Definitions

Certificate: A document attesting to the truth of a fact; in construction, a certificate is prepared by a professional, either an architect or an engineer.

Certificate of Substantial Performance: A certificate issued under the appropriate lien legislation attesting that the contract between the owner and the contractor is substantially complete.

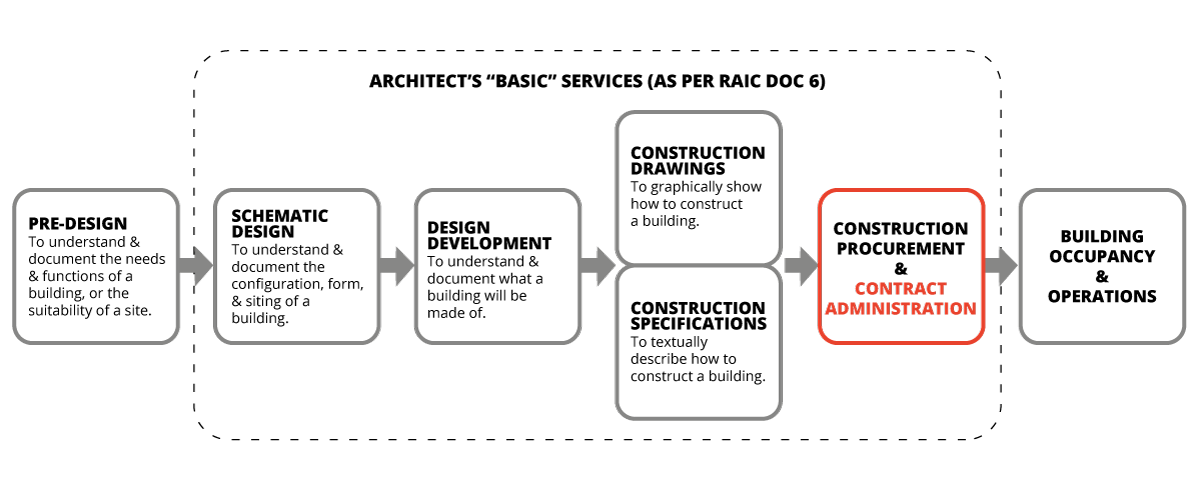

Contract Administration: The services provided by an architect during the construction phase of a project. For stipulated construction price contracts, these services are outlined in detail in in one of the Schedules of Architect’s Services which accompany the Canadian Standard Form of Contract for Architectural Services – RAIC Document Six.

General Review: General review is synonymous with field review. It is review conducted by the architect and consultants during visits to the place of the work and, where applicable, to locations where building components are fabricated for use at the place of the work, at intervals appropriate to the stage of the construction, that the architect and consultants in their professional discretion consider necessary to become familiar with concerning the progress and quality of the work, to determine that the work is in general conformity with the construction documents and to report in writing to the client, the constructor and authorities having jurisdiction.

Holdback: A percentage of the monetary amount payable under a (construction) contract, which is held as security for a certain period of time. The percentage and period of time are based on the provincial lien legislation.

Instruments of Services: Instruments of service are representations, in any medium of expression, of the tangible and intangible creative work that forms part of the services or additional services.

Lien: A legal claim on real property to satisfy a debt owed to the lien claimant by the property owner. This claim can carry the right to sell the property upon default.

Shop Drawing: A drawing, diagram, schedule or data prepared on behalf of the contractor to indicate precise details of the construction materials, products or installation. Usually prepared by the “shop” or the trade, or the manufacturer, supplier or fabricator responsible for the particular product.

Introduction

An architect provides the services known as “contract administration.” Many jurisdictions and provincial and territorial associations now require professional involvement in the construction phase of most building types. Clients do not always value the professional services provided for contract administration, and sometimes try to reduce or eliminate the role of the architect during this phase.

At the start of construction, in a traditional design-bid-build contract, a new participant – the contractor – is introduced to the project and takes on the responsibility and control of the construction. The architect also takes on new responsibilities as described in the construction contract. These responsibilities support both the client’s and the contractor’s interests in the successful completion of the construction phase.

With other forms of project delivery, the architect’s relationship with the contractor may vary. This chapter is written with the assumption that the architect is administering a stipulated sum contract using the design-bid-build approach (Canadian Construction Documents Committee construction agreement CCDC 2 in Canada) for a project in which the client has directly engaged the architect using a client-architect agreement such as the Canadian Standard Form of Contract for Architectural Services: RAIC Document Six, hereafter RAIC Document Six, and the architect is the managing or prime consultant for the building project. Regardless of the form of contract, the architect’s responsibilities will be similar for the construction management approach. Notwithstanding the method of design-construction project delivery, the architect has regulatory responsibilities to determine that the work is in general conformity with the contract documents that cannot be removed and avoided by contract.

The office functions and field functions of contract administration are done concurrently and in a coordinating fashion. The term “office functions” is used to describe those activities commonly associated with review of documents and samples submitted for review and/or approval, construction contract change management, contractor payment application review and certification, and other activities not conducted at the place of the work. The terms used to describe the field functions of contract administration and activities conducted on site or out of the office are:

- field review;

- general review;

- site review;

- site observations.

In addition to use of these terms in construction contracts and general parlance, legislation and regulations governing building code compliance may use defined terms, such as “general review,” to describe the responsibilities of the architect and engineers to protect the public interest during construction. These regulatory responsibilities encompass work both on site and in the office.

The terms “supervision” and “inspection” refer to completely different levels of service not normally provided by an architect.

- Supervision implies the overseeing of the construction work, including the activities undertaken by workers on site, which is the responsibility of the contractor, not the architect.

- Inspection means a “close examination” (of construction); once again, this level of service is beyond the architect’s responsibilities.

The architect’s duty during general review is to carry out sufficient periodic site visits at appropriate intervals during the various stages of construction to determine if the work is in general conformity with the contract documents. In addition, the architect reports on the progress of the work and observations made on site.

Purpose of Contract Administration

Contract administration describes the services provided by the architect or contract administrator to fulfill the roles in standard construction contracts such as those duties outlined in General Condition GC 2.2 of CCDC 2 – Role of the Consultant. The construction contract also describes the respective roles and obligations of the contractor and the client. In addition, contract administration provides an opportunity for the architect to assist in realizing the project by providing the contractor with technical interpretations and information.

The resources, money, time and effort invested in the development of the project, as well as the value of the completed work, require that the contractor’s performance be reviewed throughout the construction period. In addition, the contractor relies upon the architect for services such as general review, submittal review, etc.

The nature of the project, the type of construction contract, and the method of contract award and project delivery, as well as the architect’s agreed-to services and fees, all have a direct bearing on the level and scope of the monitoring that will be required. For example:

- an open and public tender, or a more technically sophisticated project in a fixed-price contract, may require more effort in contract administration as the contractor selected through a lowest-price method may not have the optimal level of experience or capability;

- a simple project or a project under a cost-plus type contract awarded to one of a pre-selected list of contractors may require much less contract administration as the contractor, receiving compensation for all expenses and/or being selected specifically for their expertise, may be less inclined towards adversarial approaches to resolving conflict;

- a tight construction schedule will generally require more review than one with fewer time constraints as the construction activities happen at an accelerated rate, therefore requiring shorter lead times in approvals and reviews.

The nature and scope of the architect’s services during the construction phase are defined by both the construction contract (such as CCDC 2) and the client-architect agreement (such as the Canadian Standard Form of Contract for Architectural Services: RAIC Document Six). For every specific project, the executed client-architect agreement and the construction contract, as well as their supplementary conditions, need to be reviewed by the contract administrator as there may be ambiguous, contradictory or conflicting provisions between these two basic agreements. Conflicts between the two agreements or between agreements and client-generated supplemental conditions should be resolved prior to the execution of either contract.

Purpose for General Review

The architect’s activities on the construction site include four main functions:

- review the contractor’s performance in maintaining both the construction schedule and the standards or quality of construction;

- provide guidance to the contractor by interpreting the contract documents, answering questions verbally and, when required, issuing necessary documentation, including supplemental instructions, proposed changes, change directives or change orders in order to allow the progress of work on site;

- fulfill performance standards for general review as required by the client-architect agreement, authorities having jurisdiction, and provincial or territorial associations of architects;

- analyze and adjust the contractor’s application for payment and certification of the payment.

General reviews are essential to the project’s success. To achieve these four functions, the architect must perform these reviews personally or assign a qualified experienced staff member who is properly trained to perform site reviews. Interns may also assist with these tasks and, with the proper supervision, guidance and mentoring from the architect, gain the experience needed to perform these reviews. It may be useful to prepare a manual with proper procedures for site personnel.

Site activities should follow these principles:

- comply with provincial/territorial safety regulations as well as any reasonable additional requirements of the contractor, e.g., personal protective equipment (PPE) such as hard hat, safety shoes, safety glasses, etc.;

- carefully describe to the client the architect’s duties and role during the construction phase and adhere to these responsibilities;

- keep the client well informed of the progress of the work, in part by sending copies of site observation reports to the client and all appropriate parties;

- ensure that consultants review their portion of the work and submit site review reports;

- review rather than inspect or supervise the work in all documentation – avoid the latter words;

- keep proper documentation such as reports, logs, photographs and video recordings;

- promote good communications with the contractor and building officials.

The Role of the Architect

The nature and scope of the architect’s services during the construction contract administration phase are outlined in the client-architect agreement. As well, the architect’s role is described in many construction contracts. For example, Part 2 of CCDC 2 “Administration of the Contract” clearly outlines:

- the authority of the consultant;

- the role of the consultant;

- the consultant’s role in correcting “defective work.”

In addition, if the consultant is unable to resolve differences between the client and the contractor regarding “the interpretation, application, or administration of the contract,” the consultant is obligated under “Dispute Resolution” (Part 8, CCDC 2) to provide instructions to prevent delays in the event of a dispute.

Office Functions

The architect’s specific office functions include:

- representing and providing advice to the client;

- review of the construction schedule and contractor’s schedule of values;

- preparing all documentation for the contractor and the client and others, including:

- supplemental instructions;

- site review reports;

- change orders;

- change directives;

- summary of change orders;

- certificates;

- coordinating the services of consultants;

- evaluating the contractor’s proposed substitutions and progress claims;

- reviewing shop drawings;

- reviewing operating and maintenance manuals at project close-out;

- rendering interpretations;

- following up with warranty items during the warranty period.

Field Functions

The architect’s role in a project changes from designer to contract administrator once the construction of a project is underway. Refer to the Schedules of Architect’s Services which accompany the Canadian Standard Form of Contract for Architectural Services: RAIC Document Six for a comprehensive list of the architect’s responsibilities during the construction phase of a project.

The architect is both a representative of the client and an interpreter of the contract documents. Normally, the architect is present on site to:

- conduct a general or field review;

- attend site meetings;

- interpret contract documents or resolve problems;

- observe testing or other procedures;

- review and accept samples, mock-ups, etc.;

- meet with consultants, contractors or the client regarding the progress of the construction;

- determine the percentage of the work completed (information which is used to prepare certificates).

In most agreements, the architect is not required to make exhaustive inspections or continuous on-site review.

Nor is the architect responsible for the construction methods or procedures, or for construction safety. However, the architect should understand workplace safety and practise “due diligence” on the construction site. Although an architect is not responsible for safety on the construction site, the architect is responsible for the safety of all firm employees. Visiting a construction site carries with it inherent risks, and the architect must take responsibility for ensuring that employees are trained and prepared to conduct reviews on a construction site. See “Safety on the Construction Site” below.

The Role of Others in Contract Administration

Generally, the architect communicates with many project stakeholders who are involved in the construction project and may visit the site during this phase, including:

- the client or designated representative;

- the consultants and the architect’s own design team;

- the contractor, subcontractors, and suppliers;

- authorities having jurisdiction;

- inspection and testing firms;

- other institutions, such as lending institutions and insurance agents.

The Client

The client, or owner, is the entity that has entered into a contract with the contractor. The client’s basic responsibilities during the construction project are:

- providing financing information if required;

- making payments to the contractor;

- authorizing changes in the work and/or contract price;

- providing prompt decisions and directions.

There are many different types of client. For some, it will be their first endeavour in design and construction. Here, the architect will likely play a larger role in educating and advising the owner. There are also very sophisticated owners who have a staff of professionals dedicated to the project and who understand the design and construction processes. These knowledgeable clients may be more involved in some or all phases of a project. Architects will need to adapt their communication style to the various types of clients.

Clients may be represented by designated representatives or:

- an advocate architect, who is a third-party subject matter expert who provides professional advice to the client and who will represent the client’s interests during the process of an architectural project. The advocate architect may act as the designated representative of the client/owner, ensuring their needs are being met while carrying out compliance evaluation through planning, design and construction. See Chapter 3.10 – Appendix D – The Architect as Advocate Architect/Compliance Architect/Design Manager/Researcher for additional information about this role.

- a project manager, whose duties are generally not governed by legislation or regulation. In general, where a project manager is involved in a project, the responsibilities of the consulting project manager should be described in supplementary general conditions to client-architect and client-contractor agreements. Any variations to standard contracted requirements will likely constitute additional services by the architect. See Chapter 3.10 – Appendix C – The Architect as Project Management Service Provider for additional information about this role.

- a clerk of the works, who provides a more frequent presence on site for added assurance. A clerk of the works becomes the eyes and “boots on the ground” for daily progress, monitoring and reporting, and would usually be situated very close to the job site (often accommodated in the site trailer). For more information, see Appendix B – Continuous On-site Representation at the end of this chapter.

Consultants

Consultants will include those engaged by the managing or prime consultant, typically the architect. They may also be engaged directly by the client through separate contracts. The managing or prime consultant’s role includes the coordination of consultants regardless of who has signed their contracts. The many roles of consultants are noted below.

Consultants assist the architect in office functions by:

- reviewing relevant shop drawings;

- interpreting their part of the contract documents;

- issuing supplemental instructions on their part of the contract documents;

- assisting in the preparation of change orders when required;

- reviewing their portion of the work to determine the percentage complete (which assists the architect in the preparation of certificates for payment);

- providing advice to assist the architect in the preparation of other certificates.

The field functions of consultants are also critical to the success of a project. Typically, the architect is responsible for notifying and coordinating consultants as well as ensuring their attendance on site at the appropriate times, such as for specialized meetings, progress claim reviews, tests, etc. Consultants usually review the portion of the work which they have designed or for which they are responsible. They also determine whether their portion of the work is in general conformity with the contract documents and determine deficiencies and non-conformances in the construction work and report same to the architect. In addition, consultants assist the architect in preparing certificates for payment by attesting to the value of their portion of the work that has been completed. Consultants may also be involved in answering requests for information (RFIs), and reviewing mock-ups and other inspection and testing procedures.

The Contractor

The contractor is responsible for the execution of all the work, means and methods required to carry out the construction work as described in the contract documents. The role of the contractor is described in a construction contract, such as CCDC 2, and in the project specifications.

Generally speaking, the contractor is responsible for maintaining an acceptable quality of every element of the construction, and the construction means, methods, and procedures. Consultants review the work on site, observing samples of the work to verify compliance of the work with contract documents. Consultants also provide “general review” of building code compliance related to their responsibilities under provincial and territorial regulations to protect the public interest. These are fundamental differences between the responsibilities of contractors and consultant, sometimes misunderstood by either party, or the client.

Specifically, the contractor:

- studies the contract documents and fulfills all requirements including regulatory requirements to the extent provided for in the contract documents;

- supervises and coordinates the work of all trades and subcontractors;

- executes the work by selecting all construction methods, techniques, sequences, etc.;

- is usually responsible for construction safety and all workplace regulations;

- pays for all labour, products and subcontracts.

The contractor is responsible for site safety and for supervising the workers and coordinating subcontractors. Depending upon a project’s construction value, most contractors will assign one or more individuals to manage the project. The contractor’s primary on-site representative is known as a project manager (PM) and is tasked with the administration roles, which include: creating and managing the schedule; managing RFIs, submittals, supplemental instructions and changes to the work; preparing the schedule of values and monthly progress invoice. They may manage multiple projects at once. Often, project managers will be assisted by a project coordinator, who will execute many contractor’s office functions under supervision, such as managing RFIs, submittals, mock-ups, meeting minutes, etc. The PM will rely upon one or more site superintendents to manage activities on the site. The site superintendent is usually assigned to only one project at a time, frequently setting up a temporary office in a construction trailer or part of a building which is under renovation. In addition to managing day-to-day progress of the work, the superintendent identifies and manages resolution of non-conformances and deficiencies as they arise, including those noted by the architect and consultants. The contractor usually contacts the architect at varying stages of the project to schedule meetings and general or specific reviews as well as mock-ups.

Safety on the Construction Site

The contractor is generally solely responsible for construction safety at the workplace and for:

- complying with the rules, regulations and practices required by the applicable occupational health and safety legislation;

- initiating, maintaining and supervising all safety precautions and programs in connection with the performance of the work.

An exception may be if the owner has awarded separate contracts to the trades and/or is using the owner’s own forces for parts of the project; the legislation of some provinces and territories may define the owner, rather than the contractor, as the constructor in these situations. When this is the case, obligations of all parties should be clearly outlined in the client-contractor contract.

Although not responsible for construction safety, the architect should review all applicable provincial and territorial occupational health and safety legislation and regulations to determine the architect’s responsibilities in the workplace.

If an unsafe or life-threatening situation is observed, the architect is obliged to report this immediately to the contractor and the owner, and to record the verbal site discussions. Architects do not have a contractual obligation to report safety issues on a site; however, architects have a responsibility in tort as does every individual to do so. If an issue is noticed and not reported, an architect may assume responsibility for, or be liable for, contributory negligence for those unsafe practices observed.

While the constructor is responsible for site safety, architects, both personally and in their role as employers, are responsible for ensuring that they and their staff are properly trained to deal with the workplace hazards they may encounter. Nevertheless, when developing the scope of the architect’s services in discussions with the client, always avoid inadvertently assuming responsibility for site safety, especially when offering full-time clerk of work, resident, or expanded field services. The architect should make it clear to the owner and the contractor that the architect is not responsible for:

- the means, methods, sequence, procedures, techniques, or schedule of construction activities;

- job-site safety;

- electrical and mechanical services.

See also Chapter 2.1 – The Construction Industry.

Construction Contract Administration Processes and Documentation

Construction contract administration functions “in the office” and “in the field” have been integrated as emerging technology and work environments are blurring the separation between these two traditionally distinct sets of activities.

Office and field functions for the contract administration phase of a building project include work undertaken at the following stages:

- prior to construction;

- during construction;

- at close-out;

- during the warranty period.

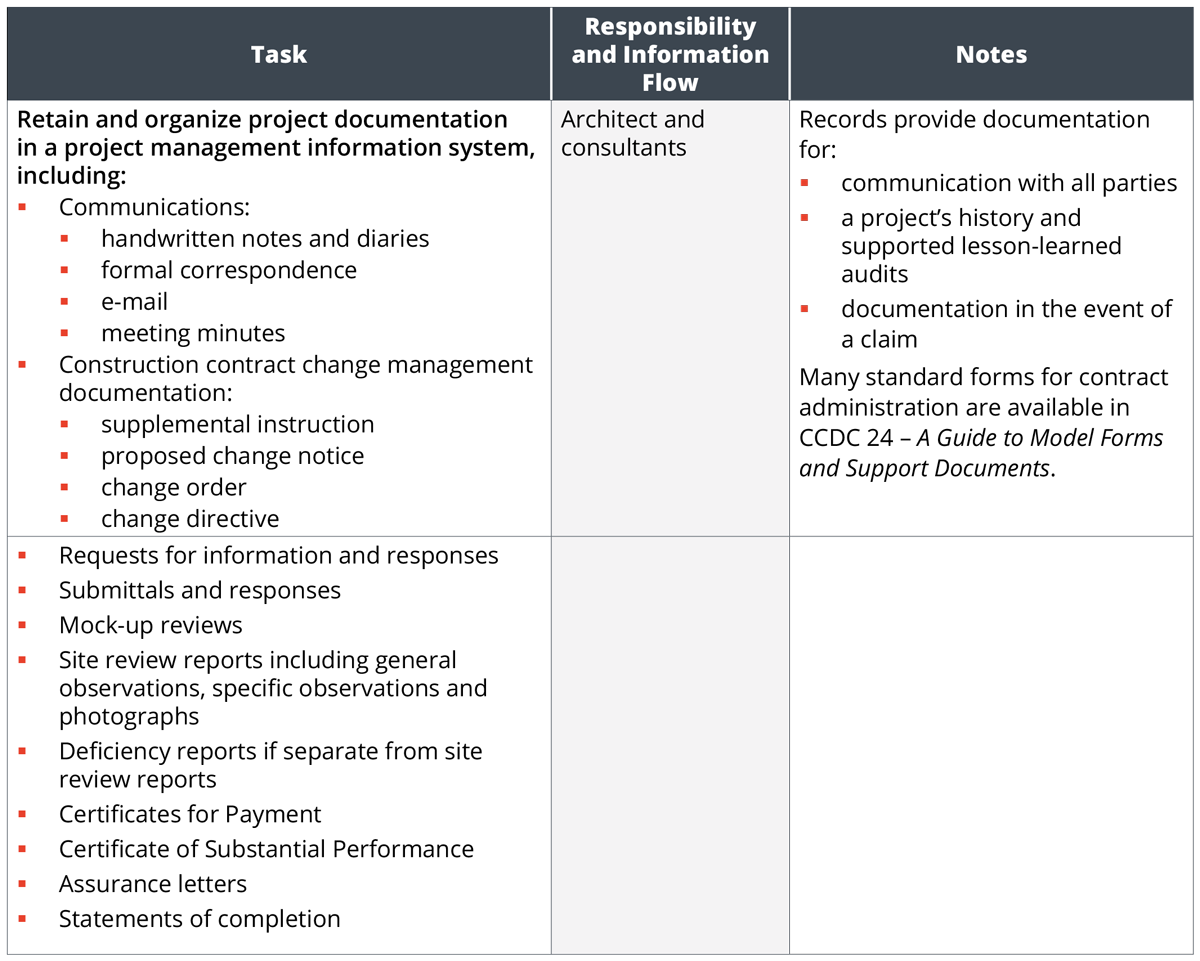

Documentation

Many of the functions of construction contract administration result in documentation. The architect must develop and manage accurate and thorough documentation during the construction phase of the project. This documentation assists in providing:

- a record of communication with all parties;

- a project history;

- documentation in the event of a claim.

