Definitions

Business Case: A document developed to establish the merits and desirability of the project and justification for further project definition and the commitment of resources.

Feasibility Study: A report which outlines the research and subsequent analysis to determine the viability and practicability of a project. A feasibility study analyzes economic, financial, market, regulatory and technical issues.

Functional Program: A written statement which describes various criteria and data for a building project, including design objectives, site requirements and constraints, spatial requirements, relationships, building systems and equipment, and future expandability.

Gap Analysis: An analytical tool that identifies the difference between a current state and the desired state.

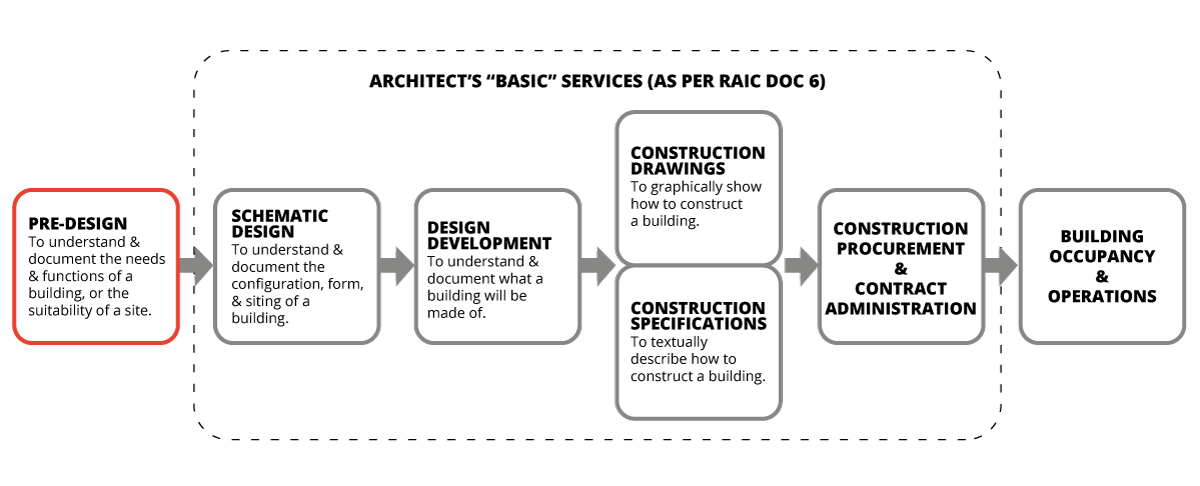

Pre-design Services: The architectural services provided prior to the schematic design phase which assist the client in establishing a functional program as well as the project scope, including a financial and scheduling plan.

Introduction

The purpose of the pre-design phase is to provide both the client and the design architect with a foundation and necessary information for design decision-making. During pre-design the purpose and objectives of the design-construction program are established. It is also during pre-design that clients make decisions on sites, what to do with existing capital assets and facilities, the structure of the program’s organizations, and the procurement methods to be used to acquire the needed resources for each project in the design-construction-operation program.

Some clients may have done significant capital planning, data collection and strategic analysis prior to pre-design. This work is an input to the pre-design process. Others may be less prepared and should be advised on the benefits of investing both time and financial resources in pre-design activities prior to proceeding with design.

The possible pre-design services that an architect may perform are far-reaching. This handbook describes some of the common examples, including:

- business cases and feasibility studies;

- project budgeting and cost planning;

- life cycle cost studies;

- functional programming;

- space relationships/flow diagrams;

- space planning and optimization;

- organizational and business planning;

- site evaluation and selection;

- master planning and urban design;

- building condition assessments;

- as-found drawings;

- project management framework;

- client-supplied data coordination;

- project scheduling;

- authorities having jurisdiction (consulting/review/approval);

- land-use analysis and re-zoning assistance;

- building code and fire safety analysis;

- presentations and project promotion (including public engagement and business collateral);

- design competitions brief or proposal calls documentation.

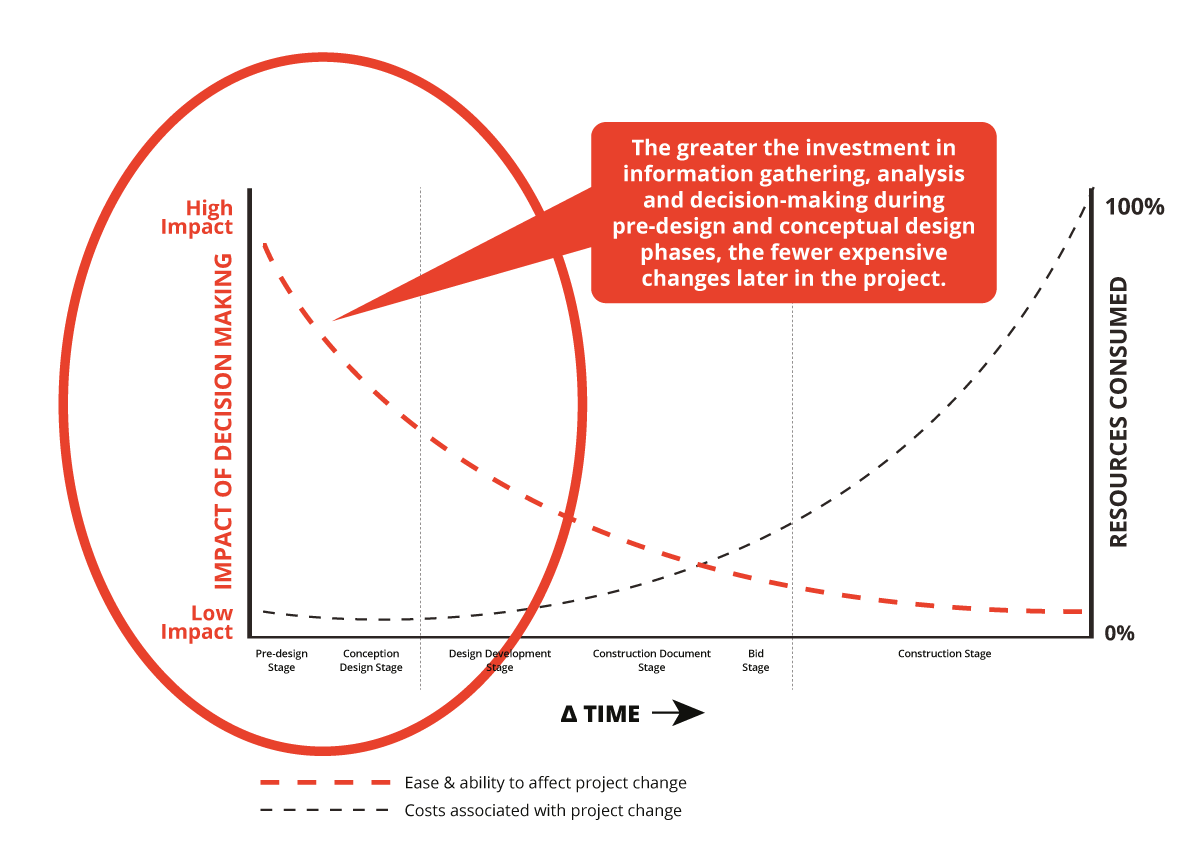

FIGURE 1 MacLeamy Curve: Influence of Early Effective Decision-making on Project Outcomes

"Strategic thinking that is informed by decision-making will have a positive impact on project quality, cost, and schedule. Clients that invest in integrated early design will realize increased value by significantly reducing the risk of project shortfalls. The MacLeamy Curve in Figure 1 illustrates that early design-based decision-making can lever resources to achieve successful project outcomes and operational efficiency. Reducing project costs by reducing the resources available for an effective design acts to work against the client’s best interests.”

