Definitions

Corporation: A legal business entity formed by a group of people which acts as a single unit. A legal instrument is required to create the entity as a commercial corporation.

Joint Venture: A defined business relationship between two or more architectural practices for a limited purpose or objective, without some of the inherent duties and responsibilities of a partnership.

Partnership: An unincorporated relationship between architects (or other professionals, as may be permitted by provincial requirements) for carrying on business in common.

Sole Proprietorship: An architectural practice owned and controlled exclusively by one person.

Introduction

Architects decide to set up their own practices for many different reasons. Some of these include:

- the desire to control one’s own professional destiny;

- the motivation to provide service to society and to clients;

- the wish to specialize in a certain field of architecture or market niche;

- an offer to form a partnership or purchase shares from an established firm or colleague;

- the award of a significant commission, either through a competition or from a business associate;

- a means for creating work or employment.

Anyone considering such a change should be aware from the outset that establishing an architectural practice has serious implications for one’s personal, professional and business life. The individual should carefully weigh all the implications before embarking on this course.

Establishing and maintaining an architectural practice demands certain skills. The owner(s) of an architectural practice must be able to:

- develop and market a firm’s value proposition, attract clients, and sell services;

- negotiate terms and compensation in client-architect agreements;

- hire and manage qualified staff;

- perform the full range of architectural services efficiently and effectively;

- work with the construction industry and administer contracts;

- operate profitably and provide stability to the practice.

The first key steps in launching a practice are to assess one’s own abilities, set long-term goals, and develop a business model, business plan and strategic plan.

Styles of Architectural Practices

Many organizations develop a mission statement which helps to ensure that all members of the organization focus on the goals established in the strategic plan.

The mission statement should define the style of practice, to a certain extent. Three common generic styles as described by The Coxe Group are:

- Strong-idea (brains) firms, which are organized to deliver singular expertise or innovation on unique projects. The project technology of strong-idea firms flexibly accommodates the nature of any assignment, and often depends on one or a few outstanding experts or “stars” to provide the last word;

- Strong-service (gray-hair) firms, which are organized to deliver experience and reliability, especially on complex assignments. Their project technology is frequently designed to provide comprehensive services to clients who want to be closely involved in the process;

- Strong-delivery (procedure) firms, which are organized to provide highly efficient service on similar or more routine assignments, often to clients who seek more of a product than a service. The project technology of a delivery firm is designed to repeat previous solutions over and over again with highly reliable technical, cost and schedule compliance.

– excerpt from the book Success Strategies for Design Professionals by The Coxe Group, Inc.

However, a “style” of architectural practice is a profile of a set of factors that combine to create an overall image of the firm. Detailed planning is required to create a profile that is both unique and recognizable in the marketplace. The style defines the “value proposition” of the firm – the way it differentiates itself from others. As the firm evolves, it may exhibit a combination of two or more of these styles.

Business Model, Business Plan and Strategic Plan

The business model, business plan and strategic plan are three related but different documents. Each has a distinct purpose and the three build a complete perspective of the business.

