Definitions

Certificate: A document attesting to the truth of a fact; in construction. A certificate is prepared by a professional, either an architect or an engineer.

Certificate of Substantial Performance: A certificate issued under the appropriate lien legislation attesting that the contract between the owner and the contractor is substantially complete.

Guaranty: A three-party agreement in which the third party (such as a surety) guarantees the performance of an obligation to the second party (such as an owner) in the event of default of the first party (such as a contractor)( CCDC).

Holdback: A percentage of the monetary amount payable under a (construction) contract, which is held as security for a certain period. The percentage and period are based on the provincial lien legislation.

Lien: A legal claim on real property to satisfy a debt owed to the lien claimant by the property owner. This claim can carry the right to sell the property upon default.

Maintenance: The act of keeping a building system, process or property in proper and efficient working condition.

Post-occupancy Evaluation: An assessment of the performance of a building after the building has been occupied. The evaluation may address one or more different aspects of building performance.

Ready-for-Takeover: A term adopted by the Canadian Construction Document Committee (CCDC), used to describe a set of contractual and regulatory requirements that must be satisfied prior to achieving a financial milestone for the release of the project close-out payment(s).

Warranty: A two-party agreement which provides an assurance by a builder or a seller of goods (such as a contractor) to a purchaser (such as an owner) that the warrantor will assume stipulated responsibilities for correction of defects in the goods within a stated period of time (CCDC).

Preamble

This chapter discusses the close-out procedures for construction projects. Administrative, contractual, and regulatory close-out procedures vary across Canada based on the provincial or territorial jurisdiction. For example, some provinces do not define or use the term “substantial performance” to trigger a financial milestone association with release of the statutory holdback. As another example, the Province of Quebec does not apply a statutory holdback to contractor payments. The architect must be familiar with the lien and payment legislation in all jurisdictions in which they practise.

Introduction

As the construction of a project nears completion or after the building is complete, the architect continues to provide professional services to the client. In a project, even though the architect may have provided great design and contract administration services, poor takeover and commissioning services may be all a client remembers about the project, leaving the architect with an overall poor review.

Most owners consider this phase just as important as the design and construction documents. Incomplete project close-out can leave items not addressed to resurface later, causing problems and risk of litigation.

Some of these services include:

- takeover procedures;

- commissioning;

- post-occupancy evaluation.

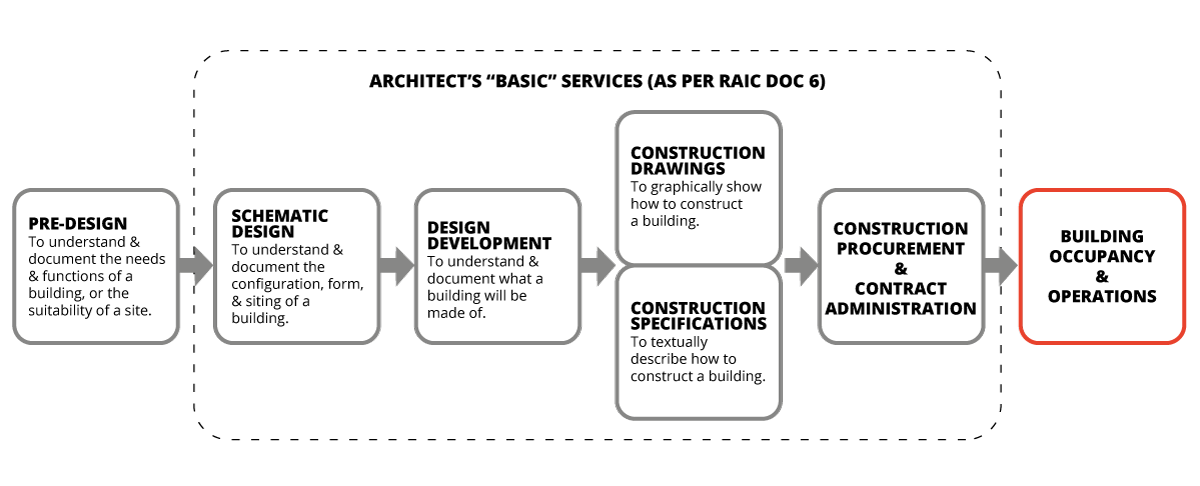

Takeover procedures are a normal part of the architect’s basic services that close the contract administration phase. The takeover deliverables should be clearly specified in the general requirements section of specifications listing the owner’s requirements for record documents, demonstration and training, and operations and maintenance documentation.

