Définitions

Addenda : Modification apportée aux documents d’appel d’offres (généralement aux dessins ou au devis descriptif) pendant la période d’appel d’offres et avant la conclusion du contrat.

Caution : Partie (société de cautionnement) qui émet un cautionnement garantissant qu’une autre personne (l’entrepreneur, dans le cas présent) remplira ses obligations contractuelles dans les limites financières et temporelles indiquées dans le cautionnement.

Cautionnement : Garantie financière relative à l’exécution d’une obligation; généralement un document écrit soutenu par une garantie mobilière.

Garantie (guarantee) : Une promesse de répondre du paiement d’une dette ou de l’exécution d’une obligation si la personne responsable en première instance n’effectue pas le paiement ou n’exécute pas l’obligation (pour être exécutoire, elle doit être attestée par écrit).

Garantie (warranty) : Une déclaration de fait ou de qualité sur laquelle peut se fier une autre partie, comportant une promesse implicite ou explicite de réparer tout manquement.

Préachat : Achat de matériaux, d’équipement ou de services par le maître de l’ouvrage avant l’attribution du contrat principal.

Préappel d’offres : Procédure par laquelle le maître de l’ouvrage procède à un appel d’offres partiel avant l’appel d’offres principal. Dans ce cas, il donne instruction aux soumissionnaires d’inclure le montant ainsi obtenu dans leur soumission.

Présélection : Procédure par laquelle un maître de l’ouvrage qualifie et choisit un fabricant ou un fournisseur avant l’appel d’offres ou avant l’attribution du contrat.

Soumission de base : Le montant forfaitaire, sans aucun rajustement en raison de prix pour variantes ou de substitutions ou autres, pour lequel le soumissionnaire offre d’exécuter les travaux prévus dans les documents d’appel d’offres.

Soumission : Offre présentée en réponse à un appel d’offres; estimation de prix ou de délai, présentée en réponse à un appel d’offres; l’offre est valide aussi longtemps que la période d’acceptation n’est pas terminée.

Préambule

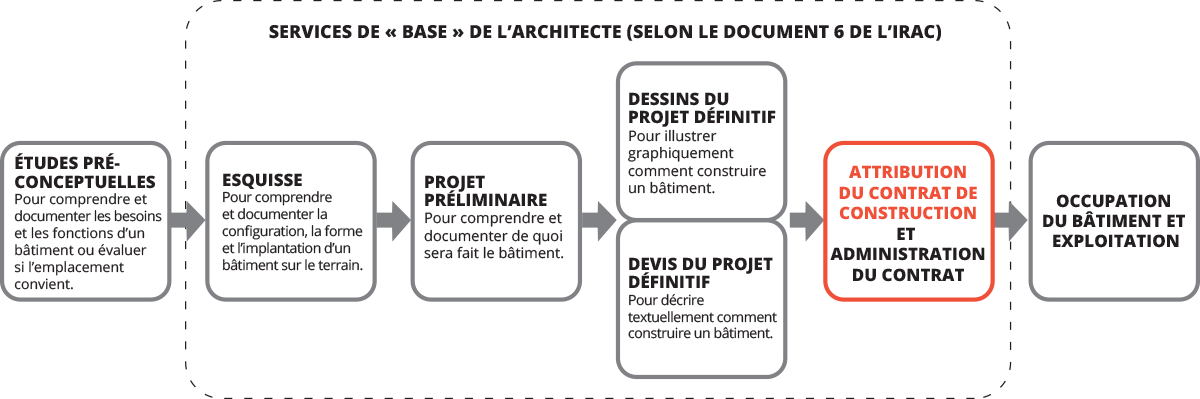

Il existe bien des méthodes pour former les équipes de conception et de construction dans un programme de conception-construction et pour choisir le constructeur. Le présent chapitre traite principalement du choix de l’entrepreneur de construction selon le mode conception-offres-construction qui se caractérise comme suit :

- l’architecte est engagé directement par le client pour gérer le projet de conception, superviser l’attribution du contrat de construction et en assurer ensuite l’administration;

- les ingénieurs peuvent être engagés soit par l’architecte, soit par le client;

- après l’achèvement des documents de construction par l’équipe de conception, l’entrepreneur est choisi à la suite d’un appel d’offres;

- les entrepreneurs spécialisés et les sous-traitants sont engagés par l’entrepreneur.

Le chapitre ne traite pas des situations dans lesquelles l’architecte est engagé par un design-constructeur et dans lesquelles l’attribution du contrat de construction précède la conception du bâtiment. Il ne traite pas des partenariats public-privé dans lesquels des équipes de promoteurs composées de financiers, de concepteurs, de constructeurs et d’exploitants forment une seule entité pour concourir pour un projet par un processus complexe d’entrevues, d’itérations conceptuelles et d’analyse détaillée des coûts d’investissement et d’exploitation. Enfin, il ne traite pas non plus des variantes de la réalisation de projet intégrée (RPI) dans lesquelles l’équipe de conception et l’équipe de construction sont toutes deux retenues par le client au début du projet ou peu après.

Le mode de gérance de construction n’est pas incompatible avec le mode conception-offres-construction; toutefois, il y a quelques différences ayant trait notamment à l’ajout d’une expertise en constructibilité et en estimation des coûts pendant la conception; à une compression du calendrier de réalisation du projet; et à de multiples dossiers d’appel d’offres basés sur des jeux de dessins partiels spécifiques à un corps de métier donné. Voir le chapitre 4.1 – Modes de réalisation des programmes de conception-construction pour un supplément d’information à ce sujet.

Introduction

L’appel d’offres et l’attribution du contrat de construction doivent suivre des règles strictes. Tout écart par rapport aux pratiques d’appels d’offres acceptées peut entraîner des violations de la common law canadienne en matière d’appels d’offres et de soumissions. L’architecte est invité à consulter l’ouvrage de Paul Sandori et William Pigott intitulé Bidding and Tendering: What Is the Law? 5th Edition, pour une explication détaillée des procédures et de la jurisprudence concernant l’approche exclusivement canadienne en matière d’appels d’offres et de soumissions.