Business Model

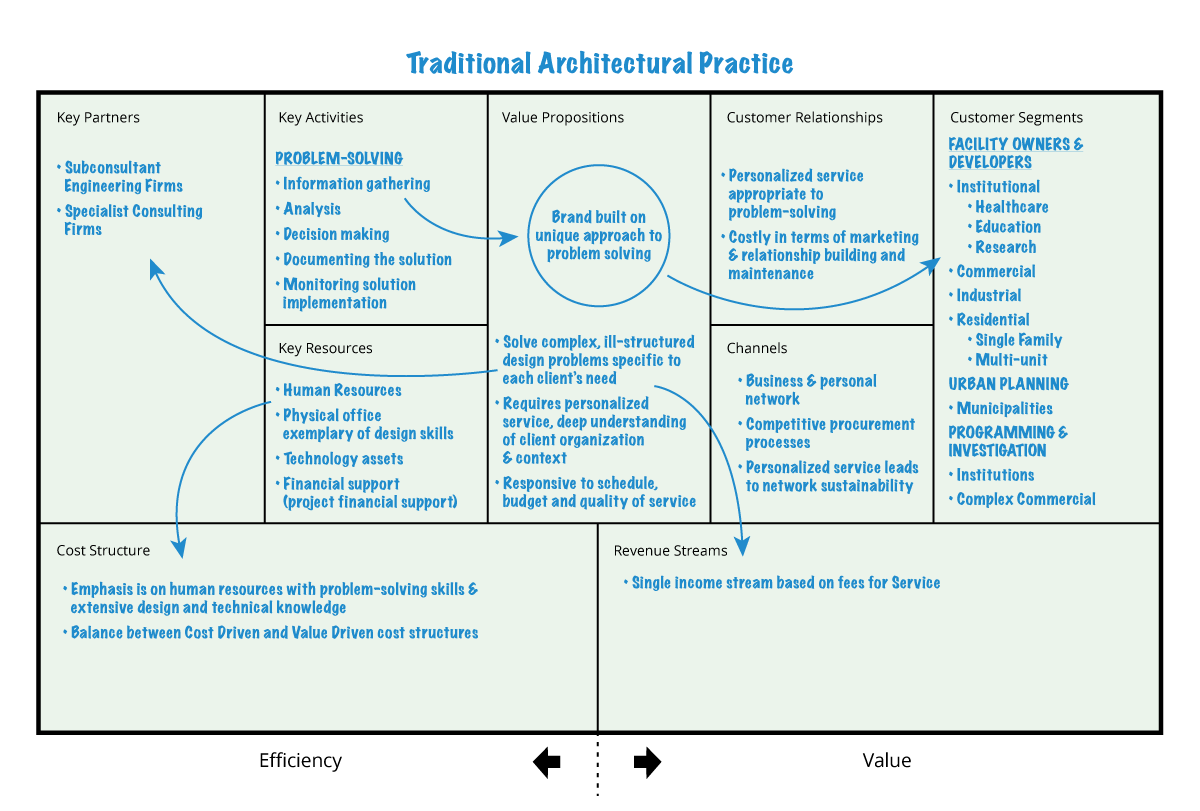

The business model is a description and illustration of what value the business will offer the marketplace, how a business will serve clients and generate income, and what resources and partnerships are needed to provide services.

Architectural firms employ a variety of business models in creating and managing their resources and capital assets. Relying solely on a traditional owner/client relationship as a business model may result in architects losing their influence in the design-construction-operation supply chain. Like all industries, architectural design services must explore innovative ways of doing business through new types of value generation for clients, forming new partner relationships, and exploring opportunities for enhancing both the efficiency and effectiveness of service delivery, and alternative income streams. The business model precedes both business planning and strategic planning.

The business model canvas approach developed by Alex Osterwalder provides both a process and tools for exploring from the ground up how a firm approaches doing business and generating value, rethinking traditional systems and assumptions, and focusing on what is important in service delivery.

The business model canvas is comprised of nine components:

FIGURE 1 Business model canvas, adapted from “Business Model Generation” by Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur.

As an example of the value proposition, a firm might look at generating value for clients using a business model that focuses on sustainable and regenerative design that requires much higher levels of collaboration among a larger project team.

The value of the architect in the role of facilitator should be explicitly stated in a value proposition – a value proposition that places a strong focus on programming, and client and stakeholder engagement. Emphasis on broader consultation and increased use of technical support early in the project may require different key resources and activities, and non-traditional project partners. Imagine a business model for an architectural practice that incorporates the following strategies to achieve high-performing sustainable design outcomes:

- leadership through information dissemination and facilitation;

- scenario planning and analysis;

- imagination in programming and templating for production;

- regular research supporting ideation and documentation;

- knowledge management through structured systems supported by corporate memory;

- evidence-based decision making;

- use of generalists and supporting specialists;

- attention to program over form, while recognizing the formal potential of understood building patterns.

Many firms have adopted the use of building information modeling (BIM) as an enhanced technology supporting visualization of design and increased efficiency in production. However, the most significant value of BIM is the integration of the design-construction industry supply chain with the potential for transparency of information flow along the chain. This may result in accelerated project delivery when alternatives to the traditional predictive project planning methods are applied. Rethinking how an architecture firm addresses value creation and repositioning itself in an integrated supply chain is best done through innovating a new business model.

Refer to additional business modeling and value proposition creation references at the end of this chapter.