After takeover, the architect is responsible for reviewing defects and deficiencies during the warranty period and for notifying the contractor of items to be corrected. Most client-architect agreements terminate after the one-year warranty period. Therefore, work extending beyond this period is an additional service.

Commissioning is a systematic process of ensuring that new building systems perform according to the documented design intent and the owner’s operational needs, and that specified system documentation and training are provided to the facility staff.

Commissioning is a term that is often misused to refer to those activities that occur when a project is taken over by the client. In fact, commissioning is a separate and distinct service, which may commence at the beginning of a project and may continue until occupancy by the owner. Takeover, by contrast, starts when a project nears construction completion. Commissioning is an additional service often provided by an independent third party, a commissioning agent. This process may require the participation of a commissioning agent to manage and verify the performance of all the components of the building’s operation, sequence of operations, testing and balancing of mechanical and electrical systems.

Post-occupancy evaluation is not normally a part of the architect’s traditional basic services but can be provided as an additional service. The purpose is to investigate and assess the performance of completed buildings. It may be conducted at six- or 12-month intervals. The evaluation may examine the technical performance of a system or an assembly such as the building envelope, or functional performance such as the efficiency of the layout of the building’s interior.

Following occupancy, the architect often:

- reviews the effectiveness of the architectural practice’s in-house procedures, i.e., lessons learned;

- records information about the project for future reference, i.e., standard detail;

- conducts client/owner/tenant satisfaction survey(s) on the built solution and notes possible improvements;

- prepares presentation material for incorporation into the practice’s promotional material.

With the increasing integration of green building rating systems into projects, post-occupancy evaluation may be a requirement of certifications systems.

Takeover Procedures

Takeover procedures are required for the orderly takeover and transition of the building project by the owner. They are also necessary to protect the interests of the owner, contractor, and architect. Architects should be thoroughly familiar with the lien legislation in the province or territory where the project is located.

See Appendix A – Provincial and Territorial Lien Legislation for links to lien legislation in each province and territory.

Ready for Takeover and Substantial Performance

Not all provincial or territorial jurisdictions apply lien legislation in the same way, and not all regulations employ “substantial performance” as a key financial milestone to release the lien holdback. Substantial performance is a regulatory rather than contractual requirement of the contractor. To provide consistency in contractual documents across the country, the CCDC has adopted the term “ready-for-takeover” in its standard contract forms to describe a list of factors that, once satisfied, result in project completion. One of the factors leading to “ready-for-takeover” is “substantial performance.”

Ready-for-takeover may vary from contract to contract; however, CCDC has established a list of factors that constitute the ready-for-takeover state. From CCDC 2 2020:

12.1.1 The prerequisites to attaining Ready-for-Takeover of the Work are limited to the following:

.1 The Consultant has certified or verified the Substantial Performance of the Work.

.2 Evidence of compliance with the requirements for occupancy or occupancy permit as prescribed by the authorities having jurisdiction.

.3 Final cleaning and waste removal at the time of applying for Ready-for-Takeover, as required by the Contract Documents.

.4 The delivery to the Owner of such operations and maintenance documents reasonably necessary for immediate operation and maintenance, as required by the Contract Documents.

.5 Make available a copy of the as-built drawings completed to date on site.

.6 Startup, testing required for immediate occupancy, as required by the Contract Documents.

.7 Ability to secure access to the Work has been provided to the Owner, if required by the Contract Documents.

.8 Demonstration and training, as required by the Contract Documents, is scheduled by the Contractor acting reasonably.

Leading up to this point, through regular site visits, the architect and/or their staff should validate that the work has been completed in general conformance with the contract documents.

Project construction specifications and/or the CCDC will stipulate the contractor’s deliverables at substantial performance that normally include a comprehensive list of items not yet completed and an application for review by the consultant in writing.

Under the terms and conditions of CCDC 2 – Stipulated Price Contract, and if permitted by the lien legislation of the place of the work, the contractor may apply for early release of the holdback related to a subcontractor’s or supplier’s work which was performed earlier (such as structural steel fabrication and erection). The architect should review the definition of substantial performance in the appropriate lien legislation.

The Ontario Association of Architects has prepared detailed practice bulletins providing advice on the release of holdback monies for subcontracts which are certified as complete, such as those for excavation and foundation subcontracts, to allow for the early or progressive release of holdback.

