Définitions

Communication : La science et la pratique de la transmission de l’information; l’action de transmettre des nouvelles; l’information transmise; les relations sociales.

Communication relative à la construction : Dans le contexte organisationnel, transmission d’une instruction pour influencer les actions ou le comportement des autres, ou ce qui peut supposer un échange ou une demande d’information pendant la période de construction d’un projet.

Contrôle des communications : Le processus visant à assurer la satisfaction des besoins en information du projet et de ses parties prenantes (Project Management Institute).

Gestion des communications : Le processus visant à assurer la collecte, la création, la distribution, le stockage, la récupération, la gestion, le contrôle et, finalement, l’élimination de l’information du projet de manière appropriée et en temps utile.

Modes de communication : Une procédure, une technique ou un processus systématique utilisés pour le transfert de l’information parmi les parties prenantes du projet.

Négociation : Discussion formelle entre des personnes qui ont des intentions ou des buts différents par rapport à des aspects commerciaux, à la conception ou à la construction et pendant laquelle ils tentent de parvenir à une entente.

Parties prenantes : Toute personne ou tout groupe de personnes susceptibles d’exercer un impact sur les résultats d’un projet ou d’être touchées par les résultats d’un projet.

Planification des communications : Le processus d’élaboration d’une approche et d’un plan appropriés pour les activités de communication du projet en se basant sur les besoins en information de chaque partie prenante ou de chaque groupe, des ressources disponibles de la firme d’architecture et des besoins du projet (Project Management Institute).

Procès-verbal : Le relevé ou les notes prises lors d’une réunion ou d’une transaction; un bref sommaire des discussions lors d’une rencontre; une note de service officielle qui autorise ou recommande une mesure à prendre.

Introduction

« La communication est au cœur de la pratique de l’architecture. Le concepteur le plus talentueux ne pourra faire valoir ses idées s’il est incapable de les communiquer adéquatement aux autres. Le processus de construction repose sur la collaboration de nombreuses personnes et les architectes doivent être en mesure de communiquer de façon claire, concise et sans ambiguïté pour qu’un projet soit couronné de succès. »

David Greusel, AIA

On ne doit jamais sous-estimer l’importance de la parole. On sait d’ailleurs que des discours passionnés et des présentations architecturales frappantes ont inspiré la création de monuments et changé le cours de l’histoire. Néanmoins, l’architecte devrait mettre systématiquement en pratique les deux principes suivants : « dites ce que vous voulez dire » et « mettez-le par écrit ».

La pratique de l’architecture exige de bonnes communications; nombreuses sont les situations dans lesquelles elles jouent un rôle clé. Par exemple, lorsque l’architecte doit :

- expliquer les rôles et responsabilités du client, de l’architecte et des ingénieurs et autres conseils dans le projet de conception;

- déterminer les facteurs et les exigences qui assureront la réussite du projet;

- décrire les compétences, l’expérience et la proposition de valeur uniques à un client potentiel;

- élaborer et valider le programme fonctionnel ou l’énoncé des exigences d’un client;

- présenter un concept à un client aux fins de son approbation;

- expliquer un concept à la personne qui doit le dessiner;

- présenter une demande de modification de zonage à l’autorité compétente;

- résoudre un problème sur un chantier de construction.

De manière générale, les communications s’inscrivent dans deux contextes au sein de la firme d’architecture :

- les livrables du projet, y compris :

- la conception;

- les systèmes techniques et les détails du bâtiment;

- la coordination du travail de l’équipe de conception en architecture et en génie;

- l’exécution des travaux par l’entrepreneur en construction;

- la gestion du projet, y compris :

- la portée des services;

- la planification et le contrôle des coûts, du calendrier et de l’exécution du travail;

- la gestion de la qualité, des risques et des parties prenantes.

Le présent chapitre porte sur les principes de la communication efficace et décrit divers processus et techniques de communication qui aideront l’architecte à communiquer l’information du projet et à gérer les besoins des parties prenantes du projet.

Comprendre le processus de communication

Le processus de communication requiert :

- un émetteur;

- un destinataire;

- un moyen de communication;

- un message;

- une rétroaction.

Bien des facteurs ont une incidence sur la clarté, la transmission et la compréhension d’un message. La chaîne d’approvisionnement de l’industrie de la conception-construction est complexe et à multiples facettes. Elle comprend de nombreux intervenants aux intérêts, à l’éducation, à l’expérience, à l’expertise et aux langages très diversifiés. Le message d’un émetteur peut être mal compris par le destinataire une fois reçu et décodé.

Le modèle fondamental de communication utilisé aujourd’hui dans le monde entier a été développé il y a plus de 60 ans par Wilbur Schramm.

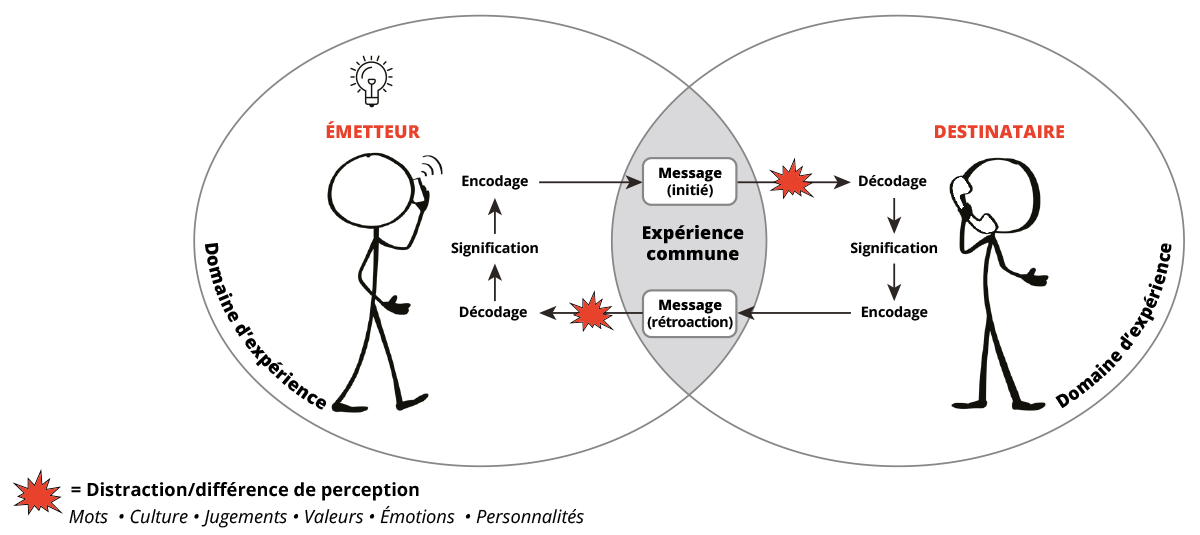

FIGURE 1 Modèle de communication de Schramm (Verma, 1996, p. 17).

[Traduction libre de l’adaptation autorisée par l’auteur Vijay K. Verma]

Le modèle de communication de Schramm désassemble le processus de communication entre l’émetteur et le destinataire, ce qui permet l’exploration de chaque facette de la communication. Il existe de nombreuses possibilités de rupture de communication, notamment, pour n’en citer que quelques-unes :

- les défis pour l’émetteur d’encoder une idée dans un langage, qu’il s’agisse de langage parlé ou de langage de dessin;

- le mauvais choix du moyen de communication, par exemple dessiner une idée alors qu’elle serait mieux exprimée par écrit, ou parler directement au client, en personne ou au téléphone, plutôt que d’envoyer un courriel;

- les filtres de perception du destinataire qui bloquent ou déforment le message de l’émetteur;

- le langage dans lequel un message est transmis n’étant pas compris par le destinataire, par exemple, lorsqu’il ne peut pas lire les dessins ou ne partage pas la même langue parlée que l’émetteur;

- la rétroaction du destinataire vers l’émetteur qui fait face aux mêmes défis que la communication de l’émetteur vers le destinataire.

