Editor’s note: Most construction agreements define contract documents to include both drawings and specifications, with the anticipation that they are complementary. For this reason, and because of the evolution of practice, previous separate chapters about drawings and specifications have been integrated into a single chapter together with appendices focused on both drawings and specifications.

Definitions

Attribute: Data (such as a door number or column) attached to an entity, block or symbol within a CAD drawing.

BIM or Building Information Model: A building information model (BIM) is a digital representation of physical and functional characteristics of a facility. As such, it serves as a shared knowledge resource for information about a facility, forming a reliable basis for decisions during its life cycle, from inception onward. A basic premise of BIM is the collaboration between stakeholders at different phases of the life cycle.

Construction Documents: The working drawings and the specifications. When combined with the contract and contract conditions, these documents form the contract documents.

Coordinate: To bring (parts, movements, etc.) into proper relation; cause to function together in proper order.

Coordination: The arrangement and direction of work of others by a person (e.g., supervisor) or entity (e.g., general contractor) in a special manner to minimize conflicts, delays, interferences, etc., among such others.

Deliverables: In the context of this chapter, refers to the output of the final design work in the form of “instruments of service” required to provide all construction stage stakeholders and participants with the information necessary for the performance of their respective obligations and roles during construction.

Drawing: Graphic information, which may also contain text, organized on a two-dimensional surface for the purpose of conveying information about a specific portion of a project.

Layer: A group of functionally similar bits of information that can be manipulated or displayed as a unit and that possess common attributes; a property of a CAD drawing used for classifying information in order to control visibility and manipulation; sometimes called a “level.”

Process: The scope and requirements applicable to design work to be performed as the immediate precursor to the procurement and execution of actual construction work.

Schedule: Tabulated information on a range of similar items, such as a “Door Schedule” or “Room Finish Schedule.”

Introduction

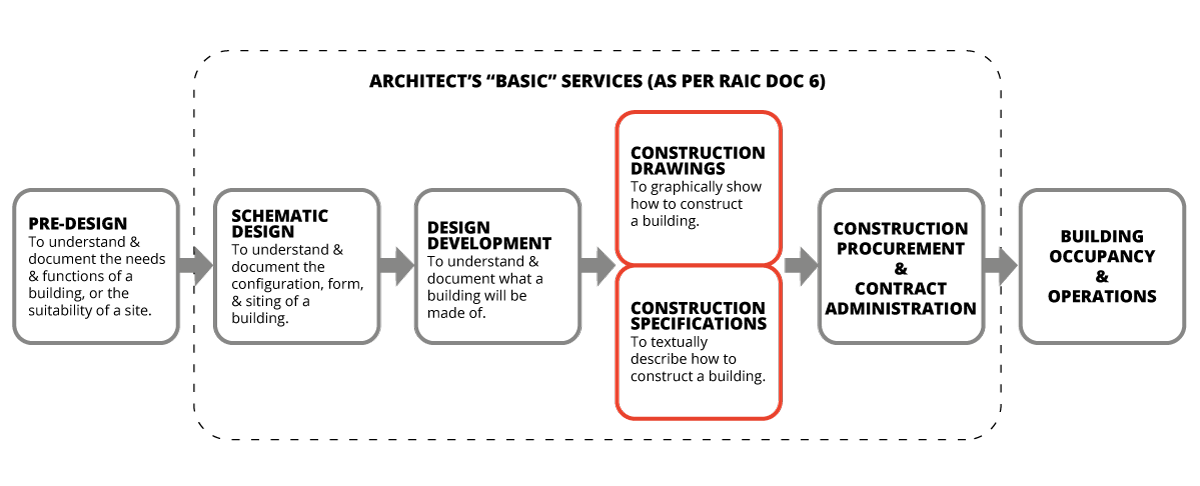

The construction documents stage of the design services is generally where:

- the client’s project objectives as defined at the pre-design stage are captured for construction, especially with respect to costs, time and overarching considerations such as sustainability, durability, life cycle, etc.;

- the architect’s design intents formulated at the schematic design and design development stages are also described in detail in both drawings and text for construction.

