Purpose of Drawings

Commonly known either as “working drawings” or “construction drawings,” the drawings forming part of the construction documentation package are a means of communicating, in standard formats, information in graphic language using lines, graphic symbols, CAD or building information modeling (BIM) representations and written annotations.

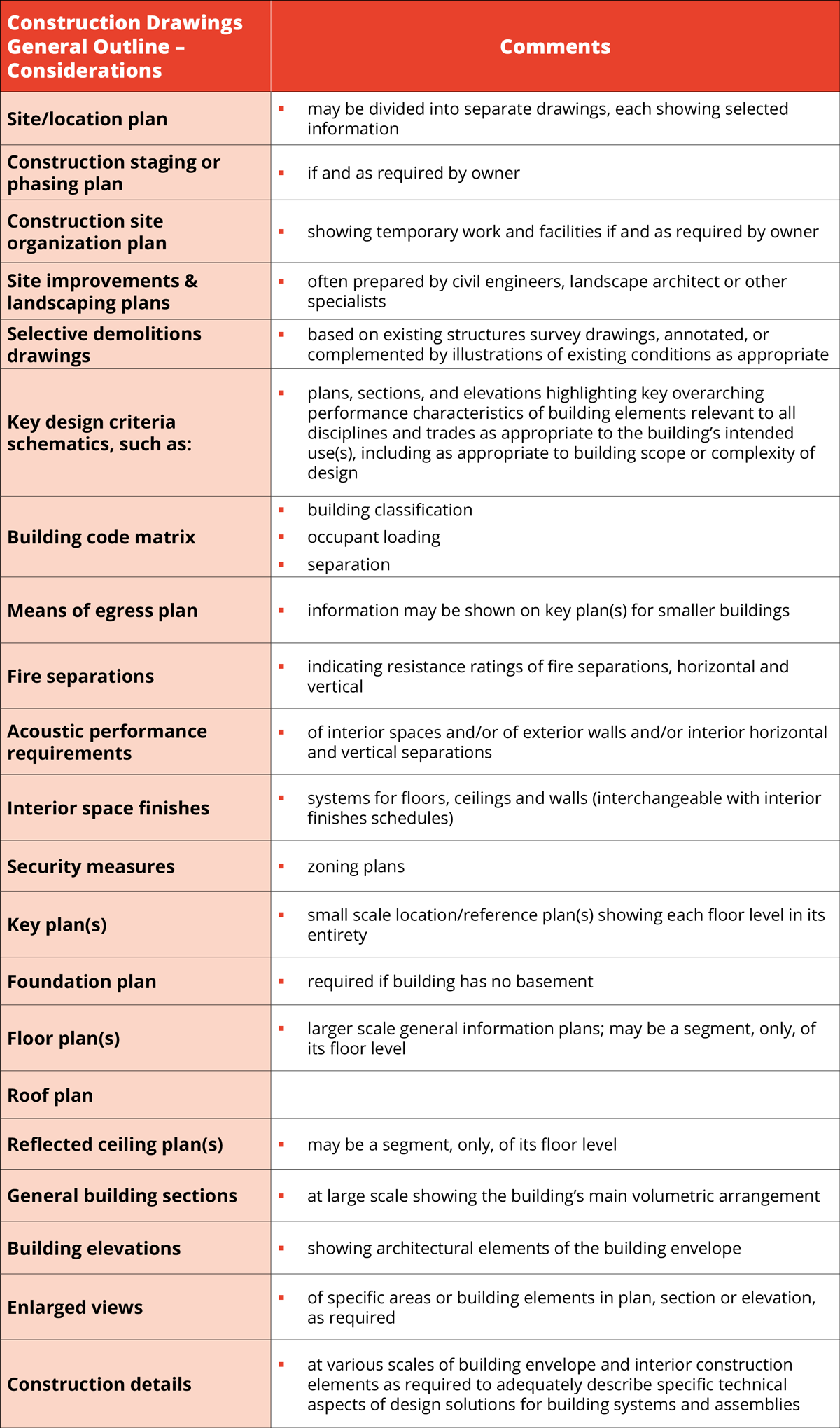

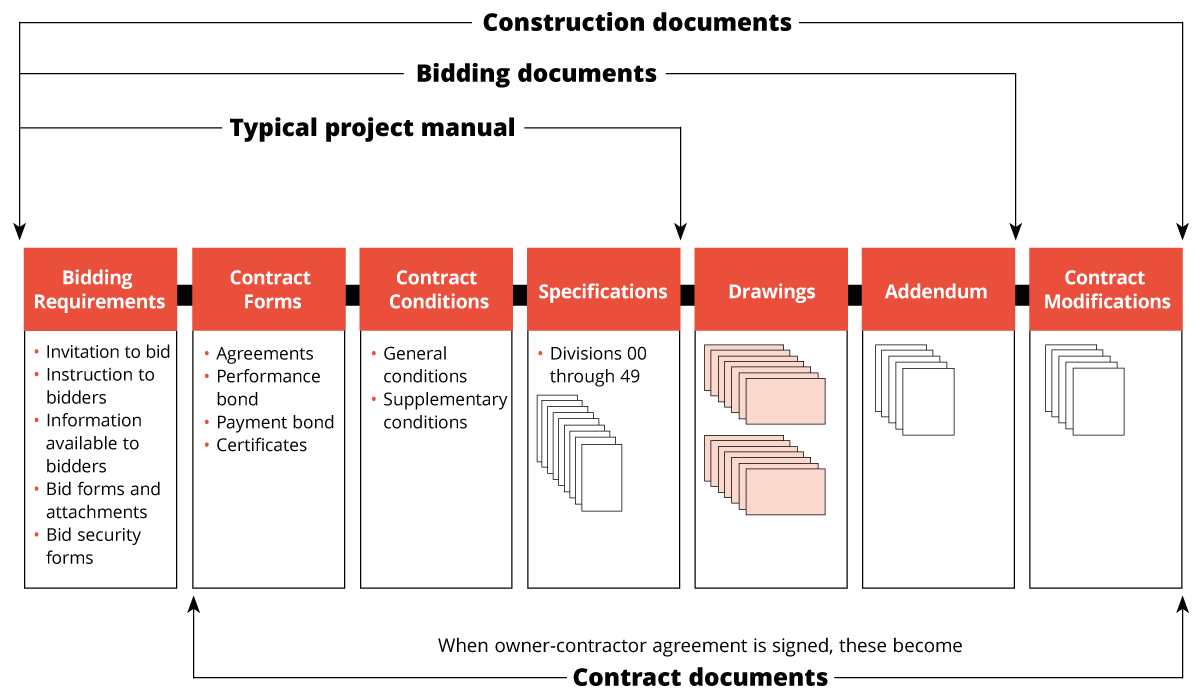

FIGURE 1 Format for Construction Documents

A fundamental change in the meaning of drawing has occurred following the widespread implementation of BIM. Since the emergence of architecture as a profession and the split between the master builder and the designer, drawings have been defined as a representation of the building. The drawing captured the design intent. The constructor was then expected to interpret the design intent as described using the language of drawing. The adoption of parametric modelling through BIM and the use of the same model by all the design consultants and the construction forces has resulted in a redefining of the drawing as a modality of communication. The “model” is less a representation of design intent and has become the building writ small or rather the building writ digital. This change has resulted in increased expectations of accuracy, resolution, and visualization for the design team.

The graphic information is traditionally represented in the form of orthographic projection views, such as floor plans, elevations and vertical sections, at various scales as appropriate to show the general arrangement of building elements and components, or to detail illustrations of specific features or elements. Perspective, axonometric and isometric views are also sometimes included to better illustrate complex arrangements, or assemblies, where appropriate, to better describe the design. Buildings are increasingly designed and documented as three-dimensional models, in part or in whole, using either CAD software or building information modeling (BIM) systems, and from which both orthographic and three-dimensional views can be extracted for inclusion in construction document sets.

