Definitions

Accounts Payable: A record of accounts of money payable to consultants and to other suppliers for expenses.

Accounts Receivable: A record of professional fees and disbursements which have been invoiced.

Aging Reports: A record of invoices due and past due. This can be for both accounts receivable and accounts payable.

Amortization: See Depreciation.

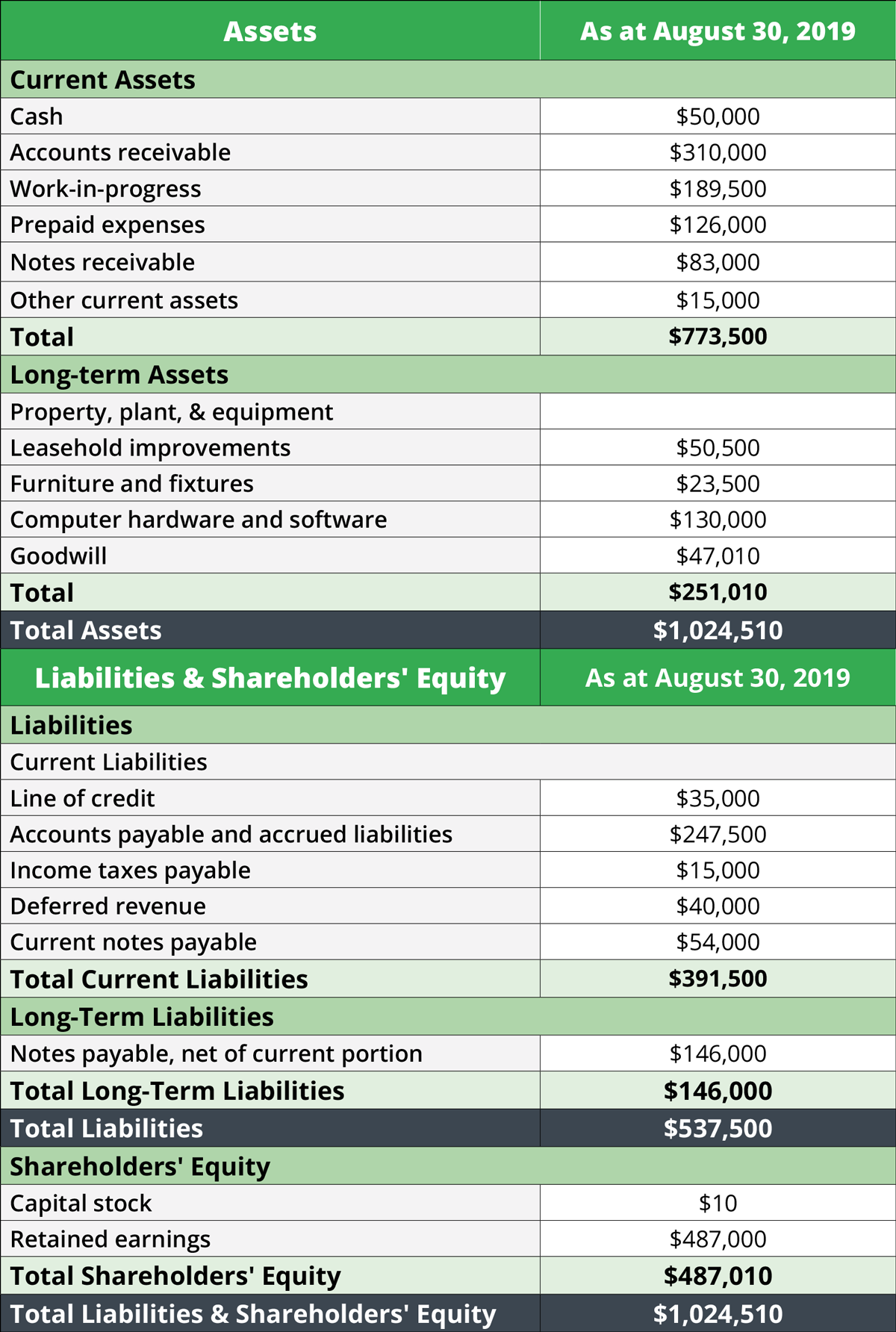

Average Collection Period (ACP): Accounts receivable divided by gross revenue x 365. This is a key factor in liquidity. It measures the average number of days it takes to receive payment from the invoice date. The fewer the number of days, the better the company can convert collections into cash, thereby strengthening its financial position and liquidity. Using the statement of income and expenses in Table 1 and the balance sheet in Table 2, the ACP = $310,000 / $981,000 x 365 days = 115.3 days.

Bad Debt: Recorded on the income statement, the amount of accounts receivable that will be not collected from clients.

Balance Sheet: A record of all assets, such as bank funds, receivables, furniture, computer equipment; all liabilities, such as accounts payable and loans; and retained earnings, which state the financial position of the practice at a particular point in time.

Cash Book: A record of the day-to-day cash position of the practice using the cash accounting method. All transactions are entered and a running balance is calculated.

Cashflow: Cash and other liquid assets to meet current payroll, consultants’ fees, and other overhead expenses.

Current Assets: Includes items from the balance sheet that are cash and cash equivalents, such as accounts receivable and short-term investments — any line items that can be converted into cash within a year.

Current Liabilities: Usually includes liabilities that are due within a year, for example, accounts payable, taxes, wages, insurance.

Current Ratio: The formula is current assets divided by current liabilities. It measures the liquidity risk of the business and its ability to generate cash to meet short-term financial commitments such as payroll, subconsultant fees, line of credit, etc. This ratio also helps in understanding how cash (or cash equivalent) rich the company is. For example, a ratio of 1:1 indicates that for every $1 in liabilities, the business has $1 in assets to pay it. Using the balance sheet in Table 2, the current ratio is $773,500 / $391,500 = 2.0.

Debt to Equity Ratio: The formula is total liabilities divided by shareholders’ equity. This ratio measures whether the business is comfortable handling its debt obligations. If debt is higher than equity, it signals that the business is overburdened by debt. Using the balance sheet in Table 2, the debt to equity ratio is $537,500 / $487,010 = 1.1.

Depreciation/Amortization: The rate by which capital assets may be depreciated according to government tax regulations (referred to as capital cost allowance). It is also used by accountants to account for the loss in value of an asset as it ages. Because most fixed assets have value longer than a year, depreciation is a way of expensing a portion of the fixed asset each year.