The business model canvas is a tool to assist the architect in identifying value that will attract clients and expand the practice’s client base in a number of ways, including:

- specializing in a field of expertise or in a building type;

- developing new markets through expanding client channels, developing new client relationships, or identifying new client segments;

- providing additional value through pre-design or post-construction services to encompass the life cycle of a facility;

- forming partnerships with non-traditional groups or individuals who are not normally aligned with architects.

Business Plan

The business plan applies the knowledge gathered through business modeling and presents a detailed description of the firm’s proposed structure, income-generating potential, and resource needs, including financial, human and technological. The business plan is a start-up document with a defined and short-term timeframe, perhaps the first year. It is used to demonstrate to a firm’s partners in business, such as financial backers and suppliers of key resources, that the firm can attract clients, generate income, realize profit, and meet its commitments.

The business model describes services and deliverables that an architect thinks their proposed client segments will find attractive, and how they intend to create and deliver them. The business plan describes the operational systems that the firm will put into place to deliver those products and services. The business plan describes, in concise and accurate terms, the result of research, demonstrating projected income, costs, a list of needed resources and their costs, projected cash flow, how the business is going to attract clients and secure commissions, and a timeline towards profitability.

The business plan provides answers to hard, real-world questions. It may take some time for an emerging proprietor to complete the research needed and create a valid business plan. One of the most difficult aspects may be finding and securing those first initial commissions that will support the practice in the first year. An invaluable resource in this process is a client-champion who values an architect’s past work, appreciates their design vision, agrees with their approach to project management, and likes them.

An established firm will likely have to revisit its business plan on an ongoing basis. It is an evolving document that develops with the firm over time.

There are many resources available to support business plan development, as well as consultants who specialize in helping professional services firms. Financial institutions and entrepreneurial centres offer planning services, tools and templates, and small business financial packages to support their clients with business planning.

See “Appendix A – Business Plan Outline” at the end of this chapter for a list of the parts of the business plan.

Strategic Plan

Rena Klein’s table of contents for a business plan, see Appendix A, is just one example that may demonstrate a combination of business plan and strategic plan. It also presupposes that the goal of the firm in her example is growth from a small to medium-sized firm. One of the most important factors that drives a firm to develop a strategic plan is the need to extend the management of the practice beyond the reach of the sole practitioner, either through partnership, when multiple owners must agree on the strategic direction and managerial approaches, or when employees are charged with management responsibilities.

Where the business plan is a shorter-term document created to initiate an architecture firm, the strategic plan presents a management strategy that will guide a firm into the three- to five- and even 10-year horizon.

Strategic planning is a structured process that results in a clear articulation of a firm’s mission and purpose in delivering professional services, its vision for the future, and the measures that the firm needs to take to realize sustainable success in the long, medium, and short term. The strategic plan is a design for the firm’s future. It is a document that details the management decisions and actions that need to be taken, and maps a course for the development of an architectural practice in clear, concise terms. It should identify the following:

- the mission and values of the practice;

- a vision for the future of the practice;

- how those values align with the client segments it seeks to attract in the marketplace;

- the architectural practice’s value proposition(s) that describes its unique offerings;

- the actions needed to acquire resources, attract partners, and innovate;

- measurable long-, medium- and short-term goals.

It is common for firms to undertake a SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) as part of their strategic planning process.

The alternative to strategic planning is allowing external events to unfold and influence or control a firm’s direction. Rather than searching for specific opportunities that align with a firm’s purpose and capabilities, picking up opportunities as they arise results in the instability that accompanies unplanned growth or contraction, and vulnerability to market forces.

Strategic planning is a process that requires the business savvy, market intelligence, and leadership of the firm’s leaders. There is no single correct process for strategic planning. Useful tools and techniques can be found in many sources, including the business model canvas. Professional services consulting firms can facilitate strategic planning processes and provide their own tools and techniques to assist the firm’s leaders in preparing their strategic plan.

Typically, a strategic plan encompasses a timeframe of three to 10 years and it should be updated continually. In addition to the elements identified above, the plan should also address the following issues:

- a value proposition(s) effectively and efficiently delivered through channels to targeted client segments;

- a financial plan that includes its revenue stream projections and cost structures;

- a description of the key resources, including human resources and technology systems, key activities that generate value, and strategic partnerships;

- the process and timeframe for strategic plan review.

In certain instances, a succession plan or risk management may be appropriate.