Construction documents are also the architect’s primary reference and resource in performing construction contract administration services. Construction contracts usually name the architect (or engineer) authoring the construction drawings and specifications as having primary authority over these documents for the purpose of evaluating construction work, quality and conformity. It is important, therefore, that construction documents provide a transparent, straightforward and unambiguous basis for construction contract administration services in order to minimize the opportunities for disagreements, disputes or claims to arise from contractors.

It is at this stage that the project information developed and consolidated at the previous stages and accepted by the client comes together in the building’s definitive design solutions for all its elements and components, across all disciplines and at a level of comprehensiveness, depth and precision appropriate to the project’s chosen methods of procurement, construction work and delivery.

It also follows that the architect’s management of the services performed and deliverables produced at this stage call for the greatest attention and diligence with respect to professional liability risks implied through the use of the design information by project stakeholders, including the contraction forces, during the construction and post-construction stages of the project.

The quality of information developed at this stage also directly impacts the architect’s services during the construction contractor procurement and construction phases. Finally, this information will generally be the basis for obtaining necessary permits for construction from the authorities having jurisdiction (AHJ). Therefore, the information in construction documents needs to clearly describe conformance with regulatory requirements.

This chapter discusses the scope of work and quality management to be addressed by architects in delivering services during the construction documents phase. The level of attention and effort to be invested in the management of service delivery will vary in accordance with the particulars of the building project (intended use, performance goals, technical and project management context, etc.) as well as with the terms of reference of the architect’s professional services contract.

Architects are involved in a variety of projects, including projects for small buildings, generally in the commercial or residential sector; very narrow-scope work involving small parts of buildings; work involving a single trade or type of work; and repetitive or near-repetitive projects. Regardless of project scale or type, the recommendations of this chapter, as well as the requirements to provide services in a manner consistent with the standard of care for service delivery by self-regulated professionals, must be considered.