Direct Personnel Expense (Direct Labour Cost): The salary of a staff person engaged on the project plus the cost of such mandatory and customary contributions and employee benefits as employment taxes and other statutory benefits, insurance, sick leave, holidays, vacations, pensions, and similar contributions and benefits.

Disbursement Record: A record of billable reimbursable expenses.

Fiscal Period: A 12-month period for which financial records start and end. (Previously, it was an advantage for a fiscal year to end early in the calendar year. Legislation now requires most professionals to pay taxes based on a calendar year, which encourages the fiscal year-end to correspond to the end of the calendar year.)

General Ledger: A record of all accounts, including receivables, payables, income and expenses, payroll, tax payments, disbursements, etc.

Labour Multiplier (Net Multiplier): The formula is net revenue divided by direct labour costs. It represents the actual net revenue generated by the firm expressed as a multiple of total direct labour costs. This multiplier shows the return on the investment made in direct labour costs.

Multiplier: A percentage or figure by which direct personnel expense is multiplied to cover overhead expenses and profit. (The result is used to establish a charge-out, or billing rate.)

Office Overhead: Includes expenses for rent and utilities, office supplies, computer maintenance, automobile expenses, promotion and advertising, books and subscriptions, annual dues, leasing expenses (except as noted below), postage, delivery services, bank charges, interest charges, business taxes, donations, seminar and training expenses, and depreciation. [Note: Consultant expenses that are required to provide architectural services are excluded from overhead. However, other consultants such as legal, accounting, and marketing are included in overhead expenses. The purchase or lease of major expenditure items such as automobiles, computers, or office renovations is charged as office overhead only to the extent that such expenses can be depreciated in accordance with tax regulations.]

Overhead Rate: The formula is total overhead including indirect labour divided by direct labour costs. This is a key rate to measure efficiency. The lower the overhead rate, the higher the profit margin.

Payroll Burden: Includes required contributions by the employer (statutory benefits), including Employment Insurance (EI), Canada Pension Plan/Québec Pension Plan (CPP/QPP), health taxes, and workers compensation, in addition to discretionary benefits such as insurance and pension plans, and bonuses.

Payroll Records: A record of salaries, taxes due and paid, and payroll burden for each employee.

Profit: An excess of revenue over expenses.

Profit Margin: The formula is net profit divided by net revenue x 100. This is one of the most important ratios to analyze the overall financial health of a firm. It measures in percentage terms how much profit is left over after all expenses are accounted for (including taxes, interest and depreciation). The higher the percentage, the more profitable the firm is.

Project Cost Control Chart: A financial record of each project, which includes professional fees, consultants’ fees, staff time expended, budgeted time, expended payroll, and profit and loss for each phase of the work.

Staff Utilization Records: Identifies monthly and year-to-date hours spent by each staff person on direct labour for projects, as well as hours for vacation, holiday time, sick leave, and miscellaneous overhead duties. The records should indicate a percentage of direct (billable) to indirect (non-billable) time. These records are used to develop billing rates for individual staff members, as well as for short- and long-term planning.

Statement of Income and Expenses: A report, often prepared monthly, documenting all income, all expenses, and the resulting profit or loss.

Tax Records: Includes personal income taxes, corporate taxes, and GST or HST.

Work-in-Progress (WIP): Work underway or complete but not yet invoiced.

Introduction

This chapter will provide a short introduction to financial management, an essential activity for every architectural practice. Financial management is one of the most important responsibilities of owners and architects in managerial positions. It provides a framework for pursuing synergy between the studio architectural responsibilities and the financial resources of the firm. Good financial management systems will help the practice reach its strategic objectives as well as its financial goals.

Profit

The practice of architecture is a business, and the goal of every business is to achieve and sustain profits. The success of the business depends on the ability to continuously generate profits to attract talent, partners and/or external investors, secure bank loans, and grow its operations. Financial management helps to maximize profit, and helps the firm develop strategies to remain profitable.

A profit is required in order to:

- build a reserve for cyclical downturns;

- invest in additional resources (purchase assets, hire new employees, expand operations);

- pay out retiring or dismissed employees and partners;

- build a successful financial history for borrowing funds;

- invest in research and professional development;

- fund incentive programs;

- reward owners for efforts expended and risks taken;

- attract investors

Distribution of Profits

Profits are simply revenue minus expenses. Once tax is accounted for, the company owners or management decides whether the profits are distributed (to owners or shareholders) or retained in the business. Appropriate financial planning should always include a reasonable profit, and it is advisable to set aside a percentage of the profit as a capital reserve. Proper tax planning will affect the amount of profit withdrawn from the practice and this amount may be distributed to owners or shareholders (if the practice is incorporated). After a percentage of the profit is set aside as a capital reserve, the balance may be distributed to shareholders (if the practice is incorporated) and to staff. In “lean” years, the capital reserve may be very little or non-existent; however, in “very profitable” years, the capital reserve could be as much as 50% of the practice’s profit.

Distribution of incentive bonuses to staff should be based on the practice’s established policy and on factors determined in a performance review, such as:

- ability;

- productivity;

- behaviour;

- professional growth.

See Chapter 3.6 – Human Resources, for information on performance reviews.

When the practice is owned by shareholders or partners who have invested capital in the practice, their investment should earn interest at the bank’s prime rate of interest, plus an additional percentage which represents a reasonable return for their financial risk.

Financial Planning

Financial planning should be part of the strategic plan of every architectural practice. The financial plan is a set of guidelines, not rules, based on trends and the best estimates. The revenue forecast is the starting point, and it serves as the basis for other line items such as:

- strategic goals and objectives of the practice;

- revenue projections;

- target for profit;

- budgets for overhead expenses, including any new capital expenditures;

- staffing plans, including number and type of staff.

This financial plan should identify income and expenses projected for any new direction for the practice, for example, the delivery of new services and the associated costs required to:

- hire staff;

- undertake research and marketing;

- buy or lease new premises;

- finance professional development and training;

- purchase or lease new furnishings, equipment, and software.

If the practice must downsize as a result of an economic downturn or for another reason, a financial plan is necessary to resolve issues, such as:

- relief from a lease for office space;

- the need to restructure (see also Chapter 3.6 – Human Resources).

Short-term financial planning, usually called budgeting, covers a time period of 12 months primarily because of the requirements for annual financial statements and the normal fiscal year. Some firms divide the year up into 13 equal periods of 4 weeks each. Budgets show projected income, expenses, and profit. They should be constantly monitored, usually on a monthly basis. The budget should also record the previous year’s revenue and expenses, as well as the difference between the budgeted and actual revenue and expenses.