The key resource required for strategic planning is the discipline to set aside the tasks and demands of day-to-day activity and maintain a focus on the future. There are a variety of tools and techniques readily available to support the various stages of developing a strategic plan. Some are quite simple to use but may require skilled facilitation to tease out underlying causes of problems, see through the superficial, and dare to think beyond the immediate challenges. The list below includes only a few of many common information gathering and analysis tools that are useful in a strategic planning process. See the list of references in this chapter for additional resources.

Brainstorming:

- Freely creates ideas and generates innovation without analysis or criticism;

Affinity analysis:

- Organizes ideas into thematic groups;

SWOT analysis:

- Examines an organization’s internal strengths and weaknesses and external opportunities and threats;

SOAR analysis:

- Examines an organization’s strengths and opportunities, aspirations and results;

GAP analysis:

- Examines the current situation, the desired situation, and the obstacles that lie in the path between those two.

Types of Ownership of an Architectural Practice

Architectural practices are structured according to size and complexity. Frequently, a practice will start as a simple entity, such as a sole proprietorship, and perhaps later evolve into a more complex legal structure, such as a corporation, or partnership of corporations. Several factors affect the type of ownership, including relationships with professional colleagues, tax implications, and exposure of personal assets. Architects should seek legal and accounting advice before structuring a practice, as well as confirm ownership regulations with the provincial or territorial regulator.

All business relationships should be based on a written agreement. Business partners should share certain values and financial goals, and architects are no exception. For partners or shareholders, a well-structured agreement provides a vehicle to deal with expansion, difficulties and disagreements, as well as disasters. Obtaining professional advice from a lawyer and an accountant in preparing an agreement that outlines the ownership of an architectural practice is essential. The structure of the practice must comply with the various architects acts and regulations of the provincial or territorial associations of architects, as well as with other business regulations.

See Appendix E – Charts: Comparison of Practice Requirements of Each Provincial or Territorial Association in Chapter 1.6 – The Organization of the Profession in Canada.

Sole Proprietorships

A sole proprietor is a single, unincorporated owner of an architectural practice. This architect has full personal control over all aspects of the practice. A sole proprietor can range from someone with a small, home-based office practice to an architect who employs many professionals and paraprofessionals. Most architectural practices in Canada are sole proprietorships.

See Chapter 3.3 – Brand, Public Relations and Marketing for information on marketing architectural services.

Partnerships

A partnership is comprised of two or more partners. Most provincial and territorial associations impose restrictions on whom an architect may form a partnership with.

See Appendix E, – Chart C: Comparison of Provincial or Territorial Requirements Regarding Partnerships, in Chapter 1.6 – The Organization of the Profession in Canada.

A partnership may include “associates”; however, only the partners bear personal responsibility for the control and liabilities of the practice. Each partner is both jointly and severally liable for the partnership’s full obligations. Because a partnership is a complex form of ownership, its terms should be spelled out in a partnership agreement. For items to include in a partnership agreement, see Appendix B – Checklist: Issues to Consider for Partnership Agreements at the end of this chapter.

Corporations

A corporation is a legal, collective entity authorized by statute to act as an individual business unit. Most provincial and territorial associations of architects have regulations that restrict the share ownership and the qualifications of directors of architectural corporations. Provincial and territorial architectural associations have different requirements for corporation setups. See Appendix E – Chart D: Comparison of Provincial or Territorial Requirements Regarding the Ownership and Structure of Corporations Which Practise Architecture in Chapter 1.6 – The Organization of the Profession in Canada.

Incorporating a practice is done for a variety of reasons, including to provide a means for a group of people to act as a single entity, and to manage taxation. Legal and accounting advice should be sought before forming a corporation and entering into a shareholders’ agreement. For items to include in a shareholders’ agreement, see Appendix C – Checklist: Issues to Consider for a Shareholders’ Agreement for Architectural Corporations at the end of this chapter.

Partnership of Corporations

A partnership of corporations is an architectural practice structured to preserve the individual identity of two or more corporations. There are a variety of reasons for creating this form of business entity. Such an entity:

- enables individual architects who are incorporated for business or tax reasons to practise with both the advantages of a partnership and the advantages of their corporation;

- allows two or more corporate practices to retain separate identities for certain types of projects but to join forces for other types of projects;

- allows the bringing together of complementary but differing interests and ownership – for example, one corporation may focus on architectural services, while the other is a corporation providing support through drafting services, equipment, real estate and other chattels, etc.