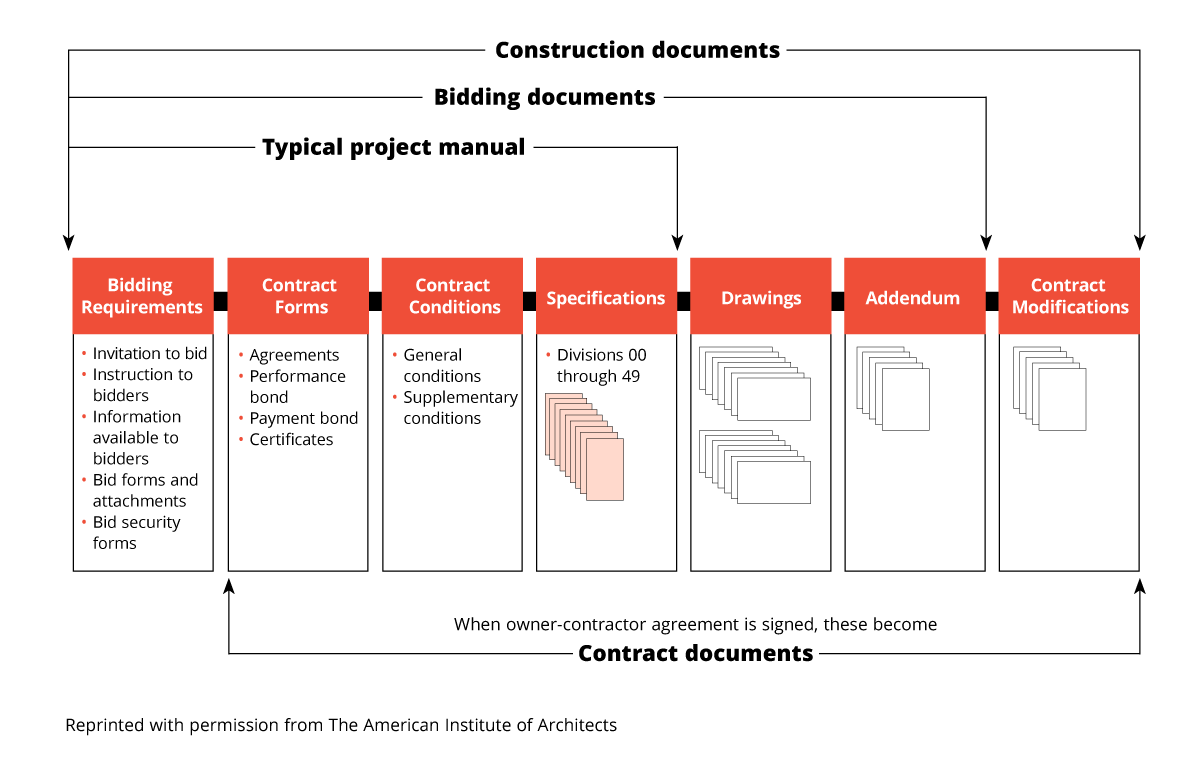

Context

Construction documents include drawings, specifications and related documentation authored by the design professionals. In Canada, both are required for almost any project requiring the services of an architect. They are an integral part of what is commonly defined as the construction contract documents and may also be part of a project manual for use as construction tender documents. The operating definition of construction documents is generally stated in either or both of the tender documents and the construction contract. Construction contract forms and associated documents are discussed in Chapter 4.1 – Types of Design-Construction Program Delivery. Bid documentation is discussed in Chapter 6.5 – Construction Procurement. Common industry practice is to have construction contracts include language such as:

“Drawings and specifications are complementary and what is called for by one shall be as binding as if called for by both.” It is also standard industry practice to include contractual provisions governing the order of precedence of the documents for the purpose of their interpretation should perceived inconsistencies occur. Typical wording is as follows:

1.1.7 If there is a conflict within the Contract Documents:

.1 the order of priority of documents, from highest to lowest, shall be:

.1 the Agreement between the Owner and the Contractor,

.2 the Definitions,

.3 the Supplementary Conditions,

.4 the General Conditions,

.5 Division 1 of the Specifications,

.6 Technical Specifications,

.7 Material and Finishing schedules,

.8 the Drawings.

.2 drawings of larger scale shall govern over those of smaller scale of the same date.

.3 dimensions shown on Drawings shall govern over dimensions scaled from

Drawings.

.4 later dated documents shall govern over earlier documents of the same type.

(CCDC-2 (2008) Stipulated price contract – General Conditions)

Architects should review proposed construction agreements to determine if there are any variations to either the definition of contract documents or the order of precedence.

Because of the typical complementarity between drawings and specifications, their development should be closely integrated. Management of design information involves careful coordination between drawings and specifications to minimize gaps and overlaps or other inconsistencies either internally within distinct disciplines or between each other. An over-simplified but general rule of thumb is drawings reflect the scope of a design while specifications describe its quality.

The development of construction documents should directly flow from the design documentation that was produced at the previous stages and approved by the client (see Chapter 6.2 – Schematic Design and Chapter 6.3 – Design Development).

Construction documents phase services are generally undertaken on the assumption that critical design issues in all disciplines have already been resolved and coordinated so that:

- there is a high degree of confidence about the feasibility of solutions adopted;

- no pivotal design decisions have been deferred to the construction documents stage.

Critical design issues involve:

- building elements whose design is, owing to project context or governing parameters, most constraining to other elements or systems;

- issues whose late resolution may have considerable impact on the design of other elements or systems;

- designs or issues already committed to, that cause unnecessary/effort-consuming rework and schedule delays.

As a rule of thumb, all user stakeholder requirements, and regulatory issues, including building code compliance, should have been addressed and resolved before entering the construction documentation phase.

