Définitions

Client : Une personne qui recourt aux services d’un professionnel.

Maître de l’ouvrage : La personne ou l’entité désignée comme telle dans la convention. L’expression englobe tout agent ou représentant autorisé désigné comme tel par écrit à l’entrepreneur, mais ne comprend pas le professionnel. (Définition du CCDC 2, Contrat à forfait.)

Introduction

On dit souvent qu’il n’y a pas de bonne architecture sans un bon client. Pour fournir une bonne architecture, l’architecte doit s’investir dans la création et le maintien de relations fructueuses avec tous les clients.

Les clients peuvent être des particuliers ou des multinationales, de grandes agences gouvernementales ou de petites entreprises du secteur privé, des promoteurs internationaux ou les occupants d’un bâtiment existant. On ne peut surestimer l’importance du client. Contrairement à un « consommateur » (une personne qui achète des biens ou des produits), un client achète des services professionnels. Le présent chapitre traite des différents types de clients et de leur relation avec l’architecte.

Le client

Le client est la personne ou l’organisme qui engage l’architecte pour fournir des services professionnels. Souvent, mais pas toujours, le client est également le propriétaire de la propriété sur laquelle le projet sera situé. Le client peut aussi être un design-constructeur, un gérant de construction ou un promoteur, mais tous les clients ont un point en commun : ils sont l’entité avec laquelle l’architecte conclut un contrat pour la prestation de ses services. Le client :

- choisit généralement les principaux participants, y compris l’équipe de conception et l’équipe de construction;

- paie généralement les coûts de la conception, de la construction et de l’exploitation subséquente de l’installation;

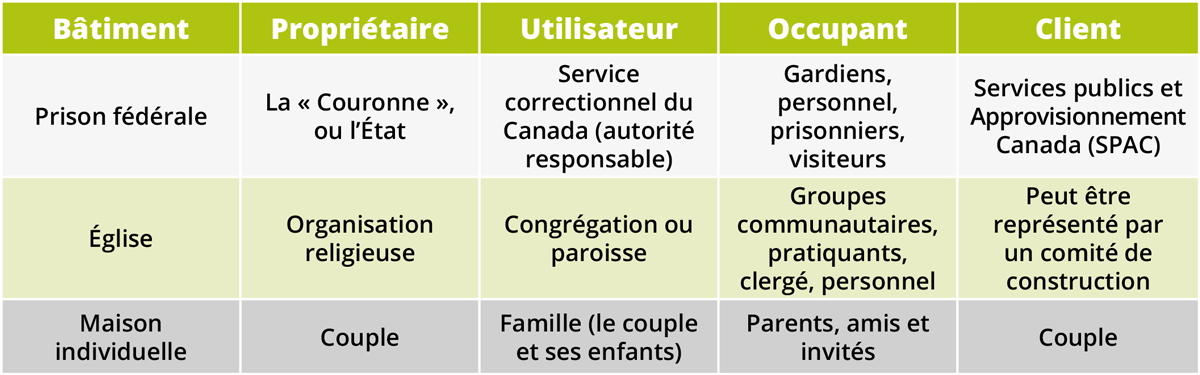

- peut être le propriétaire, l’utilisateur ou l’occupant du bâtiment, ou une combinaison des trois;

- peut participer avec d’autres parties à un processus de conception intégrée dès le début du projet;

- peut être un design-constructeur.

En plus de faire la distinction entre un maître de l’ouvrage, un utilisateur et un occupant, l’architecte doit tenir compte des exigences de chacun.

TABLEAU 1 Types d’organisations des clients

Propriétaires

Les propriétaires sont généralement les détenteurs du titre légal, du bail ou du permis d’occupation du terrain; du site ou du bâtiment existant; et du projet après son achèvement. Certains ordres d’architectes autorisent leurs membres à conclure un contrat pour fournir des services de conception à un agent du propriétaire. L’agent, par exemple un prestataire de services de gérance de projet, ne possède pas le titre légal du bien, mais agit dans l’intérêt du propriétaire pour réaliser le programme de conception et de construction.

Parties prenantes

En matière de gestion de projet, le terme « parties prenantes » désigne toute personne qui a un impact sur le résultat d’un projet ou qui peut être touchée par le résultat du projet. Les parties prenantes d’un projet de bâtiment comprennent évidemment les nombreuses parties potentielles que l’architecte doit gérer pour assurer la réussite du projet. Elles comprennent aussi les utilisateurs ou les occupants du bâtiment et bien d’autres parties. Les autorités compétentes, l’équipe de conception, le personnel de construction, le personnel du maître de l’ouvrage, etc. sont toutes des parties prenantes du projet. Chaque groupe peut avoir des niveaux d’intérêt et d’influence très différents dans le projet de bâtiment.