Joint Ventures

Joint ventures are usually formed by two or more firms to create one architectural entity for the purpose of a single specific project. Frequently, a joint venture is set up to provide complementary services for a particular project – for example, a practice specializing in hospital work may need to team up with a firm located near the site of the project to provide contract administration services, especially field review.

Joint venture projects may require special liability insurance, often on a single-project basis, to protect the parties forming the joint venture. Architects contemplating working in a joint venture should review the circumstances with their professional liability insurers to determine the most appropriate insurance arrangements. Clients may require the participants of a joint venture to obtain single-project insurance with higher limits than the practices carry through their annual practice insurance. Large institutions or governments may not permit a joint venture because they are concerned about the transitory nature of the venture. They may require a single party to hold accountability for various reasons.

Architectural practices should clearly define – in writing – their share of the services and fees before entering into a joint venture. Some provincial and territorial associations regulate joint ventures and their names. For items to include in a joint venture agreement, see Appendix D – Checklist: Issues to Consider when Preparing a Joint Venture Agreement at the end of this chapter.

Multi-disciplinary Firms

Multi-disciplinary firms are professional companies which include architects and other professionals, usually engineers. Such firms may also include urban planners, landscape architects, interior designers, energy modelers, sustainable design, and other consultants. Multi-disciplinary firms must comply with the requirements of the provincial and territorial associations of architects in order to practice architecture. It can sometimes be beneficial to have all disciplines on a building project readily available in-house. Such an arrangement can simplify communication between and coordination of the various disciplines.

Foreign Firms

Certain foreign architectural firms have established branch offices in Canada. The structure of the foreign firm and its ownership must nevertheless comply with the requirements of the provincial and territorial associations of architects. Several Canadian firms have established branch offices overseas to better serve foreign clients.

Structure of an Architectural Practice

Once a firm is established, it requires an internal structure or mechanism for delivering architectural services. The structure of the practice depends on its leadership and its values and culture, and on the needs of the project.

There are several standard organizational structures:

- design teams or in-house studios (project-based organization);

- departments structured by responsibilities, such as design, document production, and contract administration (functional organization);

- a combination of the above, where the project architect negotiates with the departmental managers or office manager to acquire the needed resources for a specific project and works across the functional departments of the organization (matrix organization).

Some architectural practices subdivide the office into teams to deal with a project in its entirety; others compartmentalize the firm, permitting each department to specialize in one type or stage of architectural services. Each of these methods reflects a different approach to responsibilities and reporting relationships, and a different balance of efficiency and effectiveness.

Design Teams or In-house Studios – Project-based Organization

A design team is usually assembled for a specific project, drawing on the skills of personnel in the office. The team leader, typically a project architect, coordinates and manages the team and deals with the client, sometimes together with the “principal in charge.” Occasionally, some architectural practices establish studios which remain together as efficient working teams for an indefinite period of time.

Departments – Functional Organization

Some larger architectural practices subdivide staff into groups or departments. Usually each department is responsible for a different phase of the project, such as:

- business development and marketing;

- design and design development;

- construction documentation;

- construction administrations;

- specialized teams such as programming, sustainability and BIM;

- support teams such as accounting, human resources, information technology, management, etc.

However, regardless of departmentalization, there must always be an architect leading the project who is accountable for supervision and for directing the work related to the design of the project.

Other Professional Services

Several external professional services are likely to be required to support an architectural practice. These include but are not limited to:

- legal services;

- accounting and tax planning;

- insurance providers;

- investments and retirement planning;

- human resources;

- information technology.

Legal Services

Establishing a professional relationship with a lawyer is important for the architect. Legal services may be required for the following:

- establishing a partnership or corporation;

- preparing annual minutes for the corporation;

- entering a lease or purchasing office property;

- preparing certain employment agreements with staff;

- reviewing professional liability insurance options and claims;

- reviewing non-standard client-architect agreements or amendments to standard agreements;

- reviewing non-standard owner-contractor agreements or amendments to standard agreements (on behalf of the client);

- assisting in the collection of accounts which are in dispute;

- handling other disputes or legal issues (such as filing and processing liens and mortgages);

- human resources problems.

It may be necessary to establish a relationship with a number of different lawyers who have expertise in specific fields of practice, or, alternatively, with a larger firm of lawyers that has a range of in-house expertise.