Traditionally, architects assume the roles and responsibilities of design coordination and preparation of construction documents. This role as “coordinating professional,” often called prime consultant, is not always clearly defined in services contracts (of either the architect or professionals in other disciplines) and it is important for the architect that the related tasks and duties assumed are transparently expressed and communicated among all project stakeholders. The Canadian Standard Form of Contract for Architectural Services Document Six – 2018 Edition provides the following definition:

GC1 Architect’s Responsibilities and Scope of Services

1.1 The Architect shall:

………

.9 perform the Services of the coordinating professional who:

.1 manages the communications among all Consultants identified in Article A11 of the agreement and with the Client,

.2 provides direction to all Consultants identified in Article A11 of the agreement as necessary to give effect to all design decisions, and

.3 reviews the services of all Consultants identified in Article A11 of the agreement to identify matters of concern and monitor Consultants’ compliance with directions . . .

The Process

The construction documents phase is when the building and site design has been:

- formulated through the schematic design stage;

- elaborated at the design development stage;

- validated for feasibility;

- accepted and approved by the client;

- further studied and developed to the level of detail, accuracy and interdisciplinary integration required to validate technical design choices for building materials, systems, and technologies against governing project requirements.

Until complete and ready to be issued as bid or contract documents, construction documents in development are often referred to as “progress” documents (drawings or specifications). These interim versions of design information are used to communicate and distribute information within the design team and to others, as appropriate at various stages of development or as needed.

The Deliverables

Construction document deliverables are essentially, but not exclusively, comprised of:

- drawings which illustrate the spatial arrangement of building elements and their interconnections in graphic form;

- specifications which describe the material, quality and workmanship, requirements and the criteria and methods to be used to validate acceptance of the work upon completion in written form;

- schedules in tabular form to communicate detailed information about systems and elements, such as:

- building code compliance;

- door and frame design, dimensions and materiality;

- floor, wall and ceiling finishes;

- electrical panel configuration; or

- air handling unit capacity and configuration details;

- complementary documents developed as appropriate to the project’s context, to highlight interdisciplinary or multiple-trade based design information relative to various building elements, and integrate information from drawings and specifications, all at the level of detail necessary to direct builders in the execution of construction work, so that the completed building conforms to design intents and technical performance requirements as per the owners’ expectations documented in contract documents.

General Requirements for Construction Documents

Overarching criteria for the effectiveness of construction documents include:

- Clarity: Documents need to convey design information in a manner that minimizes the risk that information could be misinterpreted or misunderstood, or could contribute to misleading use of the documents. Building design information should be transparently intelligible and coherent across all disciplines. Key factors to achieving clarity in the document set are:

- information provided is directly relevant to the work to be performed;

- cross-referencing methods to avoid redundancy, overlaps and content/media mismatches;

- legibility of drawings with respect to consistent graphic standards (scales, line styles, symbols, etc.);

- quality of written contents (specifications and drawing annotations):

- consistency and suitability of the terminology used;

- language and wording styles consistent with design and construction common usage.

- Readability: Document layouts and presentations, especially drawings, are uncluttered. Information is presented in a logical sequence allowing all project stakeholders to understand the intent of the designer without hunting and searching.

- Intelligibility of design solutions: The documents, drawings, should be as transparent as possible in representing the design intents, especially with regards to architectural features. Construction assembly detail drawings or specifications should be reasonably self-explanatory to qualified and experienced users. This includes how work performed under one design discipline or trade interfaces and is coordinated with that of other disciplines or trades, fostering a correct, common understanding of the project’s design intents and logic as a comprehensive whole rather than as discrete disjointed parts.

- Constructability/feasibility: Includes the actual, material, and technical feasibility of the design solutions with respect to the foreseeable sequencing of the construction work by various trades. The design is constructible in the location of the work with available materials, products, equipment, and skilled trade labour. Innovation or unique construction methods, procedures, technologies or techniques are verified to be feasible in the context of the procurement method selected and/or explanation in/of the contract requirements.

- Usability: Adequacy and sufficiency of the construction documents relevant to:

- bidders for tendering, in particular with respect to bidders’ cost estimates for labour and materials, as well as professionals for tender analysis;

- general and trade contractors as well as product suppliers and systems manufacturers for the management and execution of construction work and professionals for construction contract administration;

- project stakeholders for construction stage completion and building commissioning, take-over, use and occupancy by the owner.