Comme l’indique Schramm, l’émetteur et le destinataire doivent partager des champs d’expérience qui se chevauchent pour qu’une communication puisse être efficace. Par conséquent, l’architecte doit faire appel à ses compétences interpersonnelles pour créer un domaine d’expérience qui atteint et chevauche celui de l’intervenant du projet avec lequel il veut et doit communiquer.

Caractéristiques du processus de communication

Pour communiquer efficacement, les architectes doivent bien comprendre les caractéristiques du processus de communication. Selon Ralph Kliem, auteur du livre Effective Communications for Project Management, la communication efficace exige beaucoup de flexibilité et d’adaptabilité de la part de toutes les parties et elle est :

- un processus intégré et interdépendant;

- un processus complexe et dynamique;

- un processus continu;

- un processus subjectif.

Pourquoi est-il important que la communication soit efficace dans les projets de conception-construction?

« Les projets de construction sont complexes et risqués. Toutes les parties prenantes doivent y participer activement. La coopération et la coordination des activités par le biais de la communication interpersonnelle et de groupe sont essentielles à leur réussite. »

M.E.L. Hoezen, The Problem of Communication in Construction

Dans la publication Management of Building Projects, le Building Projects Committee de la Colombie-Britannique souligne que les communications efficaces et la bonne documentation requièrent :

- de bonnes compétences interpersonnelles pour assurer la coopération et la réussite du travail d’équipe;

- une sensibilité politique, qui peut favoriser la conclusion d’accords en temps utile;

- la capacité de transmettre les messages clés et d’élaborer des solutions (lors de présentations à divers publics – entreprises, municipalités ou collectivités);

- des compétences rédactionnelles et graphiques pour diffuser l’information en temps utile, pour spécifier et coordonner le travail et son avancement.

Dans « Why Is Communication Important in Construction Projects? » Neal Flesner souligne que les communications efficaces :

- favorisent l’établissement et le maintien de relations dans les projets de construction;

- favorisent le partage d’idées et l’innovation;

- contribuent à établir la confiance et à renforcer les équipes;

- améliorent la gestion de l’équipe;

- créent des boucles de rétroaction;

- donnent des résultats.

Chacune de ces exigences pour une communication efficace renvoie au modèle de communication de Schramm et à la nécessité de tenir compte tous les aspects du processus de communication.

Gestion des communications d’un projet

« La gestion des communications d’un projet comprend les processus nécessaires pour assurer la satisfaction des besoins d’information du projet et de ses parties prenantes par le développement d’activités conçues pour parvenir à un échange d’informations efficace. » [Traduction libre.]

A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Sixth Edition

Processus de gestion des communications d’un projet

L’ouvrage A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge du Project Management Institute capte tous les aspects de la gestion des communications d’un projet dans les trois processus suivants :

- la planification des communications;

- la gestion des communications;

- le contrôle des communications.

Planification des communications

Comme tous les autres processus de gestion de projet, la communication doit être planifiée. Qui doit recevoir quelle information, quand, dans quel format, sur quel support? Le défaut d’une telle planification expose à de graves erreurs de jugement, à des malentendus, à de la méfiance et même à la rupture de relations, car les processus de communication ne relèvent pas du hasard ou de la tradition.

Un plan de communication devrait saisir les besoins de communication de toutes les parties prenantes du projet, y compris l’organisation cliente, l’équipe de conception, l’équipe de construction et les parties prenantes externes, telles que les autorités compétentes.

À un haut niveau, la planification des communications exposée dans la publication Management of Building Projects comprend :

- la définition du projet;

- le choix et la description du mode de réalisation du projet;

- l’attribution du rôle et des responsabilités des parties prenantes du projet;

- le contrôle systématique de la portée, de la qualité, du coût et du calendrier du projet.

Ces quatre activités de projet peuvent être décomposées à des niveaux de détail plus importants dans la structure de répartition du travail (SRT) du projet. Le format du plan de communication peut prendre plusieurs formes; toutefois, une approche simple consiste à commencer par la structure de répartition du travail du projet et se demander pour chaque livrable, sous-livrable ou tâche : « De qui dois-je obtenir des informations à ce sujet? » et « Qui doit recevoir des informations à ce sujet? » Une structure de répartition du travail bien développée fournira une base solide pour la planification des communications, favorisera la transparence et évitera que des questions importantes ne passent entre les mailles du filet.

L’utilisation de la structure de répartition du travail comme outil fondamental dans la planification des communications suppose l’établissement d’un lien entre le travail du projet et les parties prenantes du projet. Chaque intervenant du projet a des besoins d’information. Ces besoins peuvent être saisis au niveau élevé (les livrables), au niveau intermédiaire (les sous-livrables) ou au niveau détaillé (les tâches). L’élaboration du plan de communication devient alors un exercice consistant à se poser les questions suivantes pour chaque partie prenante ou groupe de parties prenantes :

- de quelles informations la ou les parties prenantes ont-elles besoin de la part de l’architecte concernant ce livrable (informations de haut niveau), ce sous-livrable (informations de niveau moyen) ou les tâches (informations détaillées)?

- de quelles informations l’architecte a-t-il besoin de la part des parties prenantes concernant ce livrable (informations de haut niveau), ce sous-livrable (informations de niveau moyen) ou les tâches (informations détaillées)?

- sous quel support, sous quel format et avec quelle fréquence les informations doivent-elles être communiquées?

Un plan de communication simple créé autour de la structure de répartition du travail aidera toute l’équipe de conception à gérer les informations tout au long du cycle de vie du projet. Cette approche permettra également de modifier le plan de communication à mesure que d’autres parties prenantes seront identifiées et que leurs besoins seront analysés.

Voir le Manuel de pratique canadien pour la MDB, volume 3 – Contexte du projet, chapitre 7 – Portée, priorités et engagement, qui traite des communications du projet en contexte de modélisation des données du bâtiment.

Gestion des communications

« Le processus [de gestion des communications] assure la collecte, la création, la distribution, le stockage, la récupération, la gestion, le suivi et la disposition finale des informations relatives au projet en temps utile et de manière appropriée. » [Traduction libre.]

Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Sixth Edition

La gestion de la communication d’un projet suppose la circulation de l’information conformément au plan de communication. Comme indiqué ci-dessus, les communications de projet s’établissent dans les deux contextes suivants : les informations sur les livrables du projet et les informations sur la gestion du projet. Ces deux contextes impliquent une communication interne et externe.

L’architecte dispose de divers outils de communication pour gérer le projet, y compris :

- les rapports sur la performance :

- les écarts entre les activités prévues de prestation de services de conception, y compris la portée, le coût et le calendrier, et les performances réelles de l’équipe de conception;

- les projections de performance du projet quant au travail, au coût et au calendrier;

- les interventions de gestion nécessaires pour ramener les performances du projet au niveau du plan ou pour proposer des changements au plan du projet;

- les rapports sur l’avancement du projet selon le calendrier :

- un plan d’étape qui indique les résultats obtenus à certaines dates critiques;

- un calendrier détaillé qui indique le travail entrepris et terminé par rapport au travail prévu;

- les rapports sur les coûts :

- montants budgétés et dépenses réelles.

En matière de communication, la préoccupation première ne doit pas être ce que l’on veut dire, mais plutôt ce que l’on veut faire comprendre au destinataire.

Contrôle des communications

L’architecte doit contrôler toutes les communications liées au projet et s’assurer que les informations circulent comme prévu tout au long du projet. Ce contrôle permet d’éviter des problèmes majeurs si l’architecte peut réagir et prendre immédiatement les mesures appropriées. Souvent, les gens retiennent ou interrompent la communication d’informations s’ils craignent qu’elles leur nuisent ou qu’elles nuisent à la réussite du projet. L’architecte doit s’assurer que les équipes communiquent et coopèrent en temps utile pour éviter les mauvaises surprises à toutes les parties.

Une approche traditionnelle de contrôle de l’efficacité de la communication consiste en un processus d’audit facilité par la gestion sur le terrain (appelée « management by walking around »). Cette méthode consiste à s’entretenir avec les membres de l’équipe et les parties prenantes sur une base continue, mais informelle et à leur demander s’ils ont bien reçu les informations et s’ils y ont donné suite en temps utile et dans un format approprié.