In building renovation projects, and more particularly in heritage building rehabilitation and conservation projects, annotated photographs are also used as an efficient and convenient way to accurately represent the scope and nature of the work. These types of representations describe the relationships between building components (sometimes referred to as building assemblies or construction systems) and have the following characteristics:

- location of the building and exterior amenities in relation to fixed references;

- spatial location of elements in reference to fixed references and/or each other;

- name or identification of spaces, elements or assemblies for referral to other documents;

- size and dimension;

- shape and form;

- design intent and requirements or scope of work specifications;

- details or diagrams of connections for the building assembly.

Where design intents make it necessary, highly customized, unusual or innovative architectural details will be prominently featured in the drawings set as “prescriptive” graphic information. The large number of specific detail drawings and distinct views thereof will represent a high proportion of the time and effort invested in the construction documents development for architects. Where the achievement of such design intents is considered key to the project’s objective, they will also need early development and refinement so as to facilitate the timely resolution of design solutions for the related subordinate building elements in other disciplines.

Where the technical orientations defined at the schematic design stage project involve working with generic industry-standard conventional or specific proprietary component, assembly or system designs, it may be possible for construction documents to refer directly to the source documentation and not include graphic or written information readily available to users from standards organizations or manufacturers of proprietary components. Such features and characteristics, and all relevant information, may be extensively documented by their sources so as to be readily available to be inserted directly into drawings and/or specifications.

Construction drawings generally consolidate repetitive key information on separate sheets, references to which are inserted in other drawings, such as:

- schedules in tabular format providing specific information on various building elements or features such as:

- door/door frame/hardware, using door numbers indicated on plan views;

- interior floor/ceiling/wall finishes, using room names/numbers indicated on plan views;

- graphic representations of “typical” building components or assemblies, such as:

- exterior wall composition(s);

- roofing composition(s);

- interior partitions and walls composition(s);

- floor/ceiling assemblies including finishing materials and systems;

- door and door frame elevations and frame insertion details;

- interior glazed partitions’ compositions and elevations;

- indicating composition, materials, dimensional requirements and, as applicable, specific performance requirements, such as:

- thermal properties of building envelope elements;

- fire-resistance ratings of vertical or horizontal separations;

- acoustical properties of vertical or horizontal separations.

In larger and/or more complex projects, it may be more efficient for this type of information to be in a separate document formatted for this purpose, or directly within the specifications binder as, for example, appendices to the relevant specifications sections.

Many different individuals and organizations use drawings for a variety of purposes. The primary users are the architect and consultants, contractor and subcontractors, suppliers, and individual workers — the parties that are bound to one another to design or construct a building. Additional users may include:

- authorities having jurisdiction;

- financial institutions;

- tenants and end users of the building;

- facility managers and maintenance personnel;

- other construction industry professionals.

The construction drawings are used by:

- bidders:

- to prepare bids and to obtain bids from their subcontractors and suppliers;

- to form part of the project manual as binding contract information.

- constructors, general or trade contractors, systems/product manufacturers:

- to guide or direct them in materially performing the work;

- to inform them as required to facilitate their effective and efficient planning and organization of workflow sequences as well as quality control methods and procedures.

- authorities having jurisdiction, including public utilities authorities:

- to verify that the project conforms to existing regulations for the purpose of issuing permits;

- to plan and arrange for the provision of utilities and services.

- architects, collaborating engineers and other various specialized professionals:

- to exchange progress design information for the purposes of coordination and harmonization of designs and graphic representations across all disciplines;

- to obtain cost information on planned building elements and materials;

- to communicate project particulars to clients in order to obtain approval;

- to prepare cost estimates;

- as a control instrument to review the work on site and to determine general conformity of construction work performed with design intents as expressed in the construction contract documents.

- clients:

- to verify and confirm conformity to approved schematic design and to the project’s specified requirements;

- to form part of the tender documentation package;

- to form part of the documents of the construction contract to be executed with the contractor.