Projected income includes:

- work-in-progress;

- anticipated professional income (based on the previous year’s records);

- other anticipated income.

Projected income must be adjusted to account for the current and projected economy in the design-construction industry and any extraordinary conditions.

Projected expenses include:

- estimated expenses (based on the previous year’s records);

- changes in expenses which have occurred or will occur (such as staff pay raises or rent increases);

- increased expenses to meet long-range planning targets, for example:

- increased staff requirements;

- increased office space or other overhead expenses;

- software and hardware investments.

Profits are usually estimated as a percentage of projected revenues and should be identified in relation to the long-range financial plan. An architect can use Table 7: Annual Budget Calculation in Appendix A at the end of this chapter to help prepare an annual budget.

Both budgeting and long-range financial planning should include appropriate salaries — commensurate with ability and experience — for principals, directors and shareholders.

Accounting

Accounting is the process of recording financial transactions, assessing the information and summarizing it to produce financial statements. Accounting provides information useful for making financial and economic decisions. There are two types of accounting:

- internal accounting;

- external accounting.

Internal accounting, sometimes called management accounting, is done within the architectural practice — often by staff, a bookkeeper, or other professional such as an accountant.

External accounting, usually performed by an independent accountant, frequently includes the preparation and examination of financial statements in order to express an opinion on the financial position of the practice. This can be in the form of an audit, a review, or a compilation, depending on which criteria the company falls in as stated in corporate bylaws.

An audit is an independent and objective examination of accounting records and other necessary documentation in order to express an opinion on the fairness of a balance sheet and other financial statements. An audit provides a “reasonable assurance” that the financial statements of the business are free of material misstatements and are in accordance with Canadian generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP).

A review is less extensive (and less expensive) compared to an audit. It provides a lower level of assurance that the financial statements are free of material misstatements.

A compilation is the lowest level, where the external accountant compiles the financial data from the company’s system and puts together the financial statements. In compilation, the financial data is not examined in detail.

Banks typically require the middle level of assurance, a review. It is best to check with your accountant as to whether your business qualifies for a review versus an audit when working to secure external funding.

Accounting Systems

Records of accounting are statutory requirements. The better and more accurate the records, the greater the opportunity for more accurate long-range planning and budgeting and, in turn, the greater the opportunity for profit. When setting up a new company, the firm needs to decide on an accounting period (fiscal year) and how to record transactions.

There are two different systems of accounting to record transactions:

- Cash basis system;

- Accrual basis system.

If you use an accounting software, you’ll be asked to select your accounting method, cash or accrual, to record transactions. Architecture businesses are required by the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), by Accounting Standards for Private Enterprises (ASPE), and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) to follow the accrual basis for accounting and tax returns.

Accrual System

The accrual system records all income — including work-in-progress — and expenses as they occur in the general ledger. It shows the current financial position of the architectural practice, usually on a monthly basis.

Using the accrual system, two types of financial reports are prepared:

- statement of income and expenses (also known as Income Statement or Profit and Loss Statement);

- balance sheet (also known as Statement of Position).

Financial Statements

Balance Sheet

Usually an accountant or bookkeeper will use accounting software to prepare financial statements using the following architect-supplied information:

- the general ledger;

- payroll records;

- statements of income and expenses;

- other information.

It is important that any architect involved in running a practice, whether a first-time associate, a principal, a partner, a shareholder or a sole proprietor, understand the three foundational elements to their business, which are:

- balance sheet;

- income statement;

- cashflow.

The financial health of a business is analyzed by financial statements and ratios. These three financial statements have a standard format, regardless of whether a company is a start-up or a major corporation.

The balance sheet is the most important financial statement. It is a summary of the company’s general ledger. The basic formula of the balance sheet is:

Assets = Liabilities + Owner’s Equity

Balance sheets are important for the monitoring of assets (what the business owns) and loan commitments (what the business owes). This means everything from the cash the firm has in the bank to amounts that are owed to subconsultants, creditors and employees. In addition, it includes the owners’ investments and monies drawn from the business. The balance sheet shows the financial position of a company at a given period and answer three questions: Who owns the business? How liquid is the business? And how lean or fat is the business?

A balance sheet and a 12-month statement of income and expenses are sometimes required by:

- banks, for a line of credit or a loan;

- professional liability insurers;

- governments, for taxation purposes;

- other architects, when restructuring the ownership of the practice or selling the practice.

Income Statement

The income statement is also referred to as a Profit and Loss Statement, a Statement of Revenues over Expenditures, and an Operating Statement. This statement tells a story about profitability and how the profit for the given period was earned. It is a detailed explanation of the increase in the owner’s equity on the balance sheet. The income statement’s primary focus is on profitability and growth.

An income statement provides:

- a summary of income, including work-in-progress;

- expenses incurred against all income, including work-in-progress;

- an accounting of profit or loss for the time period.

Regardless of the size and type of the business, the income statement follows a basic formula:

Income – Expenses = Profit or Loss

Income is also called revenue or architectural fees. The total income of a business is the sum of all sources of revenue in each period. Expenses are the costs (labour, overhead) of generating the income. Profit or loss is what is left after subtracting all expenses from income.

The statement has three principal components:

- income;

- expenses;

- profit.

Income includes:

- professional fees invoiced [Note: Fees for consultants should be retained and may be put into a separate account until due and payable];

- work-in-progress [Note: If all accounts are invoiced monthly, reporting of work-in-progress is not necessary];

- reimbursable expenses invoiced;

- interest income;

- miscellaneous income.

Income recording can also be subdivided to identify income from separate offices or separate areas of practice, or by individual projects. Expenses include:

- salaries [Note: This can be subdivided into categories such as principals (partners or directors), professionals, technical staff, support staff];

- payroll burden;

- consultants’ fees;

- overhead expenses, subdivided by category.

The income statement is the primary measure of a firm’s performance, while the balance sheet shows a firm’s overall health.