Trois modes de communication

Les architectes ont de tout temps communiqué par des dessins. La technologie évoluant sans cesse, ils doivent maintenant adopter et intégrer diverses formes de communications et technologies de l’information, y compris l’Internet, la vidéo, l’audio et le logiciel de présentation. Les modes de communications traditionnels sont les suivants :

- les communications écrites;

- les communications verbales (parler et écouter);

- les communications graphiques.

Communications écrites

Il est facile de surveiller et de contrôler les communications écrites distribuées sur papier ou par des moyens électroniques. Les firmes d’architecture ont besoin de personnes qui possèdent d’excellentes compétences rédactionnelles, non seulement pour les services où la rédaction est primordiale, comme les études et les rapports, mais aussi pour la correspondance, les procès-verbaux, le marketing et les présentations.

Communications écrites : propositions, rapports et correspondance

Les communications écrites peuvent être formelles ou informelles. Les communications informelles comprennent les courriels, les mémos, les tweets et les réponses électroniques rapides à contenu limité. Elles se veulent courtes et directes, et visent à communiquer une ou plusieurs idées. Les communications écrites formelles comprennent les accords, les lettres demandant ou fournissant des informations spécifiques ou complètes, les présentations, les propositions et les devis, ainsi qu’une multitude de rapports, de documents de planification de projet, de rapports de visites de chantier et de documents de modification à l’ouvrage.

Voici quelques conseils pour une communication écrite efficace :

- Propositions : Une proposition bien structurée et bien rédigée donnera au client une impression de la capacité d’un architecte à organiser et à exécuter un projet. Lorsque vous répondez à un appel de propositions, soyez précis quant à la langue et à l’ordonnancement de la proposition. Le format de la proposition doit suivre la structure de l’appel de propositions du client. Les clients imposent souvent une limite quant au nombre de pages des propositions. Certains pourront n’accorder aucune attention à des propositions beaucoup trop longues; il arrive même que certains comptent le nombre de pages autorisées et arrachent les pages excédentaires sans même les examiner.

- Rapports :

- Rapports écrits : Il est important de consigner toutes les transactions professionnelles et d’affaires par écrit, tant pour la gestion de la firme que pour la gestion de tous les projets. Des dossiers clairs, écrits et complets peuvent être d’une valeur inestimable pour la résolution des litiges, et constituent la meilleure défense dans le cadre d’une action en justice; chaque dossier fera l’objet d’un examen détaillé par les avocats des deux parties en cas de procès.

- Notes de service et courriels : Tous les documents, tant entrants que sortants, ainsi que les notes de service internes et les courriels, doivent être datés et porter le nom et le numéro du projet. La date figurant sur la correspondance crée une chronologie précise des événements au cours d’un projet, tels que l’ordre dans lequel les croquis ont été créés ou le moment où des instructions supplémentaires ont été transmises.

- Correspondance : La discipline consistant à rédiger la correspondance dans un langage clair, complet et concis permettra de tenir des dossiers précis et de renforcer la capacité d’écrire en tenant compte du destinataire.

- Rapports de chantier : Les rapports de chantier sont des documents officiels qui fournissent un compte rendu des observations, des écarts entre les documents de construction et la construction réelle, et des mesures à prendre. Ils doivent être précis et documenter tous les systèmes du bâtiment, ne serait-ce que pour dire : « Observé – pas de commentaire pour le moment ».

La documentation écrite organisée dans un système structuré est essentielle à la reconstitution des événements qui ont abouti à la prise de décision. La chronologie des événements peut devoir être recréée des années après que toutes les personnes impliquées dans un projet aient quitté la firme (et peut-être la ville, la province ou le pays) ou soient décédées. Même les plus petites firmes ont maintenant accès à des systèmes de gestion de l’information sur les projets électroniques et basés sur le Web qui facilitent la catégorisation, l’archivage et la recherche d’informations.

Voir le chapitre 6.8 – Modèles de formulaires pour la gestion du projet pour des modèles de formulaires relatifs aux communications externes et notamment des modèles de :

- notes de service;

- procès-verbaux de réunions;

- bordereaux de transmission;

- répertoire des membres de l’équipe de projet;

- rapports de chantier.

Communications verbales

Écouter

Dans les communications verbales, il est essentiel de bien maîtriser les principes de « l’écoute active » pour comprendre la nature d’un problème et la portée des services requis.

L’écoute active comprend :

- l’observation, en prêtant attention aux gestes, aux idées, aux sentiments et aux intentions de la personne qui parle;

- l’amplification, en demandant plus d’information;

- le reflet, en exprimant en d’autres termes ou en paraphrasant les remarques de la personne qui parle;

- la clarification, en recherchant une compréhension plus approfondie ou en demandant des précisions;

- l’interprétation, en suggérant une conclusion à une remarque;

- la synthèse, en résumant la discussion

En renforçant ses compétences en « écoute active », l’architecte améliore la qualité de ses services et s’attire un plus grand respect de ses clients.

Par ailleurs, les différends au sein de l’industrie de la construction (et cela vaut en fait pour la plupart des différends) découlent généralement d’un malentendu; d’où l’importance d’adopter une attitude appropriée et de bien écouter et comprendre son interlocuteur. L’architecte saura ainsi identifier les exigences cruciales d’un projet et prévenir les conflits.

Parler

La plupart des architectes sont conscients que d’autres éléments que les mots prononcés participent à la transmission du message. Le ton de voix et le langage corporel font aussi partie de la communication. La transmission efficace d’un message exige une attention constante à tous ces différents moyens de communication et la volonté de mettre en pratique et d’affiner ses talents de communicateur.

Voici quelques conseils pour une communication verbale efficace :

- étudier l’environnement et confirmer :

- l’endroit où l’on se placera;

- l’endroit où le matériel visuel sera placé;

- les éclairages possibles;

- la relation que l’on aura avec l’auditoire;

- utiliser un langage simple, non technique;

- parler fort et bien articuler;

- faire une répétition en utilisant un vidéo;

- exagérer ses gestes;

- avoir un bon maintien;

- établir un contact visuel;

- éliminer le marmonnement ou les mots inutiles (comme « en fait », « je veux dire », « heu »);

- faire des pauses fréquentes.

Il est de bonne pratique de supposer que certaines personnes à qui vous vous adressez aient des problèmes d’audition non apparents. Par conséquent, la clarté du discours, le fait de diriger sa voix vers le public, l’exactitude des mots et le maintien d’un contact visuel avec les personnes présentes donnent confiance, tout en permettant à chacun d’entendre la présentation sans effort.

Communications graphiques

En se référant au modèle de communication de Schramm (Figure 1 ci-dessus), l’émetteur et le destinataire doivent respectivement coder et décoder le message. Si le destinataire ne connaît pas la langue parlée ou écrite de l’émetteur, il est immédiatement évident que la communication entre les deux sera inefficace. Toutefois, il n’est pas toujours évident que le destinataire d’un message graphique est incapable de « lire » des dessins. Comme la langue parlée et écrite, les dessins ont des conventions et une symbolique. Contrairement à la langue écrite et parlée, ils ont de multiples cotes, échelles et perspectives. Ajoutez à cela le caractère abstrait et parfois déroutant de l’espace multidimensionnel exprimé en plans, coupes et élévations, et vous comprendrez qu’il est fort possible qu’un intervenant non initié comprenne mal le message graphique des dessins.

Voici quelques conseils pour une communication graphique efficace :

- identifier les capacités de communication des parties prenantes, tant sur le plan du contenu que des modalités, pour recevoir et comprendre des informations graphiques;

- identifier le message qui doit être communiqué et limiter les informations graphiques nécessaires pour soutenir ce message;

- ne pas supposer que tout le monde peut lire les dessins, notamment en ce qui concerne l’interprétation de l’échelle, des volumes, des systèmes et des symboles de dessin;

- fournir des dessins des mêmes espaces et caractéristiques à des échelles différentes en montrant progressivement plus de détails;

- envisager de fournir des maquettes et des modèles virtuels.