Les utilisateurs sont les groupes ou les personnes qui utilisent le bâtiment. Ils comprennent le ou les principaux locataires d’un bâtiment, ainsi que ses résidents et occupants et le public. Généralement, les utilisateurs s’intéressent aux éléments suivants du bâtiment :

- emplacement et sélection du terrain;

- durée de vie;

- design, notamment fonctionnalité, confort et sécurité;

- exploitation et entretien.

Les occupants sont les personnes qui occupent ou qui utilisent le bâtiment sur une base quotidienne. Ce sont par exemple les occupants des logements, les travailleurs, les locataires secondaires, les entreprises ou le grand public qui utilisent le bâtiment à titre de patients, de clients d’un restaurant, d’acheteurs, de touristes, etc. Il se peut que les occupants n’aient pas de participation directe dans la conception et la réalisation d’un projet de bâtiment.

Bien d’autres groupes peuvent être impliqués dans le projet de bâtiment, y compris :

- les gestionnaires du bâtiment ou les sociétés de gestion d’installations;

- les résidents, les voisins et les associations de contribuables;

- les institutions financières qui financent la conception et la construction;

- les autorités responsables;

- les gestionnaires de projets.

L’architecte doit répondre aux exigences de tous ces groupes tout en s’assurant de satisfaire aux exigences du client.

Voir le chapitre 5.2 – Gestion des parties prenantes pour en savoir davantage sur le rôle de l’architecte dans la gestion de l’engagement des parties prenantes dans les projets de conception.

Types de clients

Chaque client a sa propre personnalité, son style de fonctionnement et des attentes différentes par rapport à sa participation dans le projet. Les types de clients sont les suivants :

- les propriétaires immobiliers;

- les promoteurs;

- les entités de partenariats public-privé (divers modèles);

- les entreprises de construction;

- les firmes de gestion de projet engagées par le client à titre principal;

- les firmes de gestion de projet engagées par le client à titre d’agent et agissant comme représentantes du maître de l’ouvrage;

- les gouvernements et administrations publiques (fédéraux, provinciaux, territoriaux et municipaux);

- les institutions (installations publiques);

- les organismes à but non lucratif;

- les propriétaires de petites entreprises;

- les particuliers.

De manière générale, on peut séparer les clients en deux groupes principaux : ceux du secteur public et ceux du secteur privé. Ces deux groupes se distinguent par les types de projets de bâtiments qu’ils entreprennent et la source de leurs ressources financières.

Secteur public :

- responsable des projets de bâtiments destinés à l’usage du grand public et des employés, allant des écoles, des hôpitaux et des installations de recherche aux installations militaires;

- les ressources financières, qu’il s’agisse d’investissement en capital ou de biens loués, proviennent des impôts et des autres recettes du gouvernement ou de collecte de fonds.

Secteur privé :

- la provenance des projets de bâtiments va des propriétaires souhaitant rénover leurs maisons jusqu’aux sociétés immobilières qui désirent soutenir leurs activités commerciales ou industrielles. Ces projets comprennent des hôtels, des immeubles de bureaux, des centres commerciaux, des immeubles résidentiels à logements multiples et des installations industrielles;

- les ressources financières proviennent d’institutions prêteuses privées, comme les banques, les sociétés de crédit hypothécaire et les marchés de capitaux, ou des réserves de capitaux du propriétaire.

Entreprises

Les entreprises clientes sont :

- des entreprises du secteur privé constituées en sociétés;

- des entreprises à but non lucratif;

- des sociétés d’État.

Ces clients peuvent être de petites entreprises familiales ou de grands conglomérats multinationaux. La méthode de prise de décision, d’approbation des financements et de sélection des architectes peut varier considérablement d’une entreprise cliente à l’autre. En règle générale, une entreprise désigne un représentant qui assure la liaison avec l’architecte et gère le projet pour l’entreprise. Le représentant du client peut avoir une autorité limitée et relève généralement d’un comité, d’un conseil d’administration ou d’un président-directeur général. Il est parfois prudent d’obtenir une copie de la résolution du conseil d’administration qui attribue des pouvoirs au représentant du client.

