Wanda Noel, Barrister and Solicitor

Revised October 2019: Ariel Thomas, Barrister and Solicitor

The Issue

People who produce material in digital form often think that “www” stands for the Wild Wild Web. They ask themselves whether freedom on the Internet means the freedom to use the creative works of others, without asking permission or paying the copyright holder. With a few computer commands, anyone can copy electronic information and transmit it quickly and easily. The challenge facing architects is how to ensure payment for the use of their work when digital technology has made copying and distribution so fast and easy.

The Right to Control Copying

Copyright in Canada is set out in the federal Copyright Act. Because the Copyright Act is a federal statute, it applies throughout Canada. Under copyright law, unless there is permission or a licence from the owner, generally speaking, it is unlawful to copy, reproduce, publish, modify or transmit copyright-protected material. This is the law in the print world. It is also the law in the digital world. Although that is the law, the application of copyright in a digital environment is not always easy.

Why Is Copyright Important to Architectural Practice in a Digital Environment?

Architects should be concerned about people using their work without permission or paying the appropriate fee. They should also take care not to unfairly use the work of others. The legal term for unauthorized use is “copyright infringement.” Digital technology has made copyright infringement much easier. People have long been able to photocopy plans and texts, and record music and television shows. Such “leakage,” as copyright lawyers call it, has always existed. However, with digital technology, this leakage threatens to turn into a flood. For example, plans in digital form can be copied and distributed by e-mail in minutes, a dozen or even a hundred times. Digital technology makes unauthorized copying of material protected by copyright fast and very easy. Therefore, knowing how copyright law protects architects is especially important in a digital environment.

Architectural Works Are Protected by Copyright

The Copyright Act protects architectural works in a category of material called “artistic works.” Artistic works are defined to include drawings, charts, plans, photographs, works of artistic craftsmanship (such as models) and architectural works. An “architectural work” is defined as “any building or structure or any model of a building or structure.” As a result, the building is protected by copyright, as well as the various drawings, sketches, designs and models produced as part of the project.

Architects Own the Copyright in their Works

Under the Copyright Act an architect is an “author.” Under a general rule, the first owner of copyright in a work is its author. Therefore, by default, architects are the authors of and first owners of copyright in their works: plans, drawings, specifications, addenda, and so on. If the architect is an employee, however, and creates work as part of their job, the “employer” instead of the “author” is the first owner of the copyright. The rules on ownership can also be changed by agreement. For example, an architect can agree that copyright will belong to the client. Copyright law requires that the agreement, or contract, be in writing. By default, however, the architect or architectural firm owns the copyright in the work, and the client’s fee, when paid, provides the client with permission to use the work.

A recent case confirmed that, by default, if the client does not pay the architect in full, the architect can revoke permission for the client to use the work.

Note: When an architectural practice engages an independent contractor (sometimes erroneously referred to as a “contract employee”), the copyright, by default, belongs to the independent contractor. There should be agreement on the issue of copyright ownership in order to avoid future problems.

Owning a Copy Does Not Include Owning Copyright

Ownership of a physical object (or digital file) does not include ownership of copyright. For example, ownership of a set of plans does not mean that a client also owns the copyright in them. Just because the client physically owns the plans does not mean the plans can be copied, used on a website or used to construct another building. The restrictions imposed by copyright law still apply, regardless of who owns a copy of the plans. Any use of the plans that are restricted by copyright requires the author or copyright owner’s permission. The client is entitled to the use of the “instruments of service” (usually the drawings and specifications but also feasibility reports, building condition assessments, and a host of other deliverables), but only on the condition that the client has paid for the services represented by the instruments of service, and then only for the purpose intended. Purposes intended should be clearly described in the client-architect agreement. The legitimate needs of clients should be dealt with in a written agreement and the agreed-upon uses of the copyright protected material should be clearly defined.

How Long Does Copyright Last?

Ownership of physical property, such as a car or piece of land, continues until the property is sold, consumed or given away. Copyright is different because it ends after periods of time set in the Copyright Act. Under a general rule, copyright subsists for the life of the author of the work, the remainder of the calendar year in which the author dies, plus an additional 50 years. Where an architectural work has more than one author, copyright subsists for the life of the author who dies last, for the remainder of the calendar year of that author’s death, plus an additional 50 years. When copyright ends, a work is said to fall into the “public domain.” Everyone is free to use a public domain work in whatever way they wish, including in digital form, without permission and without paying royalties.

What Rights Does a Copyright Owner Have?

The copyright law provides several legal rights. These rights permit copyright owners to control when, where, by whom and at what cost their creations can be used. There are two different kinds of rights: moral rights and economic rights.

Right of Reproduction

One of the most important economic rights an architect has under the Copyright Act is the sole and exclusive right to reproduce a work, or a substantial part of it, in any material form. An example of how this applies in an online setting is downloading. In copyright terms, downloading is making a copy. Downloaded copies are reproductions under copyright law and require the authorization of the copyright owner. As the author, an architect has the exclusive legal right to copy specifications, drawings, reports and addenda, and is the only person who can authorize anyone else to do so. Paper, electronic, or three-dimensional models are copies in material form. Although unauthorized use is not a new concern, the ease of copying electronic documents is a major issue for architects in the digital context.