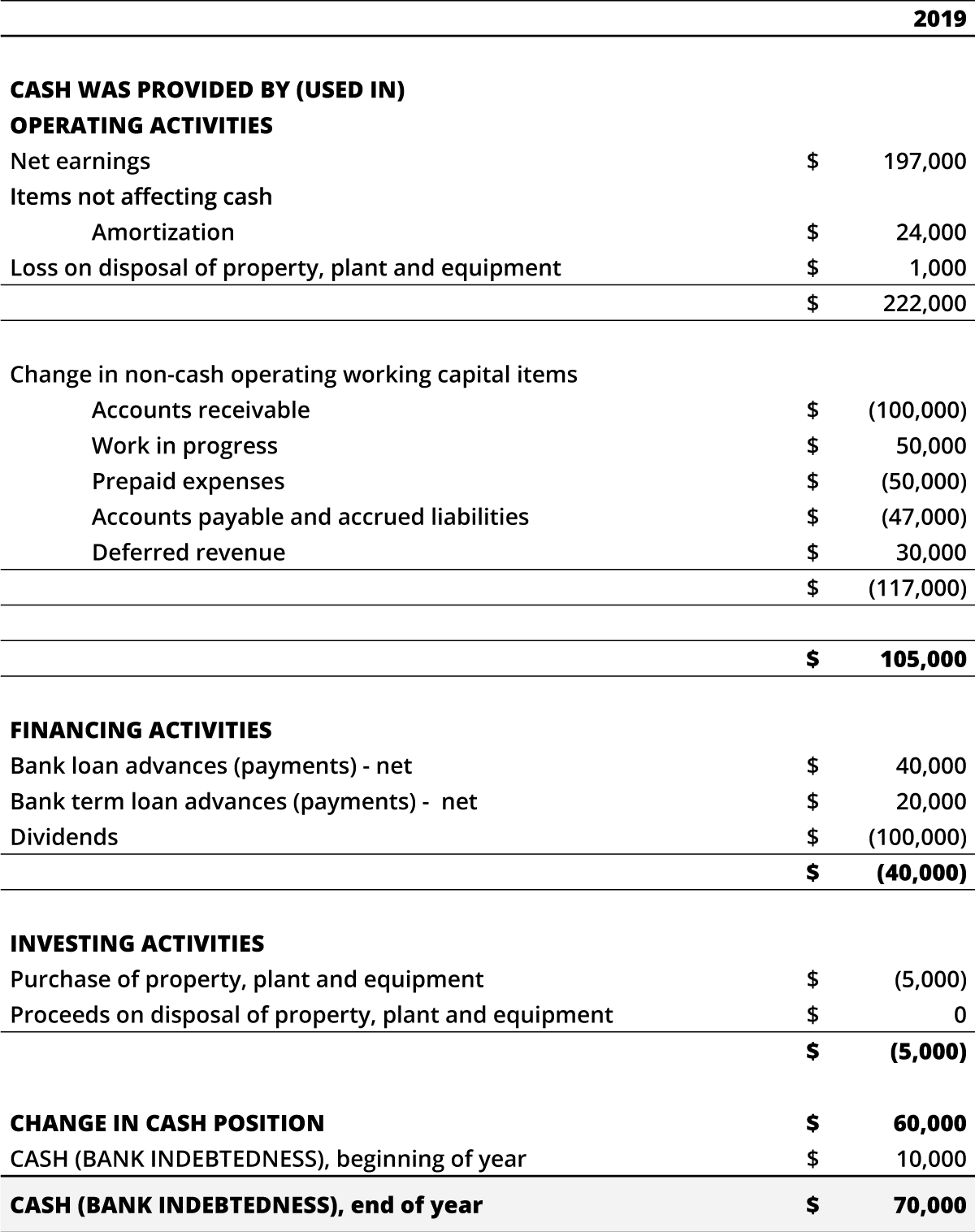

Cashflow

The Cashflow Statement is also referred to as a Statement of Changes in Financial Position. Cashflow is vital for the well-being of an architectural practice. Without a positive cashflow, a firm is forced to borrow money, or, in worse cases, it may not stay in business.

Cashflow relies heavily on a firm’s cash from fees, which in turn is impacted by a firm’s net income. The higher the revenues and the lower the overhead, the more efficient revenues are as drivers of cashflow.

Implementation of cashflow management technology and project management software can help a firm be financially successful.

The cashflow statement is a detailed explanation of the change in cash on the balance sheet. It is like a bank account statement: it states how much cash was available at the beginning of the period, how much new cash was collected, how much cash was paid out, and the ending balance of cash. The cashflow statement is used to understand how to realize the profit into cash.

It is important to note that a company can be very profitable on the income statement but at a high risk if it does not have enough cash to pay for operations. Profit and cash are not the same thing.

All three financial statements tell a story about the business. Most accounting software will provide this information at regular periods.