– Royal Architectural Institute of Canada,

A Guide to Determining Appropriate Fees for the Services of an Architect, 2019

Pre-design is fundamental preparatory work for the later design phases of a project, and it often requires years to complete successfully. Though not part of the architect’s basic services, pre-design is integral to the overall delivery of the design project. A project that has invested in pre-design work is more likely to be delivered on time, on budget, and to the client’s expectations. Changes made during pre-design will have the greatest impact, with the least cost, compared to changes made at any later phase of the project.

An architect may also perform or coordinate other pre-design services, additional to those listed above. These services often require collaboration with experts in other fields. An architect contemplating these services is encouraged to do further research on the scope, fees, and other considerations for themselves. Checklist guides are provided (where noted) at the end of the chapter for further reference. These services may include:

- obtainment of legal survey from client (see checklist);

- environmental site assessments and hazardous materials reports (see checklist);

- coordination and review of geotechnical and soils reports (see checklist);

- existing facilities surveys for accessibility (see checklist);

- coordination and review of historic archeological landscape surveys (see checklist);

- site energy studies (see checklist);

- traffic impact and parking studies (see checklist);

- information technology studies and assessments;

- cost estimating;

- environmental planning;

- historical building research and assessment;

- archaeological research and assessment;

- marketing studies and special studies;

- real estate appraisals;

- financing and accounting;

- site plan agreements and development agreements;

- management consulting.

Some pre-design services may lead to actual building design commissions; others may not. Before taking on pre-design work, the architect should be aware if doing so contractually precludes them (and their subconsultants) from any future related design commissions. Public sector clients will sometimes deem an architect who performs pre-design work ineligible to be awarded design contracts due to the perception that they may hold an unfair advantage over other architects competing for the same commission. Conversely, with other clients, a pre-design project could set the architect up for a seamless transition into a design commission.

See also Chapter 3.9 – Architectural Services and Fees.

Pre-design Services and Team Organization

As generalists, architects can provide broad perspectives on their client’s requirements. However, pre-design services require specialization and currency in fields which are related to, but different from, traditional architectural practice. Certain pre-design services, including many of the above-noted examples, will require the skills of specialist subconsultants to deliver. In these projects, architects act as prime consultants, or leaders of multi-disciplinary teams, coordinating pre-design services.

The opportunities for prime-consulting architects, and assembling and coordinating subconsultants, include:

- levering their own capabilities as generalists and problem-solvers;

- sourcing the necessary subject matter experts;

- balancing the competing concerns of multiple subconsultants;

- staying current in specialized fields;

- managing and monitoring communications and setting expectations across the pre-design team;

- assisting with obtaining project funding;

- maintaining consistency and quality of the overall work.

Successful projects are consultative and iterative processes, requiring the architect to facilitate optimal outcomes for the client and stakeholders. At pre-design, by definition, the design has yet to materialize, and the eventual solutions are not yet clear. It is therefore important for the architect to set the team up with enough time and resources for pre-design, and the subsequent design phases, to facilitate good collaboration.

The definitions of some of the typical pre-design services are often subject to different interpretations by all stakeholders involved in a design-construction program. For example, the term “program” can imply different things to different members of the team, and to the client. A “program” in the context of design refers to the document that contains the functional requirements that the design must satisfy. In a project management context, it refers to a grouping of projects and operations that are coordinated and managed together for greater efficacy. The purpose of this chapter is not to prescribe exactly what pre-design services must consist of, but rather to acknowledge the variations in understanding that an architect will likely encounter, and to prepare them for their role in establishing effective communications and team consensus when developing pre-design scopes, performing services, and preparing deliverables.

Each architectural practice must decide whether it wishes to employ pre-design expertise in-house or offer these services via subconsultants. Alternatively, an architect may develop a practice which specializes in pre-design services. Regardless, successful pre-design work depends on both an appropriate team of experts, and a collective awareness of how important pre-design is to the later phases of design, construction, and operations. These competencies come from exposure to, and experience in, a broad set of disciplines.

Chapter 2.3 – Consultants contains a more comprehensive list of specialist subconsultants.

Setting Up Project Workflows and Systems

Business Cases and Feasibility Studies

A business case is a document that justifies the financial investment and resources to turn an idea into reality. Information in a business case includes the background of the project, the expected business benefits, the options considered (with reasons for rejecting or carrying forward each option), the expected costs of the project, a gap analysis or the variance between business requirements, current capabilities, and the expected risks. Consideration should also be given to the option of doing nothing, including the costs and risks of inactivity. It should describe the idea, problem, or opportunity, who will be impacted by the outcome of the endeavour and what that impact will be. Business cases provide analysis on:

- the background of the project;

- the expected benefits, including financial benefits;

- alternative options (with reasons for rejecting or carrying forward each option);

- the expected costs of the project;

- a gap analysis demonstrating the difference between the current state and the expected state upon completion of the endeavour;

- possible risks, including both threats and opportunities;

- analysis of the “doing nothing” option to account for the costs and risks of inactivity;

- recommendations and plan for proposed next steps.

The complexity of a business case, and the time needed to prepare it, depend on the client’s needs. Many public sector and corporate clients have multi-stage approval processes. The outcome of a business case may spawn additional analytical work, such as a feasibility study, financial, risk and market analysis, and operational change analysis, which may in turn generate more studies for funding, resources and approvals.

Feasibility studies take many forms, but they generally expand on the financial focus of a business case by considering the broader macro-economic, regulatory, political, social, operational, and technical practicalities of an initiative, often incorporating:

- functional programs, including general space requirements and functional relationships;

- regulatory studies to determine code, zoning constraints, urban design objectives, heritage considerations and community input related to a project;

- site identification, analysis and evaluation;

- environmental impact analysis;

- social impact analysis;

- traffic impact analysis;

- financial studies identifying:

- strategic or business plans;

- capital, operating and life cycle cost estimates;

- potential partners;

- market studies forecasting demand and real estate market value of a completed project;

- buy/sell/lease scenarios analysis;

- capital costs;

- life cycle costs for operating, and maintenance costs;

- sources of revenue, including funds to offset capital and operating costs;

- co-location and mixed-use potential;

- demographic studies predicting demand and, possibly, preferences and lifestyle trends;

- organizational and operational change analysis;

- public/stakeholder engagement sessions;

- valuation of land and sites;

- evaluations of existing facilities, including:

- mechanical, electrical, structural and envelope systems;

- functional adaptability;

- code compliance;

- programmatic analysis to determine feasibility of accommodating program requirements in facility(ies);

- exploration and analysis of alternative sites and solutions;

- schedules for:

- project development;

- cash flow planning;

- project phasing, swing space and decanting.

Designing is often a very open and consultative process, involving the architect, the client and various stakeholders. Architects provide pre-design services and undertake feasibility studies to deal with an increasingly complex regulatory environment. Therefore, feasibility studies may examine:

- official plans and community plans;

- zoning and land-use controls;

- designated activity districts within cities;

- transportation issues;

- heritage districts;

- community organizations and concerns;

- civic design panels;

- building codes;

- environmental issues.

For government clients, feasibility studies could include an exploration of economic partnerships with the private sector because, depending on economic or political conditions, governments may choose to reduce capital spending on public projects. These initial explorations could lead to an alternate funding plan (AFP) or public-private partnership (P3) project delivery method. These clients may also take social and environmental factors into account, along with economics, to calculate the return of a project on a triple bottom line basis: social, environmental, and financial impacts, or people, planet, and profit.