Right of Publication

Another right provided is the exclusive right to publish the work for the first time. The decision of whether and when to publish plans belongs to the copyright owner.

Right of Adaptation

Another right is to adapt a work from one form to another. An example which clearly illustrates this right is adapting a novel to make a movie. Architects, like novelists, have the legal right to control adaptations of their works from one form to another. For example, an architect has the right to control adaptation of plans or drawings to serve a new purpose.

Right of Electronic Distribution

Architects also have the right to control communication of their work to the public by telecommunication. This includes the online display of works on publicly accessible websites as well as the offering of works online to the public for download. Only the copyright owner has the legal right to communicate to the public by telecommunication, or to authorize anyone else to do so. If anyone, such as a client or a contractor, wants to transmit an architectural work online, they have to get the authorization of the copyright owner. For example, virtual or electronic plans rooms cannot operate unless the authorization of the copyright owner in the electronic documents is first obtained. If authorization is not obtained, an infringement will occur. When an architect owns the copyright, they control the electronic use.

What Is Copyright Infringement?

“Infringement” is the legal word for breach or violation of copyright law. Infringement occurs when someone, without permission, does something only the copyright owner has the right to do, or to authorize. For example, only the copyright owner has the right to make a copy. When someone makes a copy, they infringe copyright because they do something only the copyright owner has a right to do. There are consequences for breaking the law. For example, the consequence of jay walking is a ticket, and for murder, a jail term. Infringement of copyright law is no different. The consequence for copyright infringement is a court order that money be paid by a defendant as compensation for damages caused by an unauthorized use of a copyright work. There are many cases where architects have been awarded money to compensate them for the unauthorized use of their work. The common consequence is an injunction (court order to stop infringement).

Copyright Notices

Copyright protection in Canada is automatic. Under the Copyright Act there is no need to register copyright in order to be protected, although there is a voluntary registration system administered by the Canadian Intellectual Property Office at Industry Canada. A copyright registration certificate entitles the registrant to presumptions on ownership and authorship which are useful in enforcing copyright against third parties. In Canada, it is not necessary to mark a work with a notice of copyright in order for it to be protected. However, a work must be marked for it to be protected in some other countries. An international agreement called the Universal Copyright Convention provides for marking with a small “c” in a circle, the name of the copyright owner and the year of first publication. An example is “© John Doe Architect, 2001.” Even though marking is not mandatory in Canada, it serves as a reminder to others that copyright exists in a work and gives the name of the copyright owner.

Digital Locks and Rights Management Information

Canadian copyright law was recently updated to provide protection for digital locks, such as password protection or anti-copying technology, and rights management information, such as watermarks or metadata. If access to a work is protected by a digital lock, someone who bypasses or removes the lock is liable as if they infringed copyright. Similarly, someone who removes rights management information in order to facilitate copyright infringement is liable as if they infringed copyright. There are a few limited exceptions to these rules. For example, a digital lock can be removed for law enforcement purposes. It is important to remember that, since software (such as AutoCAD) is protected by copyright, the bypassing or removal of digital locks that control access to that software is prohibited.

Users’ Rights

Canada’s copyright law also provides users of copyright-protected works with their own set of rights. These rights, such as “fair dealing,” enable people in certain circumstances to use works in ways that would otherwise infringe copyright. For example, a user may be permitted to make a copy of an architectural plan for non-commercial research without seeking the architect’s permission. The question of whether these rights are available typically depends on the specific circumstances at play, but in general, the rights enable uses that serve a publicly desirable goal and that do not interfere with the market for the works.

Trademarks and Patents

There are five types of intellectual property: copyright; patents; trademarks; industrial designs; and integrated circuit topographies. A trademark is a word, a symbol, a design, or a combination of these, which traders use to distinguish their wares and services from those of their competitors. Trademarks are owned by and come to represent not only actual wares or services but the reputation of the trader. Architects often have trademark rights since almost everyone that operates a business uses a trademark of one kind or another to identify their wares or services. A patent gives an inventor the right to exclude others from making, selling or using an invention for a maximum of 20 years. In exchange, the inventor provides a full description of the invention so that all Canadians can benefit from the advance represented by the invention. As a general rule, patent protection is not relevant to architectural practice.

Some Practical Suggestions1

The practical enforcement of copyright in an online environment has many aspects. It involves the control of files and material sent through e-mail, removable media, and downloads from host sites on the Internet. These are the general methods of transferring files between individuals, and usually lack any sort of control at either the base level, or in the distribution itself.

While it is important to explore and implement some type of copyright strategy, it is equally important to note that the single largest contributing factor to copyright infringement is general public attitude. Although this is slowly changing, the public’s attitude toward the digital world, and particularly the Internet, has been that it is essentially a “free” domain. Great resistance has been offered to any person or group attempting to institute a pay-for-use system on the Internet.