Communications efficaces aux diverses phases d’un projet

« Les bonnes communications ne se font pas automatiquement dans les projets de construction. Il faut les entretenir du début à la fin du projet. »

Associated General Contractors of America, Guidelines for a Successful Construction Project

La façon dont les architectes communiquent avec les parties prenantes du projet reflète leur personnalité, leurs croyances, leurs valeurs et leurs préférences. Les architectes doivent éviter d’émettre des directives à sens unique, et être conscients que la communication n’est efficace que si les parties à qui elle s’adresse en ont une compréhension claire et convaincante. Les architectes doivent toujours :

- donner des instructions claires, concises et applicables en premier lieu;

- par un appel téléphonique ou un courrier électronique de suivi, demander au(x) destinataire(s) de la communication s’ils ont besoin d’éclaircissements ou d’informations supplémentaires;

- éviter d’utiliser une terminologie et un jargon architectural que les destinataires pourraient ne pas comprendre.

Cette section décrit les techniques permettant d’améliorer la communication au cours des différentes phases du projet afin de permettre à l’architecte de prendre des décisions en temps utile.

Phase préalable à la conclusion d’une entente

Le rôle et les responsabilités de l’architecte en matière de communication, comme définis dans les contrats types, comme le Document Six de l’IRAC, portent sur deux types de services, les « services de base » et les « services supplémentaires ». Ces services sont traités au chapitre 3.9 – Services d’architecture et honoraires, y compris pour les premières phases de la conception. L’architecte négocie avec le client pour savoir quels services sont des services de base et quels services sont des services supplémentaires (aux services de base). Par exemple, l’analyse du « coût du cycle de vie » est généralement un service supplémentaire, et non un service de base.

Pour les projets plus complexes, comme ceux qui sont réalisés en mode de design-construction ou de gérance de construction, le client devrait retenir les services d’un conseiller en construction pour participer au processus de conception et le conseiller sur les ressources de construction disponibles, les matériaux, l’établissement du calendrier, les considérations climatiques, etc. Voir les contrats de gérance de construction CCDC 5A, Contrat de gérance de construction – pour services et CCDC 5B, Contrat de gérance de construction – pour services et construction pour connaître les conditions de gestion préalables à la construction. Voir aussi le chapitre 5.1 – Gestion du projet de conception.

Phase des études préconceptuelles

Le chapitre 6.1 traite des communications entre l’architecte et le maître de l’ouvrage à la phase des études préconceptuelles. La Formule canadienne normalisée de contrat pour les services de l’architecte (le Document Six de l’IRAC) énonce dans ses exigences de programme fonctionnel que le client doit transmettre à l’architecte ses exigences pour le projet.

Si le client a des difficultés à fournir les exigences du projet, l’architecte doit préparer le programme fonctionnel en tant que service supplémentaire, en utilisant les services d’autres professionnels de la conception (tels que des ingénieurs) à cette étape pour déterminer les renseignements à utiliser dans les phases de conception ultérieures.

Phases de l’esquisse et du projet préliminaire

Lorsque le client engage directement un ingénieur ou autre consultant, l’architecte doit exiger d’assurer lui-même les communications et la coordination du travail de celui-ci. C’est essentiel, car l’architecte est le concepteur principal et il est responsable de la conception globale. Certaines autorités compétentes exigent d’ailleurs que l’architecte certifie qu’il est le professionnel coordonnateur attitré et qu’il coordonnera le travail des ingénieurs et autres consultants, indépendamment des relations contractuelles ou de la manière dont l’équipe de consultants est constituée. L’architecte doit impliquer le client ou les autres parties prenantes dans les décisions de conception pendant et après la conception préliminaire. Cela se fait par une communication directe avec le client ou les autres parties prenantes.

Voir aussi les chapitres 6.2 – Esquisse et 6.3 – Projet préliminaire.

Phase du projet définitif – Dessins et devis

Il est important de s’assurer que les contrats, les dessins, les devis et les dossiers soient clairs et complets – tous ces documents sont au cœur des communications écrites du projet. Cela comprend les compromis entre la conception et le coût en temps.

Voir le chapitre 6.4 – Projet définitif – Dessins et devis.

Phase de l’attribution du contrat de construction

Si l’architecte est tenu de participer à la phase de l’attribution du contrat de construction (traditionnellement appelée phase de « l’appel d’offres »), il est important qu’il établisse, en collaboration avec le client, les critères de sélection de l’entrepreneur et ceux des communications. L’objectif est de s’assurer que :

- les critères répondent à l’ensemble des objectifs du projet;

- la portée des services, les responsabilités et les risques à attribuer, ainsi que l’équilibre entre la qualité, le coût et le calendrier soient communiqués et indiqués dans les documents d’attribution du contrat.

Voir aussi le chapitre 6.5 – Attribution du contrat de construction.

Ordre de démarrage des travaux

Cet avis (l’ordre de démarrage des travaux à un entrepreneur) du maître de l’ouvrage à l’entrepreneur retenu est la première communication officielle en vertu du contrat de construction. Comme la négociation des dispositions du contrat peut prendre quelque temps, cet avis permet le démarrage des travaux avant la signature du contrat.

Phase de l’administration du contrat

La communication joue un rôle clé dans la résolution des problèmes liés à l’établissement du calendrier, à l’examen des dessins d’atelier, aux avenants de modification et aux problèmes sur un chantier de construction. La communication pendant la construction exige le maintien d’un bon équilibre entre l’obligation de répondre rapidement et celle d’examiner attentivement l’instruction ou la modification.

Aujourd’hui, il existe de nombreuses solutions matérielles et logicielles technologiquement avancées pour aider les équipes de conception, de construction et de gestion à communiquer pendant l’exécution de l’ouvrage. Nombre de ces solutions permettent une communication en temps réel entre les parties, ce qui réduit les temps de réaction aux problèmes de chantier et qui permet de limiter les retards dans le calendrier. Grâce à ces outils, les architectes présents sur les chantiers peuvent communiquer facilement et rapidement avec le personnel de conception, technique et administratif de leurs bureaux, ainsi qu’avec les ingénieurs, les spécialistes et le personnel de construction impliqués dans le projet.

Voici quelques conseils qui aideront l’architecte à maintenir de bonnes communications avec les entrepreneurs. L’architecte devrait :

- relire le contrat et les documents du projet définitif avant de répondre à une question;

- formuler aussi clairement que possible les informations ou les instructions supplémentaires dont l’entrepreneur a besoin;

- confirmer promptement par écrit toutes les communications verbales;

- noter toutes les conversations téléphoniques avec l’entrepreneur dans les dossiers du projet.

Réunion de démarrage du projet de construction

Il est essentiel de convoquer une réunion de démarrage du projet de construction. Cette réunion, présidée par le constructeur, qu’il s’agisse d’un entrepreneur général, d’un design-constructeur ou d’un gérant de construction, établit les attentes et présente le plan du constructeur pour le projet. Le maître de l’ouvrage peut avoir de l’expérience dans les projets de construction, mais ce n’est pas toujours le cas. En tant que principale partie prenante, il doit être présent afin de comprendre son rôle dans le projet de construction. L’ordre du jour de cette réunion de démarrage sera unique pour chaque projet, mais comprendra, au minimum, les points suivants : les niveaux d’autorité; les principales parties prenantes; les canaux de communication; les processus d’examen des demandes de renseignements et des documents ou autres éléments soumis; l’accès au chantier; les heures de travail; les questions liées au bruit; la facturation; etc. Les résultats de cette réunion doivent être documentés pour référence future.

Examen des dessins d’atelier

Les dessins d’atelier sont dérivés des dessins d’exécution et sont examinés par les professionnels de la conception pour vérifier leur conformité aux exigences de conception.

En communiquant les processus et les procédures d’examen des dessins d’atelier, l’architecte doit établir une pratique systématique de transmission et de consignation de tous les dessins soumis, des réponses, des éclaircissements et des instructions de modification qui sont envoyés officiellement aux professionnels chargés de l’examen des dessins d’atelier et aux fournisseurs et par leur intermédiaire.