Many clients are also increasingly interested in renewing buildings and infrastructures rather than replacing them. In such cases, a feasibility study might assess the potential for reusing existing building systems and identify any existing heritage value.

The regulatory environment that all clients operate within has become increasingly complex and onerous. This has driven the need for their architects to prepare increasing amounts of feasibility analysis before approvals will be granted by authorities. It is important for the architect not to underestimate the amount of time and resources spent on business cases and feasibility studies before a project can proceed to design and construction. These are additional services that often require the knowledge and expertise of senior members of the design team. The architect is advised to ensure that appropriate fees are charged for these services.

Budgeting, Cost Estimating and Financial Planning

Clients normally come to the pre-design process with a budget indicating the financial resources that they are prepared to commit to a project. A budget is not a cost estimate, but a determination of the worth of the project to the client. In simple terms, a cost estimate must be compared against the budget. If the cost estimate is lower than the budget, the project may be worth undertaking. If the cost estimate is higher than the budget, the project may not be worth doing.

More detailed financial breakdowns, such as land costs, hard costs, soft costs, carrying costs and contingency, are usually first addressed at the pre-design phase. Data and information about the proposed building at this stage are broad in nature; therefore, cost planning will likewise be at a tentative degree of accuracy, which may have a wide variance of -50% to +100% of actual cost.

There are several common conventions for classifying the accuracy and progression of cost estimates. A pre-design cost estimate may be called an order of magnitude or class D estimate. To promote clarity within the project organization, including the design team, the client and key stakeholders, the architect should establish the conventions to be used on the project to communicate cost information.

The pre-design architect must be familiar with the cost information available for early cost-estimating, for example:

- hospitals use unit-of-service measures, such as $/bed, and the number of beds per catchment area;

- some educational institutions use the number of students to determine the gross space requirements;

- clients may have their own models for determining the likely capital costs of construction.

If a client does not have a budget, or is not prepared to disclose their budget, the architect is advised to ensure that cost information, including projections of the cost estimate’s accuracy, assumptions, limitations, constraints and associated project risks, are communicated to the client in clear and understandable terms. It is also important for the architect to clearly articulate the differences between construction costs and project costs to a client during the cost estimation process. Financial plans break out these costs and are typically presented as a “pro forma,” not usually prepared by the architect, including:

- hard development costs (construction and land costs);

- soft development costs (such as professional fees, realtor fees);

- financing and carrying costs;

- market revenue analysis;

- escalation;

- rates of return on investment and capitalization.

Of these parameters, the architect can usually only comment on construction costs and professional fees. Other experts will be required to provide the client with the complete program cost estimate.

The completed financial plan should identify “how much building must be built” (scope of the project) and should establish a preliminary financial analysis indicating capital costs on a unit area basis. One purpose of a financial plan is to provide information to prepare a project budget and construction budget to base the design phases on. To this end, it’s important for the architect to obtain client sign-off on the budgets at the end of pre-design.

See also Chapter 4.2 – Construction Project Cost Planning and Control.

Life Cycle Cost Analysis

Over a typical building’s life cycle, its operating and maintenance costs will exceed its initial capital investment many times over. Tradition has accepted an office building’s design-construction/maintenance/building operating costs ratio to be 1:5:200. However, research has not validated this widely held belief. Research by Hughes et al. has found that for office buildings, a ratio of 1:0.4:12 is more valid. Depending on the building type, this ratio may vary. In complex buildings such as hospitals, when long-term staffing and energy costs are considered, the capital cost of the facility may be as small as 2% of the total cost of the facility over a 35-year operating cycle. With the cost of design and construction of a facility being a small part of an organization’s total costs, effective design decision-making can have a significant influence on future total operating costs.

Architects can assist building owners and operators to understand the long-term financial commitment implied by their up-front capital investment in a building. Life cycle cost analyses are often used to demonstrate the return on investments of various energy-conserving strategies which may be under consideration for the project. The viability of leasing instead of building may also be shown by this kind of study.

Functional Programming

Functional programs may also be called design briefs, facilities programs, building programs, architectural programs, statements of requirements, space needs or, simply, programs. Regardless of the title, the purpose of a program is to identify the problem to be solved by asking fundamental questions, such as:

- What are the client’s needs and objectives?

- What is the scope of the project?

- How much and what type of space is needed?

- What kind of site is needed?

- How will the spaces and systems relate to one another?

- How will the facility adapt over time?

- What other information is required to develop a proper architectural response? What are other constraints?

Time and money can be wasted because of lack of appropriate direction from a client. A functional program, which is developed jointly by the architect and the client, clearly defines the problem. Good functional programs result in better and more effective design solutions.

In preparing a functional program, the architect examines the client’s world in detail to uncover the cost, time, performance and formal criteria for evaluating later design solutions. When an architect reviews a program provided by a client, the architect must comprehensively, tactfully and proactively comment on the program to identify challenges, conflicts and risks.

A functional program describes the requirements which a building must satisfy in order to support and enhance human activities. The programming process seeks to answer the following questions:

- What is the nature and scope of the project parameters, needs and opportunities?

- What information is required to develop a proper architectural response?

- How much and what type of space is needed?

- What space will be needed in the next five to 10 years or longer to continue to operate efficiently?

In preparing a functional program, the architect’s main task is to examine the client’s world in detail to define the client’s needs and objectives. These requirements will establish criteria for evaluating potential design solutions or other strategic alternatives. The architect must understand:

- the impacts of a building’s occupants and processes on the built environment;

- the social impacts of its program on the community;

- the planning impacts of its functions on the local infrastructure.

Sometimes, for simple or small projects, the functional program is prepared as part of the schematic design phase. Otherwise, programming is a distinct additional service requiring dedicated time and resources. A program may be a simple summarizing spreadsheet, or an exhaustive document which captures extensive information and data. As such, the architect should understand the client’s requirements and negotiate an appropriate scope, additional to any “basic” services being provided to the client. The time and money invested in programming will provide the design team and stakeholders with a clear idea of a building’s purpose, resulting in more effective design solutions.

There are several approaches to developing a functional program, but collaborative methods involving the client and the stakeholders have greater chances of achieving shared visions. This is ultimately essential to producing a program that educates the design team to produce a building design that is fit for the purpose. During this iterative process, architects typically observe, document and analyze the uses intended within the prospective building, including:

- the users of the proposed building and their work activities, including:

- function-by-function, and space-by-space or department-by-department activity plans;

- organizational plans and occupant loads;

- staffing level plans, including hours of operation and shift work;

- storage and support space;

- gross-up factor applied to functional areas, which includes circulation, mechanical and electrical system space, structure, etc.;

- volumes of activities planned for specific facility components, such as:

- throughput (material put through a manufacturing process);

- flow patterns, operational process flow diagrams, and human activities;

- precedents and similar building types.

Additionally, the architect must also consider how the program relates to other external factors, such as:

- the site and the community;

- environmental, social and economic impacts;

- the capacity of local infrastructure;

- regulatory constraints;

- sustainability/regenerative goals.

With this information, the architect can then develop approximate floor areas, and document any special technical considerations, including:

- critical dimensions of the space and workstations;

- durability and maintenance requirements of finishes, furnishings and equipment;

- environmental criteria, including air quality;

- hardware requirements such as for IT, A/V, cabling or security requirements.