Les entreprises clientes :

- peuvent être des clients avertis ayant une importante expertise à l’interne;

- peuvent n’avoir jamais participé à un projet d’architecture;

- peuvent comprendre des promoteurs qui s’y connaissent en processus de conception et de construction;

- ont tendance à être orientés vers l’entreprise;

- peuvent avoir des attentes élevées en matière de prestation de services et de rapidité d’intervention;

- peuvent ne pas avoir l’habitude d’utiliser les formules de contrat normalisées de l’industrie entre client et architecte et préférer utiliser plutôt des bons de commande ou des contrats internes.

Gouvernements et administrations publiques

Les clients gouvernementaux peuvent provenir de divers ordres de gouvernement – municipal, régional, provincial, territorial ou fédéral. Les procédures législatives et réglementaires, ainsi que la responsabilité de rendre des comptes au public, dicteront l’approche des clients gouvernementaux dans les projets de bâtiment. Le processus décisionnel est démocratique et généralement transparent, mais souvent très lent. Il est fréquent que les documents doivent subir de multiples examens et de longs processus d’approbation et les architectes devraient négocier leurs honoraires pour ces examens et approbations. Chaque organisation gouvernementale a ses propres exigences et sa « personnalité bureaucratique », et elle peut être divisée en plusieurs services. Les clients gouvernementaux, en particulier le gouvernement fédéral et les gouvernements provinciaux et territoriaux, sont généralement plus expérimentés et ont accès à un personnel professionnel et technique qui peut les aider dans la réalisation de leurs projets.

Le gouvernement fédéral et, de plus en plus, les autres ordres de gouvernement et certains organismes publics affichent leurs projets et leurs demandes de propositions sur des babillards électroniques centraux. Les architectes qui désirent obtenir des commandes publiques devraient consulter régulièrement de tels babillards, dont Merx, à www.merx.com.

Exemples de clients gouvernementaux :

- Services publics et Approvisionnement Canada (SPAC);

- Postes Canada ou Infrastructure Ontario (sociétés d’État);

- la municipalité régionale d’Ottawa-Carleton;

- la ville de Saint-Jean;

- le village de Saint-Joseph-de-la-Rive.

Les clients gouvernementaux ont fréquemment leurs propres formules de contrats. Voir le chapitre 3.8 – Gestion des risques et responsabilité professionnelle sur les pièges des contrats non normalisés.

Institutions

Les clients institutionnels reçoivent généralement des fonds du gouvernement, organisent des campagnes de financement, reçoivent des subventions, des dons ou des fonds provenant d’autres sources. Ce sont notamment des hôpitaux, des conseils scolaires, des musées et des organisations de services sociaux.

À certains égards, les clients institutionnels sont comme les clients gouvernementaux dans la mesure où ils peuvent avoir des méthodes similaires de sélection des architectes et avoir les mêmes exigences en matière de responsabilité (envers le gouvernement, les organismes publics de financement, les donateurs, les bienfaiteurs). Certains clients institutionnels n’ont pas de personnel professionnel ou technique. Parfois, des membres bénévoles de leurs conseils d’administration peuvent faire partie de comités de construction qui assurent la liaison avec l’architecte.

Exemples de clients institutionnels :

- Conseil scolaire de Calgary;

- Hôpital général du Lakeshore;

- Galerie d’art de Winnipeg;

- Société John Howard;

- Association de commerçants du centre-ville;

- Groupes de contribuables.

Les clients institutionnels ont fréquemment leurs propres formules de contrats. Voir le chapitre 3.8 – Gestion des risques et responsabilité professionnelle sur les pièges des contrats non normalisés.

Petites entreprises ou particuliers

Les clients propriétaires de petites entreprises et les particuliers sont souvent le maître d’ouvrage, l’utilisateur et l’occupant du bâtiment. Les propriétaires de petites entreprises qui ont besoin de locaux pour exercer leurs activités commerciales, ou d’améliorations locatives aux installations existantes, sont des clients typiques du secteur privé. Les particuliers, les couples et les familles qui souhaitent rénover une maison existante ou construire une nouvelle maison personnalisée sont également des clients typiques.

Le caractère informel des procédures, joint au manque d’expérience des clients, peut obliger l’architecte à plus de rigueur dans la préparation et la présentation de ses documents. Ces clients ont souvent besoin que l’architecte se fasse leur pédagogue et les guide dans le processus de conception et de construction de leur projet. On peut aussi ranger dans ce groupe les petits promoteurs et constructeurs, qui, toutefois, sont généralement mieux informés et plus exigeants.