L’architecte ne doit jamais oublier que les entrepreneurs en construction, les sous-traitants et les fournisseurs de produits investissent des ressources importantes dans la préparation d’une soumission. Il est donc essentiel qu’il assure un processus équitable et transparent pour tous les soumissionnaires afin de maintenir de bonnes relations professionnelles et d’être respecté au sein de l’industrie.

Ce chapitre porte sur les divers modes de sélection des entrepreneurs et d’attribution des contrats de construction. Voir également le CCDC 23 – Guide des appels d’offres et de l’attribution des contrats de construction pour un supplément d’information à ce sujet.

En bref, la sélection d’un entrepreneur en construction comporte les étapes suivantes :

- planification du mode d’attribution du contrat;

- préqualification des soumissionnaires;

- appel d’offres;

- évaluation des soumissions;

- attribution du contrat de construction.

Planification du mode d’attribution du contrat de construction dans le cadre d’un programme de conception-construction

Le client, avec l’aide de l’architecte, choisit l’entrepreneur général en ayant recours à l’une des méthodes suivantes :

- appel d’offres public;

- appel d’offres sur invitation;

- sélection directe.

L’Annexe A – Services de la Formule canadienne normalisée de contrat pour les services de l’architecte du Document Six 2018 de l’IRAC prévoit notamment les deux services suivants rendus par l’architecte : « Aider le client pour la préqualification des soumissionnaires » et « Aider le client à préparer l’appel d’offres ». Cette tâche peut être considérable; mais si le client est expert dans le domaine, elle peut se limiter à fournir de l’information et à donner des avis.

La planification de la procédure de sélection de l’entrepreneur en construction doit commencer dès le début du projet afin d’éviter les reprises dans le travail et les retards dans le calendrier. Le fait de passer d’un contrat à prix forfaitaire avec un seul entrepreneur à la gérance de construction vers la fin de la phase de production des documents peut entraîner d’importants travaux supplémentaires et des retards dans le calendrier de réalisation du projet.

L’approche doit tenir compte des éléments suivants :

- l’équilibre entre le coût et le prix, les contraintes du calendrier et la qualité;

- la complexité du projet ou son caractère novateur qui nécessitent son exécution par des entrepreneurs ayant des compétences spéciales;

- l’incertitude et le risque du projet.

Lors de la mise en marche du projet, l’architecte et son client doivent choisir :

- le mode de réalisation du projet de conception-construction;

- le type de contrat de construction;

- le mode d’attribution du contrat.

Ces décisions ont des répercussions sur :

- l’étendue des services et des honoraires de l’architecte;

- le calendrier de réalisation;

- la préparation des documents de construction et des documents d’appel d’offres;

- l’appel d’offres.

Voir le chapitre 4.1 – Modes de réalisation des programmes de conception-construction pour une comparaison des trois modes les plus courants.

Par exemple, un contrat à forfait avec appel d’offres unique est beaucoup plus simple à administrer qu’un processus contractuel comportant plusieurs appels d’offres à diverses étapes du projet, comme c’est le cas en gérance de construction.

Pour que tous les entrepreneurs soumissionnent sur un produit fini comparable, l’appel d’offres devant mener à la conclusion d’un contrat à forfait avec un entrepreneur général n’a lieu qu’une fois tous les documents de construction (y compris les dessins et les devis) achevés. Tous les critères de sélection du soumissionnaire qui obtiendra le contrat doivent être inclus dans les documents d’appel d’offres.

Appel d’offres

Les trois types d’appels d’offres concurrentiels examinés dans le présent chapitre sont :

- l’appel d’offres concurrentiel ou appel d’offres public;

- l’appel d’offres sur invitation;

- la sélection directe ou le recours à un fournisseur exclusif.

La tenue de l’appel d’offres, qu’il soit ouvert ou sur invitation, comprend généralement les étapes suivantes :

- informer les soumissionnaires éventuels de la possibilité de soumissionner pour le contrat de construction par le biais d’annonces publiques ou d’un contact direct;

- publier les documents d’appel d’offres à l’intention des soumissionnaires;

- organiser une séance d’information à l’intention des soumissionnaires au cours de laquelle ils ont tous l’occasion de poser des questions et, dans le cas de bâtiments existants, de visiter les lieux;

- répondre aux demandes de renseignements;

- recevoir et évaluer les offres;

- négocier les conditions du contrat en suspens;

- attribuer le contrat de construction.

Appel d’offres concurrentiel (ou appel d’offres public)

Avec l’appel d’offres public, les soumissionnaires ne sont généralement pas soumis à une épreuve de « qualification », ce qui fait que le client n’est pas assuré de leur capacité à exécuter les travaux. L’entrepreneur peut être sélectionné sur la base de son prix uniquement. Ce type d’appel d’offres est fréquemment utilisé lorsque le projet implique des fonds publics.

Habituellement, l’avis d’appel d’offres est publié sur divers sites Web ou services d’appel d’offres électroniques, dans des quotidiens ou dans des publications spécialisées. Cet avis indique :

- le nom et l’emplacement du projet;

- le nom du client et de l’architecte;

- les dimensions du projet et le type de projet;

- la date de clôture de l’appel d’offres;

- le mode d’obtention des documents d’appel d’offres;

- les exigences en matière de cautionnement de soumission (cautionnement ou dépôt);

- la date de la séance d’information (s’il y en a une) et l’endroit où elle aura lieu;

- la date du début des travaux et celle de leur achèvement (s’il y a lieu);

- la formule de contrat utilisée.

L’avis permet aux entrepreneurs de décider s’ils désirent saisir cette occasion.