The architect’s services may also include guidance on alternatives, such as various massing and siting options, high/medium/low growth projections, the possibility of phasing, the effects of budget, and differing operational process models. These services assist the client in understanding and assessing the relative costs and benefits of alternative approaches to the project.

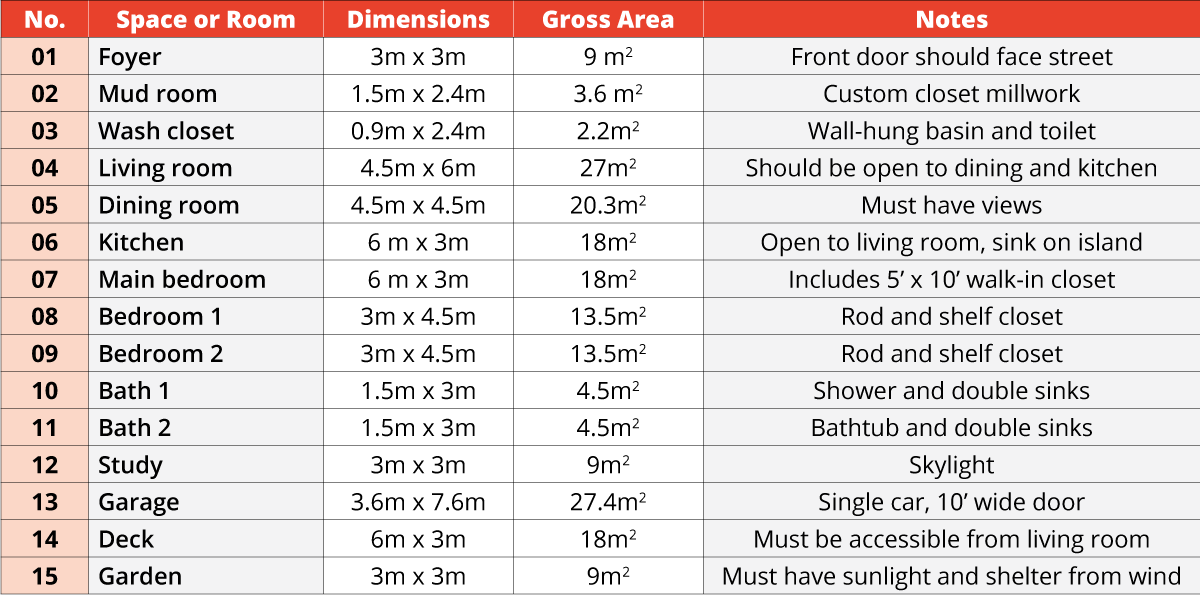

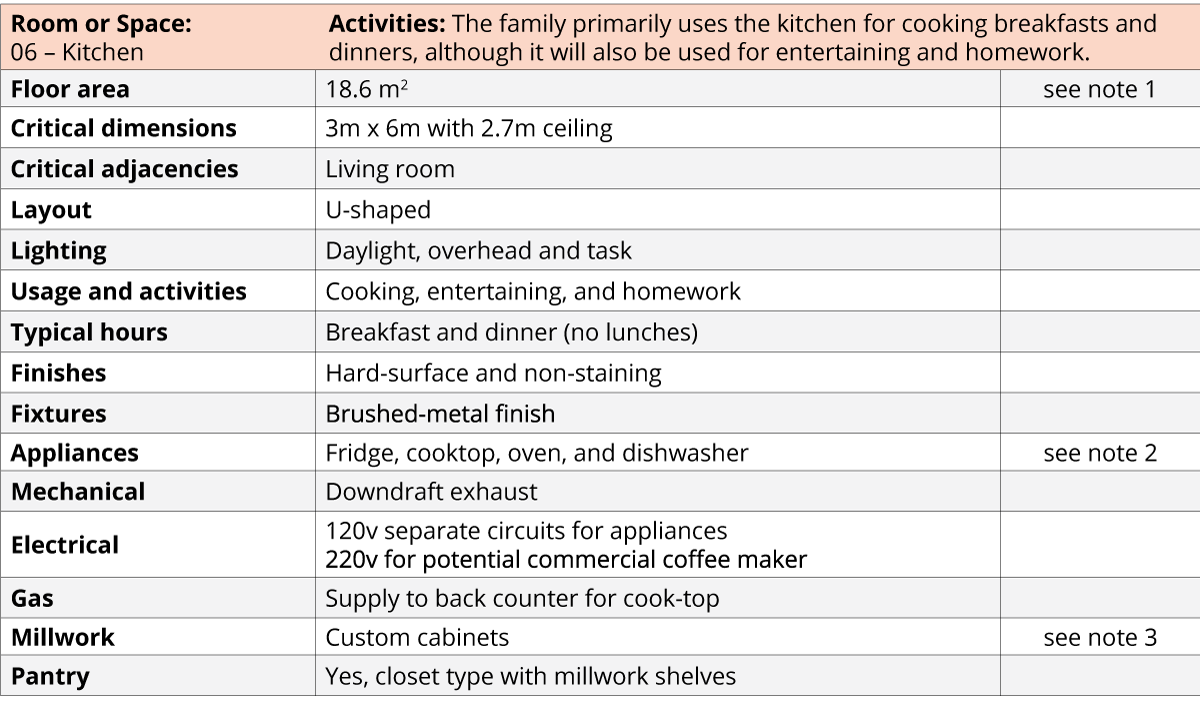

The process of functional programming results in a report which typically includes items such as:

- the client’s goals and values;

- a stakeholder “charter” describing the shared vision and design principles for the project;

- itemized site requirements, such as parking, circulation, orientation, transportation and accessibility;

- a summary table of space types and areas (see Table 1 below);

- detailed space data sheets (see Table 2 below), which include information such as:

- activities and sizes;

- adjacencies and separations;

- special technical requirements of each space, including systems and equipment;

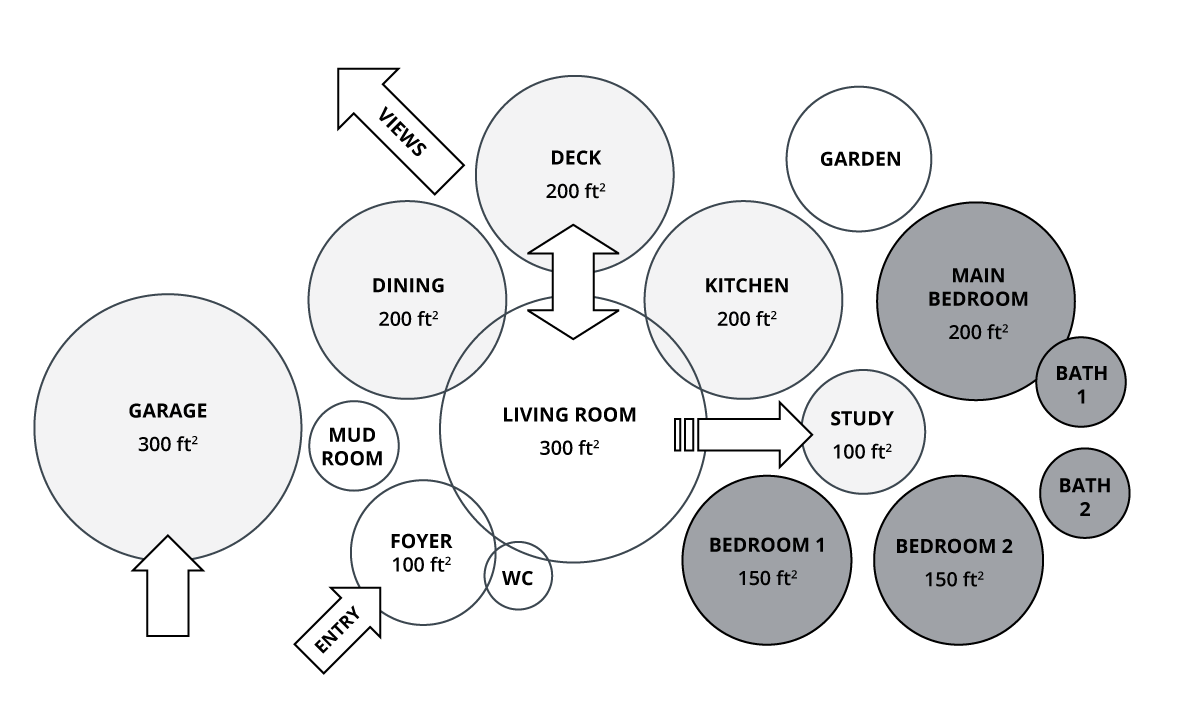

- a space-relationship (or “bubble”) diagram (see Figure 2) which graphically depicts:

- the relative sizes of spaces and their relationships to one another;

- the primary entry, egress and circulation patterns;

- any site considerations which the design should respond to, such as solar orientation, views, prevailing winds and noise;

- financial requirements, projected cash-flows, anticipated life cycle costs and a preliminary budget;

- project phasing, scheduling and milestones;

- a regulatory approvals strategy, including land use, building code and other applicable restrictions;

- a proposed procurement and project delivery method;

- community goals and concerns;

- ecological and environmental concerns;

- a recommended construction project delivery method.

An architect’s involvement in programming does not necessarily guarantee their continued services on the design phase(s) of the project. Often one architect’s functional program is provided to another architect commissioned to design the building. This reality should be considered throughout the performance of programming services.

Tables 1 and 2, and Figure 2 below illustrate fundamental space and configuration information that form part of a functional program for a single family residence.

TABLE 1 Summary of Space Types for a Custom Residence

TABLE 2 Sample Detailed Space Data Sheet

NOTES

- Actual net area may vary by +/- 4.6m2, subject to schematic design.

- Appliance budget has been established by client.

- Cabinet supplier to be identified by client.

FIGURE 2 Sample Space Relationship and Flow (Bubble) Diagram for a Residence

Programming Skills

Programming requires specific skills. The programmer must develop the ability to understand a client’s philosophy, values and management style in areas such as:

- organizational behaviour;

- decision-making;

- success measurement;

- future objectives;

- environmental and social responsibility.

To develop this ability, the pre-design team relies on knowledge and methodologies from other fields such as:

- the social sciences;

- management sciences;

- operations research;

- industrial engineering.

In addition to architectural ability, the architect may require expertise in such fields as management consulting and real-estate development to undertake functional programs. Along with research expertise, the architect needs advanced interpersonal and facilitating skills.

The architect often uses the following techniques:

- research and study of best practices;

- observation (of the client’s existing site or workplace);

- interviews and direct consultation with end users of the facility;

- public consultation;

- facilitation of focus groups;

- questionnaires and surveys.

Sometimes stakeholders have conflicting viewpoints which the architect can help resolve by collaboratively identifying the underlying issues, then developing optimal solutions by incorporating common interests and by incenting compromise. Typical sources of conflict include:

- competing interests or needs that may exist within the client organization (for example, end users such as tenants, teachers or medical staff may have very different priorities and needs compared to those of landlords, school boards or regional health authorities);

- the involvement of different members within the organization, or more than one organization;

- multiple funding sources with different conditions attached to expenditures.

Due to the impartial arm’s-length relationship architects have with stakeholders, they often play a unique and important role in helping resolve conflicts by mediating and facilitating optimal compromises that the client would otherwise be challenged to resolve on their own.

Data Management

Functional programming requires gathering, analyzing, organizing, reformatting and retrieving data to produce information. The architect or the programmer must know how to apply analytical, problem-solving and decision-making tools, and use data management systems to systematically store and retrieve an enormous amount of detailed information. The architect must present this data to the client clearly to enable the client to make effective decisions. At the simplest level, a series of spreadsheets may be used to gather and sort information. If functional programming is a service routinely delivered to clients, a relational database system would generate significant core competency and competitive advantage.

Space Planning and Optimization

A primary purpose of most functional programs is to determine the optimum size of a building by understanding the sum of all the constituent spaces, and the efficiencies that may be gained by configuring them in particular ways. Architects can add great value for clients during pre-design by critically examining the stakeholder’s claimed requirements to identify excessive allowances, redundancies which could be eliminated, and opportunities for shared space. This can ultimately reduce the overall area of a building, which will in turn help control the costs of construction and operations.

The optimal amount of space required is partially ascertained from first principles of architectural design, such as:

- the number of people or pieces of equipment that will occupy the spaces;

- the nature of the activity in the space;

- associated equipment, inventory and storage facilities;

- harmonization of space requirements and structural systems;

- process modelling and layout experiments.

Architects also need to consider current space standards and references which relate to the activities and processes outlined in the program. The most reputable standards are developed from large amounts of data and provide ranges that allow for special exceptions. See Chapter 2.5 – Standards Organizations, Certification and Testing Agencies and Trade Associations for a discussion of standards.

In pre-design work, an understanding of net and gross floor areas is essential for determining the probable size of a building. Architects working for the commercial sector need to be familiar with the floor area measurements used for leasing purposes. The Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA) publishes the Standard Method for Measuring Floor Areas in Office Buildings, a standard known as ANSI/BOMA Z65.1-2017. Other agencies at the federal and provincial level publish floor area standards for other building types.

Business Organization Planning

Some clients may use the decision to optimize space and/or build new facilities as a catalyst for organizational or administrative change. The architect may become involved in this process, necessitating the following kinds of work:

- process mapping;

- re-alignment of services, or business divisions;

- organizational and reporting re-structuring;

- staff counts, job descriptions and competency profiles.

Conversely, organizational planning can also cause a client to review their portfolio of facilities, which then often results in new buildings, improvements to existing buildings, and sale of old buildings.

Change management helps facilitate the acceptance of organizational change amongst staff, facility operators and customers. The architect may participate in the development of a change management plan, which provides a rationale for re-organization, time frames, and plans for communications and re-stacking.

Information on organizations and management is available through degree programs, management training courses, and self-directed research.

Site Evaluation and Selection

Site evaluation is a pre-design service. It includes evaluation of existing or potential sites in relation to the building program, budget and construction schedule. Normally, one site is then recommended.

Site analysis of a single site in the pre-design phase is usually a separate service. In certain circumstances, site analysis may be undertaken as part of the schematic design phase of a project and the fee should be adjusted accordingly.

Some clients speculatively own land well in advance of developing buildings on it, while others may not yet even have considered their need for a site, let alone acquired one yet. As such, site evaluation and selection are tailored pre-design services that can provide immense value for clients who have land investment horizons of years, or even decades. Site analysis typically includes evaluation of existing or potential sites in relation to budget, phasing and scheduling. Test fits help indicate how a site may accommodate a program. Normally, one site with net advantages over the others is then recommended.

Site analysis is not a basic architectural service but is an additional service. (Refer to the RAIC’s A Guide to Determining Appropriate Fees for the Services of an Architect.) Site analysis may be undertaken as part of the schematic design phase of a project, so the scope and fees should be adjusted accordingly. To perform robust site analysis, the architect should collect and consider many kinds of information about the site, including how it compares to other similar sites, its physical characteristics, applicable regulations which will restrict development, and its highest and best use.