- Quality of graphic and written language: Documents free from structural, orthographic, grammatical, syntactic or semantic errors, including: adequacy and accuracy of cross-references between and within drawings sheets and sets, technical specifications sections, or other contract documents.

- Written material:

- correct syntax, grammar and spelling in written language;

- use of appropriate terminology and phrasing, consistent across all documents.

- Graphic material:

- correct use of commonly accepted standards for graphic representation (line types, line weights, symbols, hatch patterns, etc.) of various types of information, consistent at all scales and across all drawings;

- accuracy and graphic consistency of drawing’s set navigation indications (cross-referencing symbols, tiles placement, fonts, etc.) across all drawings.

Editorial defects such as those noted above may also impact the interpretation of documents by various users and contribute to misunderstandings, disagreements or disputes.

Planning the Production of Construction Documents

Architects should refrain from undertaking the preparation of construction documents prior to obtaining client approval of the deliverables of design development. A formal written approval should be issued by clients.

The construction documents phase is generally the project stage that involves the architect’s greatest expenditure of time and resources, although front-end loading of the work when using the BIM process may alter the distribution of work and fees. Refer to the fee distribution tables in the RAIC’s A Guide to Determining Appropriate Fees for the Services of an Architect for a comparison of fee distribution in traditional design processes versus in BIM processes.

It is important that the architect inform the client of any substantial changes introduced to previously approved design work and receive confirmation of the client’s acceptance of those changes. The architect should keep the client abreast of progress on the construction documents and remind the client that significant changes to the design from the design development phase may significantly impact the costs and schedule.

In the capacity of “coordinating professional,” the project architect or project manager is usually the individual responsible for planning the production of construction documents. When scheduling this work, the project architect must consider the following factors:

- available production budget;

- available human resources;

- firm’s material resources and computer systems (hardware and software);

- time frame for production of the construction documents;

- human and material resources available to the other consultants.

These factors must be balanced against the content requirements predicated by the project’s approved schematic design and intended method of construction procurement.

The project architect must therefore:

- develop the work breakdown structure, including all the work of construction document production;

- determine what drawings and information must be produced;

- organize production of construction documents across platforms, i.e., production methods, file formats, deliverables formats, etc.;

- estimate the duration of key activities necessary to produce each document;

- assign production, supervision and coordination tasks;

- prepare a production activities schedule of milestone dates;

- manage and coordinate the work with all team members on a continuous basis.

Prior to the start of the construction documents phase, the project architect should have a meeting with the entire consultant team. A suggested agenda is included in Appendix C – Proposed Pre-construction Document Phase Design Team Meeting Agenda. It is important for the architect to manage this stage of the work so that work plans are consistent with the contracts for services, between both client-architect and architect-consultant. If necessary, with the client, agree to the necessary revisions to schedules and/or fee structure as warranted.

The project architect in charge of managing the production of the complete set of construction documents coordinates the work of the design team (engineers and other consultants). Usually management and coordination of engineers and other consultants is a part of the architect’s services and responsibilities; however, occasionally this is contracted to others. One of these responsibilities is to ensure that all the necessary reference documentation is available and distributed to all members of the design team prior to the start of the work and is updated regularly.

The “Checklist for the Management of the Architectural Project” in Chapter 5.1 – Management of the Design Project can assist in planning the production of construction drawings. The internal review checklist(s) appended to this chapter can serve as templates for the construction documents stage of planning of contents.

Construction documents are not merely for the purposes of communicating technical information to the construction contractor and municipal plans examiner. They must capture the aesthetic of design. The list below highlights considerations in the planning of the construction documents to effectively communicate the intent of the design:

- the project’s overall design values in terms of technical, geometric, volumetric and programmatic complexity;

- consistency of the documents, with the project delivery methods selected by the client;

- compatibility with the construction contract requirements, including contract general conditions, tendering procedures, and general requirements stated in Division 01 specifications;

- the level of sophistication, customization and innovation developed in upstream design stages is articulated in the construction documents in a way that validates the design solutions and decisions adopted during the previous stages;

- the documents should demonstrate that the project can be completed at the level of quality required by the client and user stakeholders, contingent upon the following:

- design decisions and information have been sufficiently developed at the schematic design stage;

- the resolution of key design issues has not been deferred to the construction documents stage;

- design decisions at the concept and schematic design stage have been made acknowledging the workload involved to translate design intent in constructible, readable, integrated details using appropriate materials;

- the significance or importance of overarching considerations such as heritage value, conservation, environmental sustainability, life cycle durability, and/or commissioning requirements are captured.