Typical types of documentation include:

- formal correspondence and e-mails;

- minutes of meetings;

- supplemental instructions;

- change management documents;

- Certificates for Payment;

- other certificates:

- Certificate of Substantial Performance;

- Letters of Assurance;

- Statements of Completion.

The architect’s project management information system should facilitate the following functions:

- easily following an issue through general review, supplemental instruction, proposed change notice, and change orders with consistent narrative, numbering, and format of documents;

- a consistent information organization system for efficient filing, searching, retrieval and archiving by any member of the project team, regardless of their technical or administrative discipline of team role.

Many of these standard forms for contract administration are available in CCDC 24 – A Guide to Model Forms and Support Documents (for use with CCDC 2).

Checklists

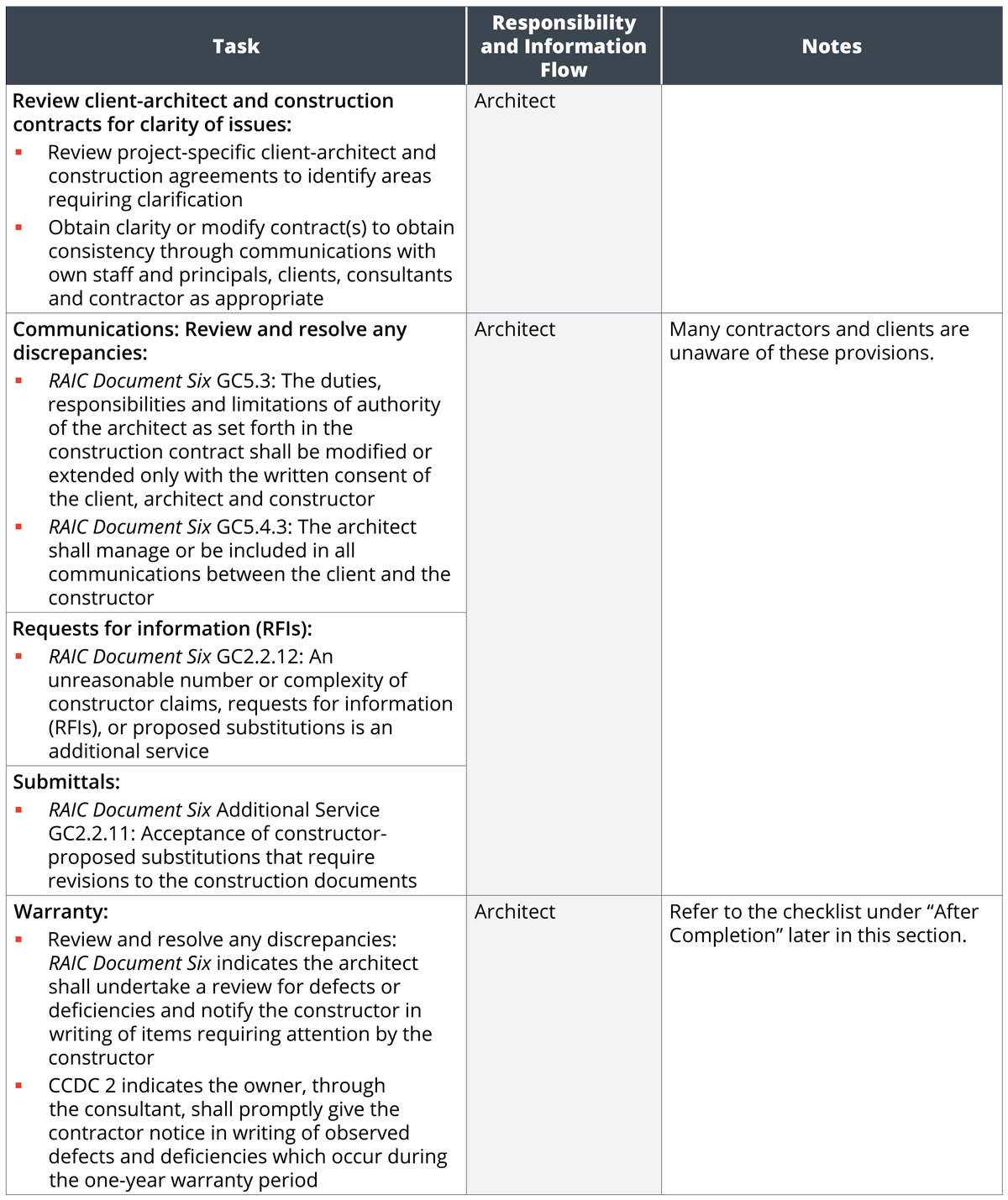

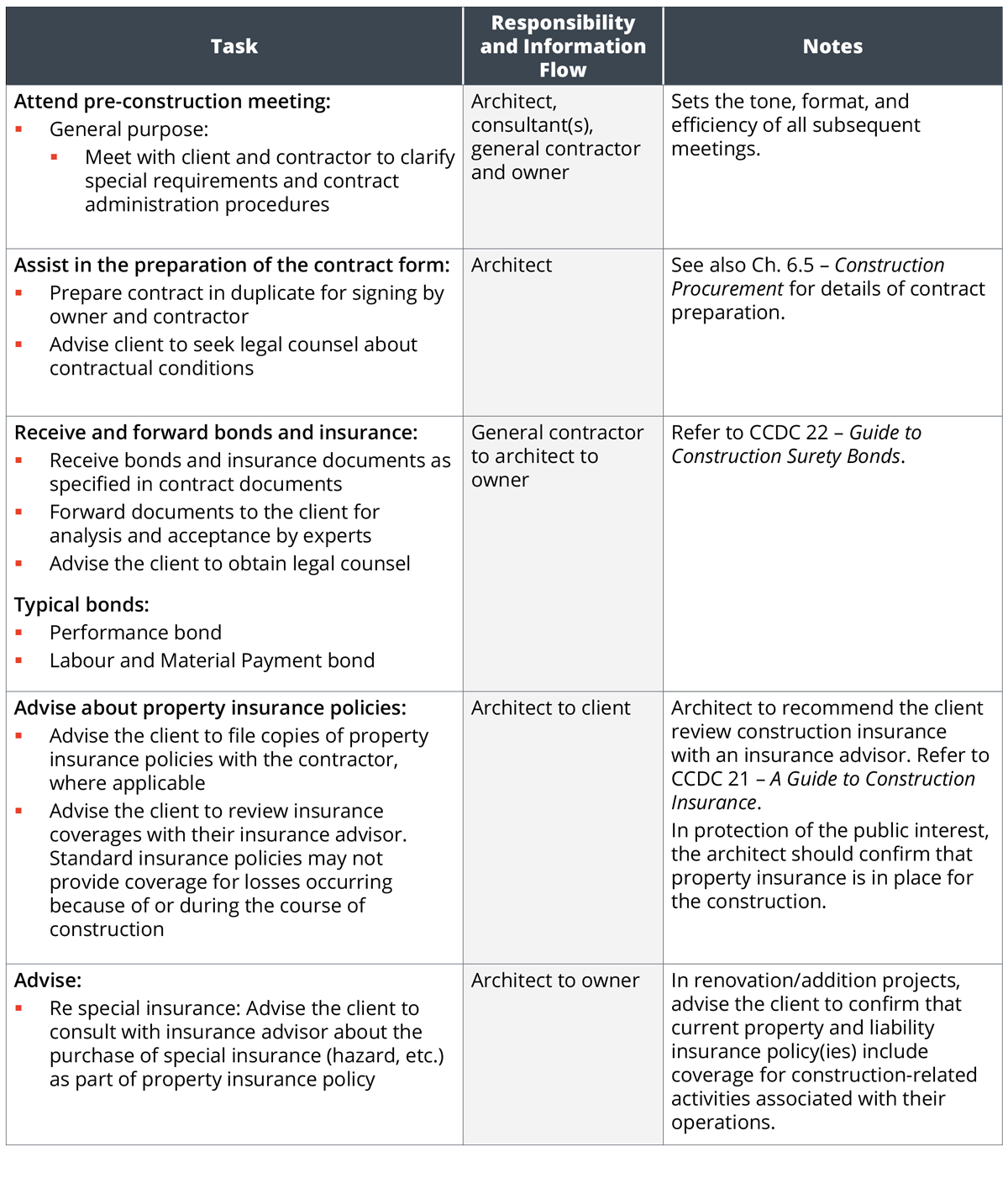

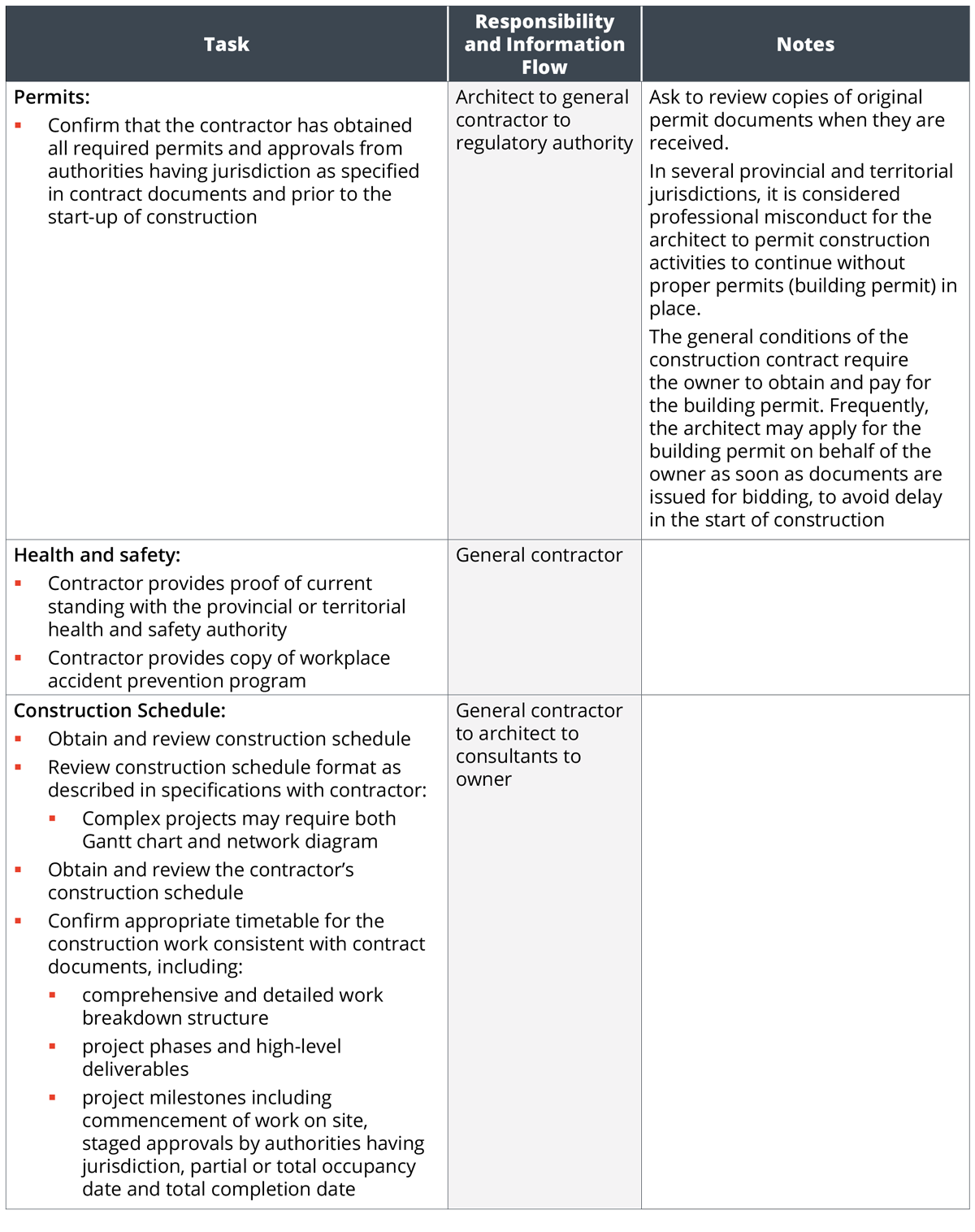

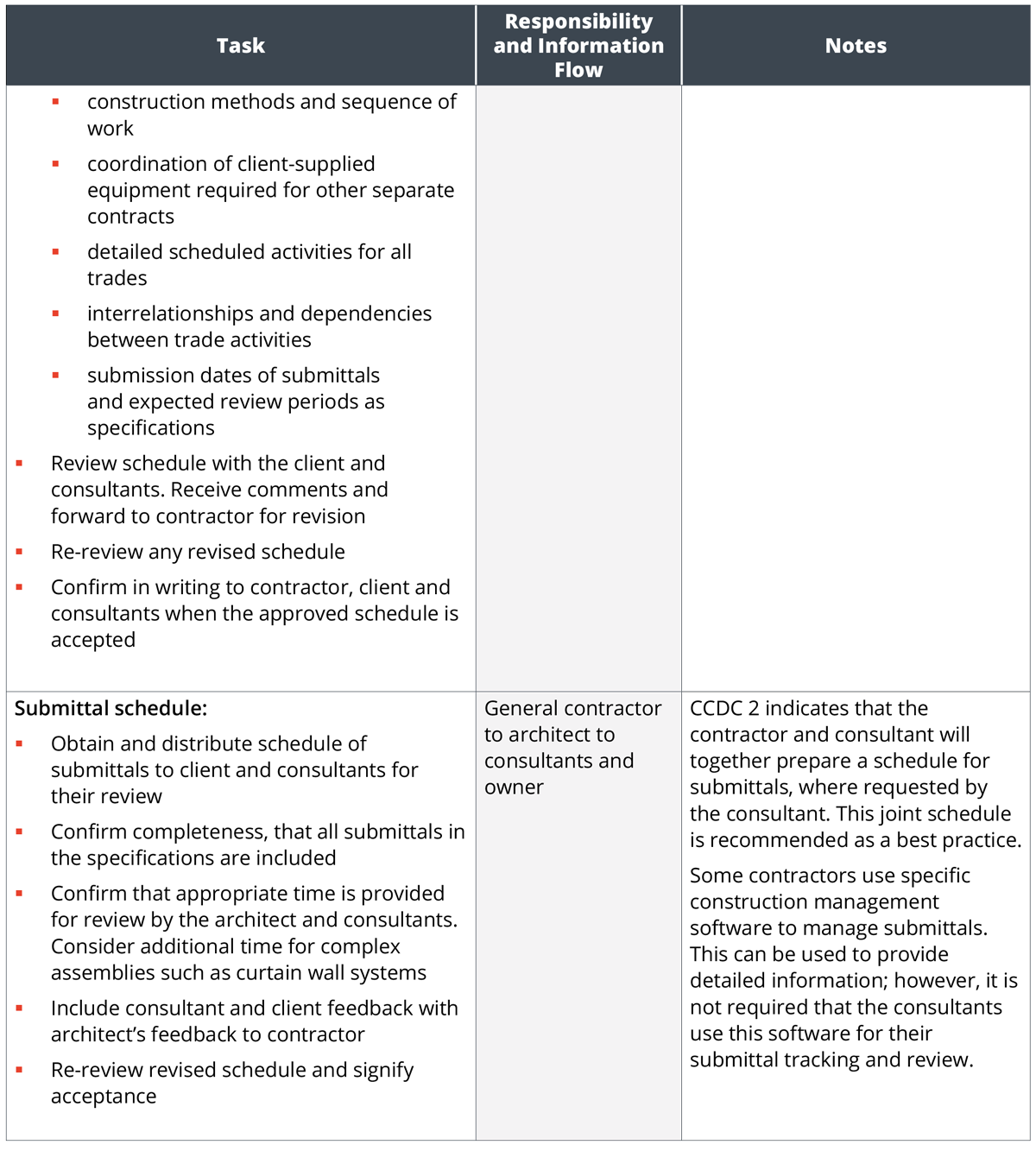

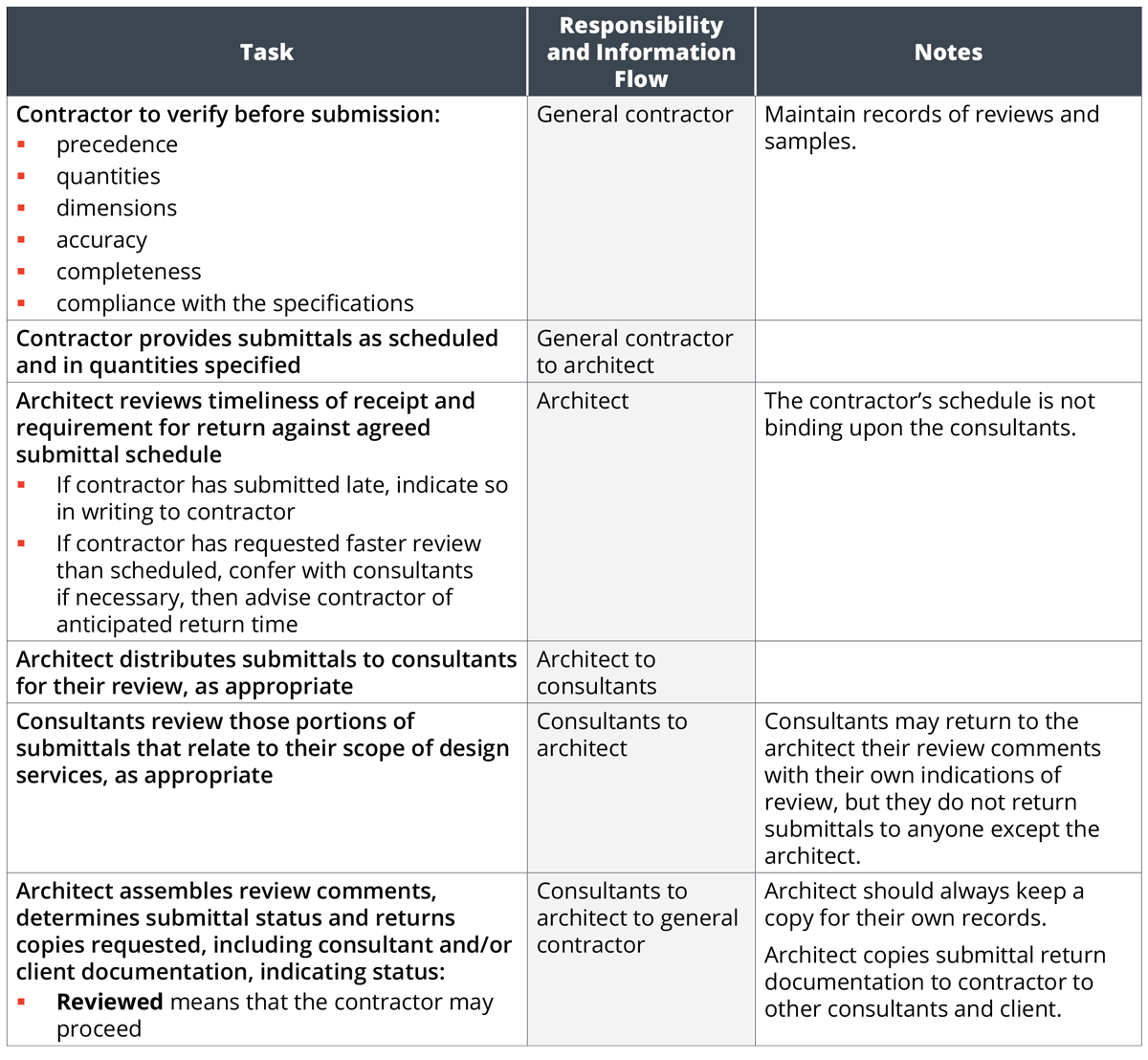

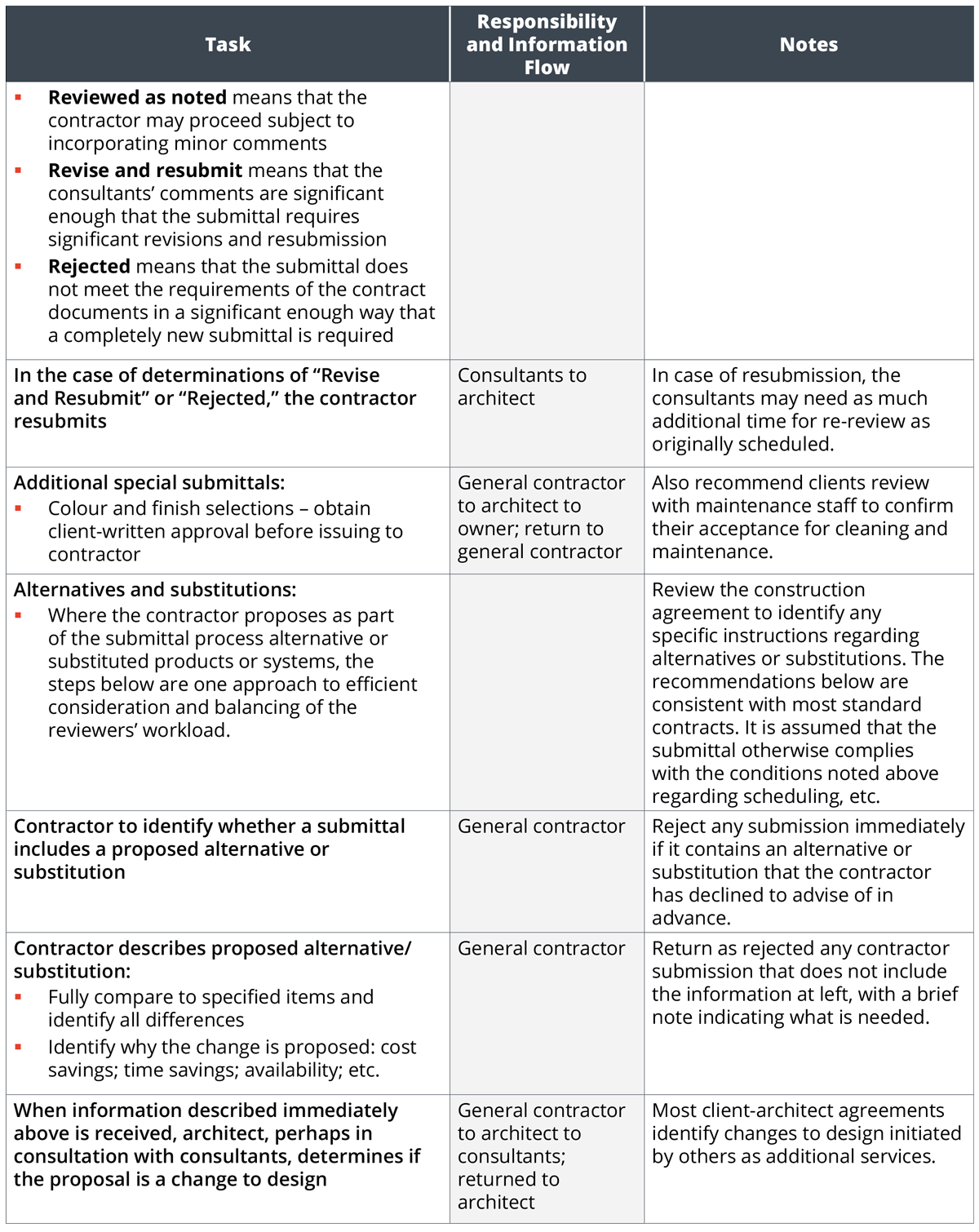

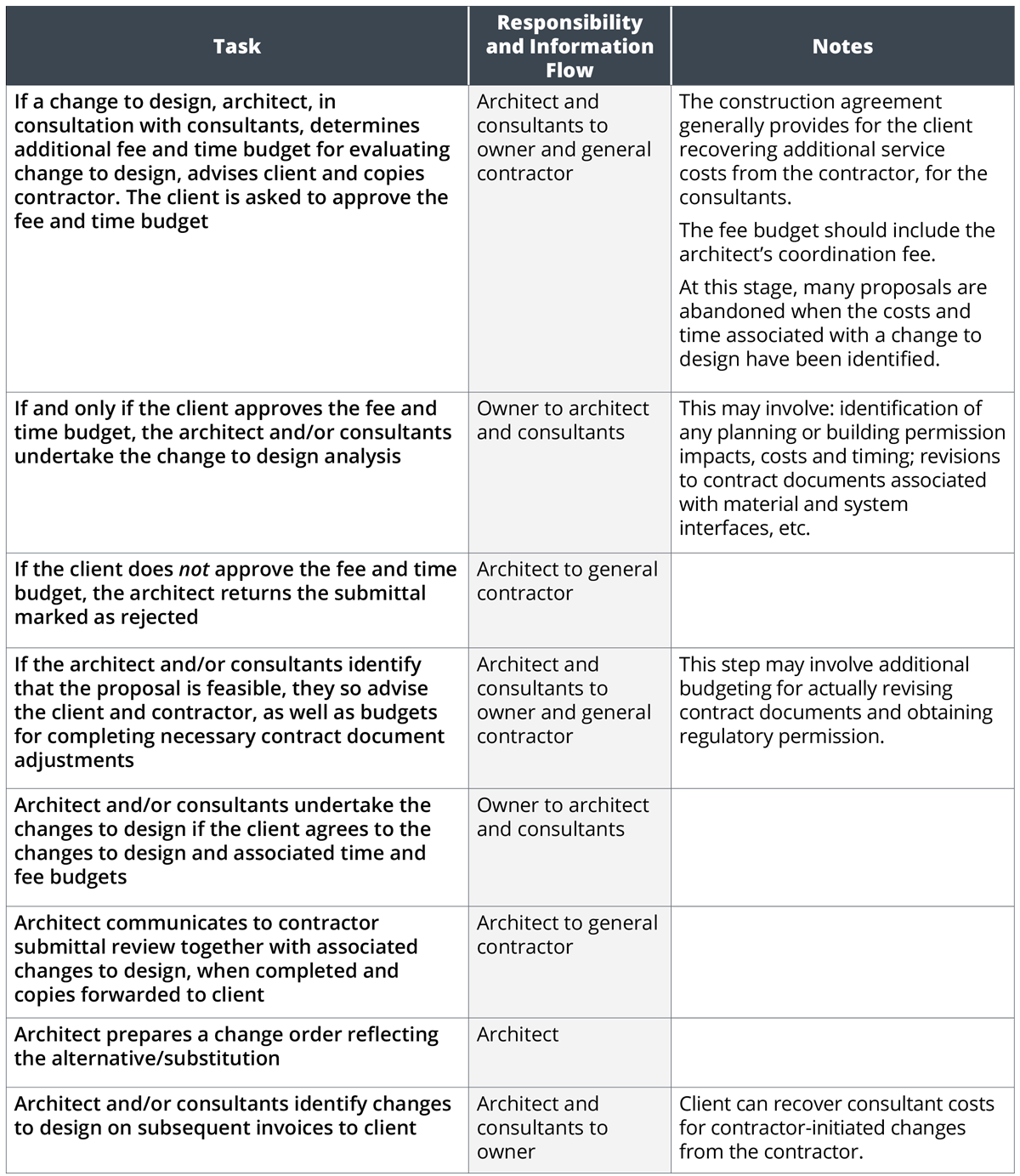

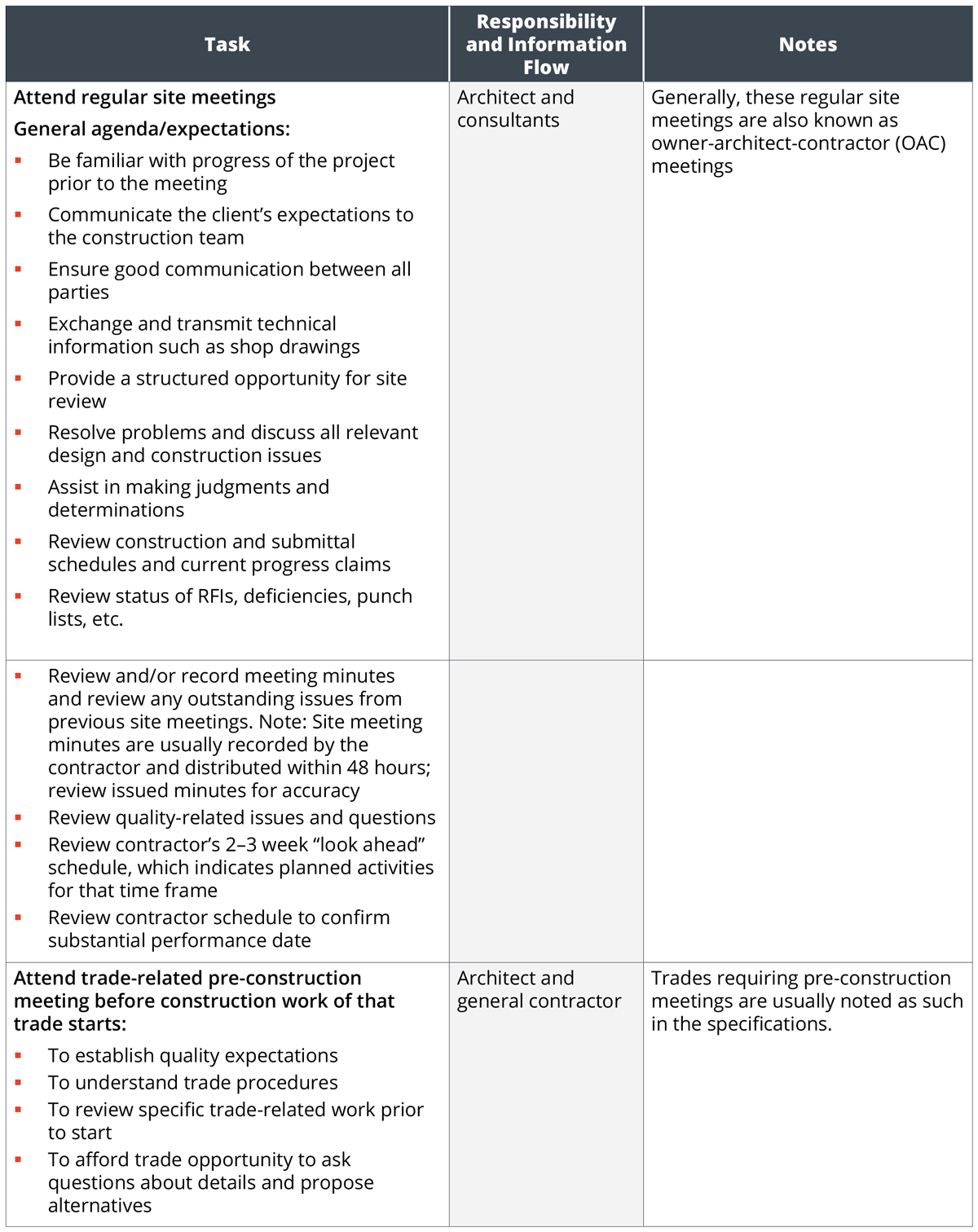

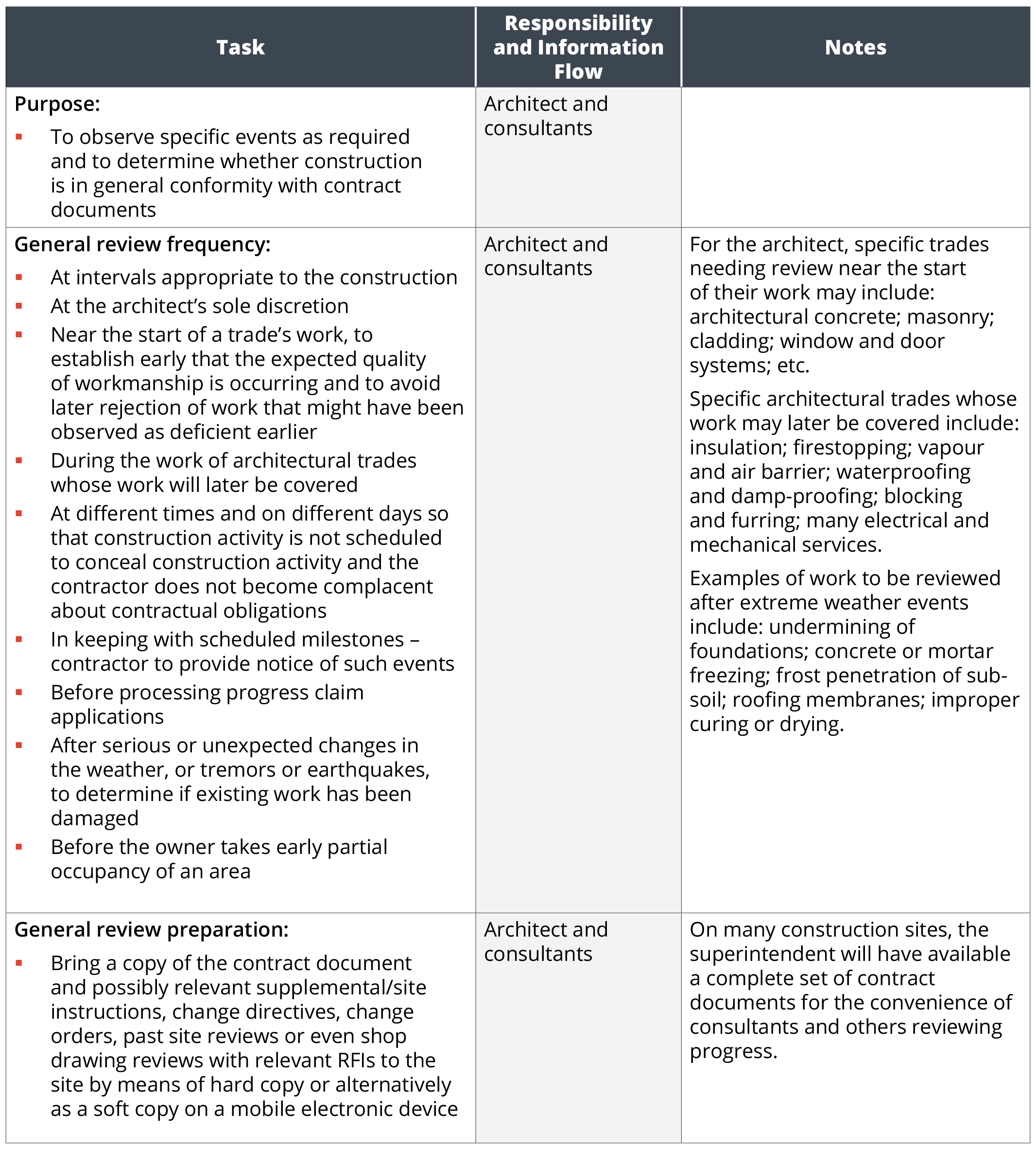

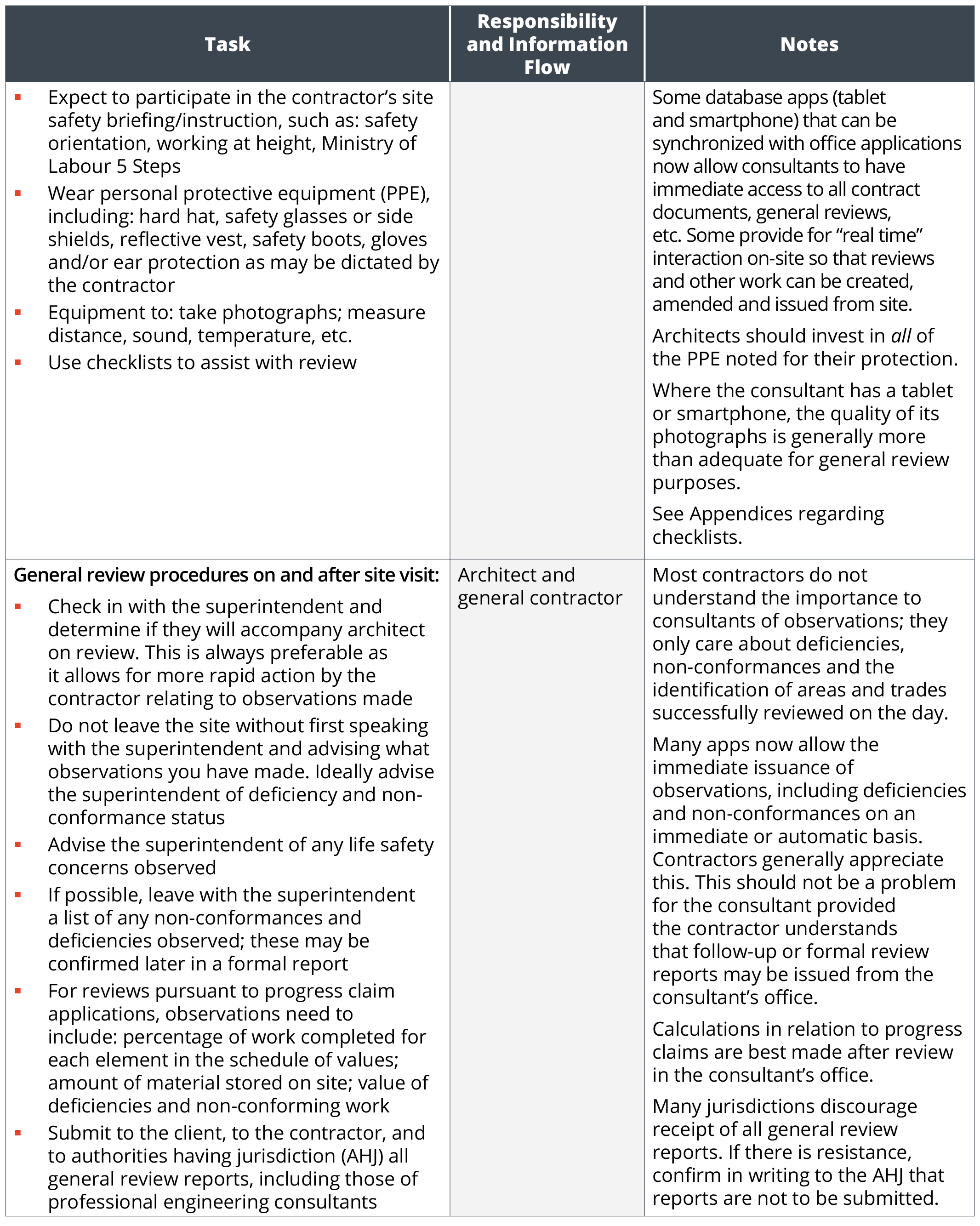

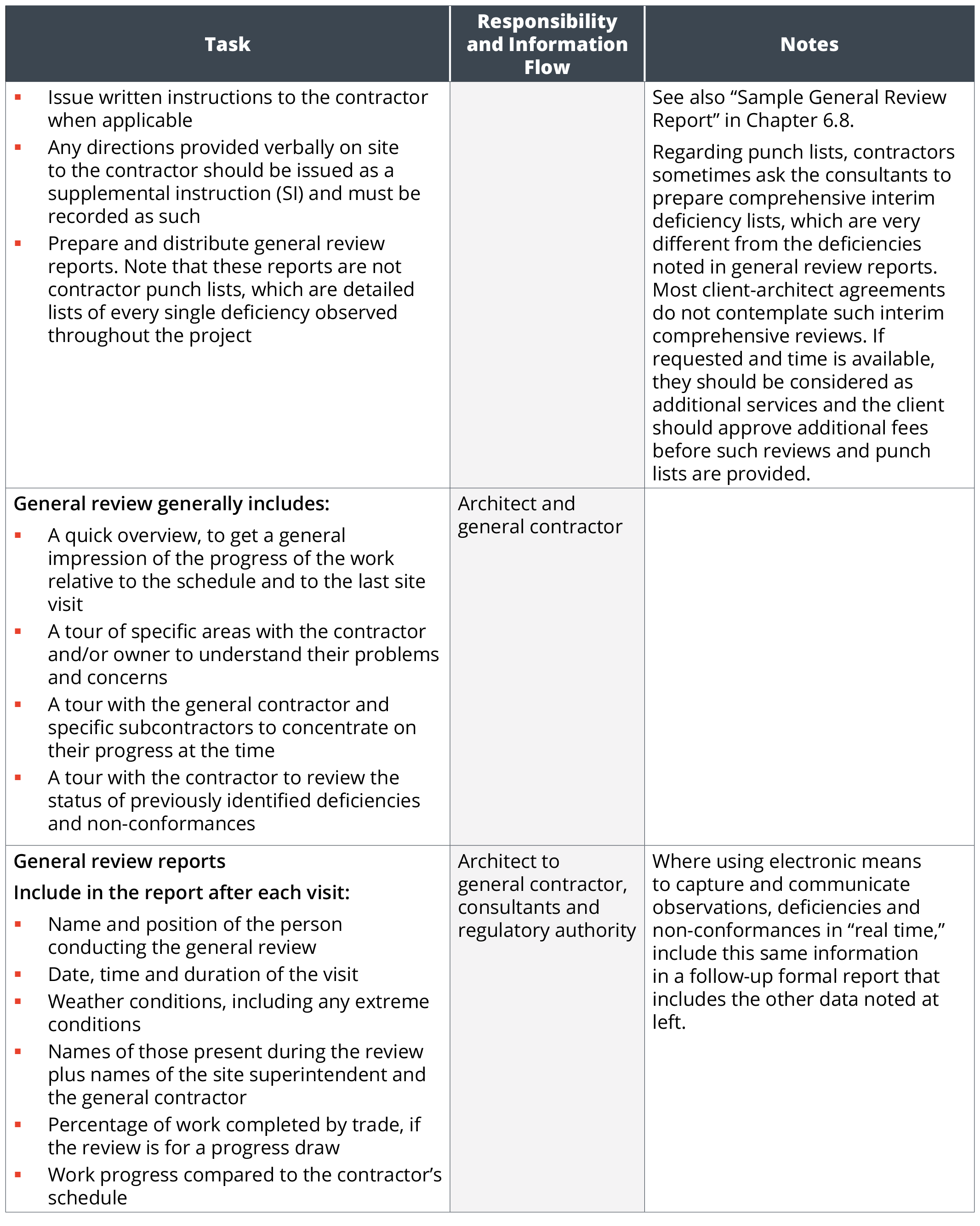

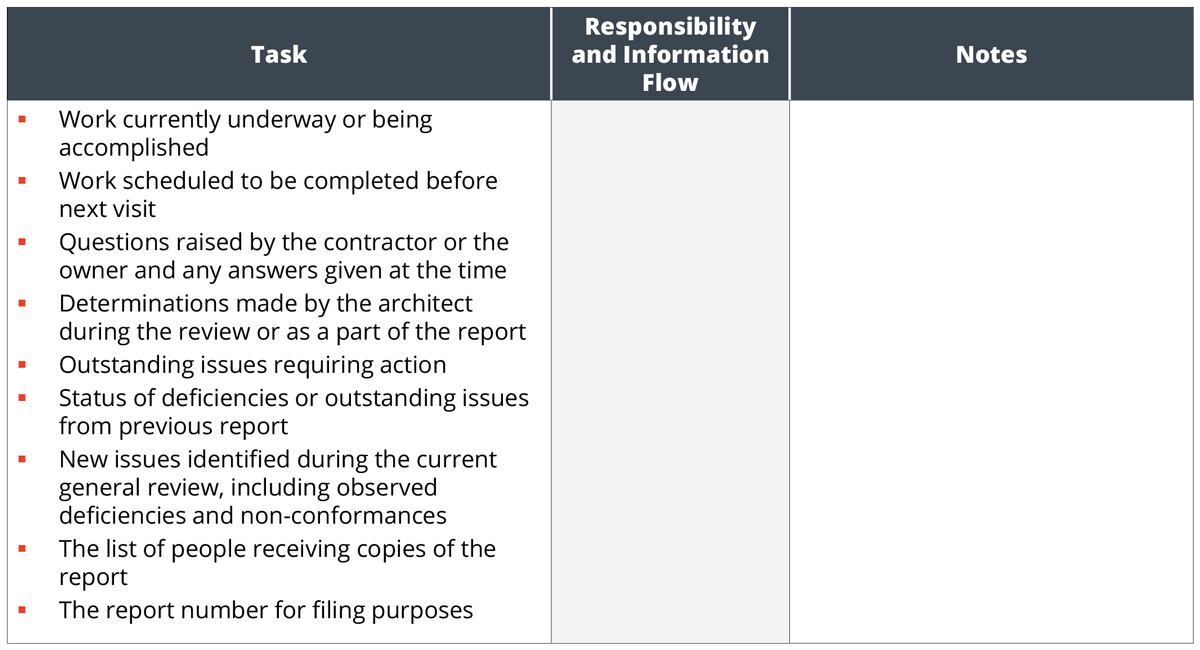

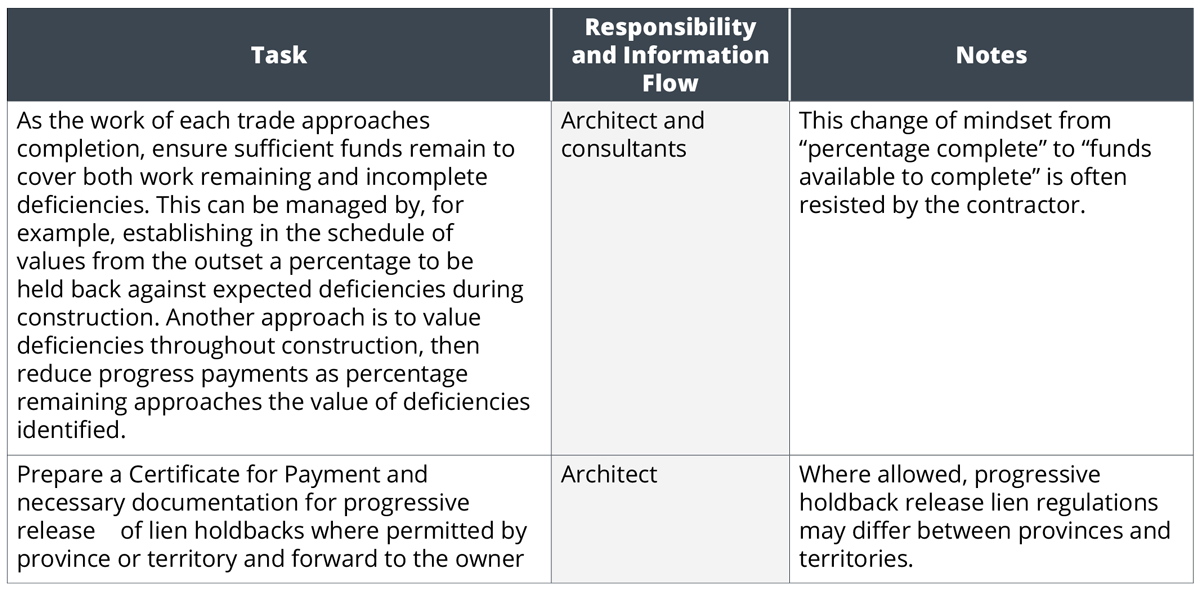

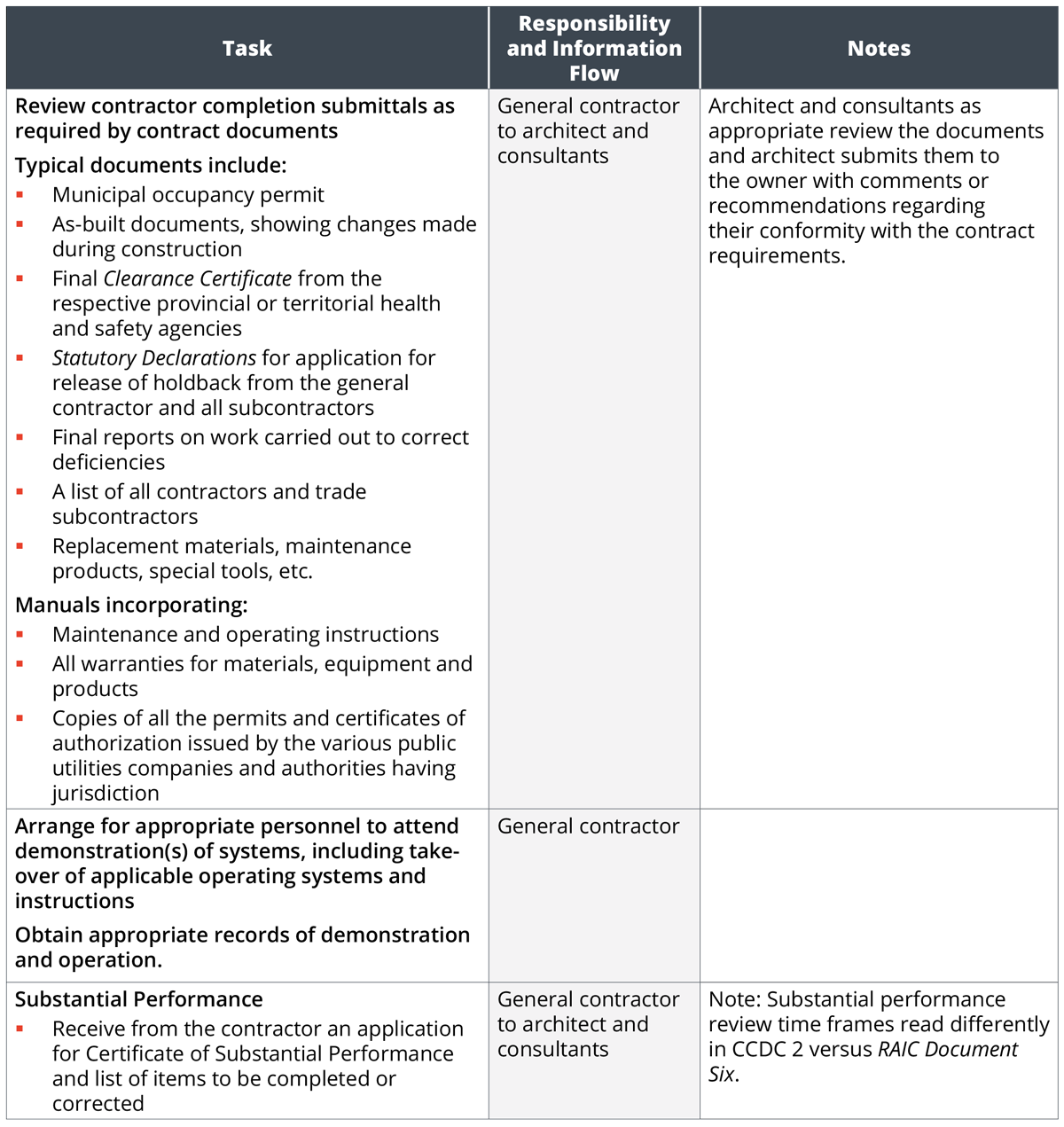

The architect’s contract administration functions are summarized in the checklists below.

The intent of the checklists below is to list the tasks and workflow order that an architect needs to consider during contract administration. These items should be considered for each project, with refinements added.

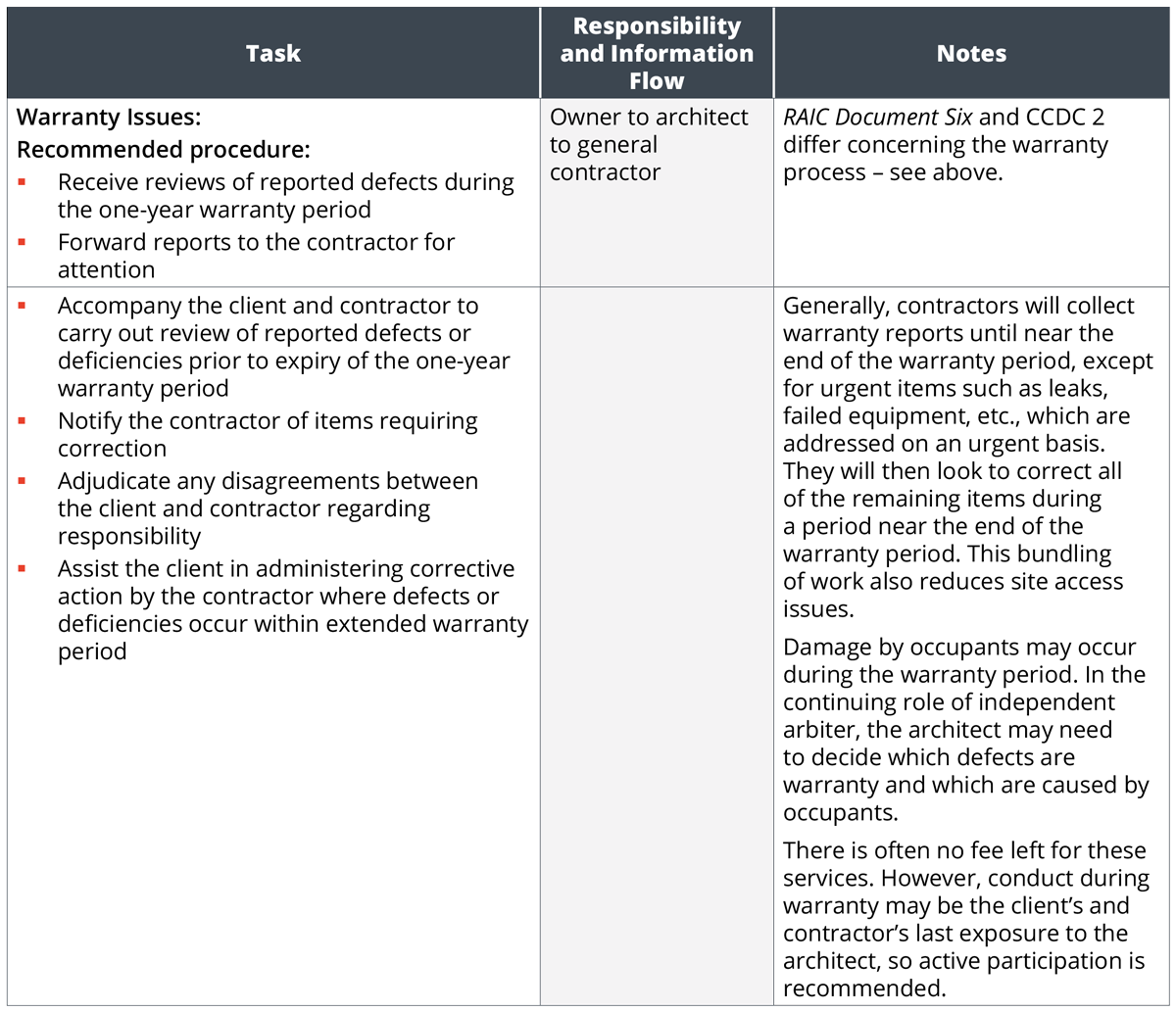

The checklists in this section are presented in a table format intended for use as a project diary in which to record observations. They are based on the client-architect agreement RAIC Document Six and CCDC 2 – Stipulated Price Contract, neither with supplementary conditions. The tables are intended to support the reader in developing their own comprehensive lists of items to support construction contract administration. They cannot be considered comprehensive or include all issues that may arise in projects. Projects vary in building types, complexity, project delivery method and scale. The reader is advised to consider these tables as templates in developing their own project diaries.