It is important for architects to also bear in mind the distinction that some make between the scope and level of details required respectively for the purposes of contractors establishing bids and for performing actual construction work. Theoretically, the two contexts may have distinct requirements for what content is critical, in accordance with differing forms of contracting and procurement. However, the reliance on agreements based upon one form of procurement must be used with caution and clarity – if the form of procurement changes from, say, a single known and selected bidder to an open public tender, it may be that additional construction documentation is required. The architect’s client-architect agreement should recognize this sort of possibility by making provision for additional, paid services where the agreed procurement mode changes.

Construction contracts normally include provisions allowing information supplements, usually called site instructions or supplemental instructions, to be added to either tender documents or contract documents. These may be prepared and issued during construction work and may include additional drawings or specifications, in the belief that this additional information does not impact either contract price or time. Additional drawings may also be needed to clarify information already provided in the construction documents. Once distributed, these supplemental instructions and drawings generally form an integral part of the set of construction contract documents, as if they had been part of bid documents.

Construction Drawings Set General Outline

Depending on scope/complexity of project, architectural drawings may include:

CAD Standards

CAD (computer-aided drawing) and building information modeling (BIM) have replaced manual drafting as the primary method for producing construction drawings. Production techniques may vary within the same office, depending on the human and physical resources available and the nature of the project. Some clients require that drawings be prepared using certain standards.

Standards define the size and style of fonts, dimensions, lines, and hatching or other ways to represent materials. They also suggest various ways to create borders and title blocks, standard details, symbols, etc.

It is especially important to establish a standard system for naming and giving attributes to layers to facilitate the development of construction drawings and make them user-friendly for consultants and others. Some clients will require electronic files of the construction drawings (or record drawings) for the future management of their building. Therefore, architects must often use the client’s layering system or other drawing standards.

Some institutions, such as Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) and large health and educational institutions, have created their own drawing standards. It is important to obtain these standards at the start of the project.

It is important, at the start of the project, to establish protocols for the creation and transfer of electronic information.

The Uniform Drawing System (UDS) is a guideline which includes the following modules:

- Drawing Set Organization (numbering system and sequence for drawings, etc.);

- Sheet Organization (system for numbering drawings, details and organizing sheets);

- Schedules (format, heading terminology, and organization);

- Drafting Conventions;

- Symbols;

- Terms and Abbreviations;

- Layers (see note re UDS below);

- Notations.

The UDS has adopted the American Institute of Architect (AIA) CAD Layer Guidelines, which were originally developed and published by the AIA.

Organization of Drawings

To produce working drawings, one must first create a list of information required, including a preliminary list of drawings. Drawings and documents prepared during the design development phase may be used to determine which construction details must be drawn.