Gestion des modifications

Les avenants de modification et les documents qui les précèdent, les projets de modification, deviennent partie intégrante du contrat et doivent être clairement communiqués. L’architecte doit fournir en temps utile des informations précises sur la cause ou la raison de la modification, puis en informer le maître de l’ouvrage et tous les ingénieurs et autres consultants. Le maître de l’ouvrage doit approuver tous les avenants de modification avant qu’ils ne soient mis en œuvre sur le chantier. Toute modification du coût, du délai d’exécution ou de la qualité de l’ouvrage est une source de préoccupation pour le maître de l’ouvrage et peut présenter un risque pour l’équipe de conception. Par conséquent, tous les aspects de ce processus doivent être consignés et soigneusement administrés.

Voir le chapitre 6.8 – Traitement des avenants de modification.

Communications et réunions de chantier

Les réunions de coordination de chantier sont généralement présidées et consignées par le gestionnaire de projet, le gérant de construction ou le chef de chantier. L’architecte doit comprendre le sens sous-jacent de certaines communications sur le chantier et agir rapidement sur toutes les questions qui impliquent l’architecte ou les ingénieurs.

Voir le chapitre 6.6 – Administration du contrat – Tâches de bureau et de chantier.

Phase de la clôture du projet

Les mesures qui suivent contribuent au maintien de communications efficaces à la clôture du projet :

- impliquer tous les participants au projet et toutes les parties prenantes;

- utiliser une liste de contrôle pour s’assurer que tous les éléments importants ont été réalisés;

- tenir à jour une liste des déficiences qui est continuellement partagée avec l’entrepreneur;

- convoquer une séance post-mortem;

- préparer des dossiers écrits, des rapports et des comptes rendus de réunions à la clôture du projet.

Voir aussi le chapitre 6.7 – Réception, mise en service et évaluations post-occupation.

Gestion des communications dans des situations particulières

Gestion des conflits

La chaîne d’approvisionnement de la conception-construction est complexe et compte de nombreux acteurs ayant des antécédents, des connaissances et des intérêts différents. L’industrie de la conception-construction est connue pour la force et la détermination de ses acteurs. Les conflits sont fréquents, et la gestion des situations conflictuelles exige des compétences analytiques et interpersonnelles. Il est important que l’architecte soit conscient que les sources de conflit dans les projets sont prévisibles, en fonction de la phase du projet.

Les sources de conflits dans les projets sont prévisibles. Les conflits entre les différentes priorités du projet sont importants au début du projet et diminuent au cours du cycle de vie du projet. Les préoccupations relatives au calendrier se font sentir tout au long de l’exécution du projet et s’accentuent vers la clôture du projet. Les conflits interpersonnels et les problèmes de main-d’œuvre ont tendance à s’aggraver au cours du cycle de vie du projet. L’architecte avisé surveille de près les sources de conflit, s’efforce de diriger les communications dans les domaines susceptibles de générer des conflits et établit des déclencheurs qui aideront à identifier le conflit qui se pointe à l’horizon. Il doit être proactif.

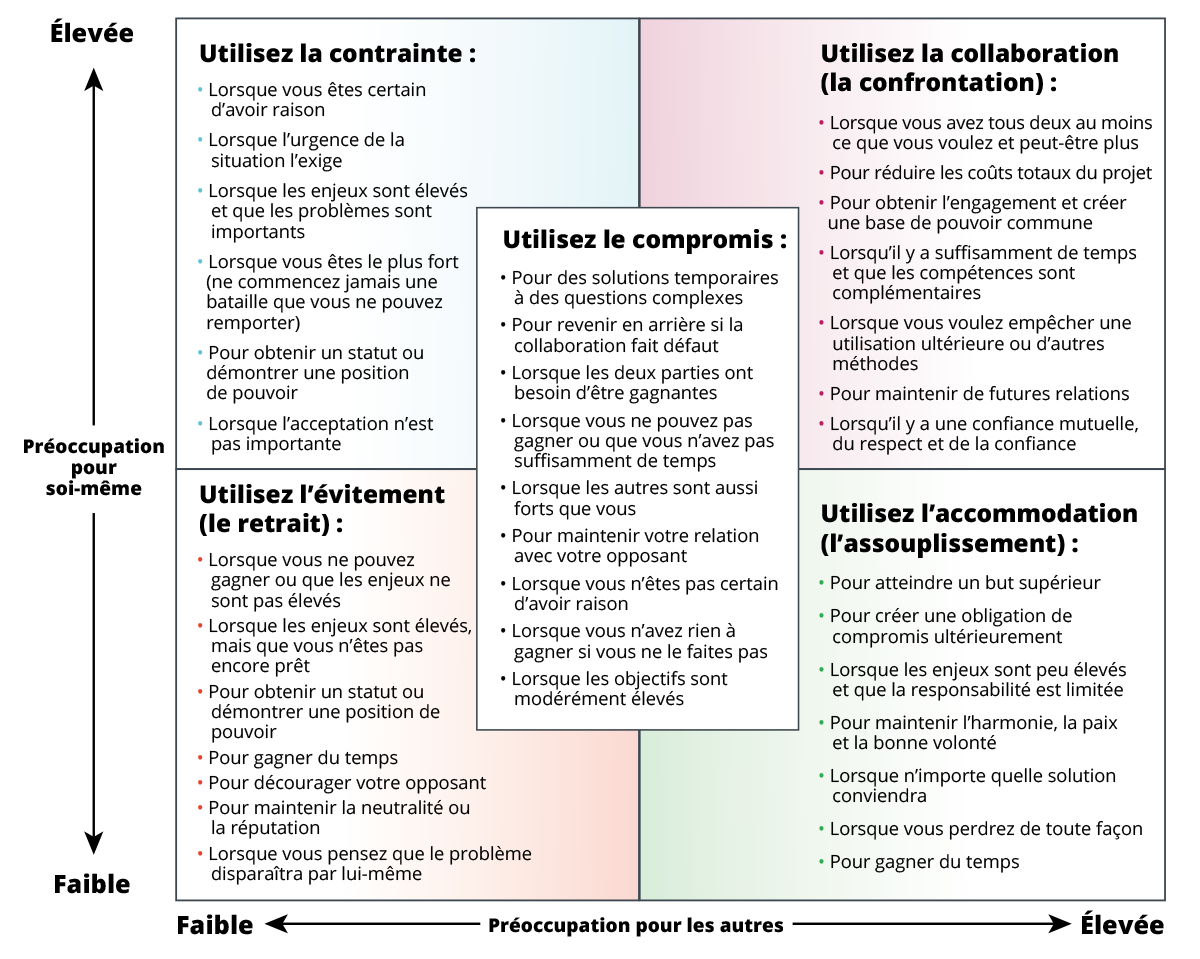

L’architecte dispose de nombreux outils pour l’aider à gérer les situations de conflit. Cependant, de nombreux chercheurs qui étudient les facteurs humains de la gestion de projet ont développé des modèles qui utilisent le même principe de base : l’application d’une des cinq approches de Blake et Mouton pour gérer les conflits, appropriée à une situation donnée et au résultat souhaité. La tâche de l’architecte consiste à déterminer ce qui est important dans la situation et à exercer ses compétences interpersonnelles pour y apporter une solution. Les stratégies ci-dessous sont adaptées des travaux de plusieurs chercheurs dans le domaine de la dynamique humaine en mettant l’accent sur les conflits dans l’environnement du projet.

Cinq stratégies de gestion des conflits

D’autres chercheurs ont adapté les cinq stratégies de résolution des conflits de Blake et Mouton au fil du temps; toutefois, l’approche de base demeure le fondement pour comprendre la résolution des conflits.

Accommodation/ Assouplissement :

- renforcer le positif et maintenir l’harmonie;

- minimiser le conflit;

- temporaire.

Évitement/retrait :

- refuser de gérer le conflit;

- utilisé lorsqu’un délai de réflexion s’impose pour prendre du recul par rapport au conflit;

- solution temporaire.

Contrainte :

- appliquer le pouvoir pour résoudre les problèmes lorsqu’il n’y a pas de terrain d’entente;

- résolution rapide au prix de la relation.