Supplementary conditions may be added to either/both the client-architect and client-contractor agreement. The architect should review both agreements before commencing contract administration activities.

Checklists for contract administration have been organized into the following stages:

- prior to construction:

- getting started – review of agreements;

- pre-construction contract administration activities;

- during construction;

- general communication requirements and procedures during contract administration:

- requests for information;

- supplemental instructions;

- contract change management;

- close-out services;

- during the warranty period.

Prior to Construction

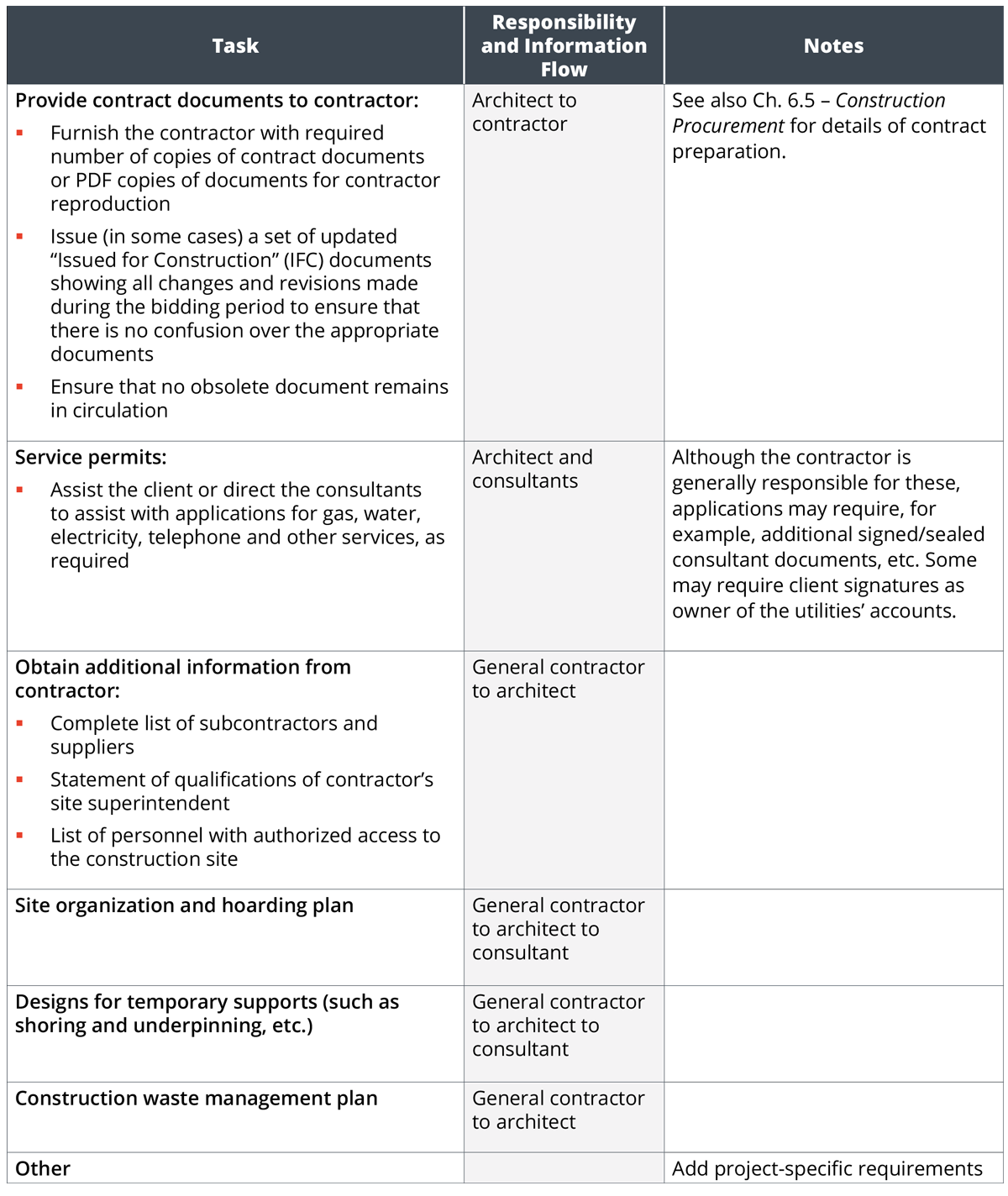

During the period after a contract between the client and contractor has been signed but construction has not yet started, there are some activities that the contract administrator needs to perform. Often the challenge of contract administration is assigned to a member of the architect’s staff who may not have been involved in the project until this phase. Before starting contract administration services, in addition to becoming familiar with the construction documents, the newly assigned contract administrator should familiarize themselves with the contractual obligations and roles of all parties through reviews of both client-architect and client-contractor agreements.

Getting Started – Review of Agreements

Two significant milestones early in the construction project are the signing of the client-contractor agreement and the start of construction. There are multiple activities that need to be completed prior to the achievement of these milestones. The order of interrelated activities may vary, based on the specifics of the project and the policies and practices of the client, contractor and architect. For example, there may be a desire to convene the pre-construction meeting shortly after the construction contract is awarded. During this meeting there may be a review of the pre-construction and pre-contract signing submittals. Alternatively, the pre-construction meeting may be convened after the pre-construction submittals have been received from the contractor and reviewed by the architect and client.