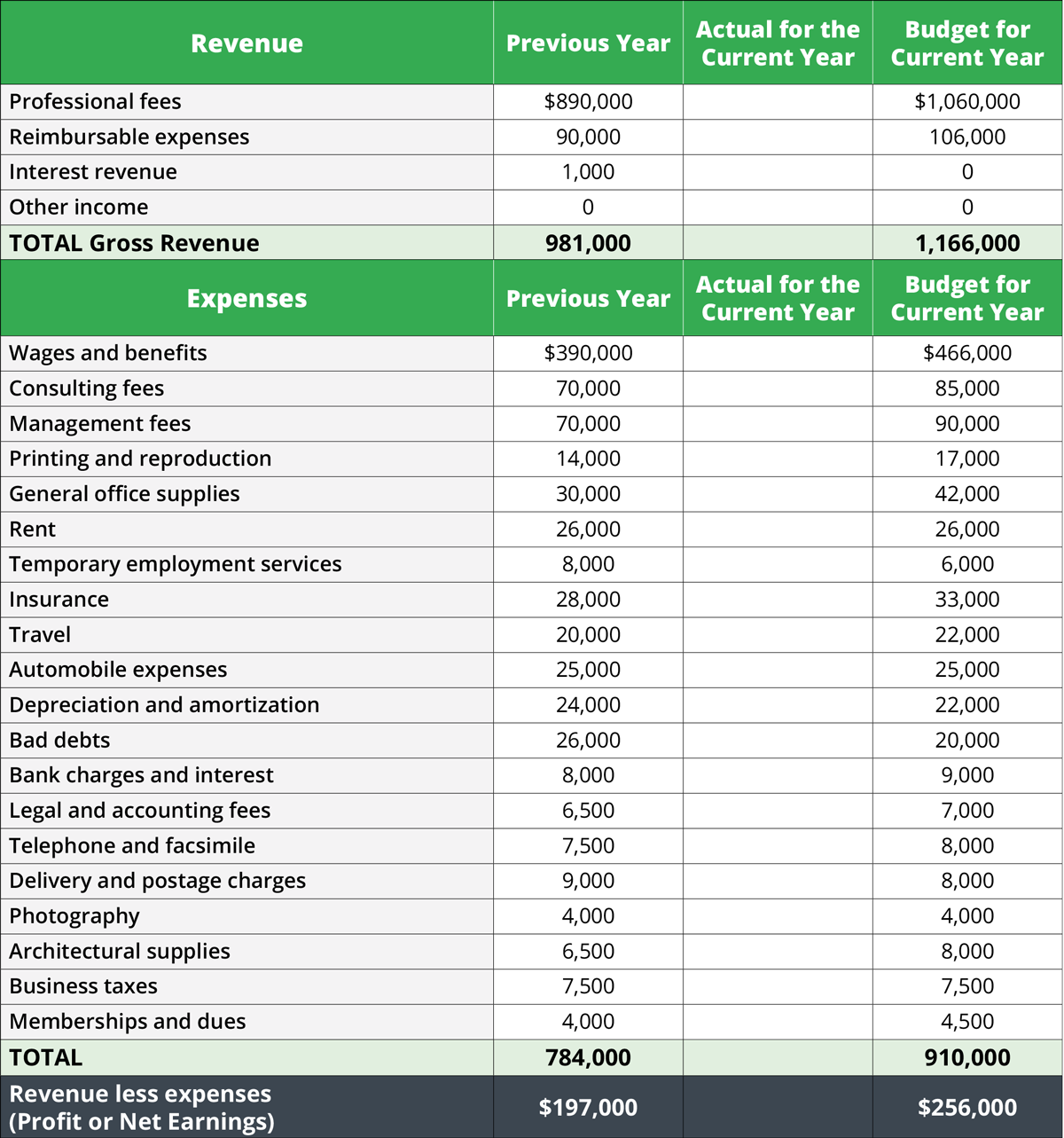

See Table 1 for a typical “Statement of Income and Expenses” for a medium-sized architectural practice. This statement would be prepared after all financial records are recorded for the specific period. The left-hand column reflects a history of the practice’s financial activities. The right-hand column illustrates a budget or future financial activity based on anticipated revenue and expenses. The increased revenues may be predicted because of recently acquired projects or a buoyant economic environment. Similarly, an increase is projected for wages and benefits as more staff will be required to undertake the increased workload.

Other costs are projected to increase proportionately because of increased staff and work.

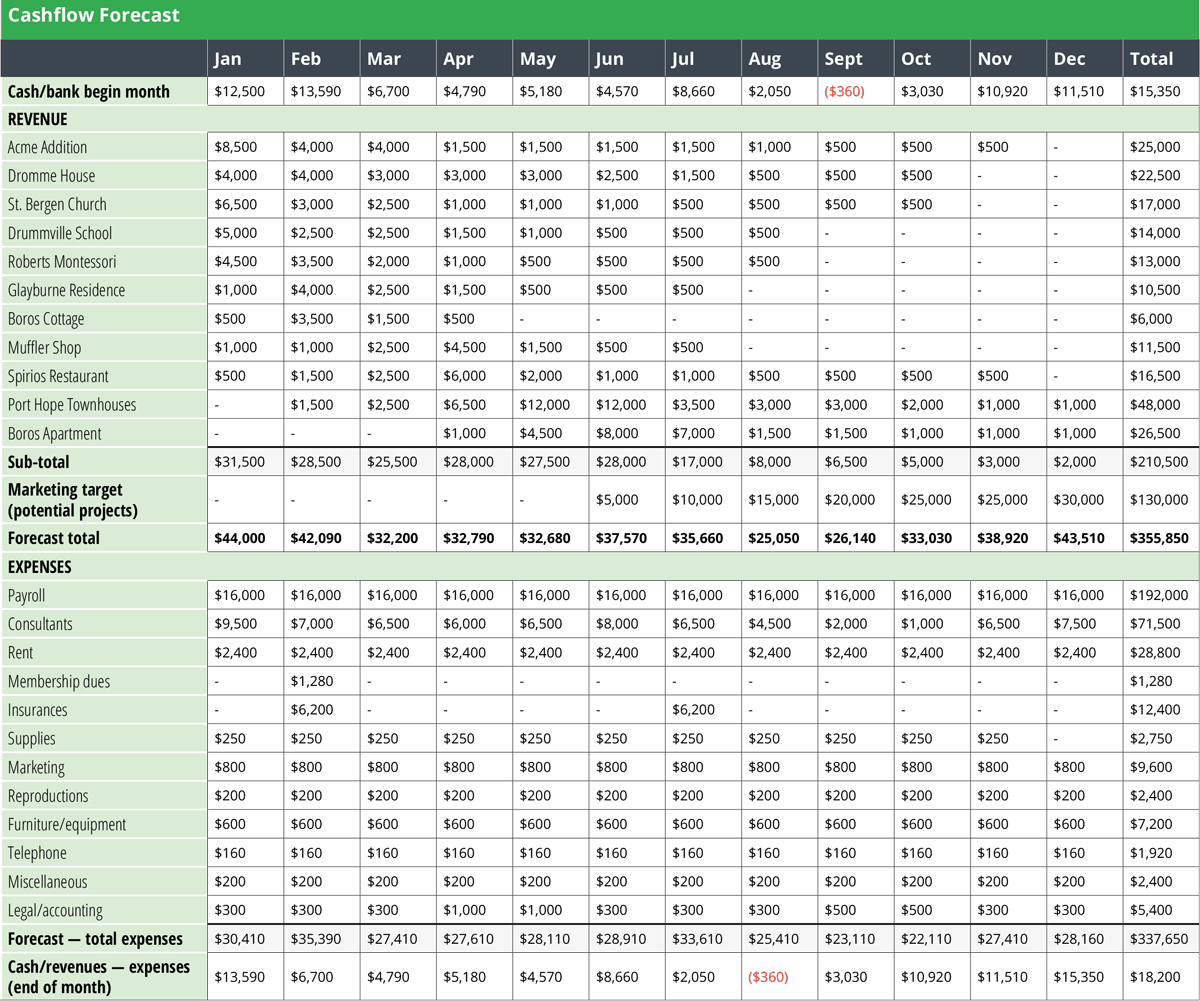

Cashflow Forecast

A cashflow forecast is helpful in projecting the practice’s cash position over a 12-month period. Such a forecast is needed to determine how much cash will be required to meet expenses in the short term and any additional requirements for working capital from a line of credit.

The forecast should reflect the following on a monthly basis:

- operating funds required;

- line of credit required;

- relationship between revenues and operating expenses.

