into consideration the credibility and reliability of the organizations involved – as such publications can be self-serving to the publishing organization.

Model Specifications

This is the name for a specification assembled to suit specific and similar kinds of projects, such as certain buildings within “Part 9” of the building code and some repetitive kinds of projects. Because the technology used to build such projects is common to the building type, such model specifications usually require minimal editing, except for describing site work which is unique to the location.

Office Master Specification Systems

Many architectural practices use a master specification, developed from experience on previous projects, which covers the entire potential scope of building construction, including a large range of options. Architects should be cautious to carry out periodic reviews of model specifications used over long periods of time to check for obsolescence of reference data and/or to insert updates and improvements revealed by experience in their use and/or the evolution of industry standards and recommended practices.

Working with the master, the architect or the specifications editor generally:

- fills in blanks;

- deletes options that do not apply;

- incorporates special requirements not included in the master specification.

Some offices have specifications prepared by their project architects. Others have a specification writer on staff, or engaged on a consulting basis, who takes the contents of the specification, in its raw state as provided by the architect, and edits it into the standard formats and expressions. These specification writers often enter the process during the production of the construction documents.

Proprietary Systems and Specification Writers

Many independent specification writing firms specialize in the preparation of technical specifications and bidding documents for construction projects, and the preparation of guide specifications for building product manufacturers.

Before selecting one of these firms to provide either a master specification or a specification developed and written for a single project, the architect should:

- review examples of the work of several firms;

- evaluate the appropriateness of their work for the architect’s needs;

- consult references.

Because ownership of the copyright can become an issue, the architect must:

- clarify the client’s expectations about ownership of the copyright;

- determine whether the specification consultant expects to retain the copyright of the specification that has been developed, and then negotiate an appropriate agreement.

Typically, the copyright of the documents at any stage of their development will be the property of the architect. If an architect chooses to engage an independent specification writer, the architect, as the prime consultant, will be responsible for the specifications but the copyright will generally rest with the specification writer unless it is assigned to the architect. The architect retains the right to modify the text as provided. In addition to the final hard (paper) copy, an electronic copy should be submitted.

The specification writer or “specifier” should always be well-informed on the progress of the project and current with the production of all documents, including drawings and schedules. This ensures consistency and proper coordination between the specifications and the drawings.

Some specification writers are members of Construction Specifications Canada (CSC). See Chapter 2.3 – Consultants for a brief description of CSC.

Preparing Specifications

Resources

The maintenance of a comprehensive and effective office library is crucial to preparing specifications. The office library (hard copy, electronic copy or hybrid) should contain:

- manufacturers’ and suppliers’ product literature;

- trade association handbooks and design guidelines;

- guides related to contractual and procedural information (such as CCDC Guides);

- research material which provides data on the performance of construction components, assemblies, and systems under various conditions;

- standards (which prescribe the manufacture, performance, and installation of various products);

- national and provincial codes and regulations;

- local bylaws and regulations (such as zoning bylaws).

In cases where a new or unusual product is to be selected, the architect will usually research the product and its specifications. Note that:

- the specifications can only be drafted after the quality and performance of the new product has been evaluated;

- it may be necessary to obtain samples or to conduct site visits where the product has been installed.

Although most manufacturers’ representatives are knowledgeable about their products, the architect generally:

- seeks further information;

- reviews the firm’s literature;

- asks for test reports from independent laboratories;

- contacts other architects or users who have had experience with the material or product.

Coordination

The architect continually acquires information affecting specifications and maintains close coordination among all contributing parties during the process of writing the specifications.

These parties include:

- the client representative;

- members of the architect’s staff associated with the project;

- structural, mechanical and electrical engineers;

- specialist consultants;

- technical representatives from materials and equipment manufacturers;

- authorities having jurisdiction;

- testing agencies;

- trade associations;

- the cost consultant.

It is important to establish well-defined lines of communication for sharing information among the client, authorities having jurisdiction, the architect’s staff and consultants.

Assembling Specifications Sections

The specifications can be assembled as the project design is developed and the components of the project are identified.

Architects may follow these steps:

- obtain a copy of the master specifications for the section if one is available (alternatively, if the section is new, have a copy of the three-part SectionFormat for Construction Specifications to assist in writing);

- review the minutes from project meetings and identify specification items;

- study the latest drawings and schedules and the use of the materials noted;

- attach a checklist to each section listing:

- action required;

- questions to be answered;

- information to be obtained;

- draft the section, marking items to be resolved on the draft;

- coordinate all references to standards and codes to ensure that they are current and appropriate for the product or system application;

- coordinate with other sections and with drawings, when preparing each draft section;

- finalize the draft;

- edit and proofread the text;

- correct and reprint until a final copy is achieved.