Firmes de gestion de projets

Chaque projet doit être géré, et le rôle du gestionnaire de projet est essentiel à sa réussite. Le personnel interne ou les organisations sous-traitantes peuvent fournir des services de gestion de projet. Le mode de réalisation de projet connu sous le nom de « gérance de construction » est différent de la gestion de projet. Il est utilisé lorsqu’un maître d’ouvrage décide d’externaliser les fonctions de conception et de réalisation de projet. La firme de gérance de projet engagée sous contrat entretient des relations contractuelles avec les concepteurs et les constructeurs. Ce mode de réalisation existe depuis quelques années; toutefois, comme les organismes se concentrent de plus en plus sur leurs objectifs stratégiques et qu’ils externalisent la création et la gestion de leurs immobilisations, sa popularité s’est accrue et un nouveau type de groupe de clients est apparu, à savoir les firmes de gestion de projets.

L’externalisation de la réalisation du projet et la cession des risques du projet par le maître d’ouvrage peuvent entraîner des occasions d’affaires et des défis pour les architectes. Les maîtres d’ouvrage ne disposent pas toujours des ressources internes nécessaires pour gérer leurs programmes d’immobilisations, et l’embauche d’une firme de gestion de projets peut alors être une décision d’affaires prudente, car le maître d’ouvrage se concentre sur les compétences de base, laissant à la firme de gestion de projets le soin de faire ce qu’elle fait le mieux. Toutefois, lorsque les objectifs du maître d’ouvrage ne correspondent pas aux objectifs d’affaires de la firme de gestion de projets, l’architecte se voit confronté à des défis particuliers. Comme c’est le cas dans les projets de design-construction, l’architecte ne travaille pas directement pour le maître d’ouvrage, mais plutôt pour un intermédiaire dans la chaîne de valeur de la réalisation du projet. Les compromis en matière de conception, de qualité et d’étendue des services peuvent donner lieu à des relations contractuelles stressantes.

Voir le chapitre 4.1 – Modes de réalisation des programmes de conception-construction pour de l’information additionnelle.

Relations avec les clients

Responsabilités professionnelles et attentes des clients

Il est important que l’architecte comprenne son client et les motivations qui l’amènent à vouloir construire un bâtiment et qu’il établisse des lignes de communication régulières, cohérentes et claires avec celui-ci. L’architecte doit définir et décrire clairement le processus de conception et de construction afin d’éviter des attentes irréalistes. Il ne doit pas se soumettre à des exigences erronées du client ni omettre de l’informer des problèmes éventuels du projet et de leurs conséquences. De plus, l’architecte doit élaborer et analyser toutes les options, et obtenir le soutien et l’approbation du client pour la solution d’un problème.

Comme il a retenu les services d’un professionnel, on suppose, et la jurisprudence l’a d’ailleurs confirmé, que le client n’a pas de connaissances en construction et qu’il dépend par conséquent des conseils du professionnel, en l’occurrence l’architecte. Quand il traite avec son client, l’architecte doit exercer à tout moment son jugement professionnel.

Les clients n’ont pas tous le même degré de participation dans les projets d’architecture et n’ont pas tous les mêmes attentes par rapport au rôle de l’architecte. Dans certains cas, l’architecte a beaucoup de latitude et d’autonomie; dans d’autres, son rôle est très étroitement défini et il ne peut soumettre que quelques recommandations. Savoir entretenir de bonnes relations avec le client et s’adapter à sa personnalité n’est pas différent de la gestion des relations interpersonnelles en général ni de la gestion des ressources humaines.

Voir le chapitre 5.2 – Gestion des parties prenantes.

Contrats client-architecte

Lorsqu’il fournit ses services professionnels, l’architecte devrait toujours avoir un contrat écrit qui décrit :

- les services fournis;

- les honoraires correspondants;

- l’échéancier de la prestation des services, y compris la date prévue de l’achèvement de la construction du projet;

- les diverses conditions et modalités qui régissent le contrat (y compris les obligations du client).

Dès le début du projet, l’architecte doit expliquer clairement au client ce qui est compris dans le contrat et ce qui ne l’est pas. La plupart des différends surviennent à la fin du projet et découlent d’une divergence dans les attentes des deux parties au contrat.