The tables below assume that a pre-construction meeting is convened before the submission required for these two early milestones.

Pre-construction Contract Administration Activities

The following activities should be undertaken prior to mobilization and within time frames specified in the contract documents.

During Construction

The standard stipulated-sum construction contract (such as CCDC 2) and the client-architect agreement (such as RAIC Document Six), in summary, require the architect to:

- review shop drawings, samples, and product data submittals;

- provide timely interpretation of the contract by responding to requests for information and issuing supplemental instructions;

- prepare and issue proposed change forms in a timely manner;

- review the contractor’s quotations prepared in response to:

- proposed changes;

- claims for additional costs initiated by the contractor;

- prepare and issue:

- change directives if the adjustments to the contract price and time have not been agreed upon;

- change orders once the adjustments to the contract price and time have been agreed to;

- review progress payment requests, usually on a monthly basis, in order to:

- monitor progress of construction against the contractor’s schedule;

- compare the contractor’s schedule of values with the actual work performed;

- verify receipt of statutory declarations and certificates from the respective provincial or territorial health and safety agencies such as Workplace Safety and Insurance Board or Workers Compensation Board for the second and subsequent submissions;

- prepare a Certificate for Payment and necessary documentation for progressive release of holdbacks and forward to the owner;

- prepare and distribute field review reports;

- prepare agenda for special site meetings.

General Communication Requirements and Procedures During Contract Administration

Certain procedures need to be considered throughout the period of contract administration (CA). These are basic elements of CA. The checklists below include some of these considerations.

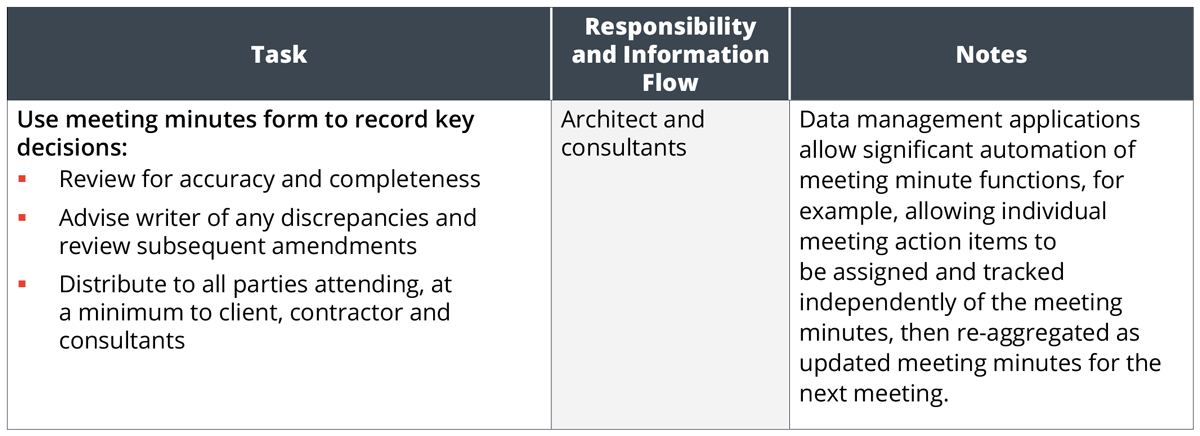

Minutes or Records of Meetings

The architect usually attends many meetings throughout the course of a project, and it is important that key decisions be recorded.