Appel d’offres sur invitation

L’appel d’offres sur invitation permet au client de choisir des entrepreneurs avec lesquels l’architecte ou le client ont eu de bonnes expériences. Il permet aussi au client et à l’architecte de choisir les entrepreneurs à inviter par voie de préqualification. Dans ces cas-là, les architectes aident souvent leurs clients à évaluer les capacités et les antécédents des entrepreneurs généraux et des entrepreneurs spécialisés susceptibles d’être invités à soumissionner.

Dans un processus de préqualification, le client, avec l’aide de l’architecte et des ingénieurs, recueille de l’information sur un entrepreneur pour déterminer s’il a la capacité et l’expérience requises pour entreprendre le projet. Les documents de préqualification peuvent comprendre :

- de l’information sur l’entreprise, y compris sa structure juridique, la date de sa création, sa capacité exprimée sous forme de revenu brut annuel;

- les curriculum vitae des principaux employés qui travailleront au projet;

- la capacité d’exécuter les travaux démontrée par la construction de projets semblables;

- la méthode utilisée pour gérer les projets de construction;

- les dossiers liés à la sécurité (déclaration relative aux réclamations d’assurance ou aux réclamations pour blessures);

- d’autres caractéristiques de l’entreprise, comme ses politiques en matière d’environnement, de diversité à l’emploi, de responsabilité sociale, etc.

En début de processus, une étape de préqualification aide à éliminer les candidats qui n’ont pas les moyens financiers, l’expérience et les ressources humaines nécessaires à l’exécution du projet. Voir le CCDC 11 – Déclaration de qualification d’un entrepreneur. Une fois qualifiés, les soumissionnaires peuvent généralement être considérés comme étant de compétence égale, et le contrat peut être attribué au plus bas soumissionnaire.

La qualification préalable peut comporter des pièges et les architectes voudront peut-être établir des critères clairs et transparents et les utiliser au moment de sélectionner ou d’éliminer des entrepreneurs, pour ne pas être accusés de favoritisme.

L’appel d’offres sur invitation est généralement utilisé pour les types de projets suivants :

- projets de clients privés qui préfèrent choisir parmi un groupe d’entrepreneurs qui, à leurs yeux, ont fait leurs preuves;

- projets spécialisés qui exigent une expertise particulière;

- petits projets qui n’attireraient peut-être pas l’attention des entrepreneurs si on procédait par appel d’offres public.

Sélection directe

Il est toujours possible pour un client de négocier un contrat avec un seul entrepreneur, surtout s’il s’agit d’un entrepreneur avec qui des liens de confiance se sont noués avec le temps. Le client et l’architecte (possiblement avec l’aide d’un estimateur-conseil) doivent s’assurer que des estimations détaillées du coût de construction ont été préparées pour servir de base aux négociations. Au cours des négociations, l’entrepreneur peut proposer des modifications ou des solutions de rechange qui doivent être évaluées et acceptées.

Les contrats négociés sont basés sur la confiance mutuelle et la divulgation complète de toutes les estimations et les soumissions. La sélection directe et la négociation mènent souvent aux types suivants de contrats de construction :

- à forfait, comme le CCDC 2 – Contrat à forfait;

- à prix coûtant majoré ou avec un prix maximum garanti, comme le CCDC 3 – Contrat à prix coûtant majoré;

- gérance de construction.

Contrats négociés

Le client peut être amené à s’engager dans la négociation d’un contrat dans les situations suivantes :

- il a établi de bonnes relations avec un ou plusieurs constructeurs;

- les risques sont trop élevés pour obtenir un prix ferme acceptable;

- il effectue sa sélection en se basant principalement sur les qualifications;

- ses politiques permettent de tenir compte des qualifications dans la sélection de l’entrepreneur, le prix devant être négocié.

Les contrats négociés sont surtout utilisés en cas d’urgence, lorsque le temps est compté ou lorsqu’un maître de l’ouvrage apprécie les avantages de relations établies à long terme. Un client peut utiliser à la fois une approche négociée et une approche par appel d’offres dans un même projet.

Cautionnements

Dans l’industrie de la construction, un cautionnement est un instrument qui permet à un entrepreneur de fournir à un client la garantie d’une société de cautionnement appelée « caution ». La garantie assure que l’entrepreneur s’acquittera de manière satisfaisante de ses obligations contractuelles. Selon le CCDC 22 – Guide d’utilisation des cautionnements de construction, les cautionnements sont un moyen utile d’assurer l’exécution responsable d’un contrat et la sécurité financière et c’est pourquoi ils sont souvent une exigence essentielle de l’attribution des contrats de construction. Un cautionnement n’est pas une police d’assurance; c’est plutôt l’engagement que prend un tiers d’indemniser le maître de l’ouvrage contre la perte qui découlerait de l’incapacité de l’entrepreneur de remplir ses obligations contractuelles.

L’architecte doit bien connaître les divers types de cautionnements et leur usage. Voir le CCDC 22 – Guide d’utilisation des cautionnements de construction pour un supplément d’information à ce sujet.

Pendant la préparation des documents de l’appel d’offres, l’architecte doit chercher conseil auprès d’un spécialiste de l’assurance dans la construction avant de conseiller le client sur le type et le montant des cautionnements appropriés pour le projet. Dans les contrats de construction, trois types de cautionnement sont importants :

- le cautionnement de soumission;

- le cautionnement d’exécution;

- le cautionnement de paiement de la main-d’œuvre et des matériaux.

Cautionnement de soumission

Le cautionnement de soumission garantit au maître de l’ouvrage que si la soumission est acceptée dans le délai prévu, l’entrepreneur conclura un contrat avec lui. Si l’entrepreneur ne le fait pas, la caution s’engage à payer au maître de l’ouvrage, jusqu’à concurrence du montant du cautionnement, la différence entre le prix de la soumission de l’entrepreneur et le montant pour lequel le maître de l’ouvrage conclura un contrat avec un autre entrepreneur. La valeur du cautionnement se situe généralement entre 5 % et 10 % du coût de construction estimé; dans le cas de très grands projets, 2,5 % est considéré comme un pourcentage approprié.