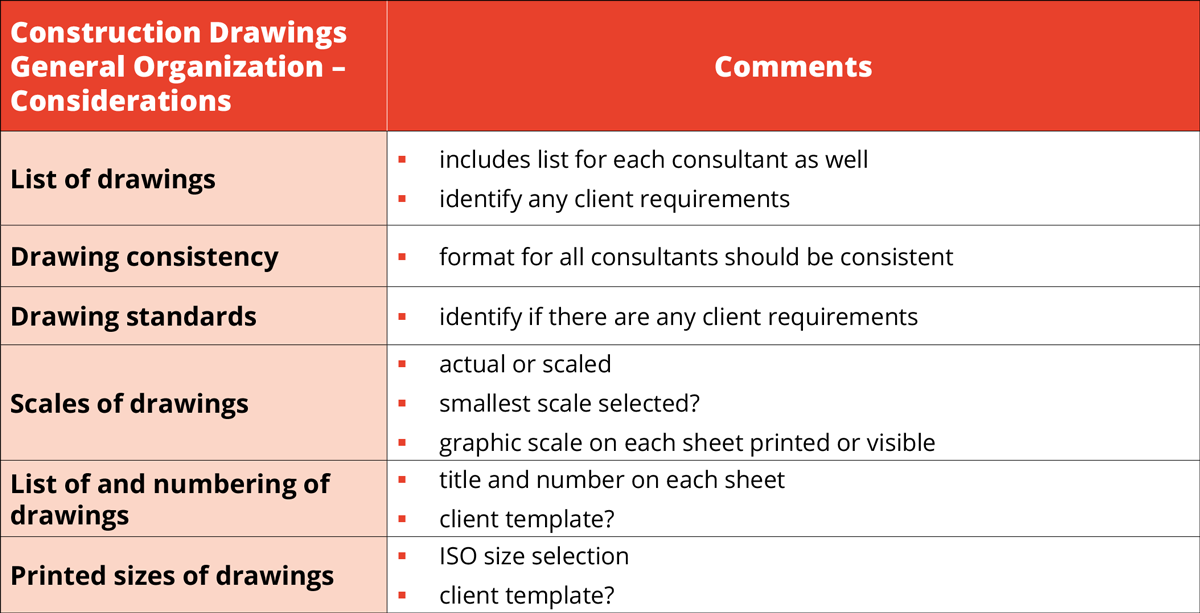

This list also enables the project architect to ascertain which elements require additional research or information from the client or consultants. The format of all drawings, including those of the engineers and consultants, should be consistent.

The graphic construction section discusses the graphic and presentation standards as they apply to printed documents. These standards are usually embedded as default parameters and setups within the configuration of the digital drafting tools. Default setup parameters can be developed by architects as either ad-hoc in-house or proprietary corporate configurations.

These rules and standards may also be governed by mandatory formatting practice imposed by client organizations, as is common with some corporate real estate organizations, public institutions such as universities or hospitals, governmental and para-governmental agencies or Crown corporations. The applicable standards may be developed by the client organization or defined by recognized standards organizations. Such standards include the following elements.

Scales

In the past, it was necessary to determine and decide on a scale for each construction drawing.

Some current digital drawing and drafting tools work from actual dimensions, and scales become an issue only with respect to plotting drawings on paper. Other tools do work from scales defined on the digital drawings. For legibility, the scale at which drawings will be plotted must be determined in accordance with sheet formats selected as well as with graphic contents. The smallest scale in which information can be clearly presented is chosen. Hard copies that are reduced for distribution must still be legible. Along with the scale(s) used for all drawings, a graphic scale should be indicated on these documents, although such indications are intended for convenience only because dimensions obtained from scale measurements taken from drawings are typically specified as non-binding for contractual purposes.

List of Drawings, Numbering and Sizes

Each sheet of the construction drawings must have a title and a number. The Uniform Drawing System provides guidelines for a standard, yet flexible, system of title blocks and sheet numbers.

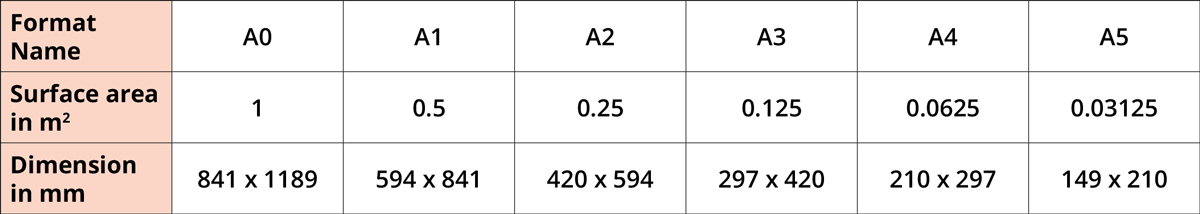

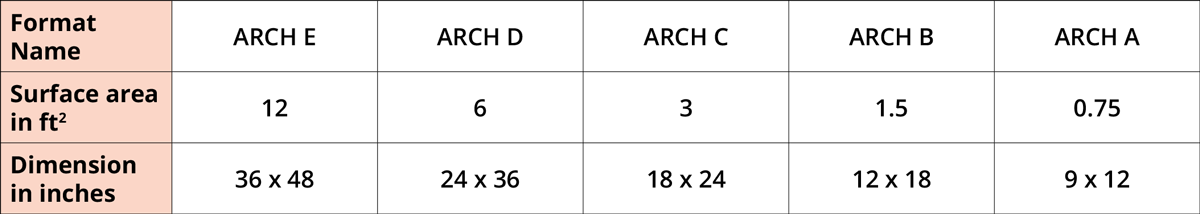

The range of ISO formats may be used for the sizes of printed drawing sheets (see Table 1). This range offers the following features that are useful when drawings must be reproduced on a larger or smaller scale:

- the surface area of each format is twice that of the preceding format;

- any two consecutive formats have the same height-to-width ratio (that is, the same proportions).