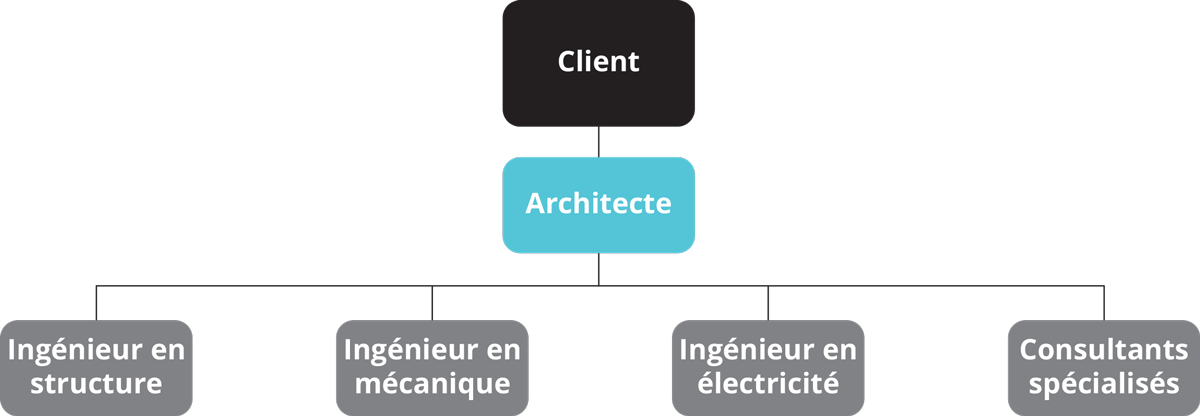

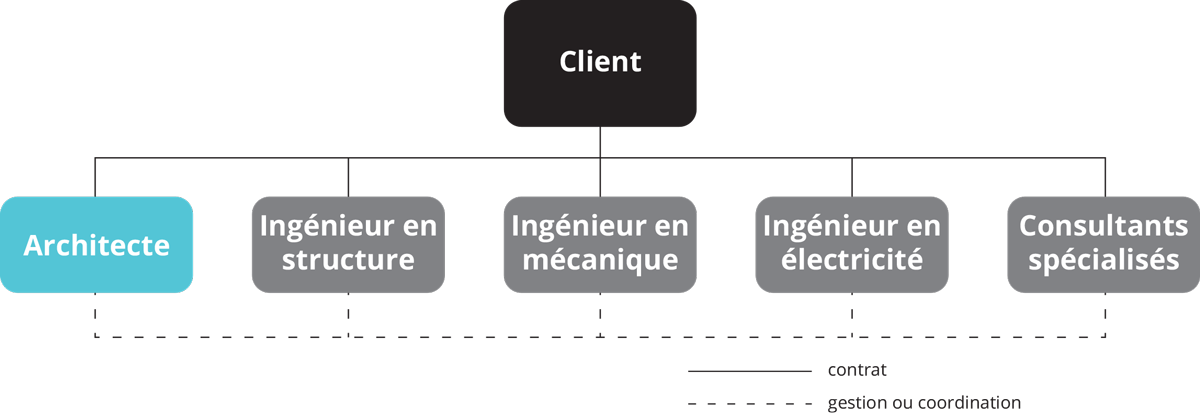

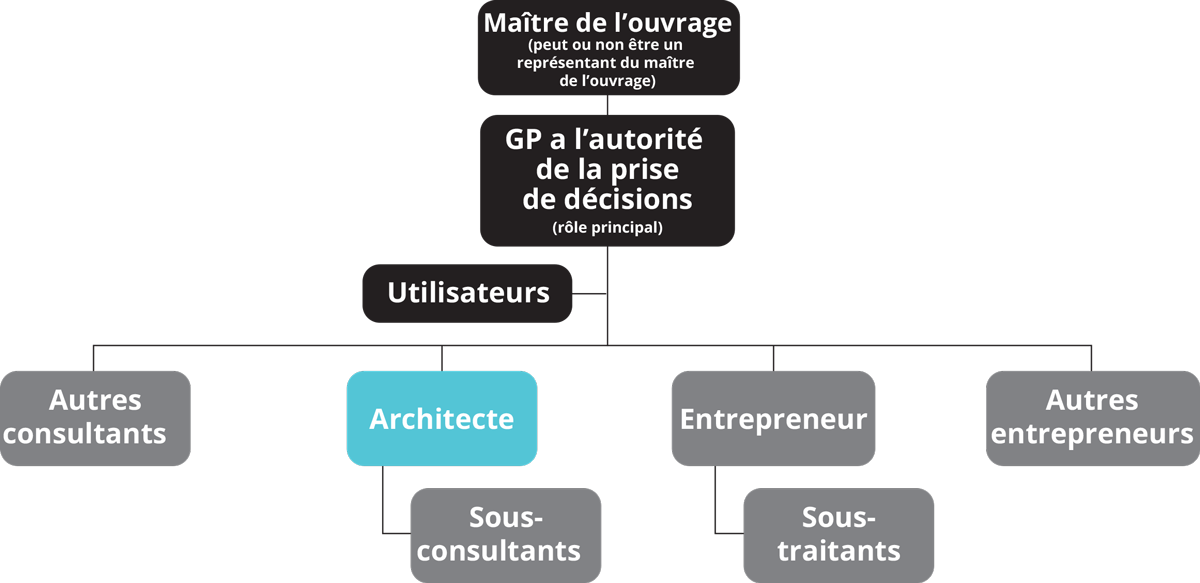

La Formule canadienne normalisée de contrat pour les services de l’architecte, le Document Six, décrit certaines responsabilités du client. Le client peut décider de retenir les services de l’architecte comme principal professionnel et lui confier le mandat d’engager les ingénieurs et autres conseils et consultants (voir la Figure 1). Il peut aussi engager les ingénieurs directement et séparément en concluant des contrats distincts. Dans ce cas, l’architecte doit s’assurer que le client comprend bien l’étendue de ses services et qu’il accepte de lui verser des honoraires pour la coordination et la gestion des ingénieurs et autres experts-conseils et consultants (voir la Figure 2).

Obligations

Tout au long du projet, l’architecte devra peut-être rappeler au client qu’il doit fournir avec une célérité raisonnable diverses informations et approbations, notamment :

- un programme (voir le chapitre 6.1 – Études préconceptuelles);

- un budget de construction.

Le client, en tant que propriétaire de l’installation, y compris le bâtiment et le terrain, réalise les avantages de la propriété des actifs et, inversement, le client doit assumer la responsabilité du risque associé à la propriété des actifs. Il incombe donc au client de fournir à l’architecte les informations requises pour la prestation de ses services professionnels, notamment :

- la description légale, les levés topographiques et l’emplacement des services sur le terrain;

- un ou des rapports sur l’état du bâtiment existant;

- des tests de détection de substances désignées (plomb, amiante, BCP, etc.);

- les études géotechniques,

- le rapport de l’évaluation environnementale.

Cette liste n’est pas exhaustive et l’architecte aidera le maître de l’ouvrage à cerner l’information nécessaire et aidera le client à retenir les services des spécialistes appropriés pour procéder aux études et aux évaluations et préparer les rapports.