Minutes should be reviewed for accuracy and completeness, and minutes, together with any amendments, should be distributed to all parties.

See Chapter 6.8 – Sample Templates for the Management of the Project for a form and example of “Minutes of Meeting.”

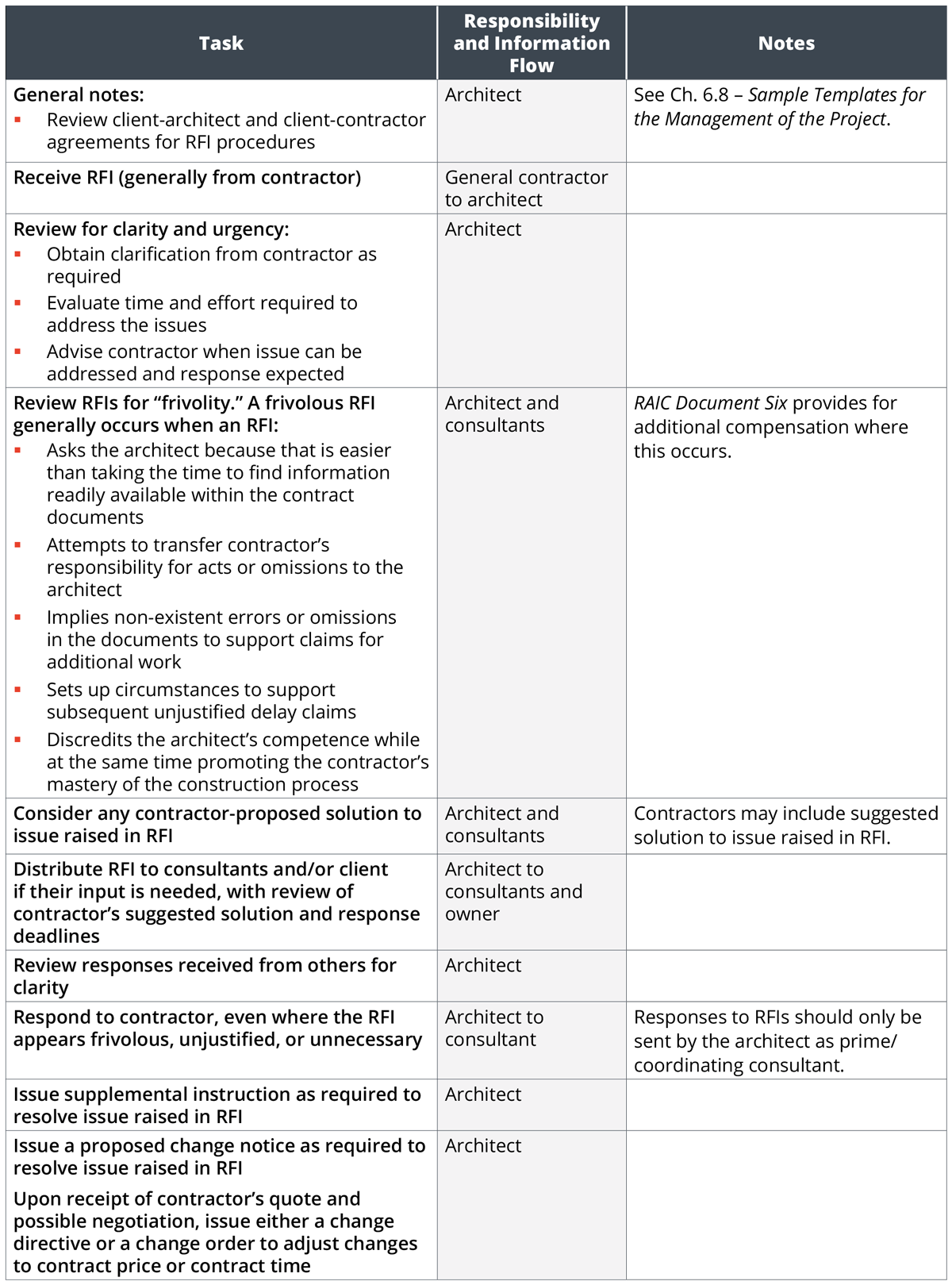

Requests for Information (RFIs)

A Request for information (RFI) is useful throughout the design and construction of a building project as a tool for the owner, architect, contractor or other party to request information from each other that cannot readily be obtained through research, document review, or other reasonable means. During the construction phase of a project, the general contractor, who is unable to find the information through review of the contract documents, often seeks information from the architect or the architect’s consultants. The RFI is a procedure for the contractor to request clarifications when the intent of the contract documents is:

- unclear;

- incorrect;

- missing information.

Each RFI should be tracked and resolved to completion and closure.

RFIs can contribute significantly to the smooth progress of construction, particularly when they are submitted well in advance, giving the architect and consultants time to clarify or correct a potential problem before it becomes a matter that could delay the progress of the work.

In all cases, it is the responsibility of the architect to provide the information or answer, with input from consultants when appropriate, either by issuing a supplemental instruction if there is no change to the contract price or contract time or, if changes are necessary, by initiating a proposed change, followed by either a change directive or a change order.

Some contractors abuse the RFI process by issuing an excessive number of unnecessary or “frivolous” RFIs. There are several possible reasons for this:

- asking the architect is easier than taking the time to find information readily available within the contract documents;

- to attempt to transfer to the architect the contractor’s responsibility for acts or omissions (refer to the General Conditions of RAIC Documents Six, 2018;

- to imply non-existent errors or omissions in the documents to support claims for additional work;

- to set up circumstances to support subsequent unjustified delay claims; or

- to discredit the architect’s competence while, at the same time, promoting the contractor’s mastery of the construction process.

The prudent architect ensures that the client/architect agreement includes provisions for appropriate compensation by the client for additional work related to:

- changes to the contract price or contract time resulting from RFIs;

- changes in scope initiated by the client.

Whatever the reason for the request, the architect is obliged to respond to every RFI, however frivolous, unjustified, or unnecessary. As a result, the architect must commit a significant amount of time and effort in answering unnecessary RFIs, for which there is no established means of being compensated. It is not reasonable that the architect should have to absorb the related costs if a contractor consistently abuses the RFI process, but it would also not be reasonable to expect the client to bear costs resulting from such unacceptable behaviour by the contractor.

In order to ensure that the architect will be reimbursed for the expenses of responding to unnecessary RFIs issued by the contractor, consideration should be given to adding the following supplemental condition to the CCDC2 or other construction contract form, revising the general condition regarding withholding of payment to state:

- the architect may determine that certain RFIs issued by the contractor are unnecessary and shall, in responding to such unnecessary RFIs, give the reasons for the determination in each case;

- if the contractor continues to issue unnecessary RFIs, the architect, after having identified a minimum of [insert number here (five)] RFIs as unnecessary, will invoice the client for the additional administrative cost of responding to each of the subsequent unnecessary RFIs;

- the architect will notify the contractor and the client each time such an additional administrative cost is charged;

- the client shall reimburse the architect for the monthly total of such additional administrative costs;

- the monthly total of such additional administrative costs shall be charged to the contractor by showing the monthly total as a credit on each subsequent Certificate for Payment. This constitutes a change to the contract price and must be handled as a change order.

For a sample RFI form, refer to Chapter 6.8 – Sample Templates for the Management of the Project.

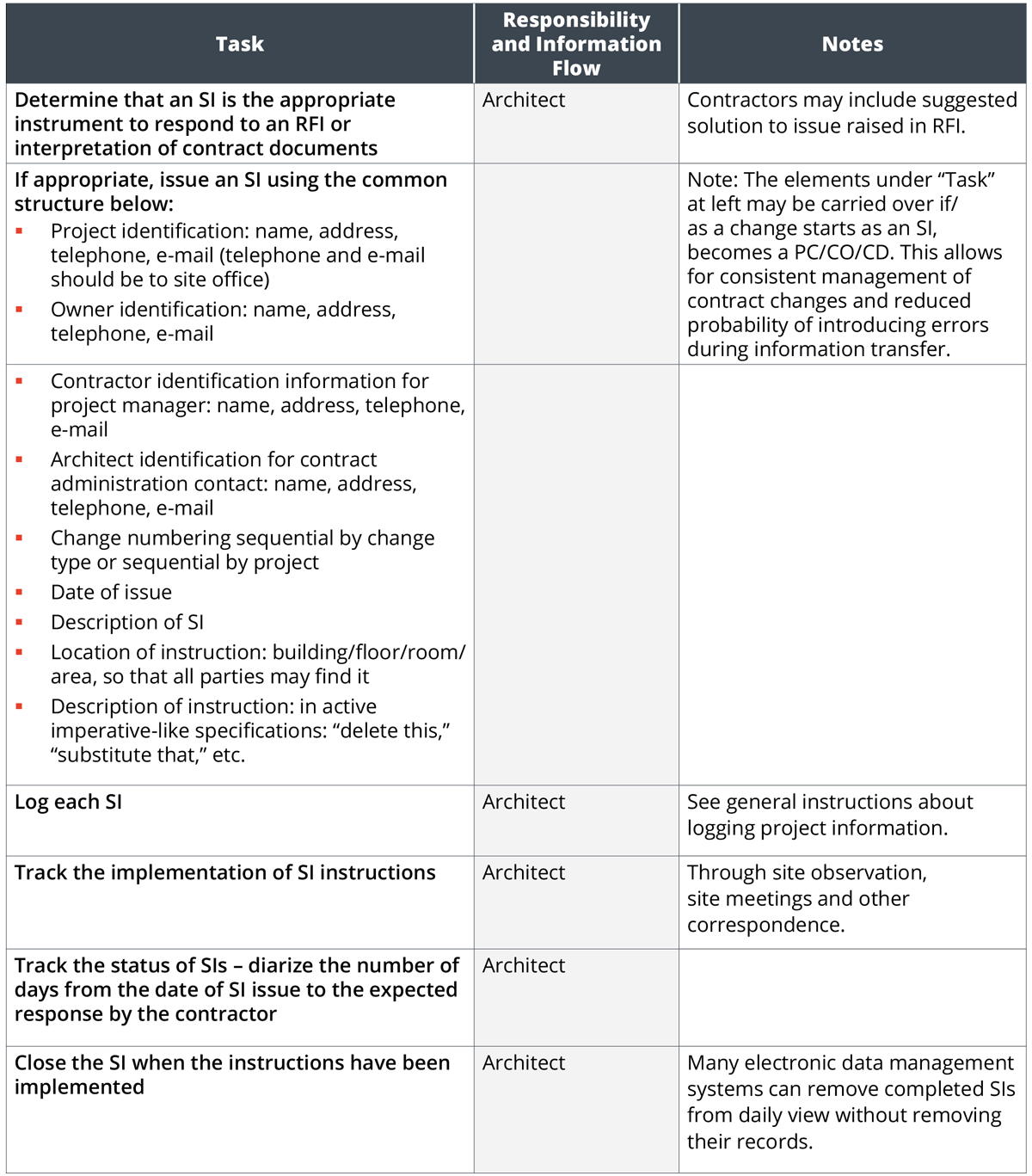

Supplemental Instructions (SI)

Supplemental instructions (SI), also referred to as site instructions, are issued in response to requests for information (RFIs) or to address issues raised on site or during a project meeting as clarifications or interpretations of contract documents. They provide direction to the contractor concerning a problem which may have surfaced during the course of construction.

If an SI involves changes to the contract price or to the contract time, the architect then issues a contemplated change notice or proposed change notice followed by a change order or change directive.

Refer also to CCDC 24 – 2016 – A Guide to Model Forms and Support Documents (for use with CCDC 2) for the information to be contained in a supplemental instruction and for a sample form.

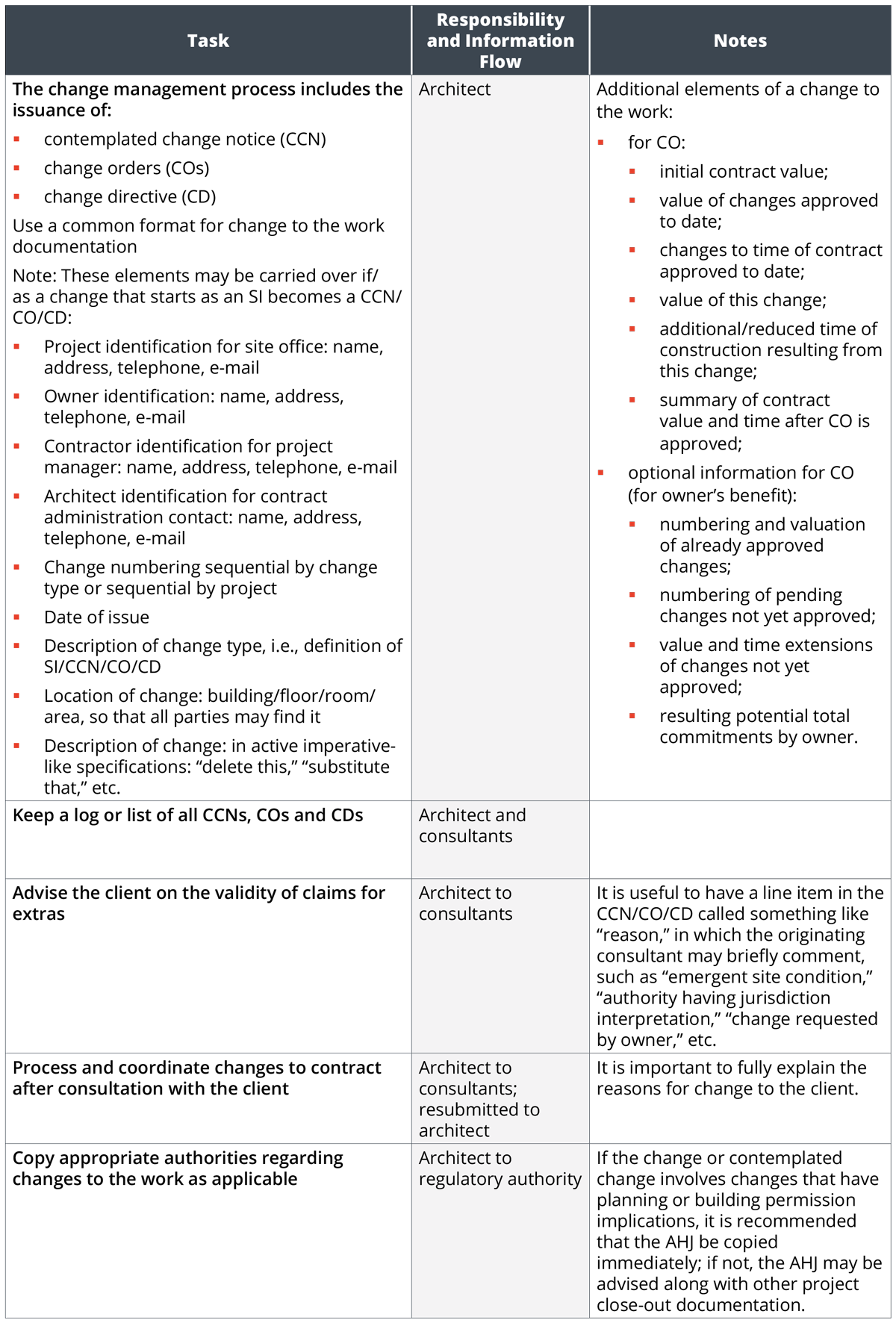

Contract Changes Management

The change management process ensures that changes to the construction contract price and schedule are reviewed, analyzed and approved. The process includes the issuance of the instruments of service called:

- contemplated change notice (CCN), also called a proposed change notice (PCN);

- change orders (CO);

- change directives (CD).

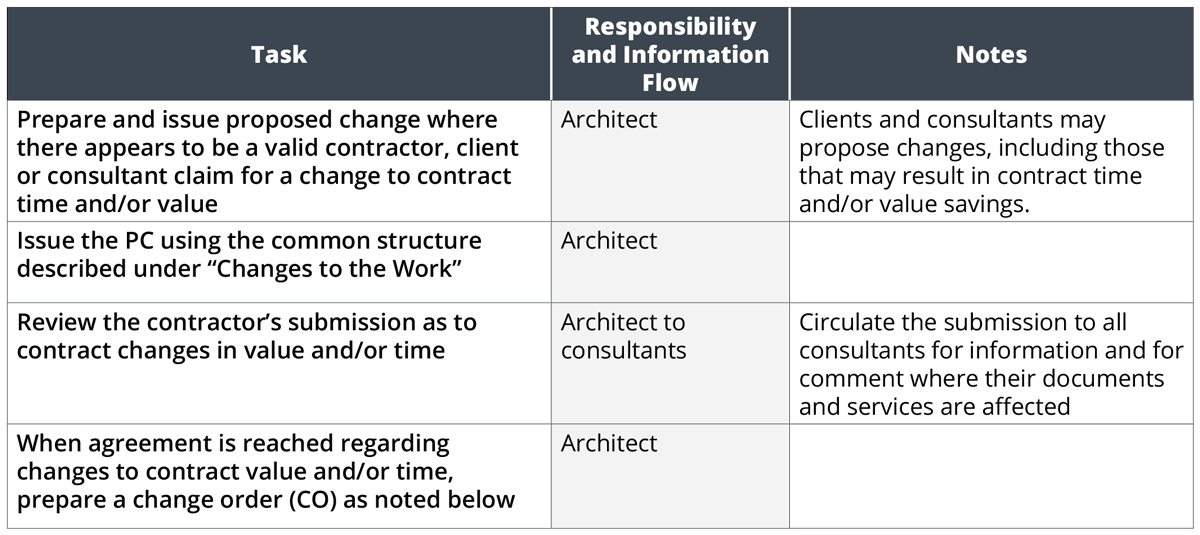

Proposed Change (PC)

The process is usually started by the issuance of a form known by one of the following terms:

- proposed change;

- contemplated change notice;

- proposed change notice;

- notice of change;

- contemplated change order;

- change notice.

CCDC recommends the term “proposed change” (PC). The purpose of the PC form is to alert the contractor to the proposed change and to provide the contractor an opportunity to submit a quotation for additional cost (or credit) and/or a change in schedule (if any) for the proposed change. PCs are issued when the contractor indicates, and the architect agrees, that a proposed change involves a change to contract price or contract time.

When the need for a change occurs, the architect (and/or the appropriate consultant) prepares and issues to the contractor written and graphic documents, as necessary, to describe the proposed change or a notice of a change being contemplated. Although CCDC recommends the term “proposed change,” many architects use the term “contemplated change.”

Sometimes a contractor will claim that a clarification or interpretation in a supplemental instruction is a change. If a supplemental instruction identifies work that is deemed to be a change in price and/or time, the architect should obtain a quotation for the changes from the contractor. If the contractor’s quotation is accepted, a proposed change is issued, assigned the next consecutive proposed change number, and entered on the Summary of Changes Form.

As documents are prepared, the architect must forward copies to the owner, contractor, and relevant consultants with any necessary covering letters or explanation.