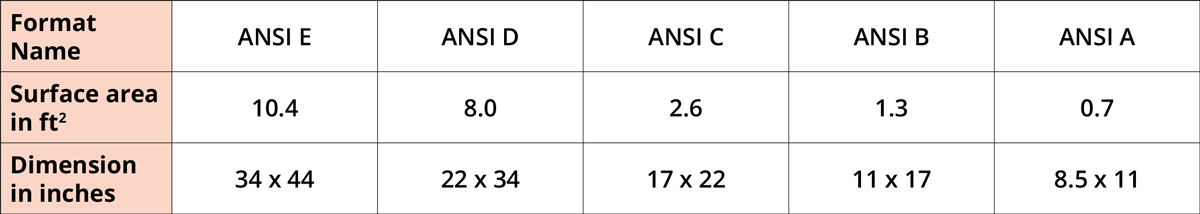

TABLE 3 Sizes of Construction Drawings – ANSI Format

For further information on drawing sheet formats and sizes, see:

- for North American standards: https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/North_American_Paper_Sizes;

- for ISO standards: https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/Paper_Sizes.

Clients may sometimes have their own templates for drawing sheet layouts and title block for various sheet sizes, and many architectural practices have developed their own specific preferences and designs.

Title Block

The title block may contain the following information:

- project name and address/location;

- project number;

- date, including date of first issue and dates of all revisions;

- purpose for issuing the drawing;

- drawing title;

- drawing number;

- scale;

- details indicating revisions (such as revision number, date, general description, initials of the originator);

- name and contact information (in many provinces, the name of the holder of the Certificate of Practice must appear);

- name or initials of the draftsperson and the individual checking the drawing;

- a location for applying the professional seal and signature (refer to the regulations of the provincial associations of architects for regulations on applying the professional seal. See also Appendix E, Chart F: Comparison of Provincial or Territorial Requirements/Guidelines Regarding the Application of Seals in Chapter 1.6 – The Organization of the Profession in Canada).

Usually, the drawing (either in the title block or elsewhere) includes the following information:

- north arrow on plan views;

- key plan, indicating the relationship of partial plans to the overall plan, orientation, etc.;

- the electronic file name;

- dates and notations indicating the purpose for issuing the drawing (such as “Issued for Bid” and “Not for Construction”);

- notice of copyright.

See Appendix A of this chapter for more information on copyright.

See also Section 5.2 – “Drawing Notations” in Chapter 6.8 – Standard Forms for the Management of the Project.

Depending on the type of project and the contractual arrangement with the consultants, as well as the requirements of the professional liability insurer, the title block includes the name, address, telephone number, e-mail address and fax numbers of engineers or other consultants. Also, the architect must take care to conform to the requirements of the provincial or territorial association.

Notes, Symbols and Dimensions

Notes, symbols, abbreviations, dimensions and references to other drawings should be expressed in the same way on all the drawings, using recognized conventions.

Notes on the drawings should be kept to the minimum necessary to understand the architect’s intentions. (References to standards and instructions about the execution of the work should be included in the specifications, not on the drawings.) Standard symbols should be used to show structural grids on the plans, as well as references to elevations, sections, details and enlarged plans. References to sectional views, windows and details are usually indicated on the elevations. References to details are usually indicated on the cross sections and wall sections. As a general principle, notes and dimensions should be placed in the most significant location in the documents and not repeated elsewhere, in order to minimize opportunities for discrepancies or contradictions appearing where information is redundant as provided on other drawings or in written specifications.

If a material is identified on the drawings by a generally accepted symbol, a defined symbol or a generic name, no further descriptive notes are necessary. Too many notes obscure the drawings, increase search time to find information, and promote inconsistency and duplication. Repetitive items such as doors, windows and interior finishes should only provide a reference to identify the material or components.