In this environment, control over copyright material becomes the responsibility of the copyright owner. Copyright laws exist, but unless infringement is blatant or causes enormous economic harm, enforcement will generally not occur. Infringement rarely is wildly obvious or causes millions of dollars in economic harm. This generally makes expensive litigation an undesirable option. From a practical perspective, there are several technological ways to minimize copyright infringement:

- A digital drawing can be bound, or its layers grouped into a single layer, which minimizes the usefulness of the drawing file.

- Use of software, such as Adobe Acrobat, creates a graphic file that is printable and viewable, but has no direct CAD usefulness.

- Files or material available for download from a web, ftp, or other accessible public site should be password protected.

- Include text in an e-mail message, with any removable media, and within the file itself, warning the user that the content of the file is protected by copyright and that copying is prohibited unless permission is obtained.

This list is by no means comprehensive but outlines some simple steps. None of these steps wholly, or even in large part, will stop copyright infringement. However, awareness of the fact of infringement may, in the long run, prove to be of the greatest value to architects in protecting their work.

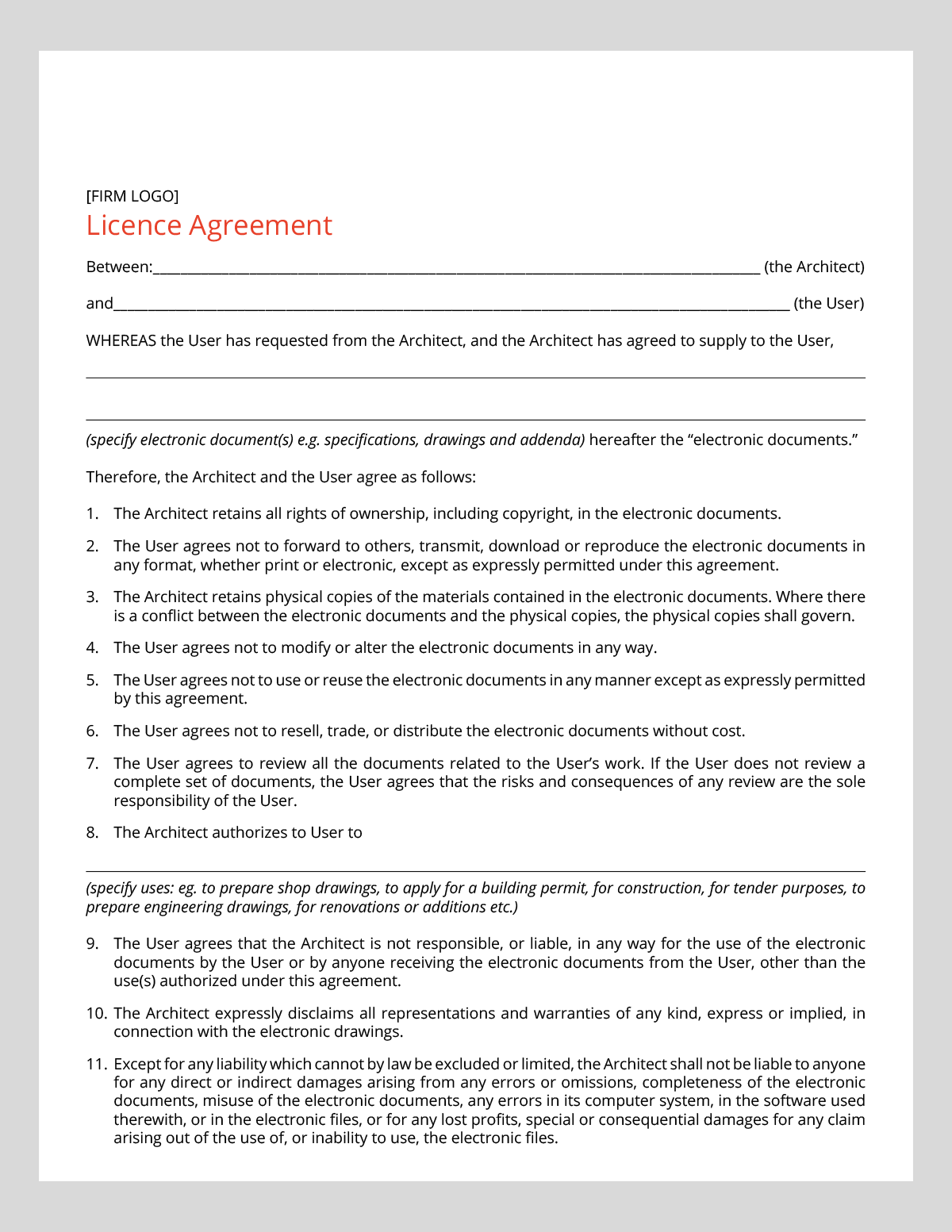

The following documents and forms are attached:

Licence Agreement – an agreement form to be completed and used when the architect intends to permit limited use of their documents. The architect should ensure appropriate compensation for such a licence.

Copyright Notice – sample wording to be applied to all electronic documents.

Disclaimer – sample wording to be applied to all electronic documents.

The purpose of these forms is to assist the architect in the overall control and management of electronic documents and in the protection of the architect’s copyright.

1Liberally adapted with permission from an article by Chris Gowling, Kasian Kennedy Architecture Interior Design and Planning.

Click for Full PDF Document