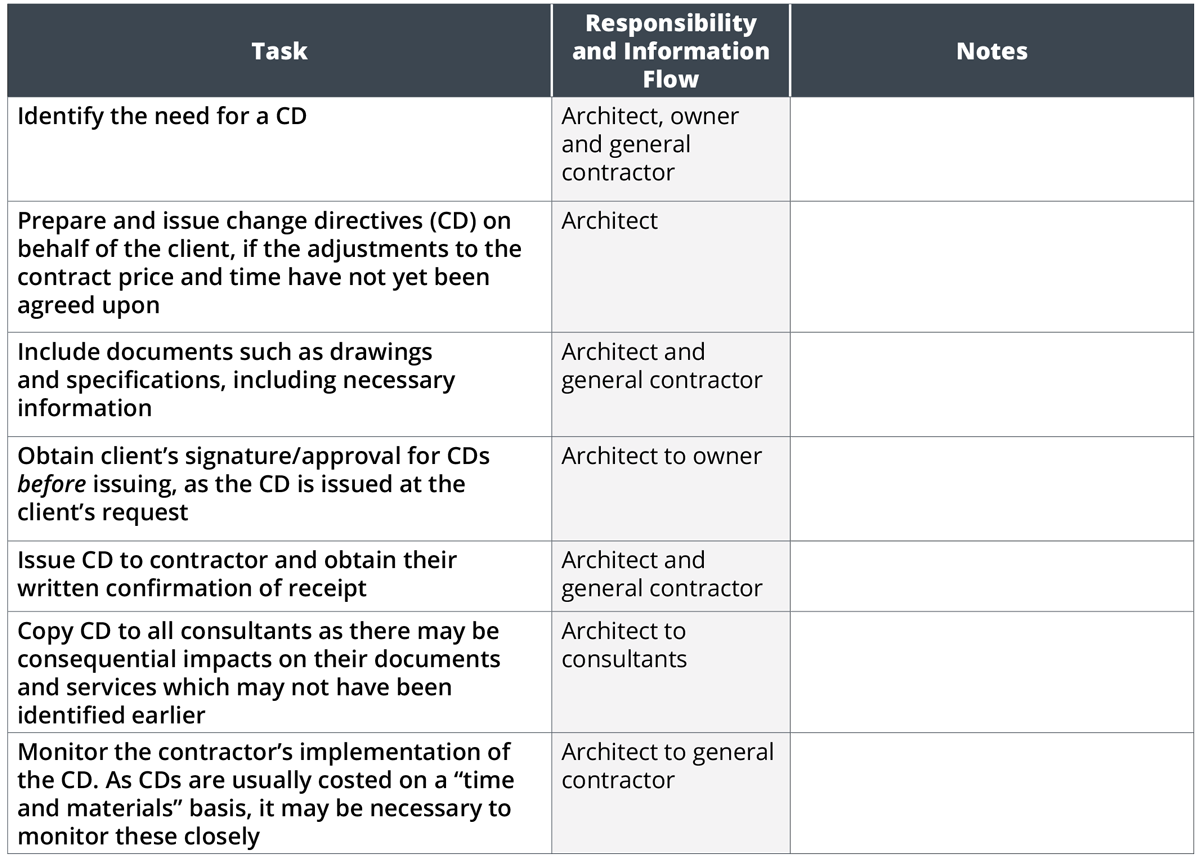

Change Directives (CDs)

If the contractor’s price cannot promptly be agreed to, the architect may issue on behalf of the owner a change directive if the proposed changes are within the general scope of work described in the contract documents. A change directive avoids delays and permits work to proceed while negotiations continue over the price of the proposed change. A change directive may be issued to the contractor without a preceding proposed change when, for example, it is urgent that a change be authorized to proceed immediately without waiting for a quotation from the contractor. In these circumstances, the change directive is the initial document and therefore must include the detailed statement of the work required which is normally provided in a proposed change.

The change directive form may be like the SI or PC form – not the CO, as there has been no determination about cost or time changes to the contract.

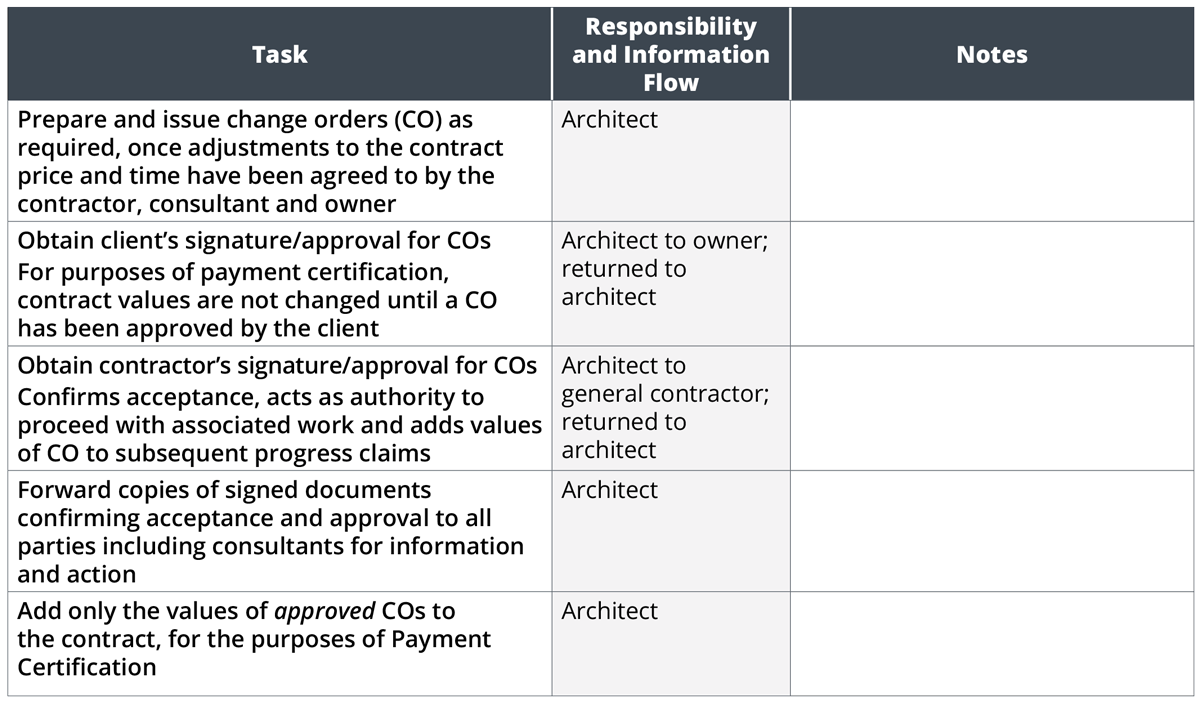

Change Orders (COs)

COs cover adjustments to the scope of work that require changes to the contract price and/or contract time. They are prepared after acceptance of changes to contract time and/or value as proposed by the contractor, arising from the proposed change or change directive procedures. The CO is also used to confirm charges or adjustments to contingency or cash allowances in the contract.

The change order is the final form which indicates the agreement between the client/owner and the contractor on specific additions, deletions, or revisions to the contract documents. COs may arise from:

- additional requirements or changes in the requirements made by the client/owner;

- new or different interpretation of requirements by authorities having jurisdiction;

- work not described in the contract documents, such as emergent site conditions (boulders, artesian wells, etc.);

- work inaccurately or incorrectly described in the contract documents;

- substitutions which may affect the contract time or contract price.

Summary of Changes

When a proposed change is initiated, it should be entered immediately on a Summary of Changes Form or into the construction contract administration database used to track the status of all changes. This document is an important tool for the architect to manage a process which can become chaotic if it is not closely monitored.

Tracking and tabulating all proposed changes, change directives and change orders is important for three reasons:

- to manage a process which can become chaotic if it is not monitored;

- to establish the revised contract price (and time);

- to process Certificates for Payment.

Typically, all change orders are listed on a table or chart identifying all credits, extras and the adjusted contract price.

Refer to CCDC 24 – A Guide to Model Forms and Support Documents (for use with CCDC 2) for the information to be contained in a “Proposed Change,” a “Change Order,” and a “Summary of Changes,” and for sample forms.

Numbering and Cross-Referencing Documents

It is common for architectural practices to employ database systems for monitoring and controlling construction contract administration. These systems are now available and affordable as stand-alone, server-based, or web-based applications. Numbering, tracking and cross-referencing of construction contract administration documents using these systems is automated. However, firms may use a stand-alone application, such as a spreadsheet, to manually manage construction contract administration processes and documentation.

There are two methods used by architects for assigning numbers and recording changes. If manually managing contract administration documents, the architect should use the selected method consistently:

- The first method involves assigning consecutive numbers to each document in the change process as they are prepared, using a separate numbering sequence for each document type (separate numbering for supplemental instruction, proposed change, change directive, and change order) and entering the number on the Summary of Changes Form. Since the timing of the change process is unpredictable, some architects believe it is not practical to attempt to retain the same number for each of the successive documents dealing with a specific change. Instead, referencing the number(s) of the preceding document(s) is done to assist in tracking the change process. For example, the first line of the change directive 10 could be “Refer to Proposed Change 6 and Change Directive 10.” Often grouping proposed changes to form a single change order makes sense in balancing credits and extras, and this may be better received. Approved change orders are consecutively numbered to avoid gaps when a proposed change does not proceed beyond pricing.

- Many architects and large clients prefer to create a separate file and number for each document type in the change process and to keep the same number assigned to the change throughout the approval process. It is simple and easy to track each change with its own unique number and this avoids incorporating several proposed changes under one change order (for example, proposed change no. 8 automatically becomes change order no. 8). If a proposed change is abandoned, it is simply recorded as cancelled and the number remains. This makes tracking of the process easy. Again, the Summary of Changes Form should be completed immediately recording all changes.

In addition to start-up, informational and change-related activities, there are many contract administration procedures occurring during construction. Some occur regularly, others periodically, and some on only one or a few occasions.

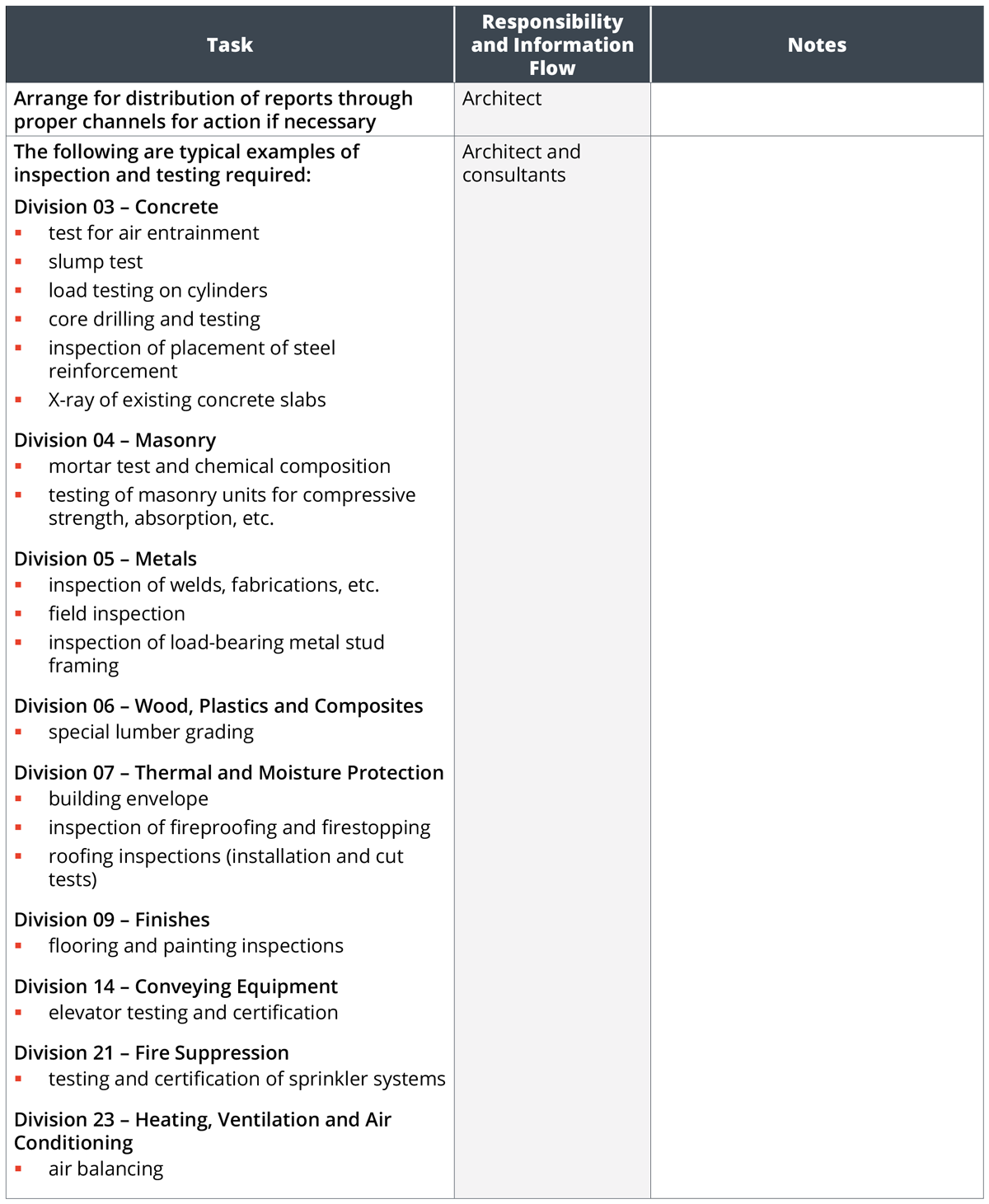

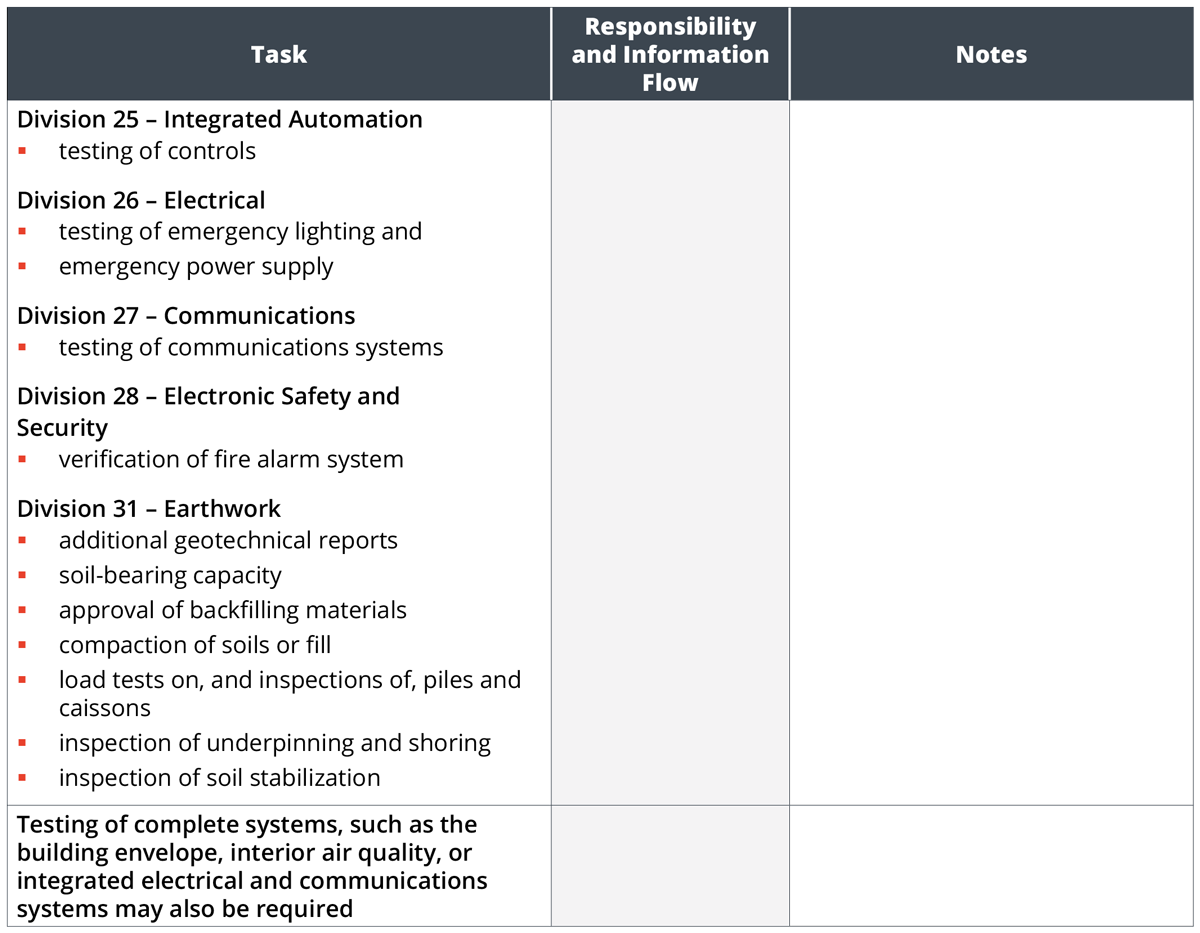

Inspection and Testing

Independent inspection provided by specialist inspection and testing firms is required on most construction projects. The following summarizes the relationship of these specialists with the architect:

- inspection and testing are usually recommended by the architect or the engineers;

- inspection and testing may be asked for in the contract document (specification and drawings);

- these specialists do not supersede the architect’s authority;

- the architect must ensure that they are only assisting in the process and not assuming a contractual obligation;

- inspection and testing firms undertake tests and issue timely reports, but they do not interpret the results of these tests or issue instructions to the contractor;

- interpretations are made by the contractor in the first instance and finally by the architect and the engineering consultants.

Inspection and testing firms are frequently selected by methods typically used for selecting other professionals, that is, by soliciting proposals. The cost of these services is generally paid by the owner:

- directly to the inspection agency; or

- indirectly through the general contractor.

Inspection and testing services are frequently paid through cash allowances provided for in the construction contract. Sometimes, inspection and testing services are included as a subcontract. For example, air balancing is frequently a subcontract of the mechanical contractor. Also, manufacturers’ representatives, such as certain roofing membrane manufacturers, commonly inspect the installation of their products by the trades to ensure compliance with their standards.

Establish with the contractor the requirements for testing and inspection of specific materials and work by inspection and testing companies.

These services are ancillary to the architect’s basic construction administration services.

Submittal Review

Contract documents, and in particular specifications, identify many elements of construction and provide lists of pre-approved products and systems. For example, specifications may indicate that the products of any of four flooring manufacturers, three elevator companies, six roofing suppliers, etc., are acceptable. In addition, within each pre-approved manufacturer’s products are specific product types as well as different colours, textures, etc. The submittal review is used to identify the actual combination of pre-approved systems, products and their characteristics that will be incorporated into the construction.

At the initial pre-construction meeting with the contractor, the architect usually establishes the standard procedures for submittal and review of shop drawings, samples and mock-ups. Before submitting submissions to the architect for review, the contractor is responsible for verifying:

- quantities;

- dimensions;

- accuracy;

- completeness;

- compliance with the specifications.

Shop Drawings

The submission requirements and the format for shop drawings should be contained in the specifications. Certain shop drawings must be reviewed by the consultants. Shop drawings do not supersede the contract documents but supplement them to assist in the construction.

The review of shop drawings carries certain liabilities for the architect. The architect must take care to review only those portions of the shop drawings which relate to the architectural design. The consultants and engineers are responsible for reviewing their part of the design. The precise wording of the cover letter and application of notations to shop drawings is important. Review submittals as described in specifications. Submittals are never intended to supersede or change the contract documents.

It is also important to ensure the timely review and tracking of all shop drawings.

Samples

Samples provide the architect with an opportunity to review and finalize selection of patterns and other specified colours, textures, etc., and to confirm specific design and aesthetic intentions prior to ordering a product. The architect may wish to be pro-active and request early submissions of all samples to avoid any impact on the price or delivery of the finish or material.

Hierarchy to Submittal Review

There is a recommended hierarchy to submittal review. If requested in the specifications, some items are reviewed first, then following in a specific order. This results in a more efficient review process. The recommended sequence for submittals is:

- System performance – supporting documents to demonstrate that the proposed system will meet the required performance levels in the contract documents, e.g., curtain wall, roofing systems, firestop systems.

- Product data – also known as catalogue cuts, are technical product literature found in systems or used as a stand-alone item for use on site. Product literatures are to identify:

- the removal of irrelevant information;

- the make and model of selected items;

- colour selection;

- available features and options;

- technical properties (if not submitted prior under a system).

- Shop drawings – project and site-specific illustrations depicting how the contractor intends to manufacture and assemble the system or assembly. They ensure and confirm the accuracy, size, and other specific data about a product or material prior to final purchase, fabrication or delivery. Shop drawings are prepared to indicate:

- accurate dimensions, size, quantity and location;

- precise fabrication methods;

- construction and/or field erection techniques;

- information to coordinate related trades or adjacent work;

- elaboration on diagrammatic information;

- confirmation of the selection of options, such as colour or finish.

- Samples provide the architect with an opportunity to review and finalize selection of patterns and other specified colours, textures, etc., and to confirm specific design and aesthetic intentions prior to ordering a product. They also act as a control sample, setting the example for quality of material used on site. The architect may wish to be pro-active and request that the contractor expedite early submissions of samples if final design and selections still need to be made. All samples are to avoid any impact on the price or delivery of the finish or material.

- Mock-ups are the contractor’s attempt at putting together the system, including all its components and products, demonstrating how it will be assembled in situ. Architects need to have all the previous submittals reviewed and accepted to perform the examination on site mock-ups. Final acceptance then becomes the expected standard for quality and workmanship throughout the project for that item.

See Chapter 6.8 – Sample Templates for the Management of the Project for suggested use and wording of shop drawing cover letters and notation stamps.

Construction Site Meetings

Contractors generally have many internal meetings associated with the progress of a construction project.

One of the architect’s responsibilities during construction is to participate in job-site meetings. The architect should be familiar with the progress of the job prior to any regularly scheduled job meeting. Regularly scheduled site meetings are essential to:

- communicate the client’s expectations to the construction team;

- ensure good communication between all parties;

- exchange and transmit technical information such as shop drawings;

- provide a structured opportunity for field review;

- resolve problems and discuss all relevant design and construction issues;

- assist in making judgements and determinations;

- review schedules and progress claims.

Site meetings provide an excellent opportunity for the architect to establish an on-site presence. Minutes of the site meetings should always be recorded. They should indicate what actions are required and who is responsible for the action. Minutes should be distributed within 48 hours of the meeting. Either the architect or the general contractor prepares the minutes, depending on the architect’s choice and the general requirements of the specifications.

Those generally involving the architect are noted below.