Generally, for projects that involve new buildings or renovation of unoccupied space, a project is deemed substantially complete when both the following criteria are met:

- The building is ready for its intended use and, if applicable, an occupancy permit is issued.

- The balance of payment to the contractor is at a level below the threshold indicating that the work has been substantially performed as stated in provincial and territorial construction lien legislation.

Architects are usually free to create their own template for issuing a certificate indicating that work has been substantially performed but note that some jurisdictions require the certificate to be on a form prescribed by legislation. The contractor may also be required to arrange for the certificate to be published in a construction trade newspaper as a condition of the release of a statutory holdback. The architect should request proof of the publication date. The publication serves as formal notification to all subcontractors and suppliers who have the right to place a lien on the project that the period for making a lien claim will expire within a certain number of days, as defined in the provincial or territorial lien legislation, from the date of publication.

The warranty period for the project commences on the date indicated in the contract documents. In the case of the CCDC 2 stipulated price contract, the warranty period starts at “ready-for-takeover.”

For the purposes of release of a statutory holdback, it is possible to waive the requirements associated with the certificate of substantial performance and to proceed directly to a statement of deemed total completion (as defined in the lien legislation). In this case, the warranty period commences on the date of total completion. This is often used on small projects when the time between substantial performance and total completion is short. When total completion is exercised, publishing in a construction trade newspaper by the contractor becomes optional. Architects should ensure that the wording in the specification allows for deemed total completion or that a substantial performance date is established even if the contractor does not request that it be certified.

Final Certificate for Payment

Once the architect is satisfied that all deficiencies have been corrected and that all work under the contract has been completed, the contractor can apply for payment for the outstanding amount. The final completion or correction of deficiencies can be frustrating for the architect for the following reasons:

- progress towards final completion of outstanding deficiencies seems to be very slow;

- the architect’s authority to certify payments and thus influence the contractor to work expeditiously decreases once the major part of the payment has been released;

- many contractors tend to lose interest in the project when there is no longer a significant financial incentive for its completion, particularly when the outstanding work is the responsibility of subcontractors.

The architect then prepares and issues the final certificate for payment. The date on this certificate will usually be the date of deemed completion of the contract, but, in some circumstances, the deemed date of completion may be an earlier date. In either case, the certificate should specifically confirm the deemed date of completion as stated in the statement of completion.

The definition of completed, in some provincial or territorial lien acts, permits a small dollar value to remain outstanding. This outstanding amount is the cost of:

- actual total completion;

- correction of known defects;

- last supply of outstanding services or materials.

The architect also prepares a certificate for the release of remaining statutory holdback monies payable, based on the number of days defined in the lien legislation after the date on which the contract is deemed to be complete.

If the contractor is efficient in correcting all the deficiencies, the date of this certificate may precede the date for release of final holdback.

Certification for Release of Holdback

The architect prepares a certificate authorizing payment of the amount of holdback which has accrued to the date of substantial performance. The certificate should be dated for payment one day after the termination of the lien claim period. When issuing the release of the holdback certificate, the architect should advise the owner to obtain legal counsel to ensure that no liens have been registered or notices of liens have been received. Typically, the owner will instruct their lawyer to undertake this determination. The architect should not perform this legal service; however, the architect should notify the owner that, if no liens exist, the holdback is payable on the date of the certificate.

The terms of CCDC 2 require the owner to place the holdback amount in a bank account (if a separate holdback account has not already been established) in the joint names of the owner and the contractor, ten days before the expiry of the holdback period. In some provinces the lien legislation requires that the holdback monies be paid into a holdback trust account with every progress payment to the contractor.

Application for release of holdback and certification for release of holdback relate to the release of monies which were previously invoiced for and certified as due and payable on a month-by-month basis. The holdback monies are a trust fund. This fund cannot be used to enforce the performance of the contractor nor to ensure that deficiencies are corrected. Certification of payment for known deficiencies should never be made until the performance of the work is acceptable.

Letters of Assurance

In some jurisdictions, authorities having jurisdiction require a letter of assurance, letter of undertaking or commitment certificate from the architect or registered professional that a building has been constructed in general compliance with the building code, applicable regulations, and the construction documents accepted for building permit purposes. The letter of assurance may be required before an occupancy permit is issued. Letters from subconsultants may also be required; engineers sometimes refer to these as letters of general compliance.