Drawings identify a material or product only by a generic name, and illustrate its approximate shape, dimensions and location.

Plans indicate the length and width of buildings as well as the width and thickness of walls, whereas elevations and vertical sections indicate height. Drawings should include all the plans, elevations, sections and project-specific design details necessary to fully document the requirements of the work to be executed.

Dimensions are part of the information about building elements or systems examined in the course of the development of detailed design solutions. In the final issue of the construction documents, only the information sufficient and necessary to instruct contractors to properly position elements relative to each other and/or geodesic reference points should appear in order to avoid possible confusion or conflicting data in the drawing set, especially between large-scale and small-scale drawings.

The method of dimensioning should correspond to the sequence of construction, starting from site survey reference points and lines. All dimensions should preferably be indicated about a single reference point or line established by logical sequence of those that get “built in” first. Where the critical criteria for the positioning of elements relative to each other are not a fixed, linear value but rather conditioned by actual as-built dimensions, such as, for example, even spacing or centering, this is the information that must be conveyed by dimension lines rather than exact numerical values that are not in themselves critical to materializing design intents.

If the total of a set of dimensions must add up to a given dimension, it may be necessary to give an approximate value for one dimension or even to omit one of the less critical dimensions.

See the “Checklist: Internal Review of Drawings” in Appendices F to I at the end of this chapter for a detailed list of information that is recommended to be included on all plans and drawings.

Coordination of Drawings

The project architect needs to be fully aware of the progress of the drawings. Therefore, at intervals appropriate to the project’s complexity, the project architect may:

- arrange internal and external coordination meetings;

- review and revise drawings as they are being developed.

It is particularly important to plan regular meetings and to exchange information with project engineers on an ongoing basis. The project architect usually notes and documents the following:

- decisions;

- suggested changes;

- new requirements from the design team.

Coordination of the drawings with specifications is also necessary. In particular, the drawings and the specifications must use the same terminology for the same elements to avoid ambiguity and, therefore, reduce the risk of disputes during the execution of the work.

Client-supplied equipment must also be coordinated. Client changes to the program or modifications to the layout can have far-reaching consequences at this stage and the architect should be remunerated accordingly. If the architect is engaged to manage and coordinate the consultants, then the project architect will arrange for each confirmed change to be:

- communicated to the various engineers and consultants;

- integrated into the working drawings and other construction documents.

Checklists

Checklists outlining the scope and methodologies for planning, producing and coordinating a complete set of construction documents are powerful tools.

Depending on the scale and complexity of the project, the architect may carry out the following review procedures:

- conduct interim and final reviews before completing the construction drawings, addressing both form and substance qualitative issues;

- in accordance with final design development sequence planning, conduct interim and final reviews for technical feasibility in site and/or physical constructability of details, assemblies and related site operations and construction methods. May require the collaboration of civil, structural, and mechanical engineers or other specialists involved in the project;

- ensure that the client reviews the drawings and specifications;

- ask a senior architect in the practice who is not associated with the project to check the drawings and specifications for:

- consistency with client-approved design development stage documents;

- errors and omissions;

- compliance with graphic standards and for cross-referencing accuracy and completeness;

- require different individuals to conduct partial reviews (for example, dimensions, details, notes and related specification sections);

- check all dimensions twice;

- where specifications are prepared by a specialist solely assigned to this task, ensure that the specification writer conducts a final review of the construction drawings.

Revisions to the Drawings

In practice, changes to certain design elements may be necessary as the construction details are reviewed, developed and coordinated with the details and specifications of engineers and other consultants.

To ensure proper coordination, the project architect may:

- obtain information from the client about special technical needs related to the project (for example, medical equipment);

- inform the client about significant changes (and submit alternative solutions, if possible and appropriate);

- make the client aware of the importance of making decisions and giving approvals quickly.

The engineers and other consultants should also be advised of any modifications or design changes.