Comparative Site Studies

The concurrent analysis of several sites, using consistent measures such as constraints, adaptability, and development impacts, is used to rank the suitability of the sites and advise the client accordingly. Categories of analysis will be specific to the client’s needs, but may include size, cost, land-use, location, access, utilities, capacity for growth, etc.

Physical Site Characteristics

To analyze the site for desirability and feasibility of development, the architect requires the following information:

- existing conditions which have an impact on the design:

- climate, including prevailing winds, solar orientation, etc.;

- topography, including site contours, drainage, water courses, visual characteristics, physical features, vegetation, water bodies, rock outcrops, etc.;

- geotechnical or soil information;

- environmental hazards;

- immediate surroundings, including neighbouring structures, shading and solar access, noise, views, and vistas;

- site servicing;

- road access;

- property description:

- legal description, including boundary survey, easements, rights-of-way, etc.

Legal Restrictions, Land Use and Other Regulations

It is an additional requirement to identify all the regulations which apply to the site, including:

- legal title, including a survey, easements, caveats, rights-of-way, restrictive covenants, and other encumbrances;

- land use, including:

- permitted uses;

- height and size restrictions;

- setbacks and lot coverage;

- open space requirements;

- parking requirements;

- accessibility requirements;

- architectural controls and design guidelines;

- environmental remediation requirements;

- historical resources;

- floodway and seismic restrictions;

- other regulations which may also exist.

An architect may provide added value to the client’s project by leading or assisting with the applications to amend or remove legal restrictions in the development or use of a site. These kinds of permissions are normally granted to applications seeking minor variances from the existing restrictions, or significantly greater variances in cases where a developer concedes to provide a social or community amenity considered of public benefit, such as park land.

It may also be necessary to prepare presentation material to assist in the formal procedures for development approvals. The architect may be expected to make presentations to municipal committees or at public meetings during the pre-design stage of a project.

See also Chapter 2.4 – Building Regulations and Authorities Having Jurisdiction.

Highest and Best Use

Land value is usually appraised according to what’s known as its “highest and best use,” or the way the land should be (re)developed for maximum productivity, given any technical or legal restrictions, and the current market conditions. Landowners may have the discretion or desire to develop a building that does not provide maximum productivity for a site. Sometimes there may be incentives for a site to be underdeveloped. Other times the authorities having jurisdiction may require a minimum intensity of uses on a site. Although the highest and best use will always vary site by site, the architect can add value to the client’s project by being aware of how to, and proposing uses that, maximize the value of the site for them.

See the site evaluation checklists at the end of this chapter for complete lists of factors to consider when evaluating a site.

Master Planning and Urban Design

The terms “master planning” and “urban design” are often incorrectly used synonymously. While there are certainly overlaps in the two services, there are important distinctions.

Master plans define long-term development strategies and layouts for specific sites, campuses or communities, including building locations, infrastructure and circulation. A master plan can sometimes follow completion of a functional program to establish phased projects over time across a site. Master plans may sometimes be required by planning authorities for a land-use approval, thereby making the master plan a statutory document that must be adhered to. Often master plans will also include a feasibility analysis of the economic, phasing and constructability issues.

By comparison, urban design is a specialized discipline with a broader scope than master planning. It includes all scales, from the layouts of entire cities to the streetscapes and public realms between buildings, and details like street furnishings and paving patterns of the sidewalks. Urban design focuses less on land-use regulation and feasibility, and more on design concepts such as place-making and networks. Consequently, it gives more attention to critical dimensions, proportions and textures of open urban spaces than a master plan typically would.

Although master planning and urban design imply building forms, they are both usually considered distinct from architectural design. The architect is in a unique position to provide strong leadership on master planning and urban design teams, but it’s important not to think of these disciplines simply as extensions of building design. The scope of work of each master planning or urban design project must be assessed, as each project is unique. A significant variation between clients and projects is the level of built form resolution required. The scope of work may be determined by the requirements of authorities having jurisdiction and governmental approval processes.

Just as a building requires a program, public outdoor spaces also need programs that articulate the multitude of functions and characteristics needed of public and private urban spaces. Master plans and urban designs may take years or even decades to build out, so consideration should be given to longevity and future-proofing strategies.

Building or Facility Condition Assessments

Facility managers need to know the overall physical state of their existing buildings to properly understand any current deficiencies, deferred maintenance, remaining life cycle, and projected capital requirements. This helps the owner, who may hold an entire portfolio building, develop investment strategies and budgets for their assets. Building condition assessments (BCA) or facility condition assessments (FCA), usually performed every three to five years, inform building owners’ decisions to invest in, or divest of, their buildings. Many portfolio managers, including government entities, have specific formats and requirements for their building or facility condition assessments.

BCAs and FCAs normally require the architect to perform an on-site visual review, using non-invasive means, of all major systems of the building and its site. This review should be documented with photos, notes, sketches and readings from remote sensing devices like infrared thermometers and moisture meters. The architect may also incorporate client-supplied records and data. In some cases, invasive testing by expert subconsultants might be required.

The analysis normally consists of itemizing all building systems and major components, with estimates of the remaining life of, and cost to replace, each item. The analysis may also include prioritization, opportunities for bundling work, investment scenarios and budgeting strategies. The architect may then calculate a facility condition index (FCI) number, which is the ratio of total maintenance, repair and replacement costs required for a building, to its current replacement value. The lower the resulting number, the better the condition of the building. The FCI allows the facility manager to understand the relative condition of a building, and to track the effects of investments or deferred maintenance over time.

It is important to note that BCAs and FCIs only provide a general indication of a building’s state. These assessments normally require deeper interpretation to become implementable plans for maintaining and upgrading a building. Indeed, in some cases, such as when the subject building is technically specialized or has heritage status, the assessments should be validated against current market rates to give a true cost, prior to budgeting the work.

As-Found Drawings

The terms “as-found drawings,” “as-built drawings,” “measured drawings” and “record drawings” are often incorrectly understood and interchanged.

As-found drawings fall properly within the scope of pre-design services, whereas as-built and record drawings are normally prepared during/after construction to document the general conformity of a building to the architect’s design. Measured drawings may refer to as-found drawings, or drawings prepared by a surveyor for leasing and sales purposes. Therefore, it is critical to clarify with the client what the purpose of the drawings is, and the accuracy required, so that the drawings can be prepared appropriately.

As-found drawings are based on field measurements taken from an existing building which is usually being considered for an addition, renovation or rehabilitation. They normally document the dimensions and layout of an existing building’s finish surfaces, both interior and exterior. They should be understood merely as inputs to the design process, and should not be used for tendering or construction purposes. As-found drawings should also generally abstain from speculating on the unconfirmed construction assemblies of floors, walls and roofs. It may be appropriate, however, for the drawings to include notes on the general observed condition of finishes, and to indicate where building elements require further investigation or invasive testing by the appropriate expert(s). Photographs are also useful supplements to the drawings.

Verifying the Accuracy of Client-Supplied Drawings

If provided drawings by the client, the architect should take reasonable steps, including reviewing the drawings, visiting the site, and confirming key dimensions, before relying on them. Measures should be taken to ensure the drawings remain identifiably distinct from drawings produced by the architect.

Client-Supplied Data Coordination

One of the normal contractual responsibilities of the client is to supply programmatic, budgetary and scheduling data. The client normally also supplies a site survey. Once obtained from the client, the project architect has the responsibility to collect, review and circulate this data amongst the subconsultant team as necessary. Basic project management protocols and tools for the centralization and dissemination of data may help ensure it is accurately and efficiently channeled. This work is performed as part of “basic” services throughout design phases, but it is considered an optional extra service during pre-design.