Final Submissions

Prior to occupancy of the building by the owner, the contractor must satisfy the conditions of ready-for-takeover and forward required documentation to the architect for review. This may include:

- operations instructions and maintenance manuals;

- a complete set of keys;

- record documents, which may include shop drawings in the appropriate format as specified in the contract documents;

- maintenance materials and spare parts;

- copies of warranties and bonds for each system along with dates for warranty periods;

- certification of the operation of various systems, such as:

- fire alarm;

- sprinkler system;

- HVAC systems;

- security system;

- boiler plant.

It is important for the architect and the engineers to scrutinize these items carefully because they may be inaccurate or incomplete on first submission and require re-submission before they are acceptable. If the submission process is left to the last minute, the unacceptability of the documentation can delay the completion of training sessions and performance testing. It is good policy to notify the contractor of the amount of the contract that cannot be certified until submissions are satisfactory.

The final submission may be in two stages:

Stage 1: Those items required for the proper operation of the premises for occupancy and, therefore, for certification of substantial performance;

Stage 2: Those items necessary to complete the contract.

In addition to final submissions, it is typical to arrange for a demonstration of all building systems and training of the owners for those systems with the following present:

- the owner or owner’s designated representative(s) or staff;

- the owner’s maintenance personnel;

- the design professionals;

- the subcontractors or trades responsible for the systems;

- the authorities having jurisdiction (for certain systems only, such as testing of fire alarm systems).

Instruction may include the following:

- review of documentation;

- operations;

- adjustments;

- troubleshooting;

- maintenance;

- repairs.

The requirements of final cleaning are normally specified in the contract documents and are also a requirement of project close-out. Final cleaning specifications would also address the proper and environmentally safe use and disposal of waste and other hazardous materials.

Ultimately, all actions and submission of ready-for-takeover must be satisfied by the contractor.

It is also at this point of a project when the architect benefits from assembling a file for their own future reference, which provides a summary of the project, costs for construction and professional services, time spent, and other information that could be used for reference on future projects and/or for improving office standard practices.

Occupancy

Building occupancy typically occurs because of one of three situations:

Unconditional Occupancy

Unconditional occupancy occurs when the scope of work associated with a building permit and especially the life and safety portion of the building code are compliant, complete, and accepted. The authority having jurisdiction formally issues an occupancy permit, or occupancy certificate, or simply a notice of final inspection.

Conditional Occupancy

Conditional occupancy occurs when a building, or portion thereof, may be considered safe but a portion of the project is incomplete with respect to the construction documents submitted for the building permit, or with respect to the permit conditions or substantial building code compliance.

Phased (or Partial) Occupancy

Phased (or partial) occupancy occurs when a discrete, or stand-alone, portion of a building is complete with respect to the scope of work shown (for that portion) on the construction documents submitted for the building permit, or with respect to the permit conditions or substantial building code compliance. This is common for large condominiums where lower floors may be occupied while construction continues on the upper floors.

In all situations noted above, the final issuance of an occupancy permit (or local equivalent) or the authorization of a conditional or phased (or partial) occupancy is the role of the authority having jurisdiction. It is advisable to check with the provincial or territorial association of architects for advice on documentation to support conditional and phased occupancy. At the final step, the architect should always strive to achieve unconditional (full) occupancy to close out the project.

Additional services for fees are justified for phased occupancies and should be clearly stated in the owner-architect agreement.

Commissioning

Commissioning includes a range of activities undertaken to transform the design of a facility into a fully integrated and operating system. It is a process of quality assurance which:

- begins with the definition of the “design intent” and ends with the delivery of a building;

- confirms the contractor’s implementation of the architect’s design as defined in the contract documents;

- confirms the ability of the architect’s design to satisfy the client’s defined requirements;

- addresses any shortcomings.

A useful reference for the commissioning is Natural Resources Canada’s Commissioning of New Buildings website, https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/buildings/commissioning-new-buildings/20679.

For large and complex projects, the owner may engage a commissioning agent as an independent third party to verify that both the facility design and the resulting construction satisfy the client’s objectives and requirements. In addition, the commissioning agent verifies the contractor’s performance of the contract. Early involvement of a commissioning agent as a project team member can assist in clear communication of the design intent to both the architect and the contractor.

The commissioning agent can:

- provide useful and objective input to the problem-solving process;

- oversee and verify results by conducting tests.

Commissioning and the services of a commissioning agent are over and above the architect’s normal fee. Architects are advised to review conflict of interest regulations in their jurisdiction when considering providing commissioning services.