Revisions

As the construction documents develop, the architect incorporates a number of revisions into the specifications. The final specifications include:

- design revisions affecting the materials to be used;

- revisions which change the methods by which a material is used;

- changes requested by local authorities having jurisdiction, such as:

- additional fire-rated protection;

- the prohibited use of a material in each situation.

Office Procedures and Standards

Each architectural practice will develop its own standards for formatting, text editing, word-processing, and producing the specification documents. Only the significant points are stated here. Refer to the CSC Manual of Practice for a detailed description of procedures.

SectionFormat™

The “section” of a specification is intended to cover a subject, component or unit of work of the project. The information and instructions contained in the section must be organized in a consistent manner, as recommended in SectionFormat.

PageFormat™

The practice should develop a standard page format for specifications. Some editing software programs provide options which automatically change the page format.

The office standard should:

- maximize use of the text area on the page;

- avoid excessive indenting of paragraphs;

- recognize that some clients may require a style and font that differs from the architect’s standard.

The text for the printed page must be easy to read and to quickly and thoroughly understand.

Formatting should:

- use the same layout and typeface (font) throughout the document;

- issue clear instructions on format to:

- in-house staff;

- consulting engineers;

- specification writers.

The choice of font is also important for ease of communication. The base font should be easy to read. Provide variations, such as a small increase in size (for headings, for example), bold face or italics to emphasize certain components of the text or to highlight certain kinds of information.

Covers should present the practice’s image in a professional manner.

Project identification:

- includes project number;

- includes date:

- usually selected by the architect as the completion date of all documents;

- the date must be the same on all bid documents and all contract documents;

- is identical on all documents including:

- drawing title blocks;

- specifications cover;

- specifications title page (particularly if cover is blank or contains graphics);

- covers for separate volumes (schedules, standard details, etc.).

Reproduction and binding should consider the fact that specifications are used extensively at the construction site, often in rough conditions and sometimes wet weather.

For information on the number of sets to be printed, see Chapter 6.5 – Construction Procurement.

Specification Language

When writing specifications, follow these well-known maxims:

- be brief and clear;

- use active imperative style;

- address instructions to the contractor;

- avoid:

- repetition;

- specifying anything that is not to be enforced;

- or equal phrases;

- scope or scope of work paragraphs;

- weasel paragraphs (see below).

Use technical terms in such a way as to be understood by a non-specialist. Specifications communicate a message to the people responsible for building the project.

- Use a simple imperative style. Avoid verb forms such as: shall be, will be, to be, is to be, are to be, should, should be, and may be. Avoid the word must.

- Make direct, positive statements. Make materials and methods the main subject, not the contractor. Write specifications as if the work will be done by one constructor. Avoid reference to: mechanical contractor, plumbing contractor, subcontractor, general contractor, main contractor, etc.

- Avoid vague or escape phrases, for example: as specified, as shown on drawings, specified elsewhere, to the satisfaction of architect, as architect may direct, acceptable to architect, in opinion of architect.

- Avoid “weasel” paragraphs (such as the following actual examples):

“The contractor shall furnish and include everything necessary for the full and complete construction of the building whether shown or specified or not shown or specified.”

“Any work which would necessarily be required to properly carry out the plans must be considered as included in these specifications, although the same may not be specifically mentioned.”

- Avoid superfluous words such as: all, any, which, same, and/or. Avoid using the definite article “the” or the indefinite articles “a” and “an.”

- Avoid the phrases: workmanlike, high-class job, first-class job, etc. Describe the result in known precise terms. Do not specify anything not intended to be enforced or impossible to enforce. Avoid adverbs such as “carefully” or “neatly.”

- Use numbers for numeric quantities.

- When a numeral or letter is used as a descriptor as in a list, add a period to distinguish it from a quantity.

- Use abbreviations or acronyms if they are well-known in the industry. (Consider including a glossary that spells out abbreviations or acronyms in full.)

- Avoid the following phrases: or equal, approved as equal, equal to, or just as good.

- Avoid repetition – say it once, in the appropriate place.

- Avoid writing scope, scope of work, or work-included paragraphs. There is a time-honoured rule of law which reads: “Expressio unius est exclusio alterius.” This means literally: The express mention of one thing implies the exclusion of another.

- Ensure consistency in style and in the use of terms.

Complete sentences are not necessary in specifications. The information can be conveyed by simply naming the product and relating it to a standard or list of criteria.

For example:

.2 Acoustic units: to CAN/

CGSB-92.1, 24” x 24”, mineral fibre, 3/4” thick

NRC range .65 -.75, colour white — face cut pattern

or:

.2 Acoustic units: ‘Acoustone’ Glacier, by CGC — colour white

The Bid Package

See “Appendix A – Checklist: The Bid Package: A List of Information Required” in Chapter 6.5 – Construction Procurement.

Addenda

Addenda are revisions to the specifications and drawings prepared during the bidding period. See Chapter 6.5 – Construction Procurement.