Il est fortement déconseillé à l’architecte de retenir les services de consultants pour procéder à ces diverses études et investigations, car il pourrait ainsi engager sa responsabilité de manière disproportionnée en plus de prendre en charge des services qui ne sont pas liés à la prestation de services professionnels d’un architecte. Il est plutôt conseillé à l’architecte de discuter de la possibilité de retenir les services de consultants tels que les ingénieurs géotechniques et les arpenteurs-géomètres avec son assureur de responsabilité professionnelle.

Représentant du client

Pour que l’architecte reçoive des instructions claires et non contradictoires de la part du client, il faut qu’une seule personne les lui donne. Toute autre façon de procéder ne peut être que source de confusion et d’inefficacité : c’est le cas, par exemple, lorsque chaque membre d’un comité de construction créé par le client communique individuellement avec l’architecte pour lui faire part de ses attentes.

Les formules de contrat normalisées précisent que l’une des obligations du client est de nommer un représentant ou « d’autoriser, par écrit, une personne à agir en son nom et de définir l’étendue des pouvoirs de cette personne, au besoin » (Formule canadienne normalisée de contrat pour les services de l’architecte – Document Six 2018). Les clients experts, c’est-à-dire ceux qui participent de façon importante au processus de construction, ont souvent un ingénieur ou un architecte comme représentant. Les autres, tels les clients du secteur privé ou les clients individuels, peuvent agir sans représentants. Les comités de bénévoles peuvent nommer une personne pour assurer la liaison avec l’architecte. Il est important de nommer le représentant du client dès le début du projet.

FIGURE 1 L’architecte comme professionnel principal

Il existe divers autres modes de réalisation de projets, notamment le design-construction, la gérance de construction et les partenariats public-privé. La relation entre l’architecte et le client varie considérablement selon le mode de réalisation du projet. Voir le chapitre 4.1 – Modes de réalisation des programmes de conception-construction.

FIGURE 2 Contrats multiples et distincts entre le client et les professionnels et consultants spécialisés

Lorsque le client conclut plusieurs contrats distincts, l’architecte doit s’assurer que ses responsabilités de coordination de l’équipe d’experts-conseils et autres consultants de conception et de leur travail sont bien comprises par le client.