General Review

There are many types of general review as noted below, including:

- Periodic general review, the most typical review by the architect and consultants;

- On-site or off-site, as described below;

- Milestone reviews, scheduled around specified events such as start-up or completion of a trade’s work or phase of work;

- Mock-up review, which has specific characteristics noted below;

- Partial occupancy review, where the client or contractor requests that one or more portions of the completed project be occupied earlier than complete substantial performance;

- Substantial performance review when requested by the contractor near the end of a project;

- Completion review when final deficiencies have been completed;

- Warranty review during or near the end of the warranty period.

General reviews typically occur in one of three locations:

- The construction site – the location identified in the contract documents where the building is situated is called the “Place of the Work” in CCDC documents. This is where most of the construction activities take place and where the architect will conduct most of the site reviews, unless the building is prefabricated off-site.

- The “extended” site – a location where products may be stored away from the construction site. The value of major items delivered to an off-site location may be considered eligible for payment, subject to the terms of the contract or once the following conditions have been met:

- after approval that the products may be located away from the construction site;

- after the contractor has made provision for secure storage, insurance and bonding;

- after the architect has visited the extended site to observe the items there.

- Plant or off-site locations – work which is fabricated or assembled in a plant. The architect or consultants observe work in the plant to:

- examine the manufacturing facilities and capabilities of the subcontractors before a contract is awarded;

- confirm progress of items in those locations;

- check or confirm progress of items, such as:

- items whose schedule for delivery is critical to the progress of the project;

- items which come to the construction site pre-assembled and could not be properly reviewed after delivery;

- resolve problems noted by inspection and testing companies, such as:

- truss welding details;

- prefabricated wall panel details;

- resolve manufacturing problems concerning details which prove to be impractical, such as:

- the size of metal breaks;

- prefabricated wall panels;

- witness tests undertaken in the plant, such as:

- tests for curtain wall mock-ups;

- tests on specialized prefabricated roof structures;

- tests of air diffusers;

- review mock-ups, such as:

- elevator cabs;

- special ceiling systems;

- determine the source of problems occurring in the field which can be traced to plant manufacture or fabrication, such as:

- welding deficiencies;

- efflorescence.

The architect should establish credibility on the job site from the start of the project. This is accomplished through a detailed knowledge and understanding of the project and the contract documents. The architect must conduct reviews systematically. Upon completion of a field review, the architect should prepare written reports for the owner and the contractor and, when required, for building officials. Site observations should be consistent, responding to the stage, progress, and quality of the work.

Some architects bring reduced-size sets of drawings to the site. These are very useful for comparing observed work with the contract documents. Other required or important tools to bring onsite are:

- hard hat and safety boots;

- camera (preferably with a time and date record);

- voice recorder and/or note pad;

- safety glasses;

- safety vest;

- tape measure.

Depending on the project it may be useful to provide a variety of other tools.

Upon arrival at the site, the architect should either:

- talk to the site superintendent or leave a note for the superintendent; or

- contact the contractor’s other site personnel.

A site visit can include:

- a quick overview, to get a general impression of the progress of the work relative to the schedule and to the last site visit;

- a tour with the contractor and/or owner to understand their problems and concerns;

- a tour with the general contractor and a single subcontractor to concentrate on key trades in progress at the time.

The architect should not leave the site without speaking with the site superintendent or the contractor. Observations should be reported to the contractor’s superintendent at the conclusion of the visit to indicate to the superintendent any problems which have been noted.

The architect should endeavour to promote good communication and a close working relationship at all times with the contractor. However, if it is not possible to resolve on-site problems, the architect should ensure that the deficiencies are recorded in a field review report. Refer to Appendix G – Checklist – Items for General Review at the end of this chapter, and to the many published checklists for:

- items to review during site visits;

- construction administration services.

Frequency and Timing of Site Visits

The architect should schedule site visits at intervals appropriate to the construction. The frequency and timing is left to the judgement of the architect. Visits should be conducted at different times of the day and on different days of the week. This prevents familiarity with the architect’s routine and the scheduling of some construction when it might not be readily observed. In addition, it may be necessary to make strategically timed site visits to deter the contractor from becoming complacent about any contractual obligations.

Before processing progress claim applications, the architect must also visit the site and make detailed observations to determine:

- the percentage of work completed;

- the amount of materials stored on site (or on the “extended site”).

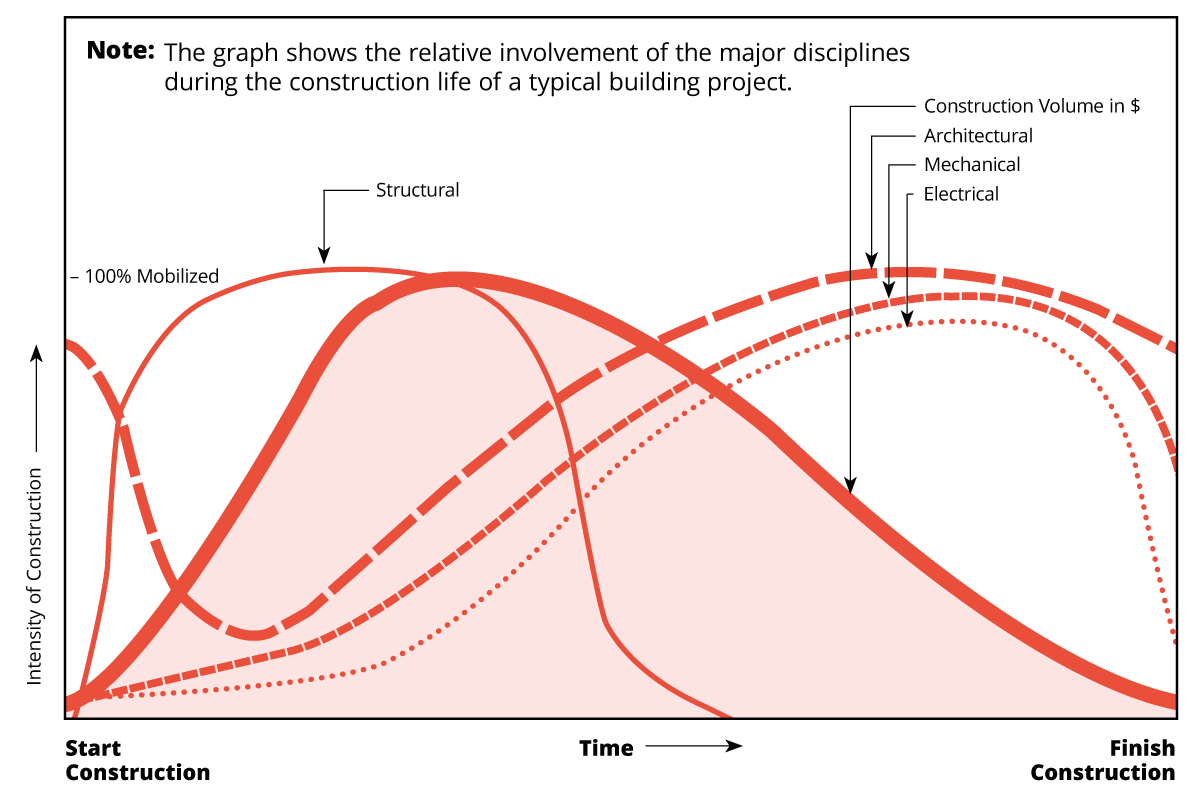

Usually, more visits are required at the start-up and close-out of construction as noted in Figure 1. Structural engineering review is more intense at the early stages of a project, whereas mechanical and electrical consultants are more involved near the completion of construction.

The following are general guidelines on when to conduct field reviews:

- at project start-up and/or excavation;

- at the start of major subcontractors’ work on elements forming the enclosure of the building, such as:

- forming and framing;

- structural steel;

- masonry;

- waterproofing;

- cladding;

- window systems;

- roofing;

- at the start of finishing trades, such as:

- floor finishes;

- cabinetwork;

- wall finishes;

- painting;

- when significant new materials and equipment are delivered to the site.

Because many types of work (masonry, for instance) cannot be corrected readily without replacement, timely field review is needed to preclude rejection of work which has been underway for several weeks.

Additional field reviews should be considered immediately before and during concrete placement to review:

- key dimensions;

- placement of reinforcing steel and inserts;

- presence of any debris, rust, water, etc., within formwork;

- placement of electrical and mechanical services;

- concrete placement.

When the work of one trade is covered up by another trade, it is too late for observation; therefore, field reviews must be done before the following work is covered up:

- insulation;

- fireproofing/firestopping;

- vapour barriers;

- blocking and furring;

- electrical and mechanical services.

Scheduling reviews before work is covered up allows for deficiencies to be corrected prior to permitting the completion of the remainder of the installation.

The architect usually conducts a field review after any serious or unexpected change in the weather, which can have an adverse effect on work in progress, to determine whether any damage has been done to existing work, such as:

- undermining or weakening of footings or foundations by heavy rain;

- freezing of concrete or mortar due to sudden drops in temperature;

- frost penetration of sub-soil;

- damage to roofing membranes and unbraced walls by strong winds;

- improper curing or drying out of materials from prolonged heat.

Finally, the architect may:

- carry out a detailed review before the owner takes early occupancy of any area, prior to completion of the entire project;

- prepare a deficiency list for the contractor and the owner before partial occupancy takes place.

FIGURE 1 Graph showing typical duration and intensity of work on site by discipline.

Reporting

The architect should write a report after every visit spent observing work in the field. The field review report may include the following information:

- name and position of the person conducting the field review;

- date, time, and duration of the visit;

- weather conditions, including any extreme conditions;

- names of those present or name of the site superintendent and the general contractor;

- percentage of work completed by trade;

- work progress compared to the contractor’s schedule;

- work now underway or being accomplished;

- work scheduled to be completed before next visit;

- questions raised by the contractor or the owner;

- determinations made by the architect;

- outstanding issues requiring action;

- the list of people receiving copies of the report;

- status of deficiencies or outstanding issues from previous report;

- the report number for filing purposes.

Refer also to Chapter 6.8, Sample Forms for the Management of the Project, for a sample form for a field review report.

Architects can take the checklist to the job site and use it to assist in recording observations and writing field review reports.

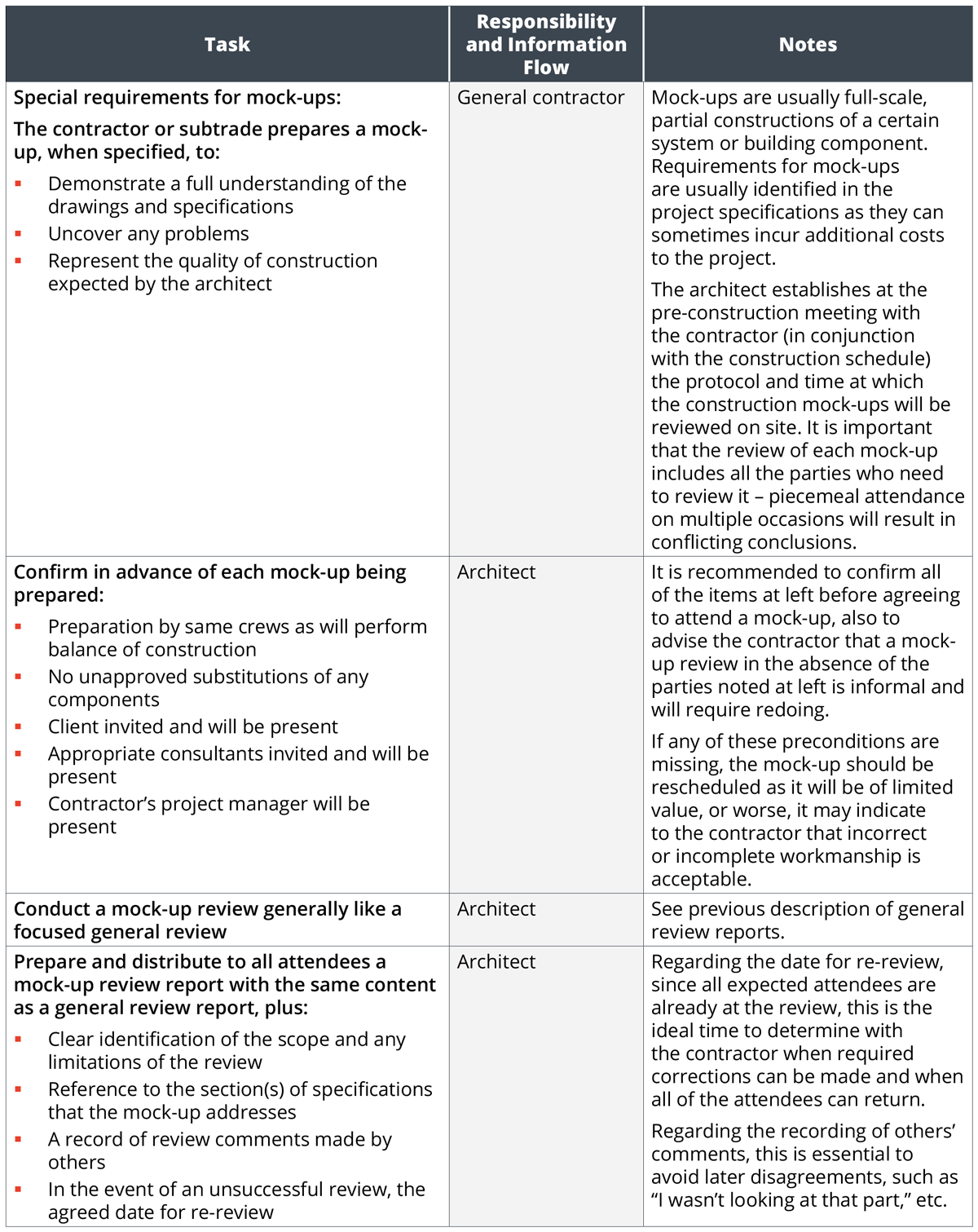

Mock-ups

Mock-ups are usually full-scale, partial constructions of a certain system or building component. The contractor or subtrade prepares a mock-up, when specified, to:

- demonstrate a full understanding of the drawings and specifications;

- uncover any problems;

- represent the quality of construction expected by the architect.

The architect should establish a schedule for construction of mock-ups and procedures for their review at a pre-construction meeting.

Mock-ups are often treated by contractors as a form of submittal. This may arise from the fact that much construction management software does not have separate mock-up “modules.” However, a mock-up is different than other submittals because:

- it involves multiple trades, products and systems rather than discrete submittals;

- the sequencing and interactions of these multiple trades and their work is a major part of the review process;

- it will likely serve as an ongoing identification of the expected quality standard for a portion of the project;

- all of the client, the architect and the affected consultants are required to review the mock-up at the same time and place.

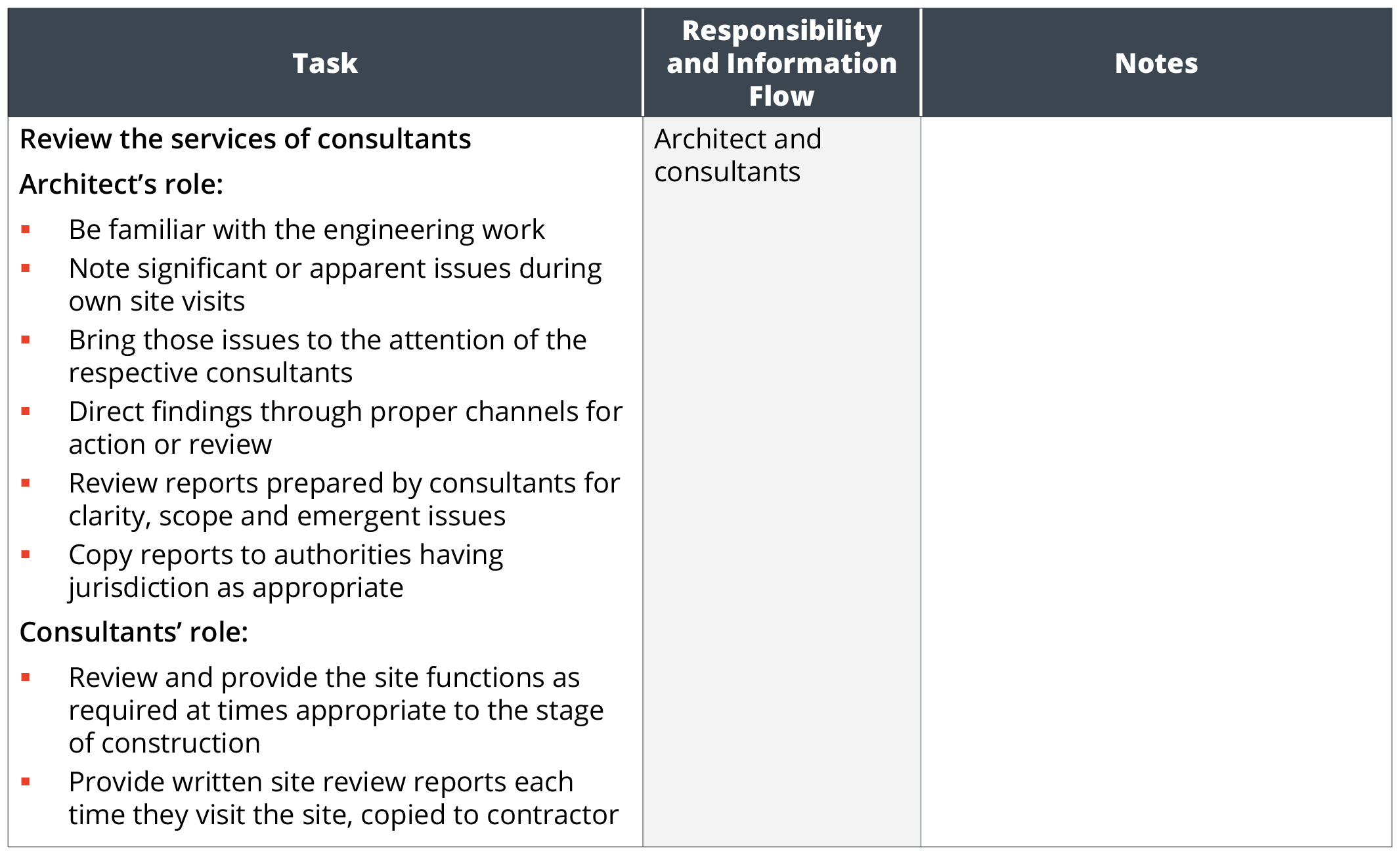

Field Review Services of Consultants

The architect is usually the prime or “managing and coordinating” consultant, and is responsible for coordinating the field functions of the engineering and other consultants. It is important to call upon the services of the consultants at the appropriate stages of construction. All consultants should be required to submit general review reports in a format like that used by the architect. The architect will distribute the reports as required. In addition, the architect relies on the consultants to determine the value or percentage of work completed by each respective discipline to prepare Certificates for Payment.

Some aspects of review by engineering consultants differ from that of the architect. For example, some engineering disciplines, especially mechanical and electrical, provide information in a more diagrammatic manner than is presented in typical architectural drawings. Therefore, the trade or subcontractor can use more discretion in the installation and operation of various equipment and systems. This diagrammatic information requires more interpretation on the part of both the engineer and the subcontractor.

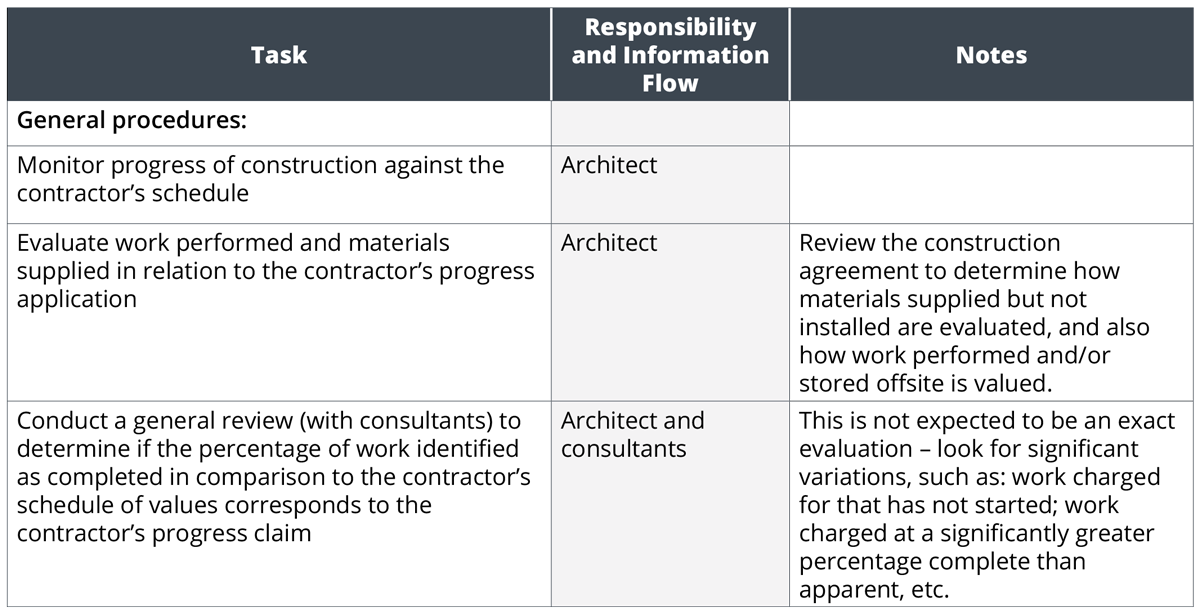

Certificates for Payment

In typical stipulated-sum construction contracts, the architect is responsible for preparing Certificates for Payment indicating when and how much a client must pay the contractor.