The data obtained from commissioning can also be used as a baseline for future evaluations of the building’s systems and performance.

Pre-occupancy Services

Commissioning may begin at the pre-design stage of a project with an interpretation of the client’s expectations in the functional program. See Chapter 6.1 – Pre-design for information on functional programs.

With the creation of a program of requirements, the client’s expectations are documented, working from the general to the specific, to develop a logic diagram. The design intent identifies paths of activity necessary to accomplish stated goals. The logic diagram and the functional program should be reviewed regularly during the project’s design stages and construction. The architect’s responsibility is to communicate the design intent to the building constructor and, ultimately, to the building operator. Commissioning is a quality assurance tool to achieve this.

Because the contractor is usually a late arrival to the project team, an explanation of the verification and testing procedures by the commissioning agent should appear in the bid documents. This will assist bidders in evaluating the time and cost implications of a commissioning agent’s participation and the agent’s impact upon acceptance of the work.

Bid documents prepared with input from the commissioning agent should include:

- the commissioning plan, including the scope and sequence of the commissioning program;

- the commissioning specifications, including a manual with examples of verification forms and testing procedures, noting probable duration;

- any specialized documentation related to testing, such as CSA standards, which may describe options for testing methods;

- standards for submission and acceptance of:

- shop drawings;

- contractor’s tests;

- product, system, operations and maintenance manuals;

- training programs;

- post-occupancy or seasonal testing;

- the consequences of non-compliance with predefined percentages that directly relate to the schedule of values.

Component Verification

The use of performance specifications often results in the supply of components with service characteristics or operational outputs which require minor revisions to the design. The component verification process is an excellent tool to highlight these variances. The commissioning agent should prepare checklists for the verification of each construction element to be tracked, using the risk management assessment classifications, such as fundamental, critical, and essential, to record compliance with the specifications. In the case of material substitutions, variances from the specifications must include a written statement of recommendation for acceptance by the architect and the acceptance by the owner. Submittals such as shop drawings and mock-ups are documented, as are the results of tests and the receipt of manuals and warranties.

Systems Verification

The process of systems verification begins after all components within the system are accepted and deficiencies are corrected. The architect and the engineers normally agree upon contract values for items in the verification program so that the contractor is aware of the potential financial impact on progress billing applications and subsequent certificates for payment. The contractor’s schedule for the timing, sequencing, and proving of systems will require regular commissioning meetings to ensure that all parties are available to:

- verify that all prerequisites to testing are in place;

- review test procedures and acceptable results;

- witness tests.

Attendance at testing procedures by the independent commissioning agent and by the future building operator is beneficial.

Systems verification procedures may require:

- extra time due to the demonstrations of various controls;

- specialized equipment, such as:

- pressure testing;

- thermal scanning of the building envelope.

The timing and circumstances of verification and testing are often beyond the contractor’s control, as happens when testing for part of the HVAC systems must be done in a different season.

Failure to verify can seriously affect the construction schedule and can result in delays and claims. To avoid delays:

- have the trades responsible prove or test systems prior to witnessing by the commissioning agent;

- provide for trade and subtrade acceptance on verification forms prior to contractor acceptance.

After sign-off by the contractor, the consultants will then certify their recommendation of acceptance using standard verification sheets. Variances from the design identified during systems testing will require investigation and reporting by the architect and the engineers. Testing after occupancy can release the contractor from continuous attendance on the site.

Because many integrated system tests require that certain post-occupancy conditions be in place (for example, all equipment, furnishings and building users), the architect and the commissioning agent should consider preliminary or conditional testing and recommended acceptance of certain subsystems. If alteration to the design is required, it must be carefully documented, and the project database altered to suit (e.g., sequence of operation is often modified).

A recommendation by the architect or the engineer to deny acceptance of a system may result in a dispute with the contractor over the design. For this reason, the architect should always follow the method of dispute resolution in the contract.

Once conditional acceptance is established, a building operator training program can be started. Before beginning a training program, the owner’s building operator must have:

- complete and accurate operating and maintenance manuals;

- a description of the system’s intended operation;

- the warranties and information outlining maintenance contracts.

Warranty Review

The architect will be responsible for reviewing defects and deficiencies during the warranty period on behalf of the client and for notifying the contractor of items requiring attention. Prior to the anniversary date of the one-year warranty, the architect should arrange a review of the project. The review should include:

- the architect;

- the engineers;

- the client, and probably the client’s operations and maintenance personnel;

- the contractor;

- the commissioning agent (if there is one on the project).