Several computer software programs are available to assist in the preparation of these forecasts.

In preparing a cashflow forecast, a client’s payment history should be considered because many clients take longer than 30 days to pay invoices. The forecast should be monitored every month by comparing actual revenues and expenses with those forecast. The forecast should be updated quarterly. A sample cashflow forecast is shown in Table 6.

Table 1: Sample Statement of Income and Expenses

Table 2: Sample Balance Sheet

Table 3: Sample Cashflow Statement

Financial Professionals

Finance professionals can be bookkeepers, non-certified accountants, or Chartered Professional Accountant (CPA), who all can work with financial data. A CPA is a licensed professional who adheres to certain professional standards and the use of established accounting principles. An accountant should respond to the needs of the practice by advising on the type and extent of financial services required for the size and complexity of the practice.

The accountant’s task will be easier, resulting in lower fees for accounting services, if the architect practices good financial management and keeps proper books of account, including:

- general ledger;

- accounts payable;

- accounts receivable;

- payroll records.

Accountants are familiar with most software programs and should be able to provide advice on the software suitable to the size and complexity of the practice. Generally, all payroll software should be for use in Canada.

When engaging an accountant, as with all professionals, it is necessary to establish a clear understanding of the following:

- the services to be provided;

- the “deliverables” or financial reports;

- the professional fee.

The architect involved in the financial aspects of the practice should develop a rapport with the accountant. The relationship should be one that is built on a foundation of trust, transparency and providing you proactive advice. When that level of comfort or service no longer exists, it may be a good practice to request proposals from other accounting firms to compare services and value.

Architect practices are not required to hire only CPAs. Depending on the size of the firm, the practice can hire bookkeepers or non-certified accountants to complete a wide variety of responsibilities, such as preparing internal financial reports, recording day-to-day transactions, invoicing clients, managing collections, performing account reconciliations, and maintaining records. These individuals may be licensed accountants or equipped with education or experience in a related field.

The external CPA may also go over the accounts maintained by internal staff, and review or audit them to ensure that the records are accurate before finalizing the annual financial statements and filing taxes.

Bankers

It is also important to establish a professional relationship with a banker. Proper long-range financial planning and the establishment of a capital reserve should eventually enable the architect to avoid having to finance day-to-day operations. When funds for the operation of the practice are not required, it is possible to “tender” for the bank service fees by asking two or more banks to quote on the charges for various banking services. Instead of acquiring a short-term loan to finance operating expenses, many businesses negotiate a line of credit which can be used when and as required up to a limit arranged with the bank.

The best time to negotiate for a line of credit is when financing is not required. In this case, the cost is usually reasonable in the form of a low standby fee, and the line of credit will be in place when it is required. The interest rate quoted will probably be determined by the bank’s perception of the level of risk in financing the architectural practice. The interest rate charged by the bank will be expressed as the percentage over the “bank rate” or “prime rate.” (The prime rate is the fluctuating rate which banks charge their best customers.)

When the practice does need to borrow funds, the architect should provide complete records of past performance, plus detailed budgets and long-range financial plans. This information assists the banker in deciding on a line of credit for the practice. The amount of credit is usually a percentage of the accounts receivable and work-in-progress. If the amount requested is high, the bank may demand a higher percentage rate of interest over “prime” on the loan, and usually requires personal guarantees from principals, directors or major shareholders.

A well-prepared cashflow projection (see Table 6) for the year ahead may be necessary to successfully negotiate a line of credit with the bank. An accountant can provide advice on the information required by banks for approving loans and a line of credit.

Information for Financial Management

Accurate and complete financial information can assist the architect in preparing accurate budgets, and in monitoring and controlling expenses incurred in providing architectural services. Various forms for financial management purposes are provided in Chapter 3.11 – Standard Templates for the Management of the Practice, including the following:

- Invoice;

- Fee calculation sheet;

- Project cost control chart;

- Time report;

- Expense claim form;

- Ratio analysis.

Fee Calculation

When determining fees for services, the architect should identify and determine the following:

- each component of the services to be provided;

- the cost of production for each component (including direct and indirect costs);

- the profit margin to be achieved.

All projects should generate a profit. The only possible exception to this principle is when the loss is part of a long-range or short-term strategy (such as undertaking a new and unknown building type). Such a loss can be endured only if:

- the loss is clearly forecast;

- adequate reserves are available to underwrite the loss.

The various methods of compensation, or methods of fee calculation, are outlined in Chapter 3.9 – Architectural Services and Fees.

Regardless of which method is selected, the architect should also estimate the amount of time needed to complete all the required tasks for the project, as well as the associated costs, by using staff “billing rates” (also called charge-out rates). This estimate can be used to check whether the proposed fee will be adequate to complete all the services to be contracted, and if a profit can be realized.

For example, when estimating the fees for schematic design, the architect should:

- calculate how many hours it will take to develop one schematic design, by whom, and at what billing rate;

- estimate the time to develop subsequent designs using the same procedure, as it may be necessary to undertake two or three schematic designs;

- define in the agreement how many different alternative schematic designs will be developed;

- quote an additional fee for each subsequent alternative beyond the number quoted.

A “Fee Calculation Sheet” is provided in Chapter 3.11 – Standard Templates for the Management of the Practice, for this purpose.

Adequate profit margins may not be achieved if:

- additional time on the project is required due to unexpected circumstances;

- additional time is not billable as an “additional service”;

- too low a fee was offered or negotiated;

- the time required to provide adequate services was incorrectly estimated;

- the project was poorly managed.

[Note: Additional time is often required when the project is a building type with which the practitioner is not familiar.]

Billing Rates

RAIC Document Six: Canadian Standard Form of Contract for Architectural Services defines “direct personnel expense” and provides the opportunity to invoice for services using multipliers when the fees are charged on an hourly basis.

Establishing billing rates is becoming more complex in today’s competitive business environment. Billing rates must include overhead costs, including:

- office rent and operating costs;

- equipment purchasing or leasing, and maintenance;

- secretarial, clerical, and bookkeeping services.

Some large offices may have several staff positions that contribute to office overhead; their services are not chargeable directly to clients.

The salaries and benefits of each employee in the practice are known factors and can be converted to an hourly direct personnel expense by dividing the annual salary-plus-benefits (as defined in RAIC Document Six) by the number of billable hours in a year. One method for determining the number of billable hours in a year is to multiply regular daily hours by 365 days and deduct the following:

- weekends;

- statutory public holidays;

- an allotment of time for vacations;

- an allowance for sick leave;

- an allowance for non-productive time.