Accounting and Tax Planning

It is also important to establish a relationship with an accountant. Accounting services may be required for the following:

- establishing a practice, whether a sole proprietorship, partnership or corporation;

- establishing financial terms of a partnership or shareholders’ agreement;

- preparing periodic balance sheets and profit/loss positions;

- preparing annual financial statements;

- preparing personal and corporate income tax returns;

- assisting in the preparation of sales and value-added tax returns;

- assisting a lawyer in the preparation of a corporation’s annual minutes;

- analyzing the financial position of the practice;

- providing tax planning advice.

Some larger architectural practices employ a controller, usually an accounting professional, who directs and monitors the day-to-day financial operations of the practice. It may still be required to engage an accountant to provide:

- tax planning advice;

- ongoing advice on the financial position of the firm;

- financial statements;

- if required, audited statements.

See also Chapter 3.4 – Financial Management for other issues to discuss with an accountant, and for an overview of the financial operations of an architectural practice.

Insurance Providers

An architectural practice will have a variety of insurance requirements. These will include:

Professional liability insurance:

- general coverage;

- special project coverage;

- add-on insurance or “excess” coverage.

In addition to the insurance related to the firm’s activities, the firm may need to hold policies related to:

Office premises and automobiles:

- theft and vandalism;

- accident;

- fire and other damage;

- owned and leased vehicles.

Life and accident insurance:

- personal;

- business partners and directors.

Disability insurance, to cover:

- office overhead;

- loss of business;

- personal income (income protection).

Medical and dental:

- extended medical care;

- dental plan;

- vision care.

Workers’ Compensation (regulated provincially).

To ensure that the practice is properly and adequately covered, consult an experienced insurance agent or an independent risk management advisor.

Several provincial and territorial associations of architects have established liaisons with certain insurance underwriters who provide discounted premiums to architects. Professional liability insurance is a specialized type of insurance provided by a limited number of insurance underwriters. In Ontario, Pro-Demnity Insurance Company, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Ontario Association of Architects, and in Quebec, the Fonds d’assurance de la responsabilité professionnelle de l’Ordre des architectes du Québec, provide professional liability insurance to their members.

See also Chapter 1.6 – The Organization of the Profession in Canada, Chart 5B: A Comparison of Provincial and Territorial Requirements Regarding Professional Liability Insurance.

Investment and Retirement Planning

Although not unique to the profession, all architects should plan for retirement and, therefore, seek the advice of a financial investment professional to ensure proper retirement planning.

See also Chapter 3.2 – Succession Planning for other considerations related to retirement planning.

References

Bens, Ingrid. Facilitating with Ease. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2018.

Clark, Tim, and Bruce Hazen. Business Models for Teams. New York: Portfolio Penguin, 2017.

Coxe, Weld, Nina F. Hartung, Hugh Hochberg, Brian J. Lewis, David H. Maister, Robert F. Mattox, and Peter A. Piven. Success Strategies for Design Professionals. The Coxe Group Inc., 1987.

Cramer, James P. Design Plus Enterprise: Seeking a new reality in architecture. Washington, D.C.: The American Institute of Architects Press, 1994.

Cuff, Dana. “Professions and Professional Life.” The Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice. Washington, D.C.: The American Institute of Architects Press, 1994.

Demkin, Joseph A., executive editor. The Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice. The American Institute of Architects. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2008.

Klein, Rena, FAIA. The Architect’s Guide to Small Firm Management: Making Chaos Work for Your Small Firm. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2010.

Kogan, Raymond F. Strategic Planning for Design Firms. Kaplan Publishing, 2007.

Maister, David H. Managing the Professional Service Firm. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1997.

McGill Business Consulting Group. Succeeding by Design - A Perspective on Strengthening the Profession of Architecture in Ontario and Canada. 2003.

Osterwalder, Alexander, and Yves Pigneur. Business Model Generation. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2010.

Osterwalder, Alexander, and Yves Pigneur. Value Proposition Design. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2014.

Stasiowski, Frank A. Strategic Planning: Preparing Your Firm for Success in the Future. Newton, MA: PSMJ Resources, Inc., 1997.

Verma, V.J. The Human Aspects of Project Management, Volume One: Organizing Projects for Success. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 1995.