Compromis :

- négocier pour que les deux parties soient satisfaites;

- un compromis peut entraîner une réduction de la qualité ou de la portée du projet.

Collaboration/ confrontation :

- affronter le problème et travailler à une solution optimale pour les deux parties;

- solution obtenue avec une relation plus forte entre les parties;

- nécessite du temps pour analyser le problème, développer des alternatives et choisir la meilleure solution.

Chaque stratégie est appropriée dans une situation donnée; cependant, les stratégies ne donnent pas toutes un résultat durable. L’application appropriée de ces cinq modes repose sur une comparaison entre le résultat souhaité pour soi-même et le résultat souhaité pour les autres. K.W. Thomas développe les cinq stratégies en les plaçant dans une matrice qui met en relation les stratégies de conflit avec la valeur de ses propres objectifs par rapport aux relations avec les autres.

FIGURE 2 Application des stratégies de résolution des conflits (Verma, 1996, p. 122). Traduction libre d’un tableau reproduit avec la permission de l’auteur, Vijay K. Verma.

Négociation

La négociation est un volet essentiel des communications pour un architecte qui, surtout s’il est patron, doit comprendre les techniques élémentaires de négociation qui permettent d’en arriver à des ententes satisfaisantes avec :

- les clients;

- les entrepreneurs;

- les ingénieurs et autres consultants;

- le personnel;

- les fournisseurs, etc.

De nombreux livres et instruments médiatiques expliquent les techniques de négociation, et tout patron devrait s’y intéresser. La plupart conseillent de rechercher une solution « gagnant-gagnant » — un échange juste et raisonnable qui permet aux deux parties de se retrouver en meilleure position qu’elles ne l’auraient été sans une entente.

Dans toute négociation, il y a trois facteurs critiques :

- le temps;

- le pouvoir;

- l’information.

Il est important de se rappeler que le prix n’est pas toujours l’enjeu le plus important. Par ailleurs, les objectifs visés peuvent différer d’une personne à l’autre. La négociation ne devrait jamais se limiter à la discussion d’un seul point.

Plusieurs prétendent que certains facteurs matériels comme la disposition des sièges et le langage corporel peuvent être des éléments de communication non négligeables dans une négociation. Il est important d’apprendre et de comprendre les tactiques de négociation. Voir Mastering the Business of Design (intitulé en Ontario Mastering the Business of Architecture) pour une explication de ces tactiques.

Une négociation réussie présente les caractéristiques suivantes :

- chaque partie a l’impression d’être arrivée à ses fins;

- chaque partie estime que l’autre a été juste et a fait montre de considération;

- chaque partie serait prête à traiter avec l’autre à nouveau;

- chaque partie a confiance que l’autre va honorer ses engagements.

Parties prenantes et communications

Communications externes

Dans le contexte du présent chapitre, les communications externes sont celles qui mettent en cause des personnes de l’extérieur de la firme d’architecture. Dans toute communication concernant la firme, l’architecte doit :

- être professionnel;

- être courtois et agir avec tact;

- savoir écouter (écoute active);

- respecter le caractère confidentiel des informations relatives aux clients et à la firme

Selon le Building Projects Committee de la Colombie-Britannique, dans la publication Management of Building Projects, la portée des communications externes est une question de jugement. Il est important que l’architecte apprenne et comprenne :

- dans quelle mesure communiquer et avec qui;

- si la communication doit être écrite ou verbale;

- dans quelle mesure les communications verbales des réunions ou autres conversations doivent être confirmées par écrit, et si le compte rendu écrit doit faire l’objet d’un accusé de réception ou d’un accord, ce qui est généralement nécessaire pour établir les transmissions de dessins ou les comptes rendus de réunions.

Clients

L’architecte doit aider son client à prendre des décisions éclairées; l’établissement de rapports personnels est donc important. Pour créer et maintenir une bonne relation avec un client, on doit :

- être un adepte de l’écoute active (voir ci-dessus);

- toujours utiliser un langage simple et direct;

- être honnête, ce qui comprend notamment :

- faciliter la résolution des problèmes;

- être disposé à admettre que l’on ne connaît pas la réponse à une question, mais s’engager à la trouver;

- proposer des solutions plutôt que des problèmes;

- se mettre à la place du client (par exemple, ne pas s’attendre à ce qu’il comprenne les dessins facilement, les architectes ont la formation pour lire les dessins, mais pas les clients);

- documenter exhaustivement toutes les décisions concernant un projet et faire confirmer leur exactitude;

- reconnaître que le client a le droit et la responsabilité de prendre les décisions majeures concernant le projet.

Plus la relation entre l’architecte et le client sera harmonieuse et solide, plus il sera facile de surmonter les différends qui pourront survenir pendant la conception et la construction du projet.

Voir aussi le chapitre 2.2 – Le client.

Ingénieurs et consultants

Qu’ils soient engagés par l’architecte ou directement par le client, les ingénieurs et consultants sont les coéquipiers de l’architecte. L’objectif de l’équipe est de fournir au client un projet de bâtiment qui réponde à ses besoins.

Lorsqu’il communique avec les ingénieurs et consultants, l’architecte doit :

- s’assurer qu’ils sont immédiatement informés de tout développement qui les concerne;

- s’assurer qu’ils ont intégré les modifications, ajouts ou suppressions aux documents du projet;

- documenter exhaustivement toutes les décisions prises au sujet du projet et confirmer leur exactitude;

- comprendre toutes les recommandations faites par les consultants.

Voir aussi le chapitre 2.3 – Ingénieurs et autres consultants.

Entrepreneurs

Les documents de construction constituent le principal moyen de communication avec l’entrepreneur. Au moment de leur préparation, l’architecte doit constamment se rappeler qu’ils sont un outil de communication et qu’il doit les regarder du point de vue de l’entrepreneur.

Il doit s’assurer qu’ils répondent bien aux questions suivantes :

- L’information est-elle facile à trouver?

- L’information est-elle claire?

- Est-ce que les documents comportent des renvois pour assurer l’exhaustivité et la clarté de l’intention conceptuelle?

- Est-ce que les conditions et éléments inhabituels et les détails de construction sont indiqués et décrits?

Lorsque les documents de l’appel d’offres sont clairement rédigés :

- les soumissions sont plus précises;

- les addendas sont moins nombreux durant le processus d’appel d’offres;

- l’écart entre la plus basse et la plus haute soumission est moins élevé;

- le constructeur et les sous-traitants comprennent mieux l’intention conceptuelle;

- le chantier accuse moins de retards;

- le coût final est moins élevé pour le client (moins d’avenants de modification);

- le bâtiment est de meilleure qualité.

Quel que soit le soin apporté à la préparation des documents, l’architecte doit s’attendre à ce que l’entrepreneur ait besoin d’éclaircissements pendant l’exécution des travaux.

La bonne communication avec l’entrepreneur exige un équilibre entre la nécessité de fournir des réponses rapides et celle de bien réfléchir avant d’émettre une directive ou d’amorcer une modification. Il y a lieu, par exemple :

- de relire le contrat et les documents de construction avant de répondre à une question;

- de formuler aussi clairement que possible les instructions dont l’entrepreneur a besoin;

- de confirmer promptement par écrit toutes les communications verbales, en utilisant un des moyens suivants :

- les procès-verbaux de réunion;

- les instructions supplémentaires;

- les avenants de modification;

- les directives de modification;

- la correspondance;

- les rapports de visite de chantier;

- prendre note de chaque conversation téléphonique avec l’entrepreneur pour mettre aux dossiers.

Voir aussi le chapitre 6.6 – Administration du contrat – tâches de bureau et de chantier.

Autorités compétentes

Les autorités compétentes constituent un groupe de parties prenantes clés dans les projets de conception et de construction. Il peut y avoir plusieurs autorités à plusieurs ordres de gouvernement impliquées, y compris des individus et des comités ayant un intérêt dans la planification du site, le zonage, l’examen des plans, l’inspection du chantier, les terres de conservation, la circulation, la gestion des eaux et les services publics. Chacune de ces autorités peut avoir un niveau d’influence important. Les niveaux d’intérêt pour les objectifs du projet peuvent quant à eux varier du tout au rien.