In cases involving projects where construction is undertaken while the facility remains in use, drawings may be required to illustrate requirements for temporary work. In the case of restoration or preservation work in heritage structures, the scope and nature of the work may require highly detailed survey drawings bearing comprehensive explanatory annotations. Annotated photographs can also be effective graphic representations of the work to be performed.

The project delivery method adopted at either of the previous stages of the project, and more particularly, the terms of construction contracts, directly influence the definition of the scope and substance of construction documents and also set the stage for the planning of the construction document work.

Various project delivery methods are selected for their respective strategic value towards the achievement of the client’s objectives, project context or priorities. (See Chapter 4.1 – Types of Design-Construction Program Delivery for discussion on the features and characteristics of the various methods.) The effectiveness of each of these methods is predicated on specific critical conditions of success being met, including the terms of reference of construction contract and procurement methods which predicate the quality requirements applicable to construction documents.

Stipulated price or lump-sum construction contracts (CCDC 2, CCDC-17) and Cost-Plus with Guaranteed Maximum Price (CCDC-3) contracts in particular implicitly require that information provided in the construction documents can be relied on as fully coordinated across all disciplines and trades, and complete with respect to the description of the work to be performed in terms of scope (quantities), technical performance results, detailed descriptions of assemblies and selection of materials, systems and products. This is made necessary by the principle governing such contracts — if reasonably able, contractors are expected to commit to contract prices, on the basis that information provided by construction documents is sufficiently complete and accurate. Complete and accurate documents allow the contractor to accept, with near certainty, the costs in materials, products, labour, equipment and management effort required for the performance of the work, while conforming to the client’s expectations for the approved designs. In these types of contracts, any additional information provided to contractors during execution of the construction work is justifiably expected to have only minor, if any, impact on initial contract price or contract time, or on quality of the work executed either on the element affected or others related.

All forms of contracts (lump sum, cost-plus, unit price) are also predicated on the basis of a contract price and contract time being agreed to by the contractor for a demonstrably clear scope of work and performance requirements, and on the basis that they are entered into as a result of a well-informed, responsible decision, whether in the course of a fair competitive tender process, publicly or privately conducted, or as a result of direct negotiations.

When the project is undertaken using the construction management project delivery method, the construction work is generally divided into separate work packages, each with a distinct procurement process and contract. Each of these contracts will require its own specific set of construction contract documents, specifying the scope of work covered and providing information regarding the interface of such work with that executed on other contracts.

Especially in the case of large or technically complex projects, construction management contracts usually provide for the construction manager’s involvement in the project at the pre-construction stages:

- to provide advice and counsel to the design professionals team regarding design decisions related to the project’s goals, constraints or priorities with respect to:

- compatibility with construction budgets and client-approved cost plans and projections;

- feasibility/constructability issues arising from design solutions and technical or technological choices and/or from site conditions;

- project management feasibility issues arising from prevailing or foreseeable construction industry economic market conditions;

- to prepare advance construction stage work plans, including work sequence and time schedules to inform design decisions that can be affected by constructability or the feasibility of achieving technical performance requirements;

- to develop, with the collaboration of design professionals, general contract requirements applicable to all work packages (“Division 01” specification sections) where such requirements may affect the form and contents of construction documents (drawings or specifications) with respect to their use for construction work and with respect to the incidence of various requirements regarding contractor submittals and the impact of overarching quality requirements;

- to collaborate with design professionals in the initial detailed definition of the information to be developed for construction contract documents (drawings, specifications and other supporting documentation) for the various foreseen construction work packages in accordance with their respective scope, intended method of procurement and specific information requirements in terms of form and substance.