L’architecte voudra peut-être demander également d’autres formes de garantie de soumission :

- un chèque certifié;

- une lettre de crédit irrévocable d’une institution financière;

- des garanties négociables (dans de rares situations).

Il est fréquent que des petits entrepreneurs, par ailleurs qualifiés pour réaliser des projets de faible importance ou particuliers, ne disposent pas de moyens financiers suffisants pour obtenir un cautionnement de soumission. En pareil cas, il y a lieu d’envisager d’autres formes de garantie de soumission.

Il est recommandé d’utiliser le CCDC 220 – Cautionnement de soumission si l’on choisit le cautionnement de soumission.

Cautionnement d’exécution

Le cautionnement d’exécution a pour fonction d’indemniser le maître de l’ouvrage en cas de défaillance (banqueroute, insolvabilité) de l’entrepreneur. Le cautionnement couvre alors le coût de l’achèvement des travaux, ainsi que d’autres coûts dont la caution assume la responsabilité, jusqu’à concurrence du montant total du cautionnement. Ce montant est souvent basé sur un pourcentage du montant du contrat, par exemple, 50 % ou 100 %.

La société qui a fourni un cautionnement de soumission ne s’est pas engagée à fournir le cautionnement d’exécution; il est donc prudent d’obtenir de celle-ci un engagement distinct à fournir un cautionnement d’exécution si l’entrepreneur obtient le contrat. Cet engagement prend généralement la forme d’une lettre signée par la société de cautionnement et que l’on appelle parfois « Consentement de garantie », ou « Entente de garantie » ou « Lettre de cautionnement ».

Le cautionnement d’exécution ne couvre pas les réclamations relatives au paiement de la main-d’œuvre et aux matériaux.

Il est recommandé d’utiliser le CCDC 221 – Cautionnement d’exécution pour les cautionnements d’exécution; toutefois, bien des sociétés de cautionnement ont leur propre type de documents à cet égard.

Cautionnement de paiement de la main-d’œuvre et des matériaux

Un cautionnement de paiement de la main-d’œuvre et des matériaux garantit que les sous-traitants et fournisseurs de l’entrepreneur seront payés pour la main-d’œuvre et les matériaux fournis à l’entrepreneur pour le projet identifié dans le cautionnement. Il est recommandé d’utiliser le CCDC 222 – Cautionnement de paiement de la main-d’œuvre et des matériaux; toutefois, bien des sociétés de cautionnement ont leur propre type de documents à cet égard.

Voir le CCDC 22 – Guide d’utilisation des cautionnements de construction pour un supplément d’information.

Préparation du dossier d’appel d’offres

Le dossier remis aux soumissionnaires pour qu’ils puissent préparer leurs soumissions est constitué des éléments énumérés à l’Annexe A – Liste de contrôle – Le dossier d’appel d’offres : une liste des informations requises à la fin du présent chapitre.

Dans la préparation du dossier d’appel d’offres, l’architecte devrait utiliser le CCDC 23 – Guide des appels d’offres et de l’attribution des contrats de construction comme référence. Il doit éviter de multiplier les conditions générales supplémentaires dans la préparation et l’utilisation des documents du CCDC. Le CCDC n’approuvera aucune condition générale supplémentaire; la modification des contrats du CCDC par ajout, suppression ou révision doit être réduite au minimum et n’être envisagée qu’après un examen approfondi. Les utilisateurs des documents du CCDC sont d’ailleurs avertis d’éviter les révisions arbitraires qui pourraient affaiblir les dispositions des documents et créer de sérieux problèmes.

L’ajout de conditions supplémentaires à une formule normalisée de contrat devrait se limiter à garantir que le contrat est en adéquation avec le contexte du projet. Par exemple, un projet peut exiger que l’entrepreneur et les sous-traitants obtiennent une cote de sécurité élevée ou assument la responsabilité de mesures de sécurité allant au-delà des protocoles habituels de sécurité du chantier. Les conditions supplémentaires ne doivent pas être utilisées pour modifier la nature de la relation entre le maître de l’ouvrage et l’entrepreneur ou transférer un risque excessif ou ingérable d’une partie à l’autre.

Dans certaines circonstances, il peut être nécessaire de préparer des dossiers d’appel d’offres spéciaux et de fournir de la documentation additionnelle. L’architecte doit fournir aux soumissionnaires toute l’information nécessaire sur la présélection d’un fabricant ou d’un fournisseur, le préachat de matériaux, ou les responsabilités que le soumissionnaire choisi doit assumer. (Voir la section « Définitions » au début du chapitre.)

Voici quelques exemples de situations de ce genre :

- le maître de l’ouvrage a des exigences spéciales en matière d’assurance et d’indemnisation;

- le maître de l’ouvrage, pour accélérer la réalisation du projet, fait construire à l’avance une partie de l’ouvrage (les fondations, par exemple);

- le maître de l’ouvrage achète à l’avance des matériaux ou des produits qui seront incorporés à l’ouvrage;

- le maître de l’ouvrage conclut des contrats préalables pour l’acier de charpente ou certains éléments mécaniques ou électriques;

- le maître de l’ouvrage a acheté directement certaines pièces d’équipement en vue de leur installation future dans le bâtiment (cette situation est fréquente pour de l’équipement hospitalier, qui sera mis en place par un sous-traitant de l’entrepreneur général).

Voir aussi le chapitre 6.4 – Dossier définitif, Annexe E – Devis descriptif.

Clauses de privilège

Dans le passé, il était habituel pour les maîtres d’ouvrage et les architectes d’exercer un certain contrôle sur le processus d’appel d’offres en insérant dans le dossier d’appel d’offres une « clause de privilège » qui pouvait se lire comme suit :

« Le client ne s’engage à accepter ni la plus basse ni aucune autre des soumissions ».