Pour satisfaire aux besoins de communication des autorités compétentes, il est important d’avoir une certaine conscience politique. Demandez-vous :

- Quels sont les facteurs qui amènent l’autorité à prendre une décision par rapport au projet?

- De quelle information l’autorité a-t-elle besoin?

- Comment puis-je présenter l’information pour tenir compte de son domaine d’intérêt?

Adaptez les stratégies de communication utilisées avec les clients :

- favorisez « l’écoute active »;

- utilisez un langage simple dans toutes les communications;

- soyez honnête, ce qui comprend :

- efforcez-vous de faciliter la résolution des problèmes;

- soyez prêt à admettre que vous ne connaissez pas une réponse, mais promettez de la trouver;

- proposez des solutions plutôt que des problèmes;

- documentez soigneusement toutes les décisions reliées à un projet et confirmez leur exactitude;

- reconnaissez le droit et la responsabilité de l’autorité de prendre des décisions dans l’intérêt de son organisation.

Voir aussi le chapitre 2.4 – Autorités compétentes.

Autres parties prenantes

Il peut y avoir bien d’autres groupes de parties prenantes impliquées dans la conception et la construction des bâtiments, notamment, les voisins du projet, les locataires et les utilisateurs du bâtiment. Voir les outils d’analyse des parties prenantes au chapitre 5.2 – Gestion des parties prenantes pour un supplément d’information.

Communications internes

Les communications internes sont celles qui se font à l’intérieur du bureau.

Patrons

Une bonne communication entre les patrons est essentielle au bon fonctionnement d’un bureau. Les associés d’une firme d’architecture sont généralement des individus aux forces complémentaires qui peuvent avoir des façons différentes de percevoir une même situation, ce qui rend encore plus importantes les bonnes communications.

Dans un article paru en 1982 dans le Professional Services Management Journal, Marty Grothe et Peter Wylie donnent les conseils suivants, qui sont de nature à aider les patrons à communiquer efficacement entre eux :

accepter que ses associés aient le droit d’être différents; ne pas essayer de les rendre semblables à soi;

être disposé à prendre régulièrement le temps de discuter ouvertement de sa relation avec eux;

être capable d’écouter le point de vue de l’autre, en particulier quand un problème a surgi;

assumer sa part de responsabilité s’il y a des difficultés dans la relation, plutôt que d’en rejeter tout le blâme sur les autres;

être disposé à chercher des solutions acceptables pour tous plutôt que d’essayer d’imposer son point de vue.

Personnel

Le personnel d’une firme d’architecture constitue sa ressource la plus précieuse. Les employés représentent la firme dans leurs communications avec les clients, les entrepreneurs et le public. Leurs aptitudes pour la communication dépendent dans une certaine mesure de la culture et des objectifs de la firme.

Les conseils suivants peuvent aider la firme à développer les aptitudes de son personnel pour la communication :

- insister sur l’importance des bonnes communications et donner l’exemple;

- faire régulièrement des présentations internes du projet devant des employés reconnus pour leur sens critique;

- discuter franchement des problèmes de la firme;

- être à l’écoute des préoccupations du personnel et adopter les suggestions valables;

- être clair et direct dans les évaluations de performance;

- utiliser les notes de service uniquement pour les informations d’ordre général; préférer le contact direct.

Voir le chapitre 3.6 – Ressources humaines.

Moyens de communication

Les paragraphes qui suivent décrivent brièvement certains moyens de communication.

Réunions

Une rencontre en personne aide souvent à résoudre un problème. La planification et l’organisation sont essentielles à l’efficacité de toute réunion.

Il est important de bien planifier les réunions et de bien les mener pour atteindre un objectif donné du projet.

Les réunions sont le lieu où s’échangent les communications relatives au projet.

Types de réunions :

- Réunions ordinaires – pour informer de l’avancement des projets et obtenir les commentaires du client, des professionnels et de l’entrepreneur;

- Réunions de prise de décision – pour résoudre des problèmes particuliers ou éviter des problèmes potentiels.

Voir l’Annexe A – Liste de contrôle : Planification d’une réunion, à la fin du chapitre.

Les précautions suivantes aident à obtenir le bon déroulement d’une réunion :

- faire circuler à l’avance l’ordre du jour accompagné d’informations générales, si possible;

- énoncer l’objectif de la réunion;

- commencer à l’heure fixée, ne pas attendre les retardataires et, si possible, ne pas résumer la discussion antérieure à leur arrivée;

- s’en tenir à l’ordre du jour et établir des limites de temps pour chaque point;

- rédiger un procès-verbal portant sur les points suivants :

- les informations nouvelles;

- les décisions prises (sans résumer la discussion);

- le suivi nécessaire (par qui et quand);

- reporter les points qui nécessitent une discussion plus approfondie;

- reporter les points qui requièrent plus d’information et confier cette recherche à quelqu’un.

Un formulaire de compte rendu de réunion est présenté au chapitre 3.11 – Modèles de formulaires pour la gestion d’une firme d’architecture.

Réunions par téléconférence ou vidéoconférence

Bien que les réunions en personne soient souvent le mode de communication préféré, les réunions par téléconférence et vidéoconférence (Skype, Zoom, Go-To-Meeting, WebEx, etc.) sont une solution pratique pour la gestion d’équipes virtuelles et permettent aux personnes travaillant dans des lieux différents de se « réunir » sans les coûts, le temps et les problèmes environnementaux liés aux déplacements. Ces réunions, si elles perdent les avantages de la communication en personne, offrent néanmoins des moyens rapides d’échanger des points de vue, de sonder un groupe lorsqu’un vote est nécessaire ou d’obtenir un consensus pour une décision.

Voici quelques conseils pour assurer la réussite des réunions par téléconférence ou vidéoconférence :

- organiser la conférence suffisamment à l’avance pour que toutes les parties soient disponibles;

- vérifier les fuseaux horaires des participants;

- nommer un président;

- fournir l’ordre du jour à l’avance;

- distribuer le procès-verbal le plus tôt possible.

Messagerie vocale et texto

La messagerie vocale et le texto – par lesquels on peut laisser (et prendre) des messages – peuvent être des outils de communication efficaces. Dans le cas des messages vocaux, veiller à :

- parler lentement et clairement, répéter les numéros de téléphone et indiquer le jour et l’heure;

- donner suffisamment de détails pour permettre au destinataire de fournir l’information demandée dans la boîte vocale de celui qui a laissé le message (cela contribue à réduire le chassé-croisé téléphonique);

- ne jamais enregistrer une conversation téléphonique sans en informer l’autre partie et obtenir son approbation;

- s’en tenir à des messages factuels et professionnels (les messages peuvent être archivés et, en cas de différend, pourraient peut-être servir comme éléments de preuve);

- indiquer quand et comment on peut vous joindre (téléphone cellulaire, numéro personnel ou autre numéro au bureau).

Appareils mobiles et applications

Les technologies de communication avancées et en constante évolution permettent de gagner du temps, ce qui profite aux processus de conception et de construction. Les architectes peuvent communiquer avec les chefs de chantier ou tout autre membre de l’équipe qui dispose également d’appareils mobiles pour éviter les retards dans les projets.

Grâce à leurs applications faciles à utiliser, les appareils mobiles permettent aux architectes et aux membres de l’équipe :

- d’accéder à des informations importantes sur le projet lorsqu’ils sont au bureau ou sur le chantier, de les documenter, de les partager et de les modifier;

- de fixer des rendez-vous et des réunions et de les inscrire à l’agenda;

- de communiquer des messages urgents.

Médias électroniques

Le courrier électronique, l’Intranet à l’intérieur d’une entreprise, l’Internet et les réseaux locaux sont les modes de communication les plus utilisés dans les firmes d’architecture. Il est important que le bureau conserve des dossiers permanents des courriels échangés pour chaque projet. Le mauvais usage des courriels risque d’exposer le bureau d’architectes à une plus grande responsabilité.