The construction management team’s contribution in the management of the construction documents can also be considered a necessary area of involvement from the perspective of its direct contractually defined roles and responsibilities, with respect to the overall management of all of the project construction information.

The subdivision of the entire building construction stage in specific work packages can take many forms and many combinations of forms depending on the nature and context of the project. Several construction management strategies are conceivable to achieve the intended results, and no one is best in all circumstances. The work can be subdivided by:

- construction trades or specialties;

- physically separate building parts or sectors involving multiple trades;

- separating work between “base-building” and interior fit-up construction;

- any combination of these breakdown approaches.

Design and construction are interrelated. The planning and scheduling of the design work has a direct impact on the development of designs to the level required for construction contracts. The most common contexts generated by construction management are:

- Sequential tendering of work packages to follow either the phasing of the work or the physical sequencing of the work as logically governed by physical characteristics of the building’s design. In this case, a near-complete set of construction documents is used to extract contract document packages to be issued for procurement as work progresses. All key or critical elements of the design are by then fully resolved and coordinated. Only elements of minor impact or whose final design is inconsequential to previously contracted work may be left to be completed.

- Fast-tracking of design and construction is also often used where projects are sought to be completed in the shortest possible time frame. In this case, the development of design is taking place concurrently with early construction tasks. It is important for architects and the design team to understand that the logical sequence of work featured in the construction schedule does not mirror the logic of the development of the design. As an example, structural design is often described as progressing from the top down due to the cumulative loads that act upon a building’s structure, while the actual construction of the structure is from the bottom up. Therefore, where building footings may be the last structural element to be designed, they are the first to be constructed.

The scheduling of construction work does not affect the necessity for design professionals to develop design solutions for all of the critical elements of the projects prior to completing the construction contract documents for early stage work. This ensures that completed work is fully compatible with work to be performed later. Under a construction/design fast-track strategy, design decisions affecting construction work executed early in the construction sequence, but not fully determined by the final design for work to be executed later, are all but irreversible and compromise the achievement of design priorities as set out in the design development documents approved by the client. The impact on the results for architectural features – in particular, interior and exterior – can compromise and in some cases defeat the achievement of key design intents.

In some cases, as in extensive building renovation, adaptive reuse or heritage rehabilitation projects, or when existing site conditions present significant risks or uncertainties impacting design decisions, construction management can facilitate the execution and completion of preparatory prior to completion of design work, even as early as at the schematic design stage. These work packages are not design-information intensive, and construction documents can readily be prepared for the execution of the following examples:

- partial or total demolition of existing structures;

- site excavation, decontamination, and other site preparation or civil works, including archeological surveys in heritage properties;

- selective demolition of various building elements or systems and interior stripping work, including, where necessary, invasive or destructive investigations of existing conditions of various elements.

Such tasks are conducted for the purpose of providing the design team with complete and reliable data on pre-existing conditions to fully inform the detailed development final design solutions and to prepare more complete and accurate construction contract documentation.

In all cases, the final set of construction documents, as part of the project manual (specifications, contract forms and contract conditions, and bidding information), should provide all of the necessary and sufficient information required to:

- prepare confident bids or accurate construction cost estimates (quantity and type of materials and their application);

- obtain the building permit and other approvals from authorities having jurisdiction;

- plan and direct the sequence of construction work across all trades in a manner appropriate to the achievement of workmanship and performance requirements for the project.

Construction Documents’ Quality Assurance and Quality Control

Construction document quality concerns have a direct impact on the client’s satisfaction with the architect’s services. The quality of construction documents has a direct impact on the time and effort required of the architects in the performance of services at the next stages of a project.

Basically, defects or flaws in construction documents can be remedied during the tender stage or even the construction administration stage of services, but generally at a significantly greater cost of time and effort and greater liabilities and risks than would be involved with adequate quality assurance and control at the construction documents stage. For this reason, the initial planning and organization of the construction documents work is important to achieving the quality level of documents commensurate with the project’s context, scope and design.