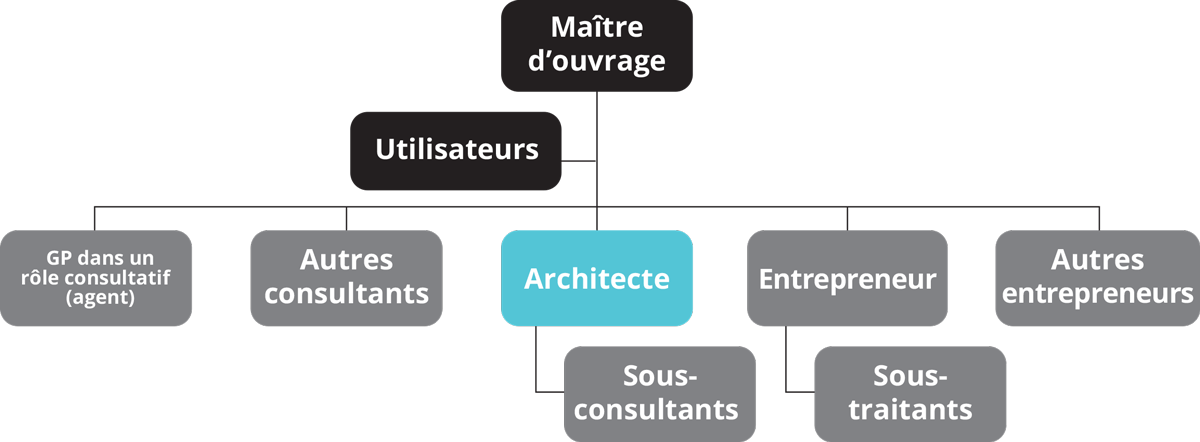

Le maître de l’ouvrage peut sous-traiter la responsabilité de la planification et de l’exécution d’un projet à une tierce partie qui peut jouer un rôle « d’agent » ou un rôle « principal ». En tant qu’agent, cette partie joue un rôle consultatif auprès du maître d’ouvrage, en lui fournissant des conseils, en assurant la surveillance, le suivi et le contrôle du projet et en agissant comme son représentant. Le projet peut alors être réalisé en mode conception-offres-construction, ou en mode gérance de la construction. Le maître d’ouvrage entretient une relation contractuelle avec l’architecte en tant que consultant principal, ou conclut plusieurs contrats, un avec chaque firme d’experts-conseils ou de consultants. Le gestionnaire de projets est un intermédiaire dans les relations contractuelles du maître d’ouvrage avec les consultants en conception et les constructeurs et il peut exercer une forte influence sur la prise de décision du maître d’ouvrage.

FIGURE 3 Organisation d’un projet lorsque la firme de gestion de projets agit comme « agent ».

Lorsque cette tierce partie joue un rôle « principal », c’est que le maître de l’ouvrage lui a transféré la responsabilité de la réalisation du projet et des risques du projet. On l’appelle alors le « gérant de construction ». C’est lui qui conclut des contrats avec les professionnels de la conception et les entrepreneurs chargés de la construction et non pas le maître de l’ouvrage. Dans cette structure organisationnelle de projet, le gérant de construction joue le rôle principal et l’architecte entretient avec lui une relation semblable à celle qu’il a avec un design-constructeur.

FIGURE 4 Organisation d’un projet lorsque la firme de gestion de projets joue le rôle « principal »

Sélection d’un architecte

Les clients peuvent utiliser diverses méthodes pour retenir les services d’un architecte. Ils peuvent le faire sur la base d’une relation établie, parce qu’ils aiment sa sensibilité au design, parce que l’architecte offre une proposition de valeur attrayante, comme « un soutien au client exemplaire », ou pour d’autres raisons. Ils peuvent sélectionner l’architecte dans le cadre d’un processus concurrentiel, comme un concours d’architecture, une demande de propositions (DP) ou un concours pour être inscrit à une liste de demandes d’offre à commandes (DOC).

Processus d’approvisionnement générique

Le processus d’acquisition concurrentiel des services d’un architecte suppose une série d’étapes largement adoptées par les clients des secteurs public et privé :

- Planification :

- planifier les services qui seront requis et le mode d’approvisionnement;

- élaborer la documentation requise pour décrire les services nécessaires;

- élaborer les critères de sélection et le mode d’évaluation.

- Sélection d’une firme :

- identifier des firmes potentiellement aptes à offrir les services en publiant un appel à manifestation d’intérêt ou en créant une liste basée sur des références de sources connues;

- distribuer les documents d’approvisionnement à des sources potentielles et fournir de l’information additionnelle sur demande des firmes;

- recevoir les propositions des firmes élaborées sur la base des exigences du client pour la prestation des services et l’évaluation des propositions;

- évaluer les propositions et sélectionner la firme préférée;

- attribuer le mandat de conception, possiblement après négociation.