Une telle clause n’est plus appropriée. On croyait qu’elle permettait aux maîtres d’ouvrage d’accorder le contrat à une personne physique ou morale autre que le plus bas soumissionnaire. Une décision rendue par la Cour suprême du Canada en avril 1999 fournit une interprétation définitive de cette partie de la législation sur les appels d’offres. Le maître de l’ouvrage est censé accorder le contrat conformément aux conditions de l’appel d’offres et ne doit pas favoriser de façon injuste un des soumissionnaires.

Le fait d’accepter une soumission non conforme est considéré comme un manquement à l’obligation de traiter équitablement tous les autres soumissionnaires. Une clause de privilège ne permet pas au maître de l’ouvrage d’accepter une soumission non conforme.

Les architectes sont invités à bien examiner l’article 2.0 Principes de la loi sur les appels d’offres du CCDC 23 – Guide des appels d’offres et de l’attribution des contrats de construction.

Lors de la préparation des documents d’appel d’offres, il est essentiel d’inclure les éléments suivants dans les Instructions aux soumissionnaires :

- les conditions de conformité d’une soumission;

- s’il est possible ou non de retirer une soumission et si oui, dans quelles circonstances;

- s’il est permis de négocier avec l’un des soumissionnaires avant l’attribution du contrat, et dans quelles circonstances;

- tous les critères de sélection du soumissionnaire à qui sera attribué le contrat.

Il serait sage, au moment de préparer les documents d’appel d’offres, de demander conseil à son ordre d’architectes provincial ou territorial ou à un avocat spécialisé dans la construction.

Distribution des documents d’appel d’offres

Généralement, l’avis d’appel d’offres indique l’endroit où les entrepreneurs peuvent se procurer les documents d’appel d’offres et à quelles conditions. L’architecte peut se charger de l’administration et de la distribution des dossiers d’appel d’offres; par contre, le client expérimenté ou averti s’en chargera souvent lui-même.

Nombre de jeux de documents d’appel d’offres

Les clients, les ingénieurs et autres conseils, les entrepreneurs et les sous-traitants ont tous intérêt à ce que les dessins et les devis descriptifs soient facilement accessibles pendant la période de l’appel d’offres. En favorisant l’accès électronique et en imprimant suffisamment de jeux de documents, on s’assure qu’un maximum d’entrepreneurs spécialisés et de fournisseurs auront l’occasion d’en prendre connaissance et de présenter des prix concurrentiels.

Au moment de déterminer les modalités de distribution électronique des documents d’appels d’offres et le nombre de jeux de documents à imprimer, l’architecte doit tenir compte des facteurs suivants :

- les besoins du client, de l’architecte et des ingénieurs;

- les besoins des autorités compétentes;

- le type et le nombre de services d’appels d’offres électroniques, comme Biddingo.com, Merx.com, le site Web d’approvisionnement du gouvernement fédéral, achatsetventes.gc.ca ou bidsandtenders.ca;

- les jeux pour les salles de plans des associations de la construction;

- la taille et la complexité des projets (le nombre d’entrepreneurs spécialisés);

- le nombre prévu d’entrepreneurs et de sous-traitants soumissionnaires;

- la quantité nécessaire à l’exécution des travaux.

Il est également important de n’émettre que des jeux complets, et non partiels, de documents d’appels d’offres.

Le contrat client-architecte ne doit pas stipuler le nombre de jeux inclus dans les honoraires.

L’impression des dessins et des devis est une dépense remboursable. Si le client tient à inclure un nombre minimum de jeux dans les honoraires, l’architecte doit rajuster ceux-ci en conséquence. Les parties devraient également s’entendre sur le formatage, la diffusion et la distribution des données électroniques.

Il est important de contrôler la distribution des documents et des addendas. On trouvera une « Liste de distribution des documents d’appel d’offres » typique au chapitre 6.8 – Formulaires modèles pour la gestion du projet.

Dépôt de garantie

Les entrepreneurs obtiennent généralement les documents d’appel d’offres en fournissant un dépôt destiné à garantir le retour de ceux-ci. Le montant de ce dépôt est habituellement égal au coût d’impression d’un jeu complet de documents, plus des frais de manutention minimes. Ce dépôt est rendu si les documents retournés sont complets et en bon état. Les documents peuvent aussi être fournis à un entrepreneur général, un entrepreneur spécialisé, un fournisseur ou autre, au prix coûtant plus frais d’administration, sans aucune remise d’argent.

Associations de la construction et bureaux de dépôt des soumissions

L’accès à l’information est d’importance cruciale et la réussite de l’appel d’offres repose sur la facilité d’obtention de l’information. Pour un projet complexe ou de grande envergure, il faudra peut-être distribuer des jeux de documents additionnels ou recourir à un service d’appels d’offres électronique. On pourra aussi fournir des jeux complets de ces documents aux associations de la construction, surtout s’il s’agit de projets d’envergure faisant appel à un grand nombre de sous-traitants.

Un bureau de dépôt des soumissions est une installation administrée par l’association de construction locale et servant à la collecte et à l’enregistrement des soumissions des sous-traitants et des fournisseurs et à leur transmission aux entrepreneurs généraux. Généralement, ces soumissions pour les entrepreneurs généraux doivent être déposées dans un délai précis avant la date de clôture de l’appel d’offres. Le bureau de dépôt des soumissions peut confirmer les règles à cet égard. Voir le chapitre 2.1 – L’industrie de la construction pour une description sommaire du rôle des bureaux de dépôt des soumissions.

Addendas

Les entrepreneurs, les sous-traitants et les fabricants qui procèdent à une analyse détaillée des documents lors de la préparation de leurs soumissions peuvent constater des erreurs, des omissions ou des contradictions ou avoir besoin d’éclaircissements sur certains éléments.