Certificates are based on:

- the schedule of values agreed to and prepared at the start of construction;

- the architect’s determination of the percentage of work completed, based on a general review;

- the applicable holdbacks required in the provincial or territorial lien legislation.

Architects may prefer to present more detail on the Certificate for Payment, rather than preparing a separate detailed summary each month for attachment to the Certificate. On separate lines in the contract summary section on the certificate itself, a summary of the status of change orders could list:

- the total price of changes issued previously;

- changes issued during the preceding month, each listed separately, showing:

- the change order number and the increase or decrease in the contract price;

- the net total of the current month’s issued change orders shown in the totals column.

Construction contracts frequently include a contingency allowance, against which the price of each change order is charged or credited. CCDC 24 – 2016 A Guide to Model Forms and Support Documents contains an example showing a method for reporting these charges when this type of contract is used.

Refer to CCDC 24 – A Guide to Model Forms and Support Documents (for use with CCDC 2) for the information to be contained in a “Certificate for Payment” and a “Schedule of Values” and for sample forms.

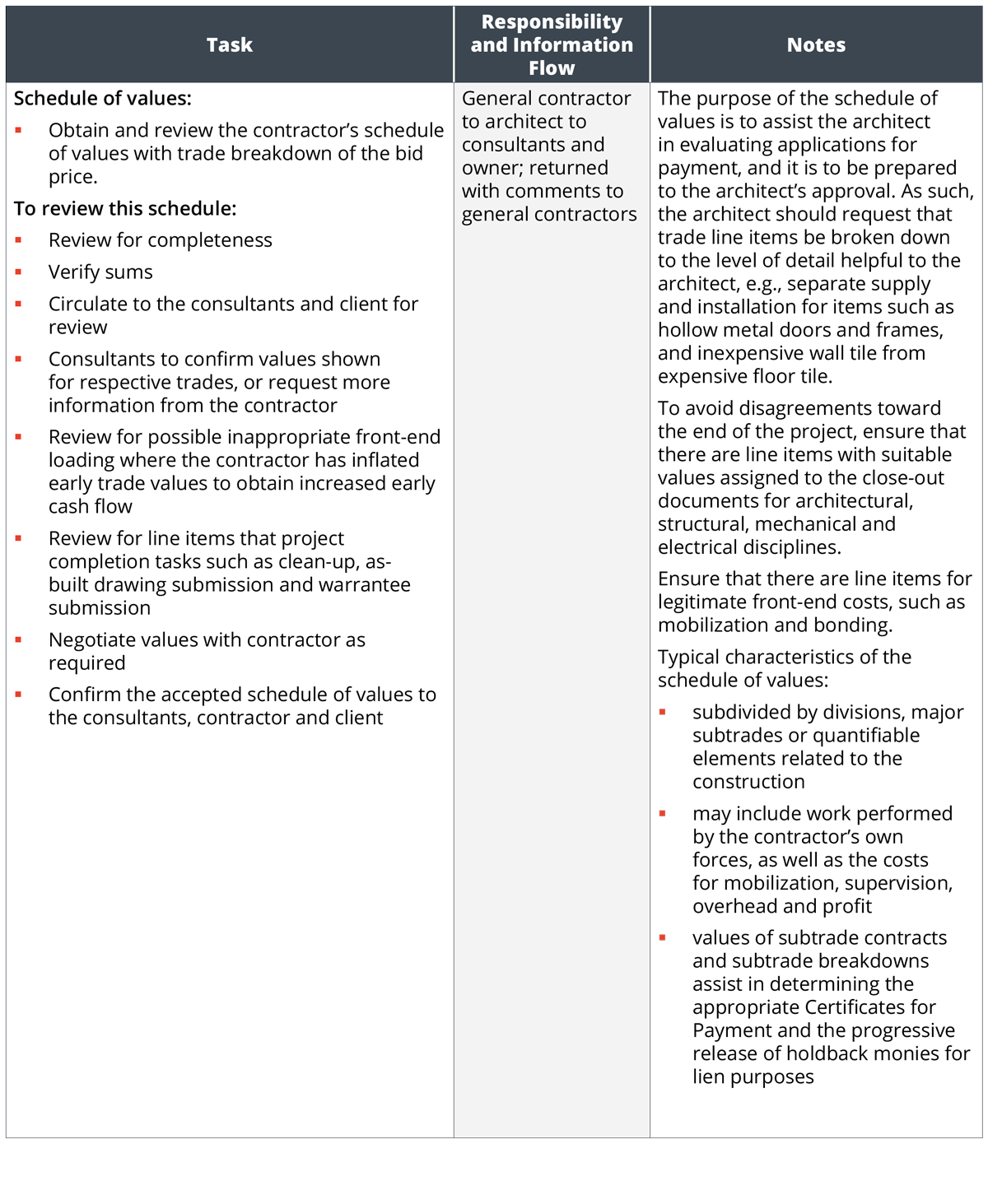

Schedule of Values

Usually the contractor submits a schedule of values at the start of the project. The schedule of values is typically subdivided by divisions, major subtrades, or quantifiable elements related to the construction. The work performed by the contractor’s own forces, as well as the costs for mobilization, supervision, overhead, and profit, are usually indicated. The value of subtrade contracts and subtrade breakdowns assists in determining the appropriate Certificates for Payment and the progressive release of holdback monies for lien purposes.

The architect should review the schedule of values for completeness and for an accurate and realistic distribution of cost. It can be compared with the most recent construction cost estimate to identify significant discrepancies.

Percentage of Work Complete

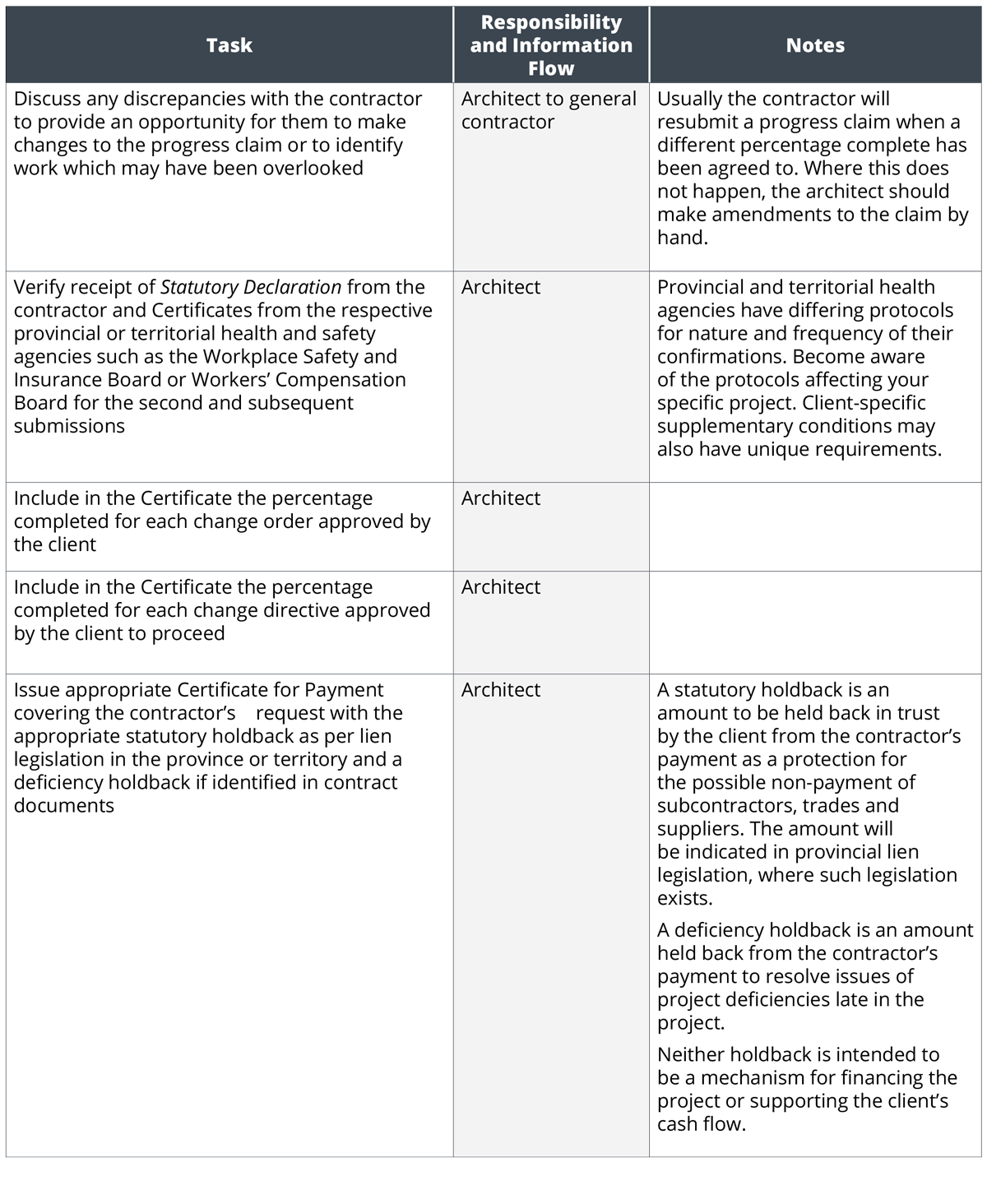

Payments to a contractor under a construction contract are usually made monthly in response to the contractor’s submission of a “progress claim”. The architect should conduct a field review to determine if the percentage corresponds with the contractor’s progress claim. Any discrepancies should be discussed with the contractor to provide an opportunity to make changes to the progress claim or to identify work which the architect may have overlooked. Assistance in determining the percentage completed of certain structural, mechanical, and electrical components will require a field review and advice from other members of the design consulting team. Once the architect has determined a representative percentage, a Certificate for Payment can be prepared.

Statutory Holdbacks

The architect prepares a Certificate for Payment based on the percentage of work complete and the contractor’s progress claim. Change orders must be accounted for in the Certificate for Payment, as well as the appropriate holdback required by the provincial or territorial lien legislation.

Refer to Chapter 6.7 – Take-over Procedures, Commissioning, and Post-occupancy Evaluations, Appendix A – Provincial and Territorial Lien Legislation for a list of the appropriate lien acts to determine the amount of holdback and requirements for release of holdback monies.

Recording Change Orders on Certificates for Payment

Each monthly Certificate for Payment states the current value of the contract in the section headed “Contract Summary” by adding the net total price of all changes agreed to up to the date of the Certificate for Payment, including:

- change orders issued; plus

- the current value of work under change directives certified.

The Contract Summary section in the model Certificate for Payment form in CCDC 24 proposes showing the net total price only of all change orders issued previously including the current month; there is no space for providing details of the change in price for each of the current changes. The Guideline to the Certificate for Payment Form in CCDC24 advises, however, that the method of presenting this information should be revised as necessary to suit the many variations in accounting used for this purpose.

Architects may prefer to present more detail on the Certificate for Payment, rather than preparing a separate detailed summary each month for attachment to the Certificate. For example, a summary of the status of change orders would list on separate lines in the Contract Summary section on the Certificate itself:

- The total price of changes issued previously;

- Changes issued during the preceding month, each listed separately, showing:

- The change order number; and

- The increase or decrease in the contract price.

The net total of the current month’s issued change orders is shown in the totals column.

Construction contracts frequently include a contingency allowance against which the price of each change order is charged or credited. The Guide to the CCDC 24 Certificate for Payment Form contains an example showing a method for reporting these changes when this type of contract is used.

Adjustments to all allowances are made at the end of the work to determine a final contract price by issuing change orders that credit the unspent balance remaining in the allowance or add any overruns.

Other Certificates and Letters

The architect may be required to prepare other documentation attesting to the status of the construction contract and the actual performance of the work. Two common forms of certificates are listed below. Moreover, it is common for the architect to provide a variety of documentation to authorities having jurisdiction attesting to the general conformity of the building to applicable codes and other regulations.

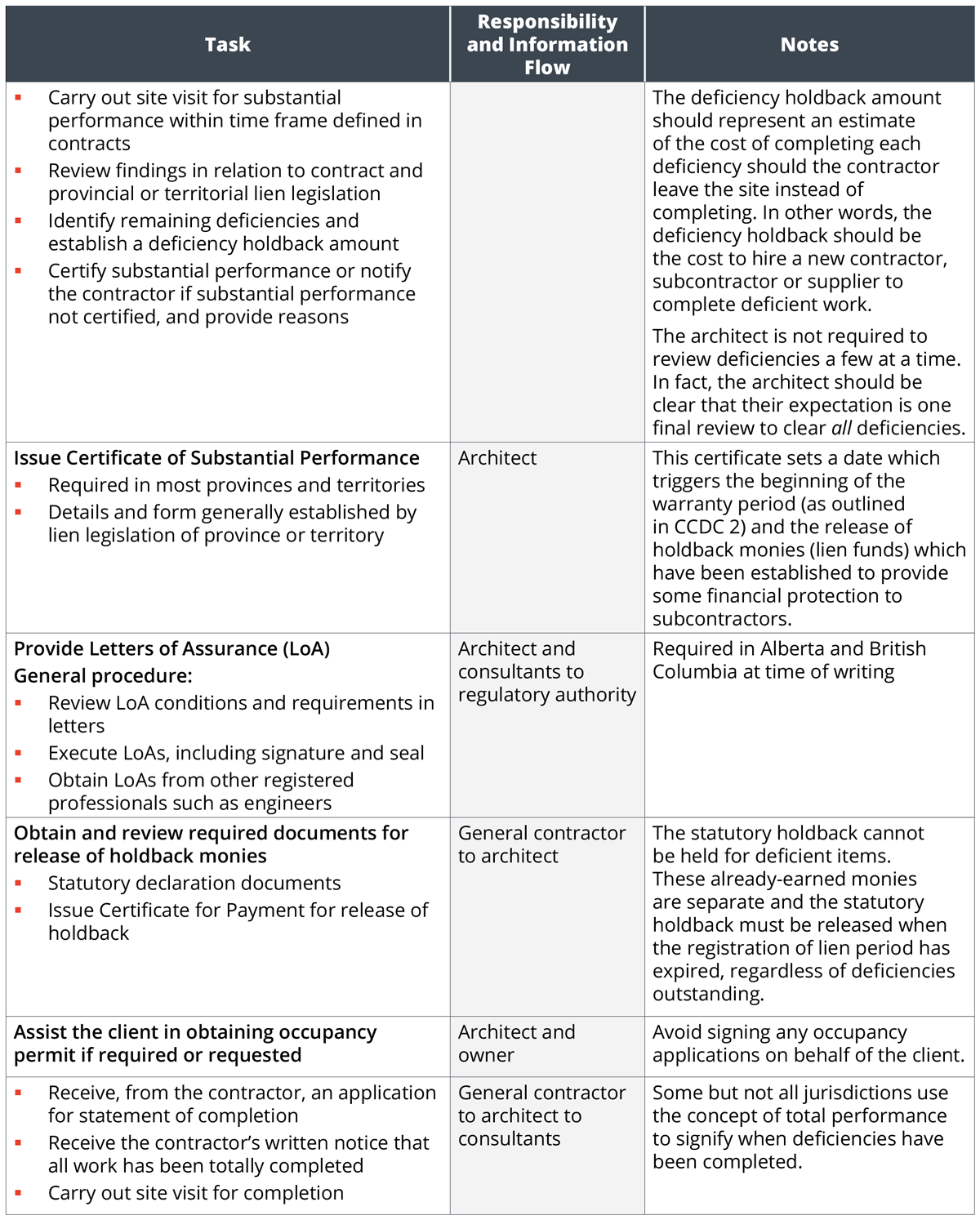

Certificate of Substantial Performance

In most provinces, the date of substantial performance of the construction contract must be documented. This certificate sets a date which triggers the beginning of the warranty period (as outlined in CCDC 2) and the release of holdback monies (lien funds) which have been established to provide some financial protection to subcontractors.

The architect must understand the lien legislation in the province or territory where the project is located and prepare a Certificate of Substantial Performance based on this legislation.

Refer to Appendix A of Chapter 6.7 – Take-over Procedures, Commissioning and Post-occupancy Evaluations for a list of the appropriate provincial or territorial lien acts to determine the amount of holdback and requirements for the release of holdback monies.

Letters of Assurance and Commitment to General Review

Several provinces require that licensed professionals who undertake review of building construction provide a Letter of Assurance or a Commitment to General Review. The purpose of these documents is to provide certification to authorities having jurisdiction that general review of construction is being undertaken by a licensed professional. All architects should refer to their provincial and territorial legislation and regulations and check with their associations for advice on the application of these certificates.

Letters of assurance must be signed, sealed, and dated by registered architects who are practising (principals) in architectural firms or who hold Certificates of Practice in designated engineering firms. The purpose of a letter of assurance is to provide certification to authorities having jurisdiction.

Close-out Services

As a project approaches completion, there are a variety of specialized contract administration procedures that need to be considered.

See Chapter 6.7 – Take-over Procedures, Commissioning and Post-occupancy Evaluations for tasks to be undertaken after the construction is substantially complete.

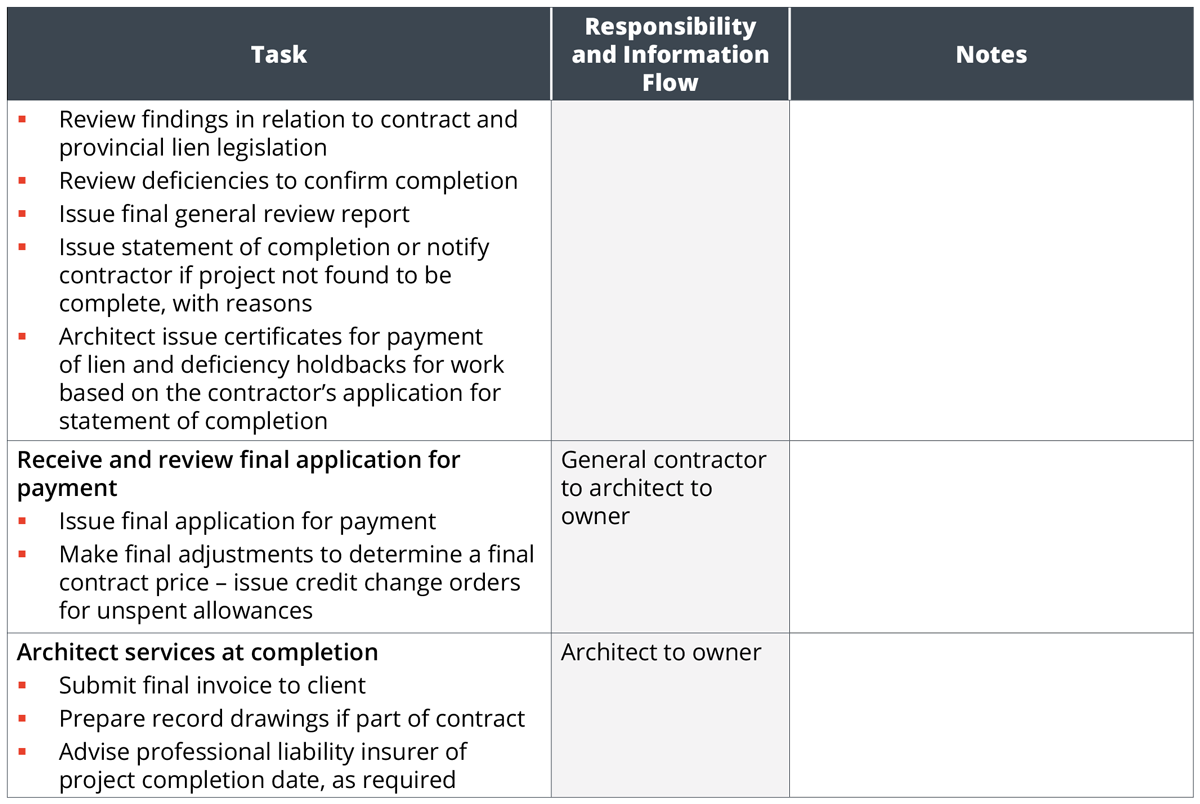

After Completion

Most construction agreements provide for a one-year warranty by the contractor in favour of the client. The standard RAIC Document Six client-architect agreement says that “the architect shall undertake a review of defects and deficiencies and notify the constructor in writing of items requiring attention by the constructor.” Meanwhile, CCDC 2 says, “The owner, through the consultant, shall promptly give the contractor notice in writing of observed defects and deficiencies which occur during the warranty period.”

The challenge of RAIC Document Six is that the architect may not have access for a defects and deficiencies review. The challenge of CCDC 2 is that its procedure is quite different from RAIC Document Six.

Each architect will have their own approach, but one that addresses these divergences is noted below.

Appendix

- Appendix A – Professional Standards for Field Review/General Review

- Appendix B – Continuous On-site Representation

- Appendix C – Fees for Professional Services for General Review

- Appendix D – Tips for Site Observations – General

- Appendix E – Checklist – Suggested Agenda for the Pre-construction Meeting

- Appendix F – Checklist – Typical Items for Shop Drawing Review

- Appendix G – Checklist – Items for General Review

- Appendix H – Checklist – National Building Code Final General Review

- Appendix I – Checklist – Architect’s Role in Soils and Materials Testing