Les clients suivront ce processus générique pour retenir les services d’un architecte et y apporteront des variantes selon la complexité du projet et les exigences du client en matière d’information sur la firme et ses capacités. Pour un projet peu complexe pour lequel l’étendue des travaux est relativement petite, le client demandera seulement des renseignements de base et une proposition à prix forfaitaire dans le cadre d’un processus en une seule étape. Pour des projets plus complexes, la demande de propositions demandera une quantité importante d’information, notamment :

- un volet technique :

- historique de la firme;

- expérience de projets antérieurs et références;

- capacités et expérience des personnes responsables du projet;

- approche envers l’exécution du mandat de conception; et possiblement un plan de gestion du projet;

- une proposition d’honoraires.

Le processus peut comprendre une étape supplémentaire d’entrevue en personne au cours de laquelle la firme peut présenter son travail et le client peut poser des questions spécifiques, souvent sur la base de la proposition reçue.

Le client peut demander que la firme présente des croquis du projet lors de cette entrevue. La présentation de travaux de conception avant l’attribution de la commande (services gratuits, en d’autres termes) est considérée comme une pratique non professionnelle et, dans certains ordres d’architectes, peut donner lieu à un constat de faute professionnelle.

L’évaluation de la proposition de la firme peut comporter plusieurs étapes. Le client utilise généralement un système de points pour évaluer les propositions. Il peut d’abord examiner le volet technique de la proposition et ensuite, si la firme reçoit une note technique minimale, examiner la proposition d’honoraires. Si la firme n’obtient pas la note minimale dans le volet technique, aucun autre examen n’est effectué et l’enveloppe contenant la « proposition d’honoraires » n’est pas ouverte.

Voir l’Annexe B – Lignes directrices et listes de contrôle : Demande de propositions (DP) pour un supplément d’information.

Concours d’architecture

Dans le cadre d’un concours d’architecture, le client étend les exigences et demande d’inclure à la proposition la création d’une ou de plusieurs solutions de conception. Le client qui décide de procéder à un concours d’architecture doit rémunérer toutes les firmes participantes. Les concours d’architecture doivent être sanctionnés par l’ordre d’architectes de la province ou du territoire où il se tient pour s’assurer que tous les participants reçoivent une compensation appropriée et que les règlements ne sont pas enfreints.

Pour un supplément d’information sur les concours d’architecture, voir le site Web de l’IRAC :

https://raic.org/fr/raic/concours-darchitecture-introduction

Sélection basée sur les compétences (SBC) ou basée sur la qualité

Une autre variante du processus de sélection est l’examen des propositions techniques avec la possibilité d’une entrevue en personne. Les propositions reçues sont classées selon leurs mérites techniques uniquement. Le client engage ensuite des négociations financières avec la firme qui s’est classée au premier rang. Ce processus exige que le client ait établi un budget pour les services de conception, avec un montant maximum pour les honoraires. Si le client et la firme s’entendent sur des honoraires qui se situent dans la fourchette d’honoraires préétablie par le client, la firme obtient le contrat. S’ils ne parviennent pas à s’entendre, le client peut mettre fin aux négociations sans pénalité et entamer des négociations avec la firme qui s’est classée au deuxième rang.

Certains organismes clients du secteur public croient qu’ils sont tenus par la réglementation d’inclure une proposition d’honoraires dans l’évaluation initiale des propositions pour l’approvisionnement en services professionnels. Certains vont même jusqu’à dire qu’ils n’ont pas d’autre choix que d’accepter la proposition aux honoraires les plus bas, indépendamment de la capacité ou de la complexité du projet. L’avantage de la sélection basée sur les compétences (SBC) ou de la sélection basée sur la qualité est que l’évaluation et la négociation sont basées sur la meilleure valeur offerte au client, plutôt que sur les honoraires les plus bas. La méthode de la SBC est largement pratiquée aux États-Unis et son utilisation se développe au Canada.

Pour un supplément d’information sur la SBC, voir : https://raic.org/fr/raic/la-s%C3%A9lection-bas%C3%A9e-sur-les-comp%C3%A9tences-sbc et https://www.oaa.on.ca/oaa/assets/images/bloaags/text/final_qbs_report_sep_1_2018.pdf.

Voir le chapitre 3.4 – Marque, relations publiques et marketing pour de l’information additionnelle sur la création d’une marque pour votre firme et sur le marketing de cette marque dans le marché.