L’architecte et les ingénieurs peuvent également découvrir des manques de cohérence ou des omissions, ou avoir approuvé d’autres produits comme étant des substituts acceptables. Par ailleurs, le client peut vouloir apporter des changements mineurs au projet. Lorsqu’on le questionne sur les documents, l’architecte doit être prudent s’il transmet une nouvelle information et répondre uniquement par écrit avec copie à tous les soumissionnaires ainsi qu’aux associations de la construction, au bureau de dépôt des soumissions, au client, aux ingénieurs et aux autorités compétentes.

Dans tous ces cas, l’architecte doit préparer des « addendas » qui modifient ou interprètent les documents d’appel d’offres. Ils comportent du texte et des dessins, ou du texte seulement. Chaque addenda doit être numéroté et daté, et être incorporé aux documents contractuels une fois le contrat conclu. Les addendas des ingénieurs doivent parvenir aux soumissionnaires par l’entremise de l’architecte; leur numérotation doit être intégrée à celle de l’architecte. La nouvelle information qu’ils constituent doit être énoncée avec une grande précision pour que les soumissionnaires puissent savoir exactement ce qui demeure et ce qui est ajouté, retranché ou modifié. Tous les soumissionnaires doivent établir leur soumission en se basant sur la même information.

L’architecte qui prépare un addenda facilite la tâche aux soumissionnaires et aux administrateurs de contrat s’il suit les procédures suivantes :

- indiquer le nom et le numéro du projet sur tous les addendas;

- indiquer la date de publication de chaque addenda;

- numéroter les addendas de façon consécutive;

- inscrire l’information dans un ordre logique (dans le même ordre que dans les dessins et devis);

- donner des instructions simples et claires, comme « supprimer : » et « ajouter : » et « modifier comme suit : »;

- indiquer sur toutes les pièces jointes leur relation avec l’addenda, en indiquant un numéro de dessin ou de détail, ainsi que le numéro de la section de devis suivi de l’article et du numéro de paragraphe;

- indiquer la référence à la pièce jointe.

Un exemple d’addenda est fourni au chapitre 6.8 – Formulaires modèles d’administration du projet.

Il faut éviter de publier des addendas plus tard que quatre jours ouvrables avant la clôture de l’appel d’offres. Tous les entrepreneurs doivent recevoir, en temps utile et par écrit, les mêmes informations. Si ce n’est pas possible, on doit envisager de reporter la date de clôture de l’appel d’offres.

Période d’appel d’offres et clôture de l’appel d’offres

S’il veut recevoir des prix compétitifs, le client doit laisser aux entrepreneurs le temps voulu pour étudier les documents et préparer une soumission. La durée optimale de l’appel d’offres varie selon les projets. Dans le cas d’un projet complexe ou de grande envergure faisant l’objet d’un « appel d’offres public », la durée de l’appel d’offres pourra être de quatre à six semaines; à l’opposé, un petit projet faisant l’objet d’un appel d’offres sur invitation peut n’exiger que deux semaines. Les conditions du marché peuvent se répercuter sur les soumissions; par exemple, si plusieurs appels d’offres sont en cours, il faudra peut-être prolonger la période d’appel d’offres.

Il n’est pas recommandé de recevoir les soumissions à plus d’un endroit. Il est de plus en plus courant que les soumissions soient reçues par voie électronique et les architectes sont invités à consulter l’article 7.8 du CCDC 23 – Guide des appels d’offres et de l’attribution des contrats de construction pour de l’information sur les principes qui s’appliquent à la réception des soumissions par voie électronique.

Il n’est pas recommandé de placer la clôture de l’appel d’offres un vendredi ou un lundi, ou immédiatement avant ou après un jour férié. L’heure la meilleure est le milieu ou la fin de l’après-midi. Il est important d’indiquer « avant » telle heure plutôt qu’« à » telle heure. On écrira, par exemple :

Les soumissions doivent être reçues avant 15 heures le jeudi 26 novembre 2020.

La personne qui reçoit les soumissions doit, au moment où elles arrivent, indiquer sur l’enveloppe l’heure et la date de réception, de même que ses initiales. Toute soumission reçue après l’heure prescrite doit être retournée au soumissionnaire sans être ouverte et accompagnée d’une note indiquant qu’elle est arrivée en retard. Aucun motif de retard (accident, embouteillage, etc.) ne peut être admis. Par contre, si une cause externe telle qu’une tempête de neige empêchait la majorité des soumissionnaires attendus de présenter une soumission, la clôture de l’appel d’offres pourrait être reportée, auquel cas les soumissions reçues seraient retournées à leurs expéditeurs sans avoir été ouvertes.

Idéalement, on ouvre les soumissions peu de temps après l’heure de clôture. Dans le cas de projets publics et de certains projets privés, on y procède en présence des soumissionnaires ou de leurs représentants. On ne dévoile que les éléments suivants :

- le nom de l’entrepreneur;

- le montant de la soumission de base;

- la présence du cautionnement de soumission ou d’une autre garantie, comme requis.

On ne fait pas mention des prix pour substituts ou des prix non sollicités. Les prix pour substituts exigent une analyse; les dévoiler en ce moment pourrait créer des malentendus.

Un formulaire intitulé « Sommaire des soumissions » est fourni au chapitre 6.8 – Formulaires modèles d’administration du projet. Ce document peut s’avérer fort utile au client et à l’architecte pendant la séance d’ouverture des soumissions.

Il peut arriver qu’un soumissionnaire avise l’architecte ou le client que sa soumission comporte une erreur importante, auquel cas on devrait lui permettre de se retirer sans pénalité. Cependant, le dépôt d’une soumission constitue un contrat entre le soumissionnaire et le maître de l’ouvrage, et ce contrat est exécutoire. Dans ces conditions, un soumissionnaire ne peut retirer sa soumission pendant la période d’irrévocabilité de celle-ci (habituellement la période indiquée dans le cautionnement de soumission). Le soumissionnaire qui retirerait sa soumission entraînerait la confiscation de la garantie ou du cautionnement de soumission. Il y a lieu en pareil cas de solliciter une opinion juridique. Le CCDC 23 prévoit que « si l’autorité qui lance l’appel d’offres se persuade qu’il existe une erreur indéniable et importante, elle ne devrait pas accepter la soumission et le soumissionnaire ne devrait pas être pénalisé, même si le maître de l’ouvrage peut avoir légalement le droit d’accepter la soumission ».