La numérisation des documents pour les joindre à un courriel est la façon la plus économique de transmettre un document d’un endroit à un autre.

Le courriel est maintenant d’utilisation courante et il est plus qu’un outil de « conversation ». Avant d’envoyer un courriel, demandez-vous si le message conviendrait s’il était tapé sur le papier officiel du bureau et posté au client ou s’il était transmis en personne. Il est important que les bureaux établissent des politiques et procédures pour ce mode de communications, car le courriel est plus qu’un document écrit, il projette l’image du bureau.

Les sites Web propres à un projet, souvent appelés « portails de projets » auxquels les ingénieurs, les entrepreneurs et les clients peuvent avoir accès, sont très courants et deviennent des outils de gestion de projet et des sources d’information exhaustives sur un projet. Toute la documentation du projet, y compris des photos de l’emplacement et des vidéos des travaux, peut être visionnée sur ces sites Web.

Transfert de fichiers électroniques

Les documents de conception et de construction sont généralement transférés par voie électronique, souvent à l’aide d’une URL particulière (localisateur de ressources uniformes), comme un site Web ou un site FTP (protocole de transfert de fichiers). Il est également possible de distribuer les documents d’appel d’offres par voie électronique, sans les imprimer.

Les entrepreneurs peuvent utiliser les fichiers électroniques comme bases pour leurs calculs de quantités. Nombre de municipalités et d’associations de construction acceptent la transmission électronique des documents. Les demandes de permis de construire peuvent circuler électroniquement entre les divers services d’une municipalité. On estime que cette façon de procéder améliore la transmission de l’information et accélère le traitement des demandes. Les documents peuvent aussi être transmis directement au chantier.

Il reste cependant nombre de questions à régler, comme :

- le respect du droit d’auteur (les documents électroniques sont très faciles à copier);

- l’augmentation des risques liés à la responsabilité professionnelle, en raison de modifications imperceptibles apportées aux documents électroniques;

- l’application des sceaux et signatures professionnels;

- l’assurance que les fichiers électroniques pourront être lus dans le futur.

[Note : Bien qu’il soit généralement admis que les supports électroniques peuvent se détériorer avec le temps, personne ne connaît avec certitude la rapidité ou la nature de la détérioration possible.]

Messagerie

Une compagnie de messagerie peut effectuer une livraison en aussi peu de temps que celui qui est nécessaire pour se déplacer du bureau de l’architecte à la destination finale. Comme pour les autres moyens de communication, la planification permet d’économiser : moins la livraison est urgente, moins le coût en est élevé.

Les architectes utilisent normalement les services de messagerie lorsqu’il est essentiel que des documents tels que des offres de service, des contrats, des instructions d’ordre juridique, etc., atteignent leur destination pour une heure précise. Il est important de vérifier si la compagnie garantit la livraison et détient une assurance qui couvre les documents ou objets perdus. Le service de messagerie doit également posséder la technologie qui permet de confirmer que la livraison a été effectuée, à qui et à quelle heure.

Télécopie

Les télécopieurs sont de plus en plus rares dans l’industrie de la conception et de la construction et bien des bureaux ont abandonné ce moyen de communication. Toutefois, certaines raisons justifient l’utilisation du télécopieur, notamment :

- l’envoi de documents juridiques sur lesquels des signatures originales sont requises;

- la transmission de documents sécurisés point par point;

- la confidentialité de l’information.

On peut économiser du papier en omettant le bordereau de transmission pour les lettres qui sont déjà adressées au destinataire.

Poste

Bien qu’il soit plus lent qu’un service de messagerie, le service de base de Postes Canada demeure le moyen le plus économique d’envoyer des documents. Tout n’est pas urgent et, avec une bonne planification, on peut réduire le recours aux services de messagerie. On peut expédier des documents confidentiels par la poste. Au besoin, l’envoi peut être recommandé. Postes Canada offre également des services de livraison préférentielle qui garantissent une livraison plus rapide que celle assurée par le service postal ordinaire.

Communications de l’avenir

MDB, données massives et Internet des objets

L’avenir des communications consiste à connecter des systèmes autonomes en utilisant de nouvelles technologies, telles que la modélisation des données du bâtiment (MDB) et le partage en temps réel entre l’architecte, le client, l’entrepreneur et l’équipe d’exploitation des installations. Par exemple, le MasterFormat (Répertoire normatif) est le format de devis le plus utilisé et est intégré dans la plupart des logiciels de MDB. La MDB permettra automatiquement à l’architecte de savoir quelles sections du devis sont nécessaires pour le manuel du projet. Les devis du projet peuvent également être liés aux dessins du projet. Aujourd’hui, les données massives et l’Internet des objets sont utilisés dans la gestion des actifs des bâtiments. À l’avenir, les données massives et l’Internet des objets amélioreront le processus de communication de la conception et de la construction.

Voir l’article de Becky Holten intitulé « How Technology Is Changing the Construction Industry. »

Références

ANGELL, David, and Brent Heslop. The Elements of E-mail Style, Don Mills, ON, Addison-Wesley Publishing, 1994.

BC BUILDING PROJECTS COMMITTEE. Management of Building Projects: A practice manual for all lead roles from project concept to completion, 1st Edition, Vancouver, BC, BC Building Projects Committee, 2004.

BORCHERDING, John D. “Improving Construction Communications.” Project Management Institute. http://www.pmi.org/learning/library/improving-construction-communications-behavioral-science-1748, consulté le 9 octobre 2020

CHENG, E.W.L., H. Li, P.E.D. Love, and Z. Irani. “Network communication in the construction industry.” Corporate Communications: An International Journal. 2001, Vol. 6 No. 2, pp. 61-70. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563280110390314, consulté le 9 octobre 2020.

DAINTY, Andrew, David Moore, and Michael Murray. Communication in Construction, Theory and Practice, UK, Taylor and Francis, 2006.

DICKINSON, John, and Paul Woodard, eds. Manuel de pratique canadien pour la MDB, buildingSMART Canada, 2016.

EMMITT, Stephen, and Christopher A. Gorse. Construction Communication, Oxford, UK, Wiley-Blackwell, 2003.

FLESNER, Neal. “Why Is Communication Important on Construction Projects?” Ventura Consulting Group, March 2017. https://venturaconsulting.com/why-is-communication-important-on-construction-projects, consulté le 9 octobre 2020

GOUVERNEMENT DU CANADA, ministère de la Justice. Le Manuel relatif au règlement des conflits. (2006), https://www.justice.gc.ca/fra/pr-rp/sjc-csj/sprd-dprs/res/mrrc-drrg/index.html, consulté le 9 octobre 2020.

GREUSEL, David. « Communicating with Clients. » The Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice, Fourteenth Edition. American Institute of Architects, Joseph A. Demkin, ed. John Wiley & Sons, 2008.

HOEZEN, M.E.L., I.M.M.J. Reymen, and G.P.M.R. Dewulf. The Problem of Communication in Construction. University of Twente, 2011. https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/the-problem-of-communication-in-construction, consulté le 9 octobre 2020.

HOLTEN, Becky. “How Technology Is Changing the Construction Industry.” Building Enclosure, December 20, 2018. https://www.buildingenclosureonline.com/blogs/14-the-be-blog/post/87981-how-technology-is-changing-the-construction-industry, consulté le 9 octobre 2020.

KLIEM, Ralph L. Effective Communications for Project Management, New York, Auerbach Publications, 2007.

PROJECT MANAGEMENT INSTITUTE. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Sixth Edition, Newtown Square, PA, Project Management Institute, 2017.

SIEVERT, R.W. “Communication: An Important Construction Tool.” Project Management Journal, 17(5), pp. 77-82, 1986.

STONE, David A. Mastering the Business of Architecture. Toronto, ON, Ontario Association of Architects, 1999.

VERMA, Vijay K. The Human Aspects of Project Management, Volume Two: Human Resources Skills for the Project Manager, Newtown Square, PA, Project Management Institute, 1996.

WANG, Zachary. Human Factors in Project Management: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques for Inspiring Teamwork and Motivation, San Francisco, CA, Jossey-Boss, 2007.