After a review of each situation, the architect:

- directs the contractor to correct the problem as required under a typical construction contract; or

- advises the client to deal with the condition, because it is a maintenance problem.

A summary of problems and construction deficiencies should be compiled. The architect verifies the accuracy of the list and forwards it to the contractor, before the contractor’s obligations under the contract expire.

If the contractor fails to rectify a warranty item in a reasonable time, the architect may review the client’s rights under the bonding and insurance provisions in the contract.

The architect may conduct periodic reviews of the project following occupancy to confirm with the client or the client’s personnel that all systems are operating. These reviews determine how well the client’s personnel understand the operations manuals and any programmed default settings within the systems. The architect should also advise the client that alterations to any work by the client’s own forces during the warranty period may void portions of the contractor’s obligation under the contract.

During the first year of operation, it is usually necessary to confirm the performance of mechanical or electrical systems which are used primarily during a certain season of the year.

The architect must arrange for such inspection and verification with the engineers (and possibly with the commissioning agent). The contractor must demonstrate that these systems, which were conditionally accepted at the time of substantial performance, satisfy all design requirements before the architect can recommend final acceptance. The architect must document any adjustment or revision to these systems as well as modify the project database and the owner’s appropriate operating and maintenance manuals.

The architect and the contractor may be called upon to account for deficiencies uncovered during post-occupancy, either because of defective workmanship or the original design.

Post-occupancy Evaluations

Post-occupancy evaluations:

- review a building’s performance;

- assess how well the building matches users’ needs;

- identify ways to improve building design, performance and fitness for purpose;

- can be carried out at six- or 12-month intervals.

These evaluations, which are an additional service beyond the architect’s normal services, may review:

- functional performance, including:

- social and behavioural review;

- efficiency of spatial arrangements;

- technical performance such as the performance of building envelope or finishes.

When evaluating functional performance, the architect attempts to quantify and measure performance in terms of explicitly stated needs of occupants and users. Occupational therapists and social scientists have developed useful information in this field and can be hired by the architectural firm separately to provide guidance. However, many architects who are experienced programmers may also be qualified to provide valuable feedback on user needs. In many cases, these needs would have been defined in the original functional program for the project. See Chapter 6.1 – Pre-design.

Post-occupancy evaluations, which may include a technical review of the building and certain architectural components such as finishes or the building envelope, are used to develop a long-term maintenance plan or the requirements for future projects.

Post-occupancy evaluations assist clients, especially those who undertake many repeat buildings, such as retail outlets and fast-food restaurants, to determine how their future facilities may be improved and how costs may be reduced. Post-occupancy evaluations also assist in improving ergonomics and in developing new functional programs and plans for facility management, future renovations, and master plans.

Finally, the post-occupancy evaluations may review the method of project delivery and contractual arrangements to determine how to improve the design, contract documents and project management methods for future projects.

References

AABC Commissioning Group. “ACG Commissioning Guideline for Building Owners, Design Professionals and Commissioning Service Providers.” AABC Commissioning Group, 2005. https://www.commissioning.org/wp-content/themes/blankslate/commissioningguideline/ACGCommissioningGuideline.pdf, accessed June 9, 2020.

American Institute of Architects. The Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice, 15th Edition. Wiley, 2013. Chapter 12.6 - Project Closeouts, p. 593–601.

American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE). “Guideline 0-2005 The Commissioning Process.” ASHRAE Standards Committee, January 10, 2010. https://www.ashrae.org/file%20library/technical%20resources/standards%20and%20guidelines/standards%20addenda/g0_2005_a_b_c_d_final.pdf, accessed June 9, 2020.

Canadian Construction Documents Committee. CCDC2 Stipulated Price Contract. Ottawa, ON: CCDC, 2020.

Cooper, Barbara A., S. Ahrentzen, and B. Hasselkus. “Post-occupancy Evaluation: An environment-behaviour technique for assessing the built environment.” Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1991. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/13126980_Post-occupancy_evaluation_An_environment-behaviour_technique_for_assessing_the_built_environment, accessed June 9, 2020.

Ontario Association of Architects (OAA) and Ontario General Contractors Association (OGCA). “A Guide to Project Closeout Procedures.” OAA, 2010.

https://oaa.on.ca/OAA/Assets/Documents/OGCA/OAA%20OGCA%20Guide%20to%20Closeout%20Procedures.pdf, accessed September 15, 2020.