Si un seul soumissionnaire présente une soumission, l’architecte devrait conseiller au client d’envisager de retourner la soumission sans l’ouvrir ou de négocier avec le soumissionnaire.

Voir le CCDC 23 – Guide des appels d’offres et de l’attribution des contrats de construction pour un supplément d’information.

Analyse des soumissions

Dans le cadre de services mutuellement convenus, l’architecte peut aider le client à analyser les soumissions et lui présenter un rapport. Toutefois, c’est le client qui choisira l’entrepreneur à qui il confiera le contrat.

L’architecte examinera attentivement chaque soumission. Avant de présenter un rapport à son client, il analysera et cherchera les éléments suivants :

- l’exhaustivité de chaque soumission;

- le montant de la soumission et le montant des taxes à la valeur ajoutée;

- la date prévue du début des travaux et le calendrier des travaux;

- l’inclusion de tous les addendas;

- la liste des sous-traitants (avec vérification des références;

- la liste des fabricants et des fournisseurs (avec vérification);

- les substituts;

- les prix unitaires.

Il peut également être utile de faire un suivi auprès des architectes que ces entrepreneurs ont mentionnés dans leurs références. Enfin, l’architecte examinera avec soin l’impact financier des substituts et des prix unitaires contenus dans chaque soumission.

L’architecte doit faire un rapport écrit à son client sur les conclusions qu’il tire de son analyse, y compris une comparaison de tous les prix, et lui faire ses recommandations (normalement lui suggérer de choisir un entrepreneur qui satisfait le plus possible aux critères applicables).

Catégories de soumissions

On peut classer les soumissions en deux catégories :

- soumission conforme;

- soumission non conforme, c’est-à-dire une soumission qui pourrait être considérée informelle, irrecevable, incomplète, indûment qualifiée ou conditionnelle.

Une soumission est non conforme si :

- elle ne respecte pas les exigences élémentaires de la confidentialité (enveloppe non cachetée, par exemple);

- elle ne fait pas mention du nombre exact d’addendas reçus et pris en considération;

- elle n’est pas accompagnée du cautionnement (ou autre garantie) de soumission exigé;

- elle n’est pas signée ou scellée de façon appropriée;

- elle n’est pas accompagnée du « Consentement de garantie » exigé.

Voir aussi le CCDC 22 – Guide d’utilisation des cautionnements de construction.

Toute soumission jugée non conforme doit être rejetée.

L’architecte doit limiter ses conseils à un client en indiquant qu’une soumission est ou n’est pas conforme; les montants de la soumission; et que, au vu des documents d’appel d’offres fournis, il n’y a aucune raison évidente d’accepter ou de rejeter la soumission. Une recommandation à un client de conclure un contrat avec un entrepreneur particulier constitue un conseil juridique qui doit être fourni par le conseiller juridique du client, et non par l’architecte.

Dépassements

Lorsque même la soumission au plus bas prix dépasse la dernière estimation et que le client ne veut ni réviser son budget ni abandonner son projet, deux options sont possibles :

- si la différence par rapport à la dernière estimation du coût de construction approuvée est supérieure au pourcentage indiqué dans la convention client-architecte, la Formule canadienne normalisée de contrat pour les services de l’architecte – Document Six de l’IRAC stipule que l’architecte, si le client le lui demande, révisera les documents de construction et administrera un nouvel appel d’offres, sans honoraires additionnels;

- si la différence est inférieure à ce pourcentage, il est généralement possible de proposer des solutions de rechange et de négocier un prix acceptable avec le plus bas soumissionnaire.

Attribution du contrat

Lettre d’acceptation

L’attribution du contrat se fait généralement par la délivrance d’une lettre d’acceptation de la part du client. Cette lettre permet à l’entrepreneur de commencer les travaux immédiatement en attendant que le contrat soit officiellement rédigé et conclu. L’architecte aide souvent le client à préparer la lettre d’acceptation; toutefois, il devrait par prudence suggérer à son client de soumettre cette lettre et le projet de contrat à son conseiller juridique.

Le chapitre 6.8 – Formulaires modèles d’administration du projet propose un modèle de lettre d’acceptation.

Certains clients demandent à leur architecte de les aider à écrire à l’entrepreneur une lettre d’intention l’informant de leur intention de lui confier le contrat. Cette lettre, qui vise à obliger l’entrepreneur à demeurer disponible pour exécuter le projet sans un engagement réel, peut créer un malentendu, et il est préférable d’éviter cette façon de faire et de privilégier la lettre d’acceptation.

Lettres aux soumissionnaires non retenus

Les soumissionnaires non retenus doivent être informés rapidement de l’attribution du contrat, ce qui leur permet d’aviser leur société de cautionnement, d’affecter leur personnel à d’autres tâches, de libérer leurs sous-traitants et de soumissionner sur d’autres projets.

Le chapitre 6.8 – Formulaires modèles d’administration du projet propose un modèle de lettre aux soumissionnaires non retenus.

Préparation du contrat

C’est généralement l’architecte qui prépare le contrat de construction. Il est recommandé d’utiliser les formules de contrat normalisées du Comité canadien des documents de construction (CCDC). Ces documents sont largement acceptés dans l’industrie de la construction et ils ont été testés et approuvés par toutes les organisations constituantes du CCDC.