Key issues to be addressed as part of quality reviews include:

- continuity and compatibility with approved design development documents and requirements implied in the construction procurement process;

- consistency of document format, form and presentation standards established at start-up;

- errors, omissions or ambiguities in document contents and form;

- sufficiency, completeness, relevance and internal consistency of construction information within drawing sets and specifications;

- compatibility and consistency of detailed design solutions between disciplines and between related trades on specific building elements or systems.

Except where design involves highly standardized, commonplace conventional solutions, careful attention should be given to the development of information details in both drawings and specifications that resolve actual, physical field feasibility and constructability concerns. Even when commonplace proprietary products and systems are used or when industry-typical, generic configurations are being implemented, careful attention must be given to:

- the feasibility of achieving building envelope integrity in terms of reliable and durable continuity of thermal insulation, air barriers, vapour retarders and waterproofing layers and assemblies at building plane two-dimensional or three-dimensional intersections, as well as at junctions between distinct construction systems (walls, roofs, windows, doors, etc.) involving separate trades;

- the material feasibility of achieving full conformity with building codes and regulations requirements, especially with respect to the integrity of fire resistance requirements of fire separations;

- the feasibility of achieving the expected level of quality and architectural effect of interior finishes (materials or product/systems).

See also the internal review checklist(s) appended to this chapter.

See also Chapter 5.4 – Quality Management.

References

Afsari, Kereshmeh, and Charles M. Eastman. A Comparison of Construction Classification Systems Used for Classifying Building Product Models. 52nd ASC Annual International Conference Proceedings, April 2016.

Demkin, Joseph A. (ed.), American Institute of Architects. The Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2013.

Guthrie, Pat. Cross-Check: Integrating Building Systems and Working Drawings. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1998.

Nigro, William T. RediCheck Interdisciplinary Coordination, 6th Edition – 2015. The RediCheck Firm. http://www.redicheck-review.com/TheSystem/RedicheckBook.aspx.

“United States National CAD Standard – V6.” National Institute of Building Science, 2017. https://www.nationalcadstandard.org/ncs6.

Canadian Construction Documents Committee (CCDC). CCDC 23-2018: A Guide to Calling Bids and Awarding Construction Contracts. Ottawa, ON: CCDC.

Klien, Rena M. (ed.), The American Institute of Architects. The Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice, 15th Edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

Environmental Protection Agency. “Federal Green Construction Guide for Specifiers.” Whole Building Design Guide. https://www.wbdg.org/ffc/epa/federal-green-construction-guide-specifiers, accessed July 7, 2020.

National Research Council Canada. Canadian National Master Construction Specification (NMS). https://nrc.canada.ca/en/certifications-evaluations-standards/canadian-national-master-construction-specification, accessed July 7, 2020.

National Research Council Canada. NMS User’s Guide. 2017. https://nrc.canada.ca/en/certifications-evaluations-standards/canadian-national-master-construction-specification/nms-users-guide, accessed July 7, 2020.

Stitt, Fred A. Construction Specifications Portable Handbook. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1999.

Appendix

- Appendix A – Copyright and Architects

- Appendix B – Digital Seals

- Appendix C – Proposed Pre-construction Document Phase Design Team Meeting Agenda

- Appendix D – Drawings

- Appendix E – Specifications

- Appendix F – Checklist – Internal Review of Drawings: Architectural

- Appendix G – Checklist – Internal Review of Drawings: Structural

- Appendix H – Checklist – Internal Review of Drawings: Mechanical

- Appendix I – Checklist – Internal Review of Drawings: Electrical

- Appendix J – Checklist – Life Safety Information to Include on Drawings: Architectural

- Appendix K – Checklist – Life Safety Information to Include on Drawings: Structural

- Appendix L – Checklist – Life Safety Information to Include on Drawings: Mechanical

- Appendix M – Checklist – Life Safety Information to Include on Drawings: Electrical

- Appendix N – Checklist – Information to Include on Drawings for Small Part 9 Buildings

- Appendix O – National Building Code Data Matrix