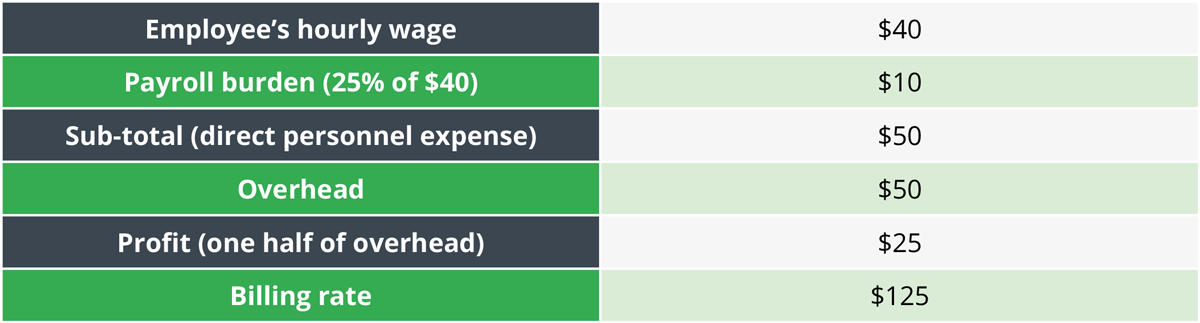

The billing rate is determined by applying a multiplier to the calculated hourly direct personnel expense. The multiplier is a factor which includes overhead plus profit and can vary from 1.8 to 3.0 depending on the size of the practice and its location (such as an urban centre with high costs).

A rule of thumb for calculating billing rates is to add 25% to the hourly rate for payroll burden, double the total to include overhead, and add 50% of the overhead for profit. This is the equivalent of a multiplier of 3.125 applied to the direct personnel expense.

Table 4: Billing Rate Calculation

The following is an example for an employee with an hourly wage of $40. In this example, the profit is 20%.

Architects that charge less than this formula limit growth and profits.

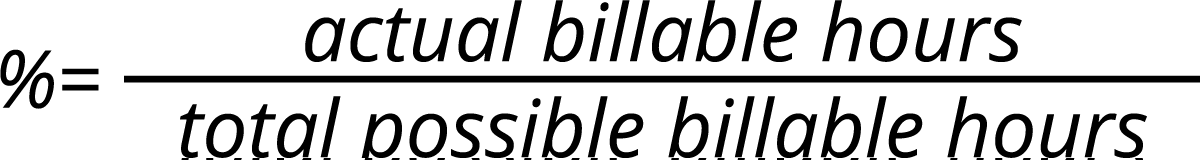

Utilization Factors

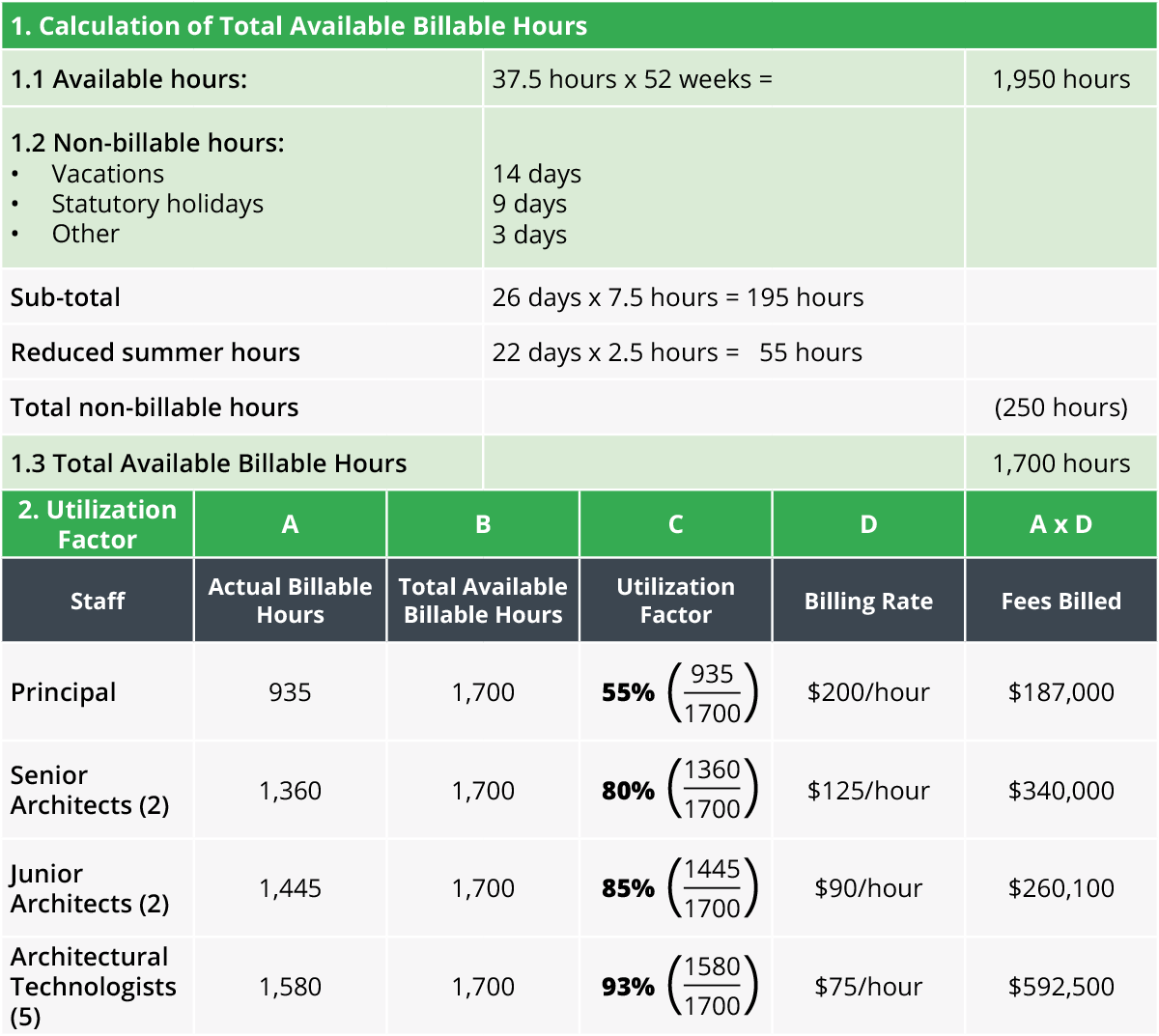

The percentage of billable hours as compared to the total hours of work in a year is called the “utilization factor.”