Le contrat de construction

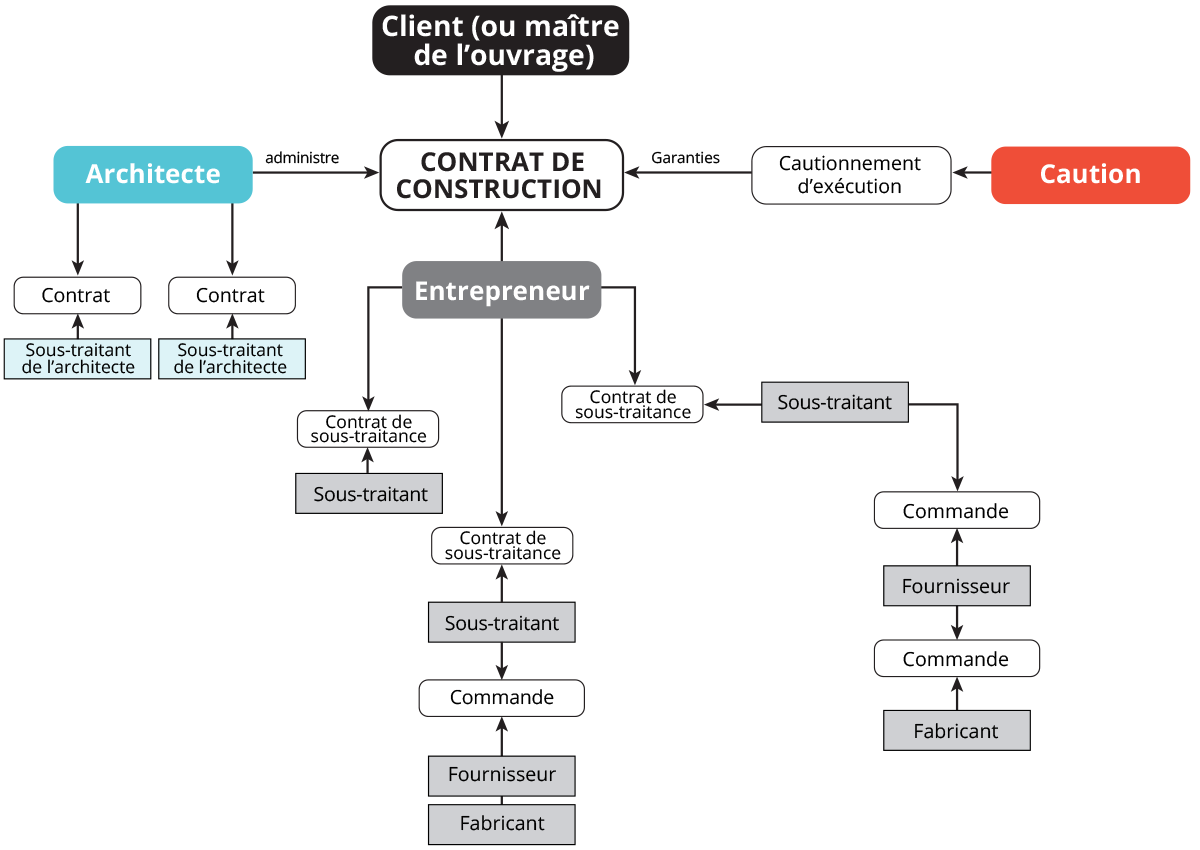

FIGURE 1 Relations dans un contrat à forfait tel que le CCDC 2

Voir le chapitre 2.1 – L’industrie de la construction, Annexe A – Liste – Formules de contrat et guides du Comité canadien des documents de construction.

Le nombre de copies du contrat devant être signées dépend du maître de l’ouvrage et de son avocat. Il doit y avoir au moins deux copies originales portant les sceaux d’autorisation du CCDC (un exemplaire pour le maître de l’ouvrage et un pour l’entrepreneur), plus une photocopie pour l’architecte. Les deux originaux doivent porter la signature des deux parties (et les sceaux des sociétés). Le document CCDC 20 – Guide d’utilisation de CCDC 2, explique comment remplir la convention placée au début de la formule de contrat CCDC 2 – Contrat à forfait.

Certains avocats recommandent de relier et de sceller les jeux de documents, de manière à ce qu’il soit difficile d’en retirer ou d’y ajouter des pages sans briser le sceau. On peut sceller les documents de l’une des façons suivantes :

- au moyen d’un ruban traversant le jeu de documents et dont les extrémités sont scellées avec un cachet de cire posé sur la page couverture;

- au moyen d’un fil de fer et d’un sceau en plomb.

Pour de petits projets, des méthodes plus simples sont acceptables. Pour conclure le contrat, le maître de l’ouvrage et l’entrepreneur doivent tous deux apposer leur signature sur la page couverture du jeu de dessins et du cahier des charges, et y apposer leur sceau. Parfois, les parties paraphent, en plus, chaque page des conditions supplémentaires et chacun des dessins. Un ensemble de contrat est alors remis au maître de l’ouvrage et à l’entrepreneur pour leurs dossiers.

Références

CARSON, John C. Carson’s Construction Dictionary: Law and Usage in Canada. Toronto, Ontario, Toronto Construction Association, 1989.

COMITÉ CANADIEN DES DOCUMENTS DE CONSTRUCTION (CCDC). CCDC 23 – 2018 : Guide des appels d’offres et de l’attribution des contrats de construction, CCDC, 2018.

COMITÉ CANADIEN DES DOCUMENTS DE CONSTRUCTION (CCDC). CCDC 00 – Devis directeur du CCDC pour la Division 00 – 2018 : Exigences relatives aux approvisionnements et aux contrats, CCDC, 2018.

CONSTRUCTION SPECIFICATIONS CANADA (CSC). Manual of Practice, Toronto, Ont., 2006. https://specmarket.com/products/csc-manual-of-practice-complete-english.

MURPHY, Tim et Leonard Ricchetti. Construction Law in Canada, New York, LexisNexis, 2010.

SANDORI, Paul et William Pigott. Bidding and Tendering: What Is the Law? 5th edition, New York, LexisNexis, 2015.