Project Management

Project management is a specialized field with its own designations, processes and terminology. It is advisable for an architect to seek out project management training and resources prior to providing services as a project management service provider. (See Chapter 3.10 – Other Architectural Services, Appendix C – Architect as Project Management Service Provider.) At the very least, it is useful for an architect to have an understanding of project management to facilitate conversations and processes with project managers.

The roles and responsibilities of project architects and project managers are often misunderstood and intertwined. Normally, they are two discrete positions on a project team, but on smaller projects both positions may be played by the same person. Often larger corporate or governmental clients will appoint their own project manager for the project architect to liaise with. Larger contracting companies will also usually assign a project manager to a project. Regardless, it is important to recognize that someone needs to be responsible for the specific architectural deliverables of a project, and someone needs to be responsible for the overall project execution.

It is also important to note that project management of the design project is the responsibility of the project architect and is considered a part of the architect’s services during the design and construction projects.

See Chapter 5.1 – Management of the Design Project for a detailed discussion of the difference between the roles of project architect and the project manager.

Project Scheduling

Not to be confused with the scheduling of work activities of the architectural design project, pre-design project scheduling is an exercise in forecasting the anticipated phases and milestones of the design and construction program to the nearest week, month or even quarter. This schedule may also include general activities, resources, cash-flow projections, critical paths, and fast-tracking opportunities. The intent and purpose of a pre-design schedule is to provide a broad proposed estimate of a project’s delivery and completion date. It differs in complexity from the kind of detailed work breakdown schedule that a contractor or project manager may develop to identify elemental tasks, activities, and deadlines. Schedules may be developed to allow for a range of alternative outcomes, including best-case, worst-case, and likely scenarios.

Authorities Having Jurisdiction

An authority having jurisdiction (AHJ) is a body which reviews and approves prospective developments for compliance with applicable regulations. At minimum, the AHJ will be the municipality upholding local land-use requirements and building codes. Other projects may be subject to provincial and federal AHJs which administer environmental, archeological, historical, transportation and other regulations. The architect needs to research the full range of AHJs that a project requires approvals from, and needs to consult with them as early as pre-design to understand how they may affect the project schedule, cost, complexity, design, construction and operations.

See also Chapter 2.4 – Building Regulations and Authorities Having Jurisdiction.

Land-Use Analysis and Re-zoning Assistance

“Land use” is the development of raw land into built environments, both urban and rural. “Land-use planning” is the regulation of development to achieve particular social, economic, or environmental results.

In Canada, except for some areas governed by Indigenous peoples, the provinces govern land use via plans and legislation that authorize municipalities to create and enforce zoning bylaws, which in return uphold the provincial land-use plans. Ultimately, with the exceptions as noted above, any given piece of land will have land-use and zoning restrictions that will greatly influence the program that may be accommodated on that site, and also the form of the building that the architect may design. It is therefore imperative that, whether a client already has a site or whether they are still selecting a site, land-use analysis is one of the primary investigations that a pre-design architect needs to conduct.

Local land-use bylaws are available from the authority having jurisdiction, and they dictate such basic development parameters as permitted uses, allowable heights, building setbacks and lot coverage. They may also force more particular restrictions, such as hours of operation and building character. Land-use bylaws can be challenging to comprehend and can even be contradictory. There may also be multiple related municipal plans, policies, standards, and guidelines that a building must conform to. Thorough familiarization with all the land-use restrictions is prudent before any design begins, or before a site is selected. It is often advisable to seek early interpretation from the authority having jurisdiction on any regulations that may be unclear or inconclusive.

In some cases, a landowner and a municipality may share a mutual desire to see a site developed differently than the land-use bylaws permit. Under these circumstances, the architect may assist in either obtaining relaxations to the existing zoning to accommodate minor variations from the regulations, or outright rezoning of the site to permit a significantly different development than would otherwise be allowed. Relaxations are often granted at the discretion of the administrative planning staff, but rezoning is subject to an extensive public process and requires authorization from the local council.

The architect can help add significantly to the development potential, and value, of a site by rezoning it, but the time and effort should not be underestimated. The scope of services for rezoning services should therefore reflect both the potential rewards and risks of the work.

See also Chapter 2.4 – Building Regulations and Authorities Having Jurisdiction.

Building Code and Fire Safety Analysis

A pre-design building code and fire analysis is less detailed than the code reviews conducted throughout design. It gives an overview of considerations such as the major occupancies of the proposed building, any prohibited occupancy combinations, occupant loads, exiting requirements, any fire separations and the general construction type(s) of the proposed building. Having these understandings early can inform the program, cost estimate and schematic design. This in turn helps reduce the risk of later rework and redesign.

See also Chapter 2.4 – Building Regulations and Authorities Having Jurisdiction.

Presentations and Project Promotion

One of the primary undertakings during pre-design is generating support, participation, approvals and money for the project. This often involves demonstrating compelling architectural concepts to authorities, financiers, purchasers, the public, and other non-experts in the fields of design and construction. Presentations are a key tool with which the confidence of these important groups can be gained. Indeed, some of these groups may even require presentations as part of their due-diligence and approvals processes.

The architect may be asked to prepare and conduct presentations on their own, or as part of a larger team of presenters. Regardless, persuasive presentations rely largely on graphics and imagery that paint exciting impressions of the project. Because of an architect’s graphic skills, they are often the key supplier of visuals, including site photography, artist’s renderings, digital animations, charts and graphs for presentations. Those architects wanting to become more confident presenters should seek out resources on public speaking.

Every presentation should be tailored to the audience, but in general, a pre-design presentation should achieve a level of resolution that is evocative of architecture without prescribing the architecture. This balance is important because the intention of a pre-design presentation is to show an architectural vision, not a technical solution which, by definition, has not yet been developed. The risk of showing too much detail in a pre-design presentation is that the audience may become focused on particular elements, losing sight of the overarching conceptual point of the presentation. At worst, this may result in the audience dismissing the concept outright. Another risk of showing an apparently complete design at the pre-design stage is that the audience may develop false expectations for the eventual result. The usage of precedent images can be helpful in composing a pre-design presentation which shows the architectural aspirations of a project without constraining the eventual design.

Project promotion may occur through many different media, including websites, publications, press releases, brochures, sales events and tradeshows. It is less likely that the architect will lead these efforts, but it is very likely that they will be requested by the client to provide supporting visual materials and technical data.

Architects may also be asked by corporate clients to develop branding and graphic identity. This could take the form of designing websites, logos, stationery, furniture, menus, advertising, and products.

Public Engagement

Engaging the public is often a necessary step in performing such pre-design services as feasibility studies, land-use rezoning, and master planning. It is also often required for, or at least beneficial to, obtaining development permits during later phases of design.

Done well, public engagement allows neighbours and other community members to provide meaningful input to the aspirations of the project, which can then be incorporated into the eventual design of the building or facility. If not executed carefully, however, public engagement can result in vague uninformative data, unrealistic expectations, and opposition to the project.

Larger clients may have their own in-house resources to lead public engagement. Other times the architect may be solely responsible for this work. Engagement may include presentations, surveys, open houses, town halls and design charrettes. Any architect unfamiliar with the “art” of public engagement should consider enlisting experts who specialize in the field, especially on larger or contentious projects.