Utilization factor is a percentage determined by dividing the actual billable hours by the total billable hours possible.

Utilization factors may range from:

- 40-65% for principals;

- 70-80% for senior architects;

- 80-90% for project architects and technical staff.

Some personnel, such as those involved only in marketing or management, may have no billable hours and, therefore, no utilization factor. Utilization factors should be monitored regularly because of the direct correlation between high utilization factors and high revenue potential.

Table 5: Calculation of Utilization Factors

Project Cost Control Information

Information used to control project costs helps the architect to monitor income, expenses, and profit for each segment of the work on a project. The most practical means of monitoring and controlling project costs is through the project’s work breakdown structure. The work packages of the work breakdown structure are rolled up to the level of the project cost control accounts. A sample form, “Project Cost Control Chart,” is provided in Chapter 3.11 – Standard Templates for the Management of the Practice. This is a very basic chart; however, many software programs are available to assist the architect in monitoring project costs.

A project may be undertaken on a time and material basis. A system that shows the costs and effort hours for each work package, rolled up to the cost accounts, streamlines billing and communications.

Project cost control information should be monitored regularly to ensure that all tasks are completed within the estimated time and budget.

Time Reports

Time reports or time sheets should record enough information to provide summaries of time spent, on a weekly basis, for each task or portion of architectural service. The type of service and phase of the project should be accurately identified in order to measure budgeted time against actual time spent.

For example, if a fee for a schematic design has been budgeted at $12,000, and if one person with an hourly wage of $40 per hour will be assigned to produce this schematic design, the practice must budget $125 per hour, which calculates out to $12,000 ÷ $125 = 96 hours. If the individual has a utilization rate of 90%, then 90% of 37.5 hours per week = 33.75 hours of billable time. At a rate of 33.75 hours per week, it would take 96 hours ÷ 33.75 = 2.84 weeks (nearly 3 weeks) to complete the work. Reviewing the weekly time sheets in conjunction with the progress of the work will help to verify whether or not the design is advancing at approximately 33% per week.

A “Time Report” form is provided in Chapter 3.11 – Standard Templates for the Management of the Practice.

Invoicing

Useful tips on invoicing and collecting accounts are found in Chapter 3.8 – Risk Management and Professional Liability.

Financial Management and Ratio Analysis

Part of financial management is to track key performance indicators or ratios to analyze the financial performance of the business in terms of profitability, efficiency, risk, liquidity, effectiveness and growth. Ratios can also be used for trend analysis or comparative benchmark analysis to put a company’s financials into perspective. These ratios are calculated using the financial statements: balance sheet and income statement.

Common ratios for architecture business are:

- profit margin;

- overhead rate;

- labour multiplier (net multiplier);

- utilization rate;

- average collections period;

- current ratio;

- debt to equity ratio.

Some of these ratios are tools that banks and potential investors turn to when analyzing the company’s strengths and weaknesses. It is important to note that financial ratios can be reliable if the data itself is accurate and reliable.

Descriptions and formulas for the above are provided in the Definitions section of this chapter.

Other Financial Management Issues

Compensation

Ideally, compensation for all professionals in an architect’s office should be similar to compensation paid in other professional practices, assuming similar levels of responsibility as well as similar time and energy expended. In reality, all staff — including senior, junior, and intern architects; technical staff; and support staff — are compensated based on market conditions. Compensation also includes comfortable working conditions and professional career opportunities and challenges.

Surveys and information on standard levels of compensation are available from:

- federal government surveys;

- surveys by professional associations;

- surveys by architectural journals;

- an exchange of information with other architectural practices.

Proper financial management and current statistics enable the architect to properly compensate staff, thereby helping to increase productivity.

Tax Planning

Accounting advice should be sought for proper tax planning. The financial management of an architectural practice must consider the following taxes:

- Goods and Services Tax (GST), or Harmonized Sales Tax (HST) in some provinces, must be collected on all income. The total amount collected is reduced by the amount of GST/HST paid to vendors. The difference due to the government is usually paid quarterly.

- Employees’ income tax is deducted by the practice for every employee for every pay period. Payment is made to the federal government at intervals determined by the pay period. Income tax deductions include provincial income taxes as well as federal income taxes, CPP, and EI.

- In Québec, federal income tax and EI are paid to the federal government; provincial income tax and QPP are paid to the provincial government.

- Personal income tax is usually based on the previous year’s income taxes and should be remitted in quarterly installments. An accountant may provide the architect with a schedule for remittances.

- Provincial sales tax (PST) is paid as supplies are purchased. Unless these supplies are sold again, PST is not collected or required to be collected by architectural practices, except in Québec where Quebec Sales Tax (QST) must be collected. PST is applicable in the provinces of British Columbia, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan.

- Corporate taxes, if the practice is incorporated, will be estimated by the accountant and should be remitted quarterly.

- Business taxes are charged by some municipalities for operating a business in their jurisdiction. [Note: In some municipalities, an architectural practice requires a business licence in order to provide services for a project located in that municipality, even though the practice is located elsewhere.]

[Note: The penalties for late payment are severe, and taxes should always be remitted on time.]

Software

Accounting and time-counting software and apps are useful tools to help organize, record and access financial information. Examples of accounting and time-counting software commonly used in the industry include:

Accounting (and Project Management)

- Deltek Vision

- Deltek Ajera

- Clearview

Time-counting

- Harvest

- Journyx

- Tsheets

Table 6: Sample Cashflow Forecast

References

Dauderis, Henry, David Annand, and Lyryx Learning. Introduction to Financial Accounting. Athabasca University, ed., Creative Commons License, 2019.

Getz, Lowell. Financial Management for the Design Professional. New York, NY: Whitney Library of Design, 1984.

Getz, Lowell. An Architect’s Guide to Financial Management. Washington, D.C.: The American Institute of Architects Press, 1997.

Stasiowski, Frank A. Dollars & Sense — PSMJ’s Guide to Financial Management. Newton, MA: PSMJ Resources, Inc., 1997.

Stone, David A. Mastering the Business of Architecture. (Ontario title only.) Toronto, ON: Ontario Association of Architects, 1999.

Stone, David. Mastering the Business of Design. Impact Initiatives, 1999. (Outside of Ontario)