To identify revisions, changes to specific drawings or parts of larger drawings should be graphically highlighted and the title block of each revision of the drawings should indicate the date, the reason for the revision, and the nature of the changes. During the preparation of drawings, sheets issued for coordination should have successive revisions from successive issues clearly visible and recognizable as such (in a manner like the redline method used for text) in order to facilitate the process. A copy of the final version of each drawing showing the full history of progress revisions in the title block should be conserved for reference purposes. The history of progress revisions should not be visible to anyone other than the client and collaborating consultants, and should be removed entirely from drawings issued as bid documents.

Drawings issued for construction should only show the history of revisions made by addenda during the tender stage and after construction contract award.

Engineering Drawings

Structural Drawings

During the preliminary design phases of the project, the architect and the structural engineer should have already determined the structural framing system. During the construction documents phase, the structural engineer prepares:

- detailed calculations of all structural elements;

- plans and details;

- structural sections of the specifications (usually Divisions 03, 05, and 06);

- a final construction cost estimate of the structural components.

Mechanical and Electrical Drawings

Depending on the nature of the project, mechanical drawings are for the trades of heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC), plumbing and drainage, and specialty trades (such as sprinklers and gas piping).

The mechanical engineer usually prepares a separate set of drawings for each trade.

During the construction documents phase, the mechanical and electrical engineers should prepare:

- detailed calculations;

- plans, details and schematic diagrams;

- mechanical and electrical sections of the specifications (Divisions 21 to 29 inclusive);

- a final construction cost estimate of the mechanical and electrical components.

Coordination of Engineering Drawings

If the architect is retained to manage and coordinate the project team, one of the architect’s most important tasks during the production of the drawings is the coordination of the engineering drawings (and drawings from other specialists). Coordination is not to be confused with designing and documenting the technical content contained in the engineering drawings, which is the responsibility of each respective engineer. The architect will check that all relevant information is on the appropriate drawing and that the design of one discipline includes the necessary work to accommodate the work designed by another engineer. For example, problems due to the interference of conflicting elements such as ductwork, light fixtures, piping and the structural framing system must be resolved.

Sharing all necessary information with the engineering consultants as soon as it is available helps to minimize coordination problems.

Regular coordination meetings or “interdisciplinary coordination reviews” are also essential for ongoing information exchange and to collectively solve any coordination issues. The earlier these meetings are held during the production of the drawings, the easier it is for each professional to integrate ideas and revisions from other members of the consulting team.

Any design changes, and the reason for the design changes, should be immediately distributed to all engineers. Using a planned design development sequence checklist can be helpful in highlighting what elements for which coordination are of critical importance and at what stage in the progress of drawings for each discipline concerned.

Should the case arise that substantial changes to the design in one of the engineering disciplines become necessary to adapt to architectural designs or designs from other disciplines that are more critically important to the project, as the coordinating professional, the architect must intervene to direct what revisions must be made in which discipline to which design elements. When upon coordination, the architect considers requesting revisions or substantive changes to an engineer’s or other specialist consultant’s design, due consideration should be given, in consultation with the involved professionals, to the following:

- incidence on other consultants’ work;

- impact on the client’s previously issued approvals of designs in all disciplines;

- impact, if any, on the integrity of the client-approved and expected results regarding the architectural concept and design;

- impact, if any, on the construction documents stage schedule and/or costs of services to the client;

- potential impact on project objectives such as anticipated or planned construction costs and/or schedules as well as expected or required construction quality and construction trades market feasibility;

- range and depth to which design alternatives should be examined by the professionals concerned in collaboration with the architect as appropriate.

The importance of conscientiously timely and effective interdisciplinary coordination throughout the construction documents stage cannot be overstated. Although the sensitivity during the construction stage to effective coordination does vary considerably depending on projects’ variations, such as nature and scope, the inherent level of technical or programmatic complexity, and the conditions set by project delivery methods and/or construction contract modalities, it remains that all project participants can only benefit from coordination processes that minimize or suppress the opportunities for changes to the work arising from coordination lapses. This is especially important as remedying them during the construction stage can be considerably more costly in time and effort, and can create significantly increased contract costs and/or schedule, and thus, exposure liability claims.