Design Competitions and Proposal Calls

To successfully complete pre-design and move into design, a client should have a sense of how the design (and construction) resources will be procured. The pre-design architect can provide the client with a summary of procurement options, and a recommended strategy. The pre-design architect may continue with the client into a contract for the design and construction phases, or the client may proceed with a different architect.

A client may choose to procure a design architect via a design competition or proposal call, which the pre-design architect may assist a client with. In these cases, the pre-design architect will employ their industry knowledge to help with work such as:

- drafting scope and eligibility requirements;

- developing short lists and invited lists;

- producing the competition terms and conditions and/or requests for proposals;

- preparing for, and conducting, information sessions for proponents;

- establishing a jury and the criteria to judge proponents;

- pre-screening submitters for eligibility;

- judging and awarding;

- preparation of contractual agreements.

It is general practice for an architect who has participated in establishing a competition or proposal call to be ineligible as a proponent, so this should be considered prior to accepting such work.

Proponent architects responding to competitions and proposal calls should consider the amount of resources these endeavours can consume, and the likelihood of winning. They should also check with their local architectural association regarding any regulations or advisories concerning participation.

See also Chapter 4.1 – Types of Design-Construction Program Delivery for more discussion on construction procurement methods, and Chapter 3.3 – Brand, Public Relations and Marketing for more information on competitions and proposals.

References

Bens, Ingrid. Facilitating with Ease, 4th Edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2017.

Brauer, Roger L. Facilities Planning: The User Requirements Method, 2nd Edition. American Management Association, 1992.

International Facility Management Association. “Facility Condition Index (FCI).” Facility Management Glossary, International Facility Management Association. https://community.ifma.org/fmpedia/w/fmpedia/2459, accessed March 8, 2020.

Hanscomb. Yardsticks for Costing: Cost Data for the Canadian Construction Industry, Toronto: Gordian, 2020.

Hershberger, Robert. Architectural Programming and Predesign Manager. New York, NY: Routledge, 2015.

Hughes, Will, Debbie Ancell, Stephen Gruneberg, and Luke Hirst. “Exposing the Myth of the 1:5:200 Ratio Relating Initial Cost, Maintenance and Staffing Costs of Office Buildings,” in Khosrowshahi, F (ed.) 20th Annual ARCOM Conference, 1-3 September 2004, Heroit Univerdity. Association of Researchers in Construction Management, Vol. 1, 373-81.

Palmer, Mickey A. The Architect’s Guide to Facility Programming. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Inc., 1981.

Peña, William M. and Steven A. Parshall. Problem Seeking: An Architectural Programming Primer, 5th Edition. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2012.

Additional References

Bouvier, Pierre. “Les institutions muséales. Rénovation Construction Agrandissement. Guide pratique.” SSIM - Service de soutien aux institutions muséales; Direction du patrimoine et de la muséologie; Ministère de la Culture, des Communications et de la Condition féminine, octobre 2010. https://www.mcc.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/documents/publications/ssim-guide-architecture-inst-muse.pdf, accessed April 28, 2020.

Cherry, Edith. Programming for Design: From Theory to Practice. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 1998.

Duerk, D.P. Architectural Programming, Information Management for Design. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1993.

Kumlin, R. Architectural Programming: Creative Techniques for Design Professionals. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Inc., 1995.

Preiser, W.F.E., editor. Professional Practice in Facility Programming. New York, NY: Routledge Revivals, 2016.

Preiser, W.F.E., editor. Programming the Built Environment. New York, NY: Routledge Revivals, 2015.

Articles, Research Papers and Web References

Barekati, Ehsan, and Mark Clayton. “A Universal Format for Architectural Program of Requirement - A prerequisite for adding architectural programming information to BIM data models.” Texas A&M University, in Fusion, Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe, 385-394, Vol. 2, eCAADe: Conferences 2. Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, UK: Northumbria University, 2014. http://papers.cumincad.org/data/works/att/ecaade2014_202.content.pdf, accessed April 27, 2020.

Cherry, Edith, and John Petronis. “Architectural Programming.” Whole Building Design Guide, November 2, 2016. https://www.wbdg.org/design-disciplines/architectural-programming, accessed April 27, 2020.

Saly, Justin. “Functional Programming.” Examination for Architects in Canada, June 7, 2010. http://www.exac.ca/fileadmin/documents/pdf/en/ARE-Functional_Programming-2010_ENG.pdf, accessed April 27, 2020.

WBDG Functional/Operational Committee. “Functional/Operational.” Whole Building Design Guide, October 6, 2018. https://www.wbdg.org/design-objectives/functional-operational, accessed April 27, 2020.

WBDG Functional/Operational Committee. “Account for Functional Needs.” Whole Building Design Guide, October 7, 2018. https://www.wbdg.org/design-objectives/functional-operational/account-functional-needs, accessed April 27, 2020.

WBDG Functional/Operational Committee. “Ensure Appropriate Product/Systems Integration.” Whole Building Design Guide, October 7, 2018. https://www.wbdg.org/design-objectives/functional-operational/ensure-appropriate-productsystems-integration, accessed April; 27, 2020.

WBDG Functional/Operational Committee. “Meet Performance Objectives.” Whole Building Design Guide, October 7, 2018. https://www.wbdg.org/design-objectives/functional-operational/meet-performance-objectives, accessed April 27, 2020.

WBDG Project Management Committee & Commissioning Leadership Council. “Determine Project Performance Requirements.” Whole Building Design Guide, November 15, 2016. https://www.wbdg.org/building-commissioning/determine-project-performance-requirements, accessed April 27, 2020.

Governmental Guidelines and Similar References

Drolet, Céline. “Méthodologie - Programme fonctionnel et technique. Répertoire des guides de planification immobilière.” Direction des communications du ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux, Québec, 2014. http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/fichiers/2014/14-610-03W.pdf, accessed April 27, 2020.

Infrastructure Alberta. “Appendix 7 - Functional program framework for health capital projects.” 2013. http://www.infrastructure.alberta.ca/content/docType136/production/Appendix%207.pdf, accessed April 27, 2020.

Existing Building Condition – Checklists

Institute for Building Research. “Protocols for Building Condition Assessment.” National Research Council Canada, September 1993. https://nparc.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/fra/voir/texteint%C3%A9gral/?id=1cc8c8a9-b8de-4fe4-a928-3632c5466ffd, accessed April 27, 2020.

Institut de recherche en construction. “Protocoles de vérification technique des bâtiments.” Conseil national de recherches Canada, septembre 1993. https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=ad780143-a1c6-4ba7-9703-59a97fd598a8, accessed September 15, 2020.

ASTM Subcommittee: E50.02. “ASTM E2018 – 15 Standard Guide for Property Condition Assessments: Baseline Property Condition Assessment Process.” ASTM International, 2018. https://www.astm.org/Standards/E2018.htm, accessed April 27, 2020.

ASTM Subcommittee: E06.55. “ASTM E2270 - 14 Standard Practice for Periodic Inspection of Building Facades for Unsafe Conditions.” ASTM International, 2019. https://www.astm.org/Standards/E2270.htm, accessed April 27, 2020.

Appendix

- Appendix A – Checklist for Physical, Environmental and Climatic Factors

- Appendix B – Checklist for Information for Topographical and Legal Land Surveys

- Appendix C – Checklist for Environmental Site Assessments

- Appendix D – Checklist for Geotechnical and Soils Reports

- Appendix E – Checklist for Facility Accessibility Surveys

- Appendix F – Checklist for Archaeological Surveys

- Appendix G – Checklist for Site Energy Studies

- Appendix H – Checklist for Traffic Impact